The July 2022 issue of the journal Lancet Infectious Disease1 reported on the 25-panel exhibit “Vaccines and Voyages” of the Edinburgh Science Festival. A major theme of the exhibit was the Royal Philanthropic Expedition to transport the smallpox vaccine by Francisco Xavier Balmis.2 Increasing awareness of the public of the first international vaccination campaign in the history of public health is a laudable effort.3 We were, however, surprised by the report and the actual exhibit of the many of the panels of this exhibit that contained implicit and ubiquitous links of the Balmis's Expedition with the Atlantic slave trade (https://www.iash.ed.ac.uk/event/vaccine-voyages). The last panel accurately cites references that confirm the lack of association of the Expedition with slavery.3,4 The misinformation reported in this article contains multiple assumptions and inaccuracies from the exhibit (Fig. 1).

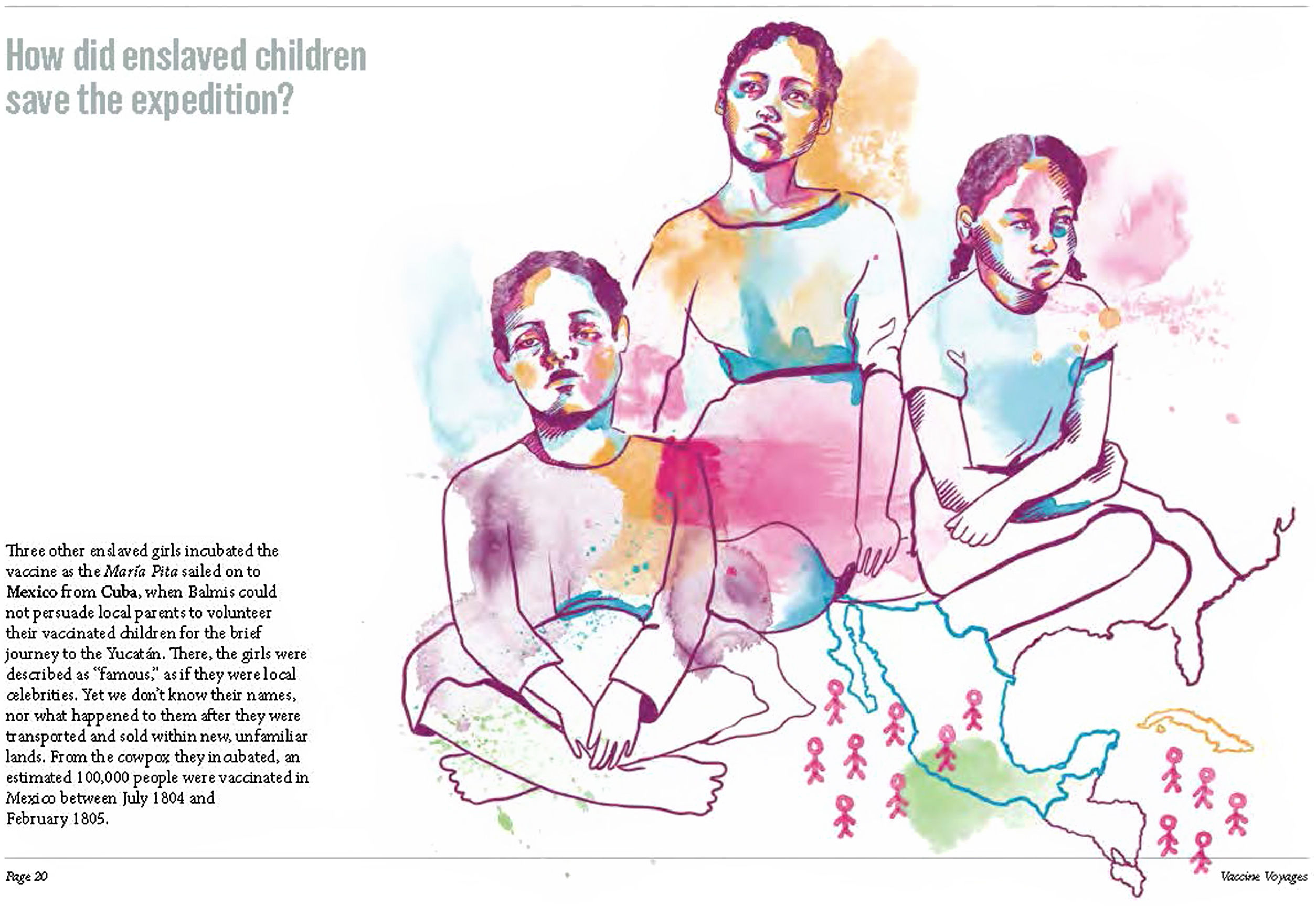

The Expedition was never designed to inflict any abuse or to humiliate the children. Although Balmis was a controversial figure, he consistently manifested concern for the fate of the 22 orphan children that he transported when he departed from La Coruña to Mexico, as well as for the 26 Mexican children who, in turn, transported the vaccine from Acapulco to the Philippines.5 Contrary to what the panels show, the Expedition spanned a 10-year period, from 1803 to 1813, including Balmis’ second trip to Mexico.3,5 This second journey stemmed from his interest in learning of the fate of all children of the Expeditions, among whom there were neither girls nor slaves.2–5 Historical records obtained from the National Historical Mexican Archive provide crucial information regarding the fate of these children: some were adopted by devoted families, while others were raised in the famous Patriotic School.4 The most relevant and comprehensive document on the Expedition (file 1558) is kept in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain. Among its 1560 folios, the word “slave” appears only six times, either to register a vaccinated child or in one single quote, “we bought four slaves to transport the vaccine from Havana to Yucatan”. This single case does not justify panel 24 of the exhibit assertion: “Millions of people were saved from a gruesome and painful death by the work of Balmis’ team but more importantly by the many enslaved and orphaned children he exploited”.

Neither Balmis's Expedition nor Jenner's work would be approved by current ethical standards of research. Nevertheless, while some members of the Expedition seldomly employed slaves as carriers of the vaccine, the exhibit and the report distract the audience from the true legacy of the Expedition. The Expedition was a colossal sanitary planning project with a tangible legacy in global health. In addition to introducing the smallpox vaccine to protect populations, it contributed to the professionalization of public health and began an era of technology transfer.3 Should we then assume that Jenner was wrong when he said of the Expedition: “I cannot imagine that in the annals of history there is a more noble and comprehensive example of philanthropy than this”? We chose to side with Jenner's view.

Authorship contributionsThe authors have contributed equally to the writing of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.