To describe the magnitude and characteristics of crashes and drivers involved in head-on crashes on two-way interurban roads in Spain between 2007 and 2012, and to identify the factors associated with the likelihood of head-on crashes on these roads compared with other types of crash.

MethodsA cross-sectional study was conducted using the National Crash Register. The dependent variables were head-on crashes with injury (yes/no) and drivers involved in head-on crashes (yes/no). Factors associated with head-on crashes and with being a driver involved in a head-on crash versus other types of crash were studied using a multivariate robust Poisson regression model to estimate proportion ratios (PR) and confidence intervals (95% CI).

ResultsThere were 9,192 head-on crashes on two-way Spanish interurban roads. A total of 15,412 men and 3,862 women drivers were involved. Compared with other types of crash, head-on collisions were more likely on roads 7 m or more wide, on road sections with curves, narrowings or drop changes, on wet or snowy surfaces, and in twilight conditions. Transgressions committed by drivers involved in head-on crashes were driving in the opposite direction and incorrectly overtaking another vehicle. Factors associated with a lower probability of head-on crashes were the existence of medians (PR=0.57; 95%CI: 0.48-0.68) and a paved shoulder of less than 1.5 meters (PR=0.81; 95%CI: 0.77-0.86) or from 1.5 to 2.45 meters (PR=0.90; 95%CI: 0.84-0.96).

ConclusionsThis study allowed the characterization of crashes and drivers involved in head-on crashes on two-way interurban roads. The lower probability observed on roads with median strips point to these measures as an effective way to reduce these collisions

Describir la magnitud y las características de las colisiones y de los conductores/as implicados/as en colisiones frontales en carretera convencional, e identificar los factores asociados a la probabilidad de colisión frontal respecto a otro tipo de colisiones, en España, en 2007-2012.

MétodosEstudio de diseño transversal utilizando el Registro de víctimas y accidentes. Las variables dependientes fueron la colisión frontal con víctimas (sí/no) y ser un conductor implicado en colisión frontal (sí/no). Se estudiaron los factores asociados a colisión o a ser un conductor implicado en colisión frontal respecto a los otros tipos de colisión, mediante un modelo multivariado de regresión de Poisson robusta, estimando razones de proporción (RP) y sus intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC95%).

ResultadosOcurrieron 9192 colisiones frontales en carretera convencional, con 15.412 hombres y 3862 mujeres involucrados/as. Hubo una mayor probabilidad de colisión frontal respecto a otro tipo de colisión en carreteras con 7 m o más de calzada, en curvas, estrechamiento de calzada o cambios de rasante, con superficie húmeda o nevada, y durante el crepúsculo. Conducir en dirección contraria y realizar un adelantamiento indebido se asocian a colisión frontal en conductores/as. La existencia de mediana (RP=0,57; IC95%: 0,48-0,68) o de arcén de menos de 1,5m (PR=0,81; IC95%: 0,77-0,86) o de 1,5m a 2,45m (PR=0,90; IC95%: 0,84-0,96) se asocian a menor probabilidad de colisión frontal.

ConclusionesEste estudio ha permitido caracterizar las colisiones y los conductores/as implicados en colisiones frontales en carretera convencional. La menor probabilidad de colisión frontal cuando existen medianas hace recomendable su implementación como medida efectiva para disminuir este tipo de colisiones.

A two-way interurban road is that outside urban areas, which does not meet the requirements for being considered a freeway or highway, and which usually has a single carriageway in each direction.1 These roads tend to have a worse design and are often not as well maintained as highways or trans-European road network roads.2 Although more than half of crashes in Europe occur on two-way interurban roads, little attention has been given to this problem. In Spain, these roads account for over 90% of overall road network kilometres, they are the ones with higher crash rates, even though traffic density is lower than on motorways. According to the National Traffic Authority (DGT), mortality on interurban roads has been reduced by 70% since year 2000; however, 1,230 people were still killed in 2013 in traffic crash on these roads, representing 73.2% of overall fatalities.3

Head-on crash and run-off the road are dominant in this type of roads, mainly due to manoeuvres like overtaking, or to factors such as speeding, driver distraction, poor road design, restricted visibility or obstacles in the edges.2 Some contributing factors to frequency or severity of head-on crashes reported are, maximum degree of horizontal and vertical curvature, shoulder width, side friction and increased percentage of light truck.4–6 Gårder reported driver contributing factors for head-on collisions such driver error or misjudgment, illegal or unsafe speed and inattention/distraction, fatigue and alcohol or drug use.7

The Community database on Accidents on the roads for Europe (CARE database) points that these crashes represent the most prevalent fatal crashes in most European countries, mainly due to head-on crashes.2 In Spain in 2013, according to DGT, there were 2,661 head-on injury crashes which accounted for 3.0% of all injury crashes and 222 fatalities involved in head-on crashes which represent 13.2% of all road fatalities (including urban and non-urban crashes).3 Due to the high severity rate, head-on crashes on these types of roads are a primary focus study area and one of the priority objectives of the 2011-2020 of the Spanish Road Safety Strategy.8 Therefore, the aims of this study are to describe the magnitude and the characteristics of crashes and drivers involved on head-on crashes occurred on two-way interurban roads in Spain between 2007 and 2012, and to identify the factors associated with a higher likelihood of head-on crashes on these roads compared to other type crash.

MethodsA cross-sectional design study was carried out using the Accidents and Victims Register of DGT. There are two study populations: 1) crashes, in which at least one person has been injured (injury crashes), occurred on two-way interurban roads in Spain; 2) the drivers involved in these injury crashes. The definition of interurban roads includes roads defined by the National Traffic Authority as secondary roads, secondary roads with slow lane and fast-tracks, with at least one lane in each direction and with a lane width equal to or greater than 3.25 meters.

The dependent variables were: 1) head-on injury crash (yes; no, include the other types of crashes); 2) drivers involved in an injury head-on crash (yes; no, include drivers involved in other types of crash), all occurred on two-way interurban roads and between 2007 and 2012. There can be more than two vehicles involved in a crash, and therefore more than two drivers.

Explanatory variables include variables related to the crash and to the driver. Crash related variables were: 1) variables on road characteristics, such as width of the road, intersections (crossing roads), road marks, paved shoulder, median separating lanes, safety barriers and delineator posts; 2) variables on the circumstances of the crash, such as involvement of a car, a motorcycle or moped, a bicycle, a bus and a truck or van, time and day, traffic density, illumination, atmospheric factors and surface conditions. Driver related variables used were: sex, age, vehicle type, years of experience driving (from the age of the driver's license), type of driver (professional or private), trip purpose (from the reason for travelling), number of occupants, use of safety measures (seat-belt, child restraint and helmet), driving without a license, any offence done by the driver, speed violation, alcohol or drug reporting.

Statistical analysisFirst, a descriptive analysis of head-on crashes was carried out using frequency distribution of road characteristics- and crash circumstances-related variables. Second, a descriptive analysis of the drivers involved on head-on crashes was carried out of driver characteristics and driver risk behaviour-related variables. Finally, crash-related factors associated to head-on crashes and, driver-related factors associated to be involved in a head-on crash, versus other type of crashes, were studied estimating Proportion Ratios (PR) and their 95% Confidence Intervals (95%CI). The most appropriate method to estimate PR would be Log- Binomial Regression method, however this model does not converge due to the presence of discrete explanatory variables with many categories. An alternative to estimate PR would be adjusted Robust Poisson regression models using generalized linear models (GLM) with a Poisson distribution and a log link. In addition, we used a robust method for estimating the variance of the errors, to avoid overestimation of this variance and obtain better estimates of PR.9,10 Models for men and women drivers were fitted separately.

The correlations between the explanatory variables were assessed using Spearman bivariate correlations and multicollinearity was analyzed by estimating the Variance Inflation Factor. We excluded from the final model traffic flow, post delineator and road markings because they have high multicollinearity with other variables of infrastructures such paved shoulder, medians and safety barriers. We removed also variables related to the cause of the crash, as some of them have more than 90% missing values and some of them refer to attitudes of the driver such alcohol or drug use, or inadequate speed, that were included in the models of drivers. Missing categories are included in the model in order to maintain statistical power, as some variables have a quite proportion of missing values. Only significant variables are shown in the final model.

ResultsHead-on crashes on interurban roadsBetween 2007 and 2012, 130,454 crashes occurred on Spanish two-way interurban roads, 7% of which were head-on crashes (n=9,192) in roads with a lane width equal to or greater than 3.25 meters. Two vehicles were involved in 90.6% of head-on crashes, 3 vehicles in 8% and between 4 and 8 in 1.4%. In 14.4% of head-on crashes there was a death and in 36.5% a severely injured, while in non head-on crashes these proportions were 3.5% and 16.6% respectively.

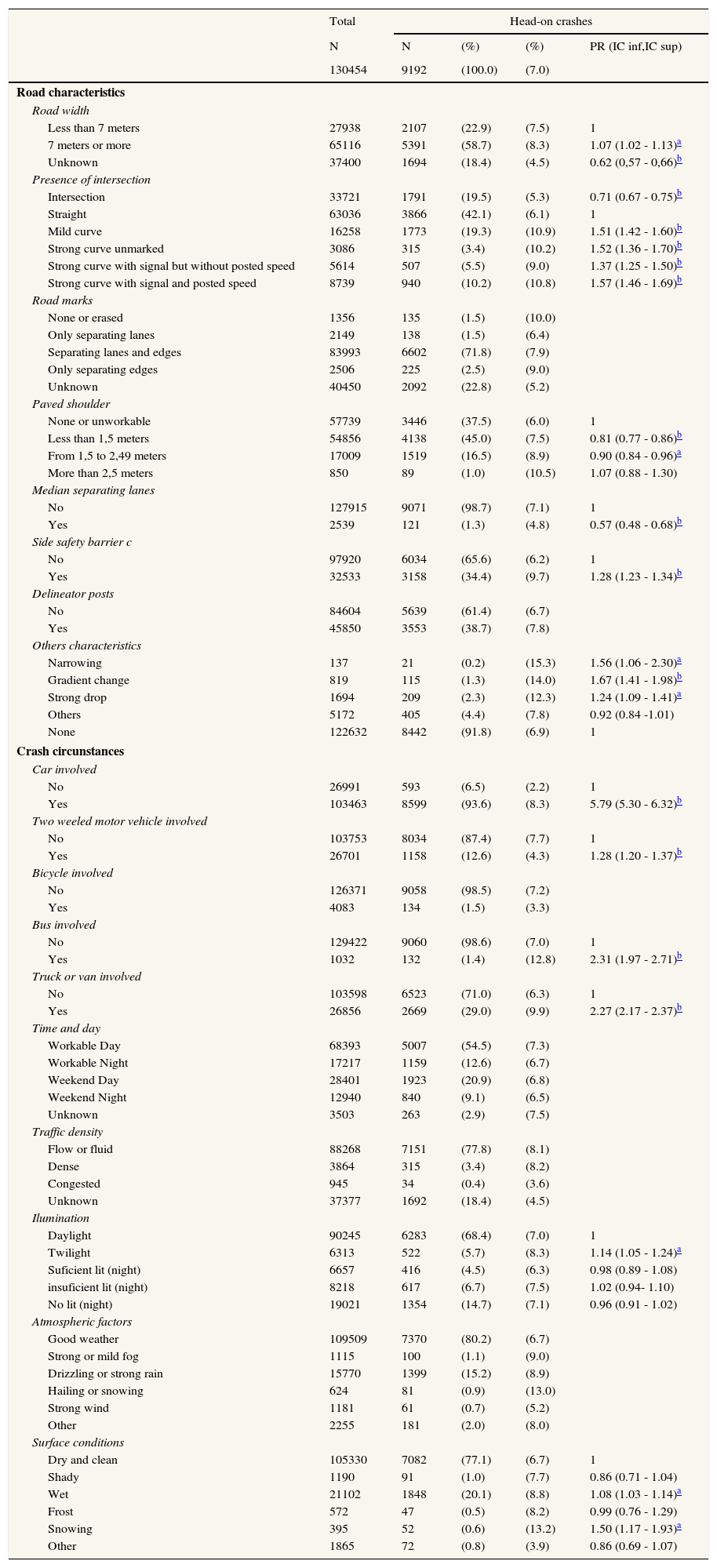

With regard to the road infrastructure, 58.7% of head-on crashes occurred in roads 7 meters wide or more, 42.1% occurred on a straight lane, 19.5% on an intersection, 19.3% on a smooth curve, and 10.2% on a strong curve with a speed signal (Table 1). 77.8% of head-on crashes occurred with fluid traffic density, 68.4% with daylight, 77.1% on a dry and clean surface, 80.2% with good weather conditions. In addition, 71.8% occurred on roads where road markings only defining lanes and edges, compared with 1.5% of crashes that occurred on roads where the marks were erased or nonexistent. Most head-on crashes occurred on roads without any medians (98.7%), safety barriers (65.6%), or delineator posts (61.4%). At least a car was involved in 93.6% of head-on crashes, a truck or a van in 29.0%, a motorcycle in 8.6% and a moped in 4.1% (Table 1).

Characteristics of total and head-on crashes according to road characteristics, and factors associated to head-on crashes compared to other types of crashes, on two-way interurban roads of Spain 2007-2012. Multivariate Poisson robust regression model. Prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| Total | Head-on crashes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | (%) | (%) | PR (IC inf,IC sup) | |

| 130454 | 9192 | (100.0) | (7.0) | ||

| Road characteristics | |||||

| Road width | |||||

| Less than 7 meters | 27938 | 2107 | (22.9) | (7.5) | 1 |

| 7 meters or more | 65116 | 5391 | (58.7) | (8.3) | 1.07 (1.02 - 1.13)a |

| Unknown | 37400 | 1694 | (18.4) | (4.5) | 0.62 (0,57 - 0,66)b |

| Presence of intersection | |||||

| Intersection | 33721 | 1791 | (19.5) | (5.3) | 0.71 (0.67 - 0.75)b |

| Straight | 63036 | 3866 | (42.1) | (6.1) | 1 |

| Mild curve | 16258 | 1773 | (19.3) | (10.9) | 1.51 (1.42 - 1.60)b |

| Strong curve unmarked | 3086 | 315 | (3.4) | (10.2) | 1.52 (1.36 - 1.70)b |

| Strong curve with signal but without posted speed | 5614 | 507 | (5.5) | (9.0) | 1.37 (1.25 - 1.50)b |

| Strong curve with signal and posted speed | 8739 | 940 | (10.2) | (10.8) | 1.57 (1.46 - 1.69)b |

| Road marks | |||||

| None or erased | 1356 | 135 | (1.5) | (10.0) | |

| Only separating lanes | 2149 | 138 | (1.5) | (6.4) | |

| Separating lanes and edges | 83993 | 6602 | (71.8) | (7.9) | |

| Only separating edges | 2506 | 225 | (2.5) | (9.0) | |

| Unknown | 40450 | 2092 | (22.8) | (5.2) | |

| Paved shoulder | |||||

| None or unworkable | 57739 | 3446 | (37.5) | (6.0) | 1 |

| Less than 1,5 meters | 54856 | 4138 | (45.0) | (7.5) | 0.81 (0.77 - 0.86)b |

| From 1,5 to 2,49 meters | 17009 | 1519 | (16.5) | (8.9) | 0.90 (0.84 - 0.96)a |

| More than 2,5 meters | 850 | 89 | (1.0) | (10.5) | 1.07 (0.88 - 1.30) |

| Median separating lanes | |||||

| No | 127915 | 9071 | (98.7) | (7.1) | 1 |

| Yes | 2539 | 121 | (1.3) | (4.8) | 0.57 (0.48 - 0.68)b |

| Side safety barrier c | |||||

| No | 97920 | 6034 | (65.6) | (6.2) | 1 |

| Yes | 32533 | 3158 | (34.4) | (9.7) | 1.28 (1.23 - 1.34)b |

| Delineator posts | |||||

| No | 84604 | 5639 | (61.4) | (6.7) | |

| Yes | 45850 | 3553 | (38.7) | (7.8) | |

| Others characteristics | |||||

| Narrowing | 137 | 21 | (0.2) | (15.3) | 1.56 (1.06 - 2.30)a |

| Gradient change | 819 | 115 | (1.3) | (14.0) | 1.67 (1.41 - 1.98)b |

| Strong drop | 1694 | 209 | (2.3) | (12.3) | 1.24 (1.09 - 1.41)a |

| Others | 5172 | 405 | (4.4) | (7.8) | 0.92 (0.84 -1.01) |

| None | 122632 | 8442 | (91.8) | (6.9) | 1 |

| Crash circunstances | |||||

| Car involved | |||||

| No | 26991 | 593 | (6.5) | (2.2) | 1 |

| Yes | 103463 | 8599 | (93.6) | (8.3) | 5.79 (5.30 - 6.32)b |

| Two weeled motor vehicle involved | |||||

| No | 103753 | 8034 | (87.4) | (7.7) | 1 |

| Yes | 26701 | 1158 | (12.6) | (4.3) | 1.28 (1.20 - 1.37)b |

| Bicycle involved | |||||

| No | 126371 | 9058 | (98.5) | (7.2) | |

| Yes | 4083 | 134 | (1.5) | (3.3) | |

| Bus involved | |||||

| No | 129422 | 9060 | (98.6) | (7.0) | 1 |

| Yes | 1032 | 132 | (1.4) | (12.8) | 2.31 (1.97 - 2.71)b |

| Truck or van involved | |||||

| No | 103598 | 6523 | (71.0) | (6.3) | 1 |

| Yes | 26856 | 2669 | (29.0) | (9.9) | 2.27 (2.17 - 2.37)b |

| Time and day | |||||

| Workable Day | 68393 | 5007 | (54.5) | (7.3) | |

| Workable Night | 17217 | 1159 | (12.6) | (6.7) | |

| Weekend Day | 28401 | 1923 | (20.9) | (6.8) | |

| Weekend Night | 12940 | 840 | (9.1) | (6.5) | |

| Unknown | 3503 | 263 | (2.9) | (7.5) | |

| Traffic density | |||||

| Flow or fluid | 88268 | 7151 | (77.8) | (8.1) | |

| Dense | 3864 | 315 | (3.4) | (8.2) | |

| Congested | 945 | 34 | (0.4) | (3.6) | |

| Unknown | 37377 | 1692 | (18.4) | (4.5) | |

| Ilumination | |||||

| Daylight | 90245 | 6283 | (68.4) | (7.0) | 1 |

| Twilight | 6313 | 522 | (5.7) | (8.3) | 1.14 (1.05 - 1.24)a |

| Suficient lit (night) | 6657 | 416 | (4.5) | (6.3) | 0.98 (0.89 - 1.08) |

| insuficient lit (night) | 8218 | 617 | (6.7) | (7.5) | 1.02 (0.94- 1.10) |

| No lit (night) | 19021 | 1354 | (14.7) | (7.1) | 0.96 (0.91 - 1.02) |

| Atmospheric factors | |||||

| Good weather | 109509 | 7370 | (80.2) | (6.7) | |

| Strong or mild fog | 1115 | 100 | (1.1) | (9.0) | |

| Drizzling or strong rain | 15770 | 1399 | (15.2) | (8.9) | |

| Hailing or snowing | 624 | 81 | (0.9) | (13.0) | |

| Strong wind | 1181 | 61 | (0.7) | (5.2) | |

| Other | 2255 | 181 | (2.0) | (8.0) | |

| Surface conditions | |||||

| Dry and clean | 105330 | 7082 | (77.1) | (6.7) | 1 |

| Shady | 1190 | 91 | (1.0) | (7.7) | 0.86 (0.71 - 1.04) |

| Wet | 21102 | 1848 | (20.1) | (8.8) | 1.08 (1.03 - 1.14)a |

| Frost | 572 | 47 | (0.5) | (8.2) | 0.99 (0.76 - 1.29) |

| Snowing | 395 | 52 | (0.6) | (13.2) | 1.50 (1.17 - 1.93)a |

| Other | 1865 | 72 | (0.8) | (3.9) | 0.86 (0.69 - 1.07) |

Multivariate analysis showed road characteristics related factors associated with a greater likelihood of a head-on crash with respect to the other types of crash: a road width of 7 meters or more (PR=1.07 [1.02-1.13]) versus lanes of 6.50-6.99m; any type of curve instead straight lane, either a soft curve, a marked non-signposted curve, a marked signposted curve but without a speed signpost or a marked signposted curve with a speed signpost; the presence of side safety barrier on the road (PR=1.28 [1.23-1.34]); the presence of a road narrowing (PR=1.56 [1.06-2.30]), a gradient change (PR=1.67 [1.41-1.98]) or a strong drop (PR=1.24 [1.09-1.41]). Crash circumstances related factors are: involvement of a car (PR=5.79 [5.30-6.32]), a two wheeled motor vehicle (PR=1.28 [1.20-1.37]), a bus (PR=2.31 [1.97-2.71]), and a truck or van (PR=2.27 [2.17-2.37]); twilight instead of daylight (PR=1.14 [1.05-1.24]); a wet (PR=1.08 [1.03-1.14]) or snowy surface (PR=1.50 [1.17-1.93]) instead of a dry and clean one (Table 1).

On the contrary, road characteristics related factors associated with a lower likelihood of head-on crash with respect to the other types of crash are: the presence of an intersection (PR=0.71 [0.67-0.75]) instead straight lane; presence of a paved shoulder of less than 1.5 meters (PR=0.81[0.77-0.86]) or 1.5 to 2.49 meters (PR=0.90 [0.84-0.96]); and the presence of a median (PR=0.57 [0.48-0.68]) (Table 1).

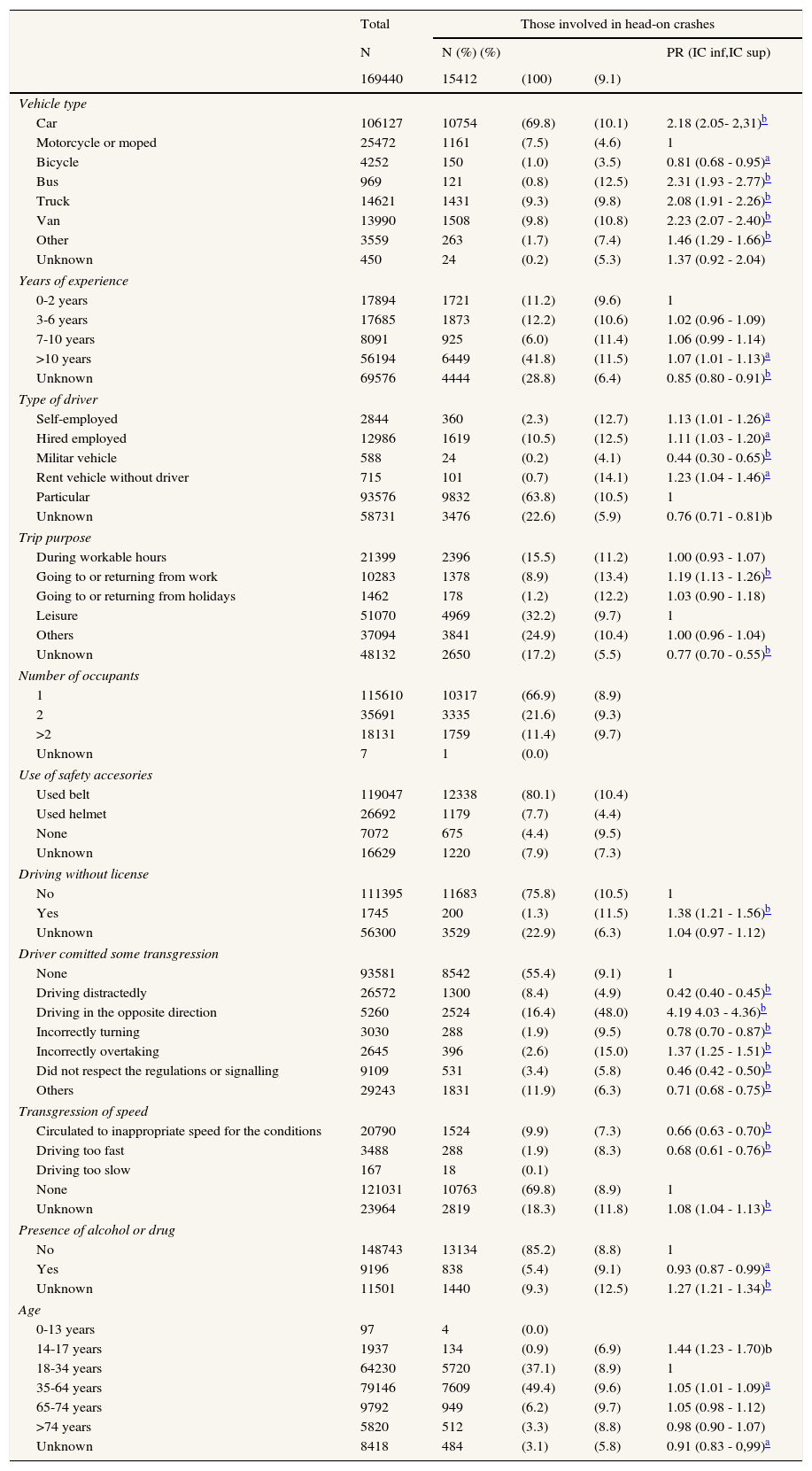

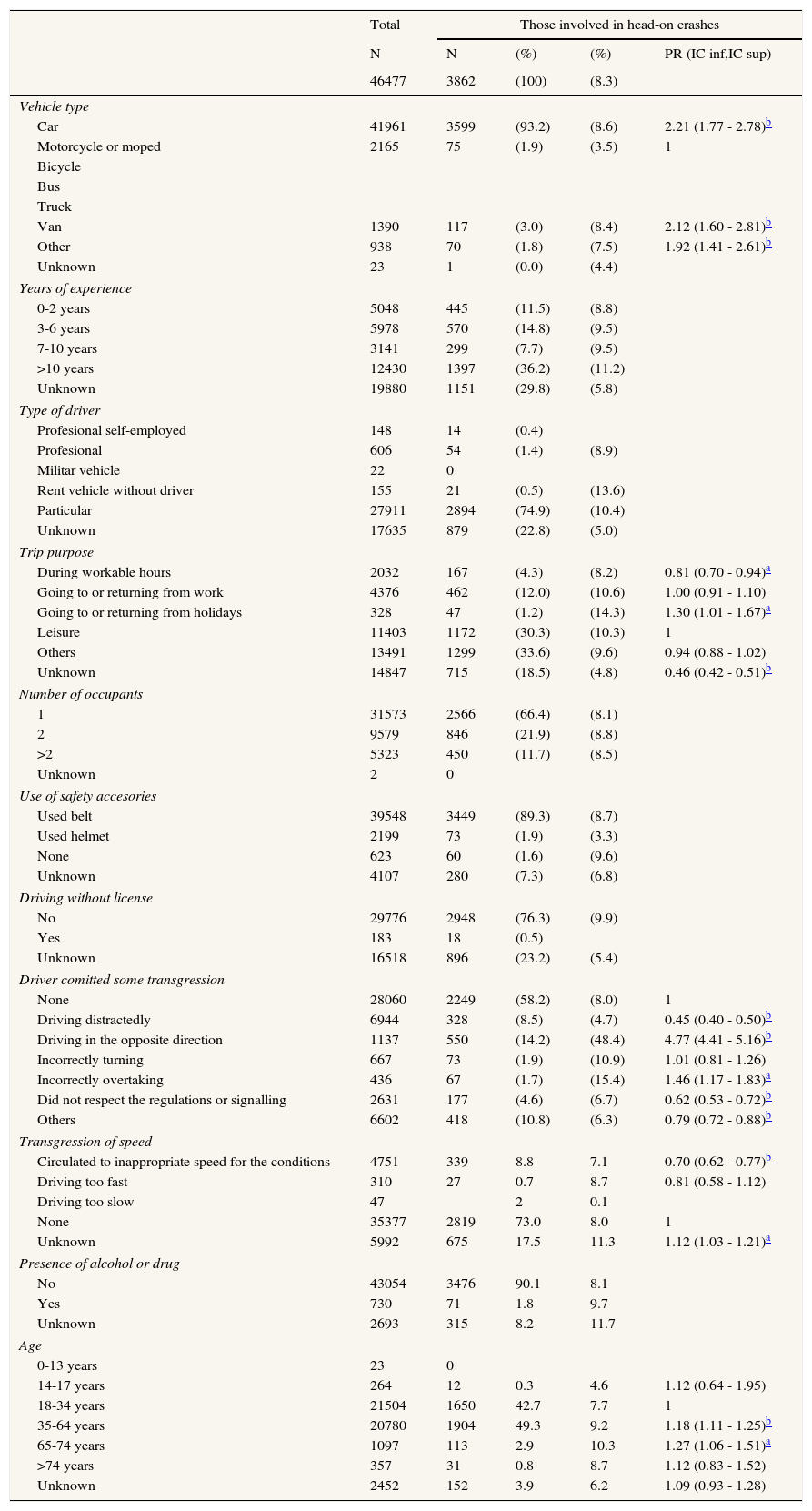

Drivers involved in a head-on crash on interurban roadsBetween 2007 and 2012, 169,440 men and 46,477 women drivers were involved in a crash on two-way interurban roads with a lane width equal to or greater than 3.25 meters in Spain, 9.1% and 8.3% of which, respectively, in head-on crashes. Half of drivers involved in a head-on crash were aged 35 to 64 years old in both sexes, and 37.1% of men and 42.7% of women drivers were 18-34 years old. 69.8% of men drivers involved were car drivers while 9.8% and 9.3% were van or truck drivers, respectively. Among women, more than 90% were car drivers while only 3.0% were van drivers (Tables 2 and 3).

Characteristics of men drivers involved in head-on crashes and factors associated to be a driver involved in a head-on crash compared to other types of crashes on two-way interurban roads of Spain in 2007-2012. Multivariate Poisson robust regression model. Proportion ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| Total | Those involved in head-on crashes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) (%) | PR (IC inf,IC sup) | |||

| 169440 | 15412 | (100) | (9.1) | ||

| Vehicle type | |||||

| Car | 106127 | 10754 | (69.8) | (10.1) | 2.18 (2.05- 2,31)b |

| Motorcycle or moped | 25472 | 1161 | (7.5) | (4.6) | 1 |

| Bicycle | 4252 | 150 | (1.0) | (3.5) | 0.81 (0.68 - 0.95)a |

| Bus | 969 | 121 | (0.8) | (12.5) | 2.31 (1.93 - 2.77)b |

| Truck | 14621 | 1431 | (9.3) | (9.8) | 2.08 (1.91 - 2.26)b |

| Van | 13990 | 1508 | (9.8) | (10.8) | 2.23 (2.07 - 2.40)b |

| Other | 3559 | 263 | (1.7) | (7.4) | 1.46 (1.29 - 1.66)b |

| Unknown | 450 | 24 | (0.2) | (5.3) | 1.37 (0.92 - 2.04) |

| Years of experience | |||||

| 0-2 years | 17894 | 1721 | (11.2) | (9.6) | 1 |

| 3-6 years | 17685 | 1873 | (12.2) | (10.6) | 1.02 (0.96 - 1.09) |

| 7-10 years | 8091 | 925 | (6.0) | (11.4) | 1.06 (0.99 - 1.14) |

| >10 years | 56194 | 6449 | (41.8) | (11.5) | 1.07 (1.01 - 1.13)a |

| Unknown | 69576 | 4444 | (28.8) | (6.4) | 0.85 (0.80 - 0.91)b |

| Type of driver | |||||

| Self-employed | 2844 | 360 | (2.3) | (12.7) | 1.13 (1.01 - 1.26)a |

| Hired employed | 12986 | 1619 | (10.5) | (12.5) | 1.11 (1.03 - 1.20)a |

| Militar vehicle | 588 | 24 | (0.2) | (4.1) | 0.44 (0.30 - 0.65)b |

| Rent vehicle without driver | 715 | 101 | (0.7) | (14.1) | 1.23 (1.04 - 1.46)a |

| Particular | 93576 | 9832 | (63.8) | (10.5) | 1 |

| Unknown | 58731 | 3476 | (22.6) | (5.9) | 0.76 (0.71 - 0.81)b |

| Trip purpose | |||||

| During workable hours | 21399 | 2396 | (15.5) | (11.2) | 1.00 (0.93 - 1.07) |

| Going to or returning from work | 10283 | 1378 | (8.9) | (13.4) | 1.19 (1.13 - 1.26)b |

| Going to or returning from holidays | 1462 | 178 | (1.2) | (12.2) | 1.03 (0.90 - 1.18) |

| Leisure | 51070 | 4969 | (32.2) | (9.7) | 1 |

| Others | 37094 | 3841 | (24.9) | (10.4) | 1.00 (0.96 - 1.04) |

| Unknown | 48132 | 2650 | (17.2) | (5.5) | 0.77 (0.70 - 0.55)b |

| Number of occupants | |||||

| 1 | 115610 | 10317 | (66.9) | (8.9) | |

| 2 | 35691 | 3335 | (21.6) | (9.3) | |

| >2 | 18131 | 1759 | (11.4) | (9.7) | |

| Unknown | 7 | 1 | (0.0) | ||

| Use of safety accesories | |||||

| Used belt | 119047 | 12338 | (80.1) | (10.4) | |

| Used helmet | 26692 | 1179 | (7.7) | (4.4) | |

| None | 7072 | 675 | (4.4) | (9.5) | |

| Unknown | 16629 | 1220 | (7.9) | (7.3) | |

| Driving without license | |||||

| No | 111395 | 11683 | (75.8) | (10.5) | 1 |

| Yes | 1745 | 200 | (1.3) | (11.5) | 1.38 (1.21 - 1.56)b |

| Unknown | 56300 | 3529 | (22.9) | (6.3) | 1.04 (0.97 - 1.12) |

| Driver comitted some transgression | |||||

| None | 93581 | 8542 | (55.4) | (9.1) | 1 |

| Driving distractedly | 26572 | 1300 | (8.4) | (4.9) | 0.42 (0.40 - 0.45)b |

| Driving in the opposite direction | 5260 | 2524 | (16.4) | (48.0) | 4.19 4.03 - 4.36)b |

| Incorrectly turning | 3030 | 288 | (1.9) | (9.5) | 0.78 (0.70 - 0.87)b |

| Incorrectly overtaking | 2645 | 396 | (2.6) | (15.0) | 1.37 (1.25 - 1.51)b |

| Did not respect the regulations or signalling | 9109 | 531 | (3.4) | (5.8) | 0.46 (0.42 - 0.50)b |

| Others | 29243 | 1831 | (11.9) | (6.3) | 0.71 (0.68 - 0.75)b |

| Transgression of speed | |||||

| Circulated to inappropriate speed for the conditions | 20790 | 1524 | (9.9) | (7.3) | 0.66 (0.63 - 0.70)b |

| Driving too fast | 3488 | 288 | (1.9) | (8.3) | 0.68 (0.61 - 0.76)b |

| Driving too slow | 167 | 18 | (0.1) | ||

| None | 121031 | 10763 | (69.8) | (8.9) | 1 |

| Unknown | 23964 | 2819 | (18.3) | (11.8) | 1.08 (1.04 - 1.13)b |

| Presence of alcohol or drug | |||||

| No | 148743 | 13134 | (85.2) | (8.8) | 1 |

| Yes | 9196 | 838 | (5.4) | (9.1) | 0.93 (0.87 - 0.99)a |

| Unknown | 11501 | 1440 | (9.3) | (12.5) | 1.27 (1.21 - 1.34)b |

| Age | |||||

| 0-13 years | 97 | 4 | (0.0) | ||

| 14-17 years | 1937 | 134 | (0.9) | (6.9) | 1.44 (1.23 - 1.70)b |

| 18-34 years | 64230 | 5720 | (37.1) | (8.9) | 1 |

| 35-64 years | 79146 | 7609 | (49.4) | (9.6) | 1.05 (1.01 - 1.09)a |

| 65-74 years | 9792 | 949 | (6.2) | (9.7) | 1.05 (0.98 - 1.12) |

| >74 years | 5820 | 512 | (3.3) | (8.8) | 0.98 (0.90 - 1.07) |

| Unknown | 8418 | 484 | (3.1) | (5.8) | 0.91 (0.83 - 0,99)a |

Characteristics of women drivers involved in head-on crashes and factors associated to be a driver involved in a head-on crash compared to other types of crashes on two-way interurban roads of Spain in 2007-2012. Multivariate Poisson robust regression model. Proportion ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

| Total | Those involved in head-on crashes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | (%) | (%) | PR (IC inf,IC sup) | |

| 46477 | 3862 | (100) | (8.3) | ||

| Vehicle type | |||||

| Car | 41961 | 3599 | (93.2) | (8.6) | 2.21 (1.77 - 2.78)b |

| Motorcycle or moped | 2165 | 75 | (1.9) | (3.5) | 1 |

| Bicycle | |||||

| Bus | |||||

| Truck | |||||

| Van | 1390 | 117 | (3.0) | (8.4) | 2.12 (1.60 - 2.81)b |

| Other | 938 | 70 | (1.8) | (7.5) | 1.92 (1.41 - 2.61)b |

| Unknown | 23 | 1 | (0.0) | (4.4) | |

| Years of experience | |||||

| 0-2 years | 5048 | 445 | (11.5) | (8.8) | |

| 3-6 years | 5978 | 570 | (14.8) | (9.5) | |

| 7-10 years | 3141 | 299 | (7.7) | (9.5) | |

| >10 years | 12430 | 1397 | (36.2) | (11.2) | |

| Unknown | 19880 | 1151 | (29.8) | (5.8) | |

| Type of driver | |||||

| Profesional self-employed | 148 | 14 | (0.4) | ||

| Profesional | 606 | 54 | (1.4) | (8.9) | |

| Militar vehicle | 22 | 0 | |||

| Rent vehicle without driver | 155 | 21 | (0.5) | (13.6) | |

| Particular | 27911 | 2894 | (74.9) | (10.4) | |

| Unknown | 17635 | 879 | (22.8) | (5.0) | |

| Trip purpose | |||||

| During workable hours | 2032 | 167 | (4.3) | (8.2) | 0.81 (0.70 - 0.94)a |

| Going to or returning from work | 4376 | 462 | (12.0) | (10.6) | 1.00 (0.91 - 1.10) |

| Going to or returning from holidays | 328 | 47 | (1.2) | (14.3) | 1.30 (1.01 - 1.67)a |

| Leisure | 11403 | 1172 | (30.3) | (10.3) | 1 |

| Others | 13491 | 1299 | (33.6) | (9.6) | 0.94 (0.88 - 1.02) |

| Unknown | 14847 | 715 | (18.5) | (4.8) | 0.46 (0.42 - 0.51)b |

| Number of occupants | |||||

| 1 | 31573 | 2566 | (66.4) | (8.1) | |

| 2 | 9579 | 846 | (21.9) | (8.8) | |

| >2 | 5323 | 450 | (11.7) | (8.5) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 0 | |||

| Use of safety accesories | |||||

| Used belt | 39548 | 3449 | (89.3) | (8.7) | |

| Used helmet | 2199 | 73 | (1.9) | (3.3) | |

| None | 623 | 60 | (1.6) | (9.6) | |

| Unknown | 4107 | 280 | (7.3) | (6.8) | |

| Driving without license | |||||

| No | 29776 | 2948 | (76.3) | (9.9) | |

| Yes | 183 | 18 | (0.5) | ||

| Unknown | 16518 | 896 | (23.2) | (5.4) | |

| Driver comitted some transgression | |||||

| None | 28060 | 2249 | (58.2) | (8.0) | 1 |

| Driving distractedly | 6944 | 328 | (8.5) | (4.7) | 0.45 (0.40 - 0.50)b |

| Driving in the opposite direction | 1137 | 550 | (14.2) | (48.4) | 4.77 (4.41 - 5.16)b |

| Incorrectly turning | 667 | 73 | (1.9) | (10.9) | 1.01 (0.81 - 1.26) |

| Incorrectly overtaking | 436 | 67 | (1.7) | (15.4) | 1.46 (1.17 - 1.83)a |

| Did not respect the regulations or signalling | 2631 | 177 | (4.6) | (6.7) | 0.62 (0.53 - 0.72)b |

| Others | 6602 | 418 | (10.8) | (6.3) | 0.79 (0.72 - 0.88)b |

| Transgression of speed | |||||

| Circulated to inappropriate speed for the conditions | 4751 | 339 | 8.8 | 7.1 | 0.70 (0.62 - 0.77)b |

| Driving too fast | 310 | 27 | 0.7 | 8.7 | 0.81 (0.58 - 1.12) |

| Driving too slow | 47 | 2 | 0.1 | ||

| None | 35377 | 2819 | 73.0 | 8.0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 5992 | 675 | 17.5 | 11.3 | 1.12 (1.03 - 1.21)a |

| Presence of alcohol or drug | |||||

| No | 43054 | 3476 | 90.1 | 8.1 | |

| Yes | 730 | 71 | 1.8 | 9.7 | |

| Unknown | 2693 | 315 | 8.2 | 11.7 | |

| Age | |||||

| 0-13 years | 23 | 0 | |||

| 14-17 years | 264 | 12 | 0.3 | 4.6 | 1.12 (0.64 - 1.95) |

| 18-34 years | 21504 | 1650 | 42.7 | 7.7 | 1 |

| 35-64 years | 20780 | 1904 | 49.3 | 9.2 | 1.18 (1.11 - 1.25)b |

| 65-74 years | 1097 | 113 | 2.9 | 10.3 | 1.27 (1.06 - 1.51)a |

| >74 years | 357 | 31 | 0.8 | 8.7 | 1.12 (0.83 - 1.52) |

| Unknown | 2452 | 152 | 3.9 | 6.2 | 1.09 (0.93 - 1.28) |

The multivariate analysis shows that drivers factors associated to a greater likelihood of being involved in a head-on crash on interurban roads with respect to the other types of crash were: among men, car, bus, truck or van compared to two-wheeled motor vehicles riders, being a self-employed (PR=1.13 [1.01-1.26]) or hired-employed (PR=1.11 [1.03-1.20]) instead of particular driver and going to or returning from work (PR=1.19 [1.13-1.26]) (Table 2); among women, car or van driver compared to two-wheeled motor vehicle riders (Table 3).

Driver behaviours associated with a greater likelihood of head-on crash compared to the other types of crash are driving in the opposite direction (for men PR=4.19 [4.03-4.36] and for women PR=4.77 [4.41-5.16]) and incorrectly overtaking (PR=1.37 [1.25-1.51] and PR=1.46 [1.17-1.83], respectively) compared to those who did not commit any transgression (Tables 2 and 3); and only among men, having more than 10 years of driver license PR=1.07 [1.01-1.13] (Table 2).

In both men and women drivers factors associated with a lower likelihood of head-on crashes with respect to the other types of crash are offenses such as driving distractedly, not respecting the regulations or signalling, or driving too fast or at an inappropriate speed for the road conditions, compared to not committed any offence; Incorrectly turning and having consumed alcohol or drugs among men, and driving during workable hours in women are also associated with a lower likelihood of head-on crashes (Tables 2 and 3).

DiscussionMain resultsThis paper shows, as far as the authors know, for the first time an analysis of head-on crashes on two-way interurban roads in Spain, including national data. Factors related to road infrastructure such as roads of 7 meters width or more and the presence of curves, slope changes, road narrowing, a side safety barrier, twilight, wet and snowy surface conditions were identified as characteristics with higher probability of head-on crashes comparing to other type of crashes. On the other hand, when there are medians to separate opposite lanes, intersections and paved shoulder there is a lower likelihood of head-on crashes with respect to the other types of crash. Men driver patterns, driving in the opposite direction or incorrectly overtaking, employed, going to or returning from work were associated with an increased probability of head-on crashes compared to the other crashes. Women driver patterns, during working hours, driving in the opposite direction or incorrectly overtaking were associated with a higher likelihood of head-on crashes.

Strengths and limitationsThe major strength of the study is that due to the availability of a comprehensive database from the National Traffic Authority for six years, which includes an important number of crashes occurred at national level. It allowed studying not only factors related to the environment and conditions of the crash but also those related to the drivers involved.

However it must be highlighted as a limitation that the design of the study allows knowing the factors associated to head-on crash compared to factors associated to other types of crashes. There could be some factors associated to head-on crashes that are not seen because they are associate as well with other types of crashes. However the results observed are consistent with the literature. It has not been possible to identify factors related to head-on crashes comparing with no crashes because there is no available data when there is no crash. In any way, this design is commonly used to study disease mortality patterns by cause in settings where population denominators are not available.10

Comparison with other studiesRegarding road infrastructure, our results coincide with others in the literature revealing that the presence of curves, whether soft or marked, the narrowing of the road, slope changes and side barriers are factors associated with an increased risk of head-on crashes.2,6 On the other hand, the existence of paved shoulders, and intersections reduces the likelihood of head-on crashes with respect to the other types of crash. Some authors found that paved shoulders and intersections are factors that contribute to a lower number of head-on collisions, but on the other side are factors associated to higher severity.6,7

Matena et al.2 reported that slippery roads due to rain or winter time are related to head-on crashes. Our study confirms this relationship, as a wet or snowy surface has been associated with head-on crashes compared to other type of crashes. In addition, driving during twilight was identified as a factor associated with an increased risk for head-on crashes. This could be due to the decreased visibility at that hour of the day, when factors related to an increased likelihood of a head-on impact such as glare from the sun or presence of fog may be present.11

Regarding driver related factors, several studies have associated head-on crashes to factors such as inattention of drivers resulting from fatigue or drowsiness, or inappropriate speed, especially on road stretches with curves, and alcohol or drug use.2,7 In our study, crashes caused by distraction or inappropriate speed occurred in almost half of head-on crashes; however, they are associated with a lower probability of head-on crash comparing to other types of crash. We found other counterintuitive results such lower risk of head-on crash if not respecting regulations or use of alcohol. This may be due to the fact that those studies analyzed factors related to head-on crashes, regardless of factors related to other types of crash. The fact that some tracks favour quick driving or distraction is a factor related to any type of crash and not specifically to head-on crashes. On the other hand incorrectly overtaking or driving in the inappropriate direction are obvious factors specifically related to head-on crash.

It must be highlighted that only among men drivers, being a professional driver and travelling to and from work are factors related to an increased probability of head-on crashes compared to other types of crashes. Shariat-Mohaym et al. reported a conflicts of head-on crashes occurred more often on workdays than on holidays.5 In Spain according to a report from DGT,12 men were injured three times more likely than women going to and from work, and twelve deaths of men occurred for each of the women in crashes in the normal working day. This points to men workers as a work related crashes risk group, and could be due to the different occupational exposure by gender, being men those who are more likely to work in transportation sector. This is also coherent with our results in the sense that only among men being a bus or truck driver is a factor associated to head-on crashes.

Finally, our results showed a lower likelihood of head-on crash when there is a median. This reinforces that implementing systems to separate lanes in two-way interurban roads could avoid severe crashes such are the head-on. A number of studies in other countries have demonstrated the effectiveness of the installation of measures of central separation between opposing lanes: the installation of rumble strips between opposite lanes of rural roads has been associated with a 25% reduction of frontal crashes,13 the installation of flexible barriers (cable type) has been associated with a 56% reduction of head-on crashes with serious injuries14 and installing concrete medians, guardrails or raised medians has been linked to a reduction of overall crashes15,16 and specifically to head-on crashes.17,18 As recommended by Hosseinpour et al.6 the installation of centreline median barriers on undivided roadways seems to be the most effective counter-measure; however, due to the great expenses associated with the installation and maintenance of continuous median barriers, for lower risk locations, centreline rumble strips could be effectively installed to reduce crossover collisions.

Conclusions and implicationsThis paper has allowed characterizing head-on crashes and drivers involved in these crashes in Spain, and to identify factors associated with a higher likelihood or head-on crashes comparing to other types of crashes. Environmental factors such as roads of 7 meters width or more, the presence of curves, slope changes, road narrowing, a side safety barrier, twilight, wet and snowy surface conditions were identified as characteristics with higher probability of head-on crashes comparing to other type of crashes. Driver patterns, such driving in the opposite direction or incorrectly overtaking, employed, going to or returning from work among men were associated with a higher likelihood of head-on crashes. The existence of medians to separate lanes has been pointed as being significantly associated with lower probability of head-on crashes. It is necessary to implement adapted systems to these small roads, different from highways, to separate lanes in two-way interurban roads that could avoid severe crashes such are the head-on.

More than half of crashes in Europe occur on two-way interurban roads, of which head-on crashes are the most severe. Central two-way separation systems are effective measures for reducing head-on crashes. Due to their high severity, head-on crashes are a primary focus for research.

What does this study add to the literature?This study identifies crash-related factors (bends, slopes, road narrowing, and side safety barriers) and driver-related factors (driving in the opposite direction, performing incorrect overtaking manoeuvres, being employed, men travelling to or from work) that were associated with greater risk of head-on crashes on two-lane interurban roads, compared to other types of crash.

Miguel Ángel Negrín Hernández.

Authorship contributionsK. Pérez, M. Olabarria and E. Santamariña-Rubio conceived the study and performed the analysis. M. Olabarria wrote the draft. K. Pérez, E. Santamariña-Rubio, M. Olabarria, M. Marí-Dell’Olmo, M. Gotsens, A.M. Novoa and C. Borrell contributed substantially to the interpretation of the data, revised critically the draft and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis work is part of the project “Semi-separación de calzadas en carretera convencional: análisis de diferentes sistemas y evaluación de intervenciones ya realizadas” (Núm. Expediente: 0100DGT22160). The results of this study are owned by the National Traffic Authority (DGT).

Conflicts of interestOne of the authors (C. Borrell) belongs to the Gaceta Sanitaria editorial committee, but was not involved in the editorial process of the manuscript.