To explore Southern European immigrant mothers and fathers’ experiences of reproductive health services in Norway, and their perceptions of health providers’ beliefs and attitudes regarding pregnancy and childbirth.

MethodWe employed a qualitative research methodology with two focus group discussions and 11 in-depth interviews with 4 fathers and 11 mothers from Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, whose children were born in Norway. Thematic Analysis was conducted to identify and analyze patterns across the data.

ResultsWe identified three themes as key elements in parents’ experiences: experiences with the coverage and organization of the Reproductive Health Services; relational experiences with health providers; and pregnancy and delivery as a culturally-shaped event. The immigrant parents experienced a clash between their expectations and the procedures and health facility environment encountered in Norway regarding check-ups, diagnosis tests, childbirth preparation courses, and health facilities. Informants perceived that the maternity care practices of the host country were underpinned by the health care providers’ cultural understandings of labor and pregnancy. Particularly, they experienced a less interventionist approach towards pregnancy and childbirth.

ConclusionsThe experiences of immigrant parents provide relevant information to improve reproductive health services in a cross-cultural context. Inmigration brings new challenges that must be addressed from a perspective of cultural competence. These services should acknowledge diversity in cultural beliefs around childrearing and involve both fathers and mothers in decision-making.

Explorar cómo fueron las experiencias de padres y madres inmigrantes procedentes del sur de Europa al utilizar los servicios de salud reproductiva en Noruega, así como sus percepciones sobre las actitudes y las creencias del personal de salud con respecto al embarazo y el parto.

MétodoEstudio cualitativo, basado en dos grupos focales y 11 entrevistas en profundidad con 4 padres y 11 madres italianos, españoles, portugueses y griegos, quienes habían tenido algún/a hijo/a en Noruega. Los datos se analizaron usando análisis temático.

ResultadosEmergieron tres temas: experiencias con la cobertura y la organización de los servicios de salud reproductiva; experiencias con profesionales de salud; y embarazo y parto como eventos culturales. Los padres y las madres inmigrantes experimentaron un choque entre sus expectativas y las prácticas de los servicios de salud reproductiva noruegos, especialmente en cuanto a consultas, procedimientos, pruebas diagnósticas, preparación para el parto e infraestructura sanitaria. Los informantes percibieron que las prácticas de los/las profesionales de los servicios de salud reproductiva están influenciadas por creencias culturales relacionadas con el embarazo y el parto en Noruega. En concreto, los informantes experimentaron un enfoque menos intervencionista al recibir los cuidados perinatales del personal de salud en Noruega.

ConclusionesLas experiencias de los padres y las madres inmigrantes ofrecen información relevante para contribuir a mejorar los servicios de salud reproductiva en un contexto intercultural. La inmigración supone nuevos retos que deben afrontarse desde una perspectiva de competencia cultural. Los servicios de salud reproductiva deben reconocer la diversidad cultural en el embarazo y el parto, e involucrar a ambos progenitores.

Immigrant women are at risk of poorer maternal outcomes and inadequate prenatal care due to vulnerabilities associated with immigration like isolation, language barriers, and economic challenges.1,2 When immigrant women navigate reproductive health services (RHS) in a new country, they deal with cultural beliefs concerning pregnancy and childbirth that are different from those of their home countries and lack of information about the services.3 However, the risk of poor pregnancy outcomes is lower in countries with policies that offer immigrants new opportunities within the RHS.4

In Norway, the immigrant community has grown and now accounts for 14.7% of the population.5 Despite having declined significantly, immigrants’ fertility rate is higher than that of ethnic Norwegians, contributing to an increase of the total fertility rate.6 All pregnant women in Norway are entitled to free maternity care from the maternal and child health centers, which usually consist of eight antenatal appointments and an ultrasound between weeks 17-19. Birth preparation courses are arranged by maternal and child health centers or hospitals with local variations. Some municipalities offer free courses, whereas in others parents-to-be have to pay a course fee.

Few studies have explored immigrant women's experiences with the Norwegian RHS, most of which focus primarily on women from non-western countries, who have been found to have a greater risk of childbirth complications.7,8 The literature provides insight about the challenges of cross-cultural RHS in Norway, pointing at a lack of social support and knowledge about RHS as factors that reinforce immigrant women's insecurity about pregnancy and childbirth.1 These factors challenge also immigrant women's ability to assess the advice they receive from midwives, which reinforce unequal status between parties in the antenatal consultations.9

Although the Norwegian authorities have developed policies and protocols regarding antenatal and postnatal care to ensure equal access to healthcare,10–12 the Ministry of Health has stated that more knowledge is needed from immigrants’ perspectives about their experiences and expectations on RHS.13 Moreover, despite the positive outcomes of fathers’ involvement in RHS,14 research has neglected male experiences with RHS. Our study seeks to fill this gap by exploring the experiences of Southern European parents with the Norwegian RHS, and their perceptions of health providers’ beliefs and attitudes regarding pregnancy and childbirth.

MethodsStudy setting and sampleThis study is part of a project on the experiences of Spanish, Italian, Greek and Portuguese immigrant parents of raising their children and encountering welfare institutions in Norway.15 Southern Europe was hardly hit by the 2008-financial recession that triggered South-to-North intra-European migration.16 Spaniards comprise the largest Southern European group in Norway (6,211 people in 2018), followed by Italians (4,315), Portuguese (3,218) and Greeks (2,828).17

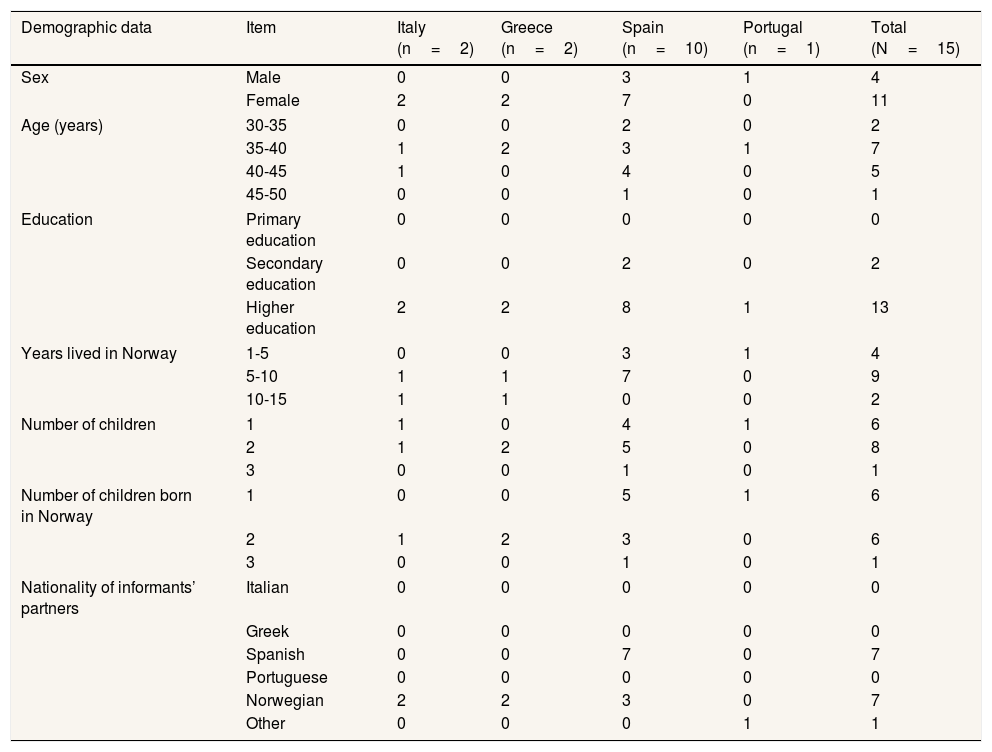

Informants were recruited through the first author's attendance to events organized by the Southern European communities in Norway, snowballing,18 and advertising in Facebook groups used by immigrants. The sample consisted of 15 Southern European parents (11 mothers and 4 fathers; 4 of which were married) who had experiences with the Norwegian prenatal care (n=15), and childbirth and postnatal care (n=13) (Table 1).

Data collection and analysisData were collected in Norway in 2017. Two focus group discussions (FGD) were conducted at a university setting in west Norway. One FGD was conducted in English with six mothers (two Italians, two Spaniards and two Greeks) who had lived in Norway for more than 5 years. The second FGD was conducted in Spanish with four Spanish mothers who had migrated less than 5 years ago. The first author, a Spanish researcher, moderated the FGDs assisted by another Spanish doctoral candidate who took notes, audio-recorded each session, and helped facilitate the discussion. FGD participants were asked about experiences of mothering and their meeting with Norwegian institutions.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the informants.

| Demographic data | Item | Italy (n=2) | Greece (n=2) | Spain (n=10) | Portugal (n=1) | Total (N=15) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Female | 2 | 2 | 7 | 0 | 11 | |

| Age (years) | 30-35 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 35-40 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | |

| 40-45 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 5 | |

| 45-50 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Education | Primary education | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Secondary education | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Higher education | 2 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 13 | |

| Years lived in Norway | 1-5 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| 5-10 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 9 | |

| 10-15 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| Number of children | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 8 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Number of children born in Norway | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 6 | |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Nationality of informants’ partners | Italian | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Greek | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Spanish | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | |

| Portuguese | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Norwegian | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 7 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

Eleven semi-structured interviews were conducted with eight Southern European mothers and four Southern European fathers. Most were one-on-one interviews (n=10), with one interview carried out with a couple (n=1). These were held in English (n=4) or Spanish (n=7) at a place of the interviewee's choosing, which included their workplaces, homes, a café, or the University. Five of the interviewees had participated in the FGDs and were invited to be interviewed because they were women with Norwegian partners, which was considered a factor shaping their experiences of mothering in a new country. The first author conducted all the interviews using an interview guide that contained exploratory questions around the themes of family backgrounds, life transitions, life in Norway, and parenthood. Interviews lasted between 75 and 120minutes and were digitally recorded. The first author transcribed the data verbatim.

Data were coded using NVivo12 software and analysed thematically following Braun and Clarke's model.19 The first author became immersed in the data, and inductively coded the dataset. Next, codes were arranged into initial themes and subthemes. The initial themes were reviewed against the dataset and reformulated considering the literature. This resulted in the definition of the final themes and subthemes. Finally, a report narrating the themes including quotes was discussed with the co-authors.

EthicsEthical approval was obtained from the Norwegian Data Protection Official. Written informed consent was provided by informants prior to data collection. During the FGDs, the first author highlighted the importance of respecting others’ opinions, and informants and co-moderator signed a non-disclosure agreement. To ensure confidentiality and anonymity, we have omitted details about informants’ personal situations, and quotations are presented anonymously.

ResultsThree themes related to parents’ experiences with RHS emerged: 1) coverage and organization of RHS; 2) relational experiences with health providers; and 3) pregnancy and delivery as a culturally-shaped event. Within each theme, the following subthemes were identified:

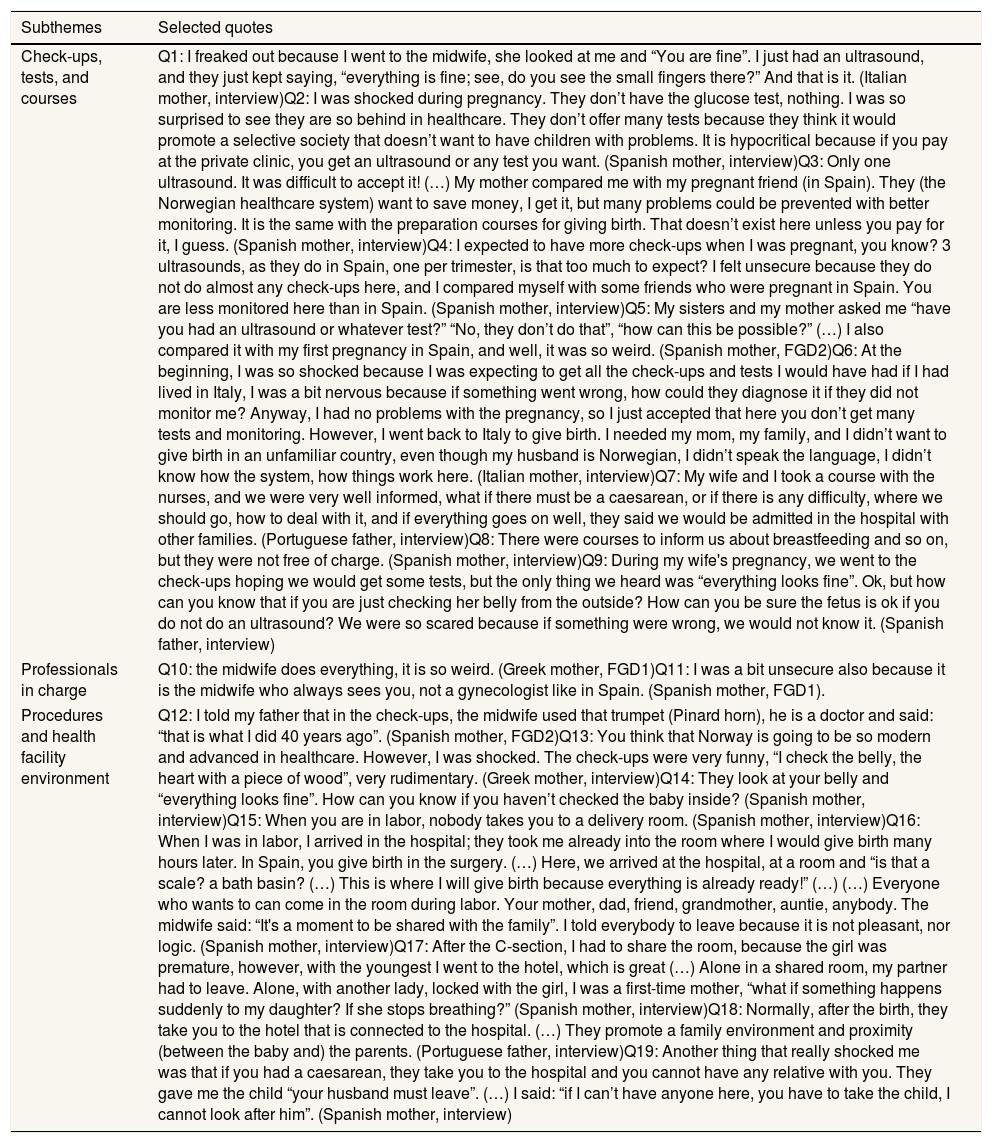

Coverage and organization of RHS (Table 2)1) Check-ups, tests, and coursesInformants shared that they received fewer antenatal checks and ultrasounds than they expected. Their perceptions that RHS had limited coverage were based on their comparisons between their experiences with these services and the experiences of friends or relatives who were pregnant in their countries of origin, who received more tests (Q4, Q5). Two informants also compared their own experiences with the Norwegian RHS and those from their countries of origin (Q5, Q6). Regarding childbirth preparation courses, informants shared their perceptions that these were not free of charge (Q3, Q7, Q8). Only one informant, who worked in healthcare and had an extended social network in Norway that included his in-law family, satisfactorily attended to a preparation course (Q7).

Theme “Coverage and organization of reproductive health services”.

| Subthemes | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Check-ups, tests, and courses | Q1: I freaked out because I went to the midwife, she looked at me and “You are fine”. I just had an ultrasound, and they just kept saying, “everything is fine; see, do you see the small fingers there?” And that is it. (Italian mother, interview)Q2: I was shocked during pregnancy. They don’t have the glucose test, nothing. I was so surprised to see they are so behind in healthcare. They don’t offer many tests because they think it would promote a selective society that doesn’t want to have children with problems. It is hypocritical because if you pay at the private clinic, you get an ultrasound or any test you want. (Spanish mother, interview)Q3: Only one ultrasound. It was difficult to accept it! (…) My mother compared me with my pregnant friend (in Spain). They (the Norwegian healthcare system) want to save money, I get it, but many problems could be prevented with better monitoring. It is the same with the preparation courses for giving birth. That doesn’t exist here unless you pay for it, I guess. (Spanish mother, interview)Q4: I expected to have more check-ups when I was pregnant, you know? 3 ultrasounds, as they do in Spain, one per trimester, is that too much to expect? I felt unsecure because they do not do almost any check-ups here, and I compared myself with some friends who were pregnant in Spain. You are less monitored here than in Spain. (Spanish mother, interview)Q5: My sisters and my mother asked me “have you had an ultrasound or whatever test?” “No, they don’t do that”, “how can this be possible?” (…) I also compared it with my first pregnancy in Spain, and well, it was so weird. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q6: At the beginning, I was so shocked because I was expecting to get all the check-ups and tests I would have had if I had lived in Italy, I was a bit nervous because if something went wrong, how could they diagnose it if they did not monitor me? Anyway, I had no problems with the pregnancy, so I just accepted that here you don’t get many tests and monitoring. However, I went back to Italy to give birth. I needed my mom, my family, and I didn’t want to give birth in an unfamiliar country, even though my husband is Norwegian, I didn’t speak the language, I didn’t know how the system, how things work here. (Italian mother, interview)Q7: My wife and I took a course with the nurses, and we were very well informed, what if there must be a caesarean, or if there is any difficulty, where we should go, how to deal with it, and if everything goes on well, they said we would be admitted in the hospital with other families. (Portuguese father, interview)Q8: There were courses to inform us about breastfeeding and so on, but they were not free of charge. (Spanish mother, interview)Q9: During my wife's pregnancy, we went to the check-ups hoping we would get some tests, but the only thing we heard was “everything looks fine”. Ok, but how can you know that if you are just checking her belly from the outside? How can you be sure the fetus is ok if you do not do an ultrasound? We were so scared because if something were wrong, we would not know it. (Spanish father, interview) |

| Professionals in charge | Q10: the midwife does everything, it is so weird. (Greek mother, FGD1)Q11: I was a bit unsecure also because it is the midwife who always sees you, not a gynecologist like in Spain. (Spanish mother, FGD1). |

| Procedures and health facility environment | Q12: I told my father that in the check-ups, the midwife used that trumpet (Pinard horn), he is a doctor and said: “that is what I did 40 years ago”. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q13: You think that Norway is going to be so modern and advanced in healthcare. However, I was shocked. The check-ups were very funny, “I check the belly, the heart with a piece of wood”, very rudimentary. (Greek mother, interview)Q14: They look at your belly and “everything looks fine”. How can you know if you haven’t checked the baby inside? (Spanish mother, interview)Q15: When you are in labor, nobody takes you to a delivery room. (Spanish mother, interview)Q16: When I was in labor, I arrived in the hospital; they took me already into the room where I would give birth many hours later. In Spain, you give birth in the surgery. (…) Here, we arrived at the hospital, at a room and “is that a scale? a bath basin? (…) This is where I will give birth because everything is already ready!” (…) (…) Everyone who wants to can come in the room during labor. Your mother, dad, friend, grandmother, auntie, anybody. The midwife said: “It's a moment to be shared with the family”. I told everybody to leave because it is not pleasant, nor logic. (Spanish mother, interview)Q17: After the C-section, I had to share the room, because the girl was premature, however, with the youngest I went to the hotel, which is great (…) Alone in a shared room, my partner had to leave. Alone, with another lady, locked with the girl, I was a first-time mother, “what if something happens suddenly to my daughter? If she stops breathing?” (Spanish mother, interview)Q18: Normally, after the birth, they take you to the hotel that is connected to the hospital. (…) They promote a family environment and proximity (between the baby and) the parents. (Portuguese father, interview)Q19: Another thing that really shocked me was that if you had a caesarean, they take you to the hospital and you cannot have any relative with you. They gave me the child “your husband must leave”. (…) I said: “if I can’t have anyone here, you have to take the child, I cannot look after him”. (Spanish mother, interview) |

Informants’ experiences of a mismatch between their expectations and the care received brought feelings of fear and dissatisfaction (Q1, Q2, Q3, Q9). They expressed feeling insecure about the fetus’ health because the monitoring was not enough and it was not adequate. Among the reasons they gave to the limited monitoring were economic (Q3), moral (Q2), and cultural (last theme).

2) Professionals in chargeInformants expressed surprise at finding out that nurse-midwives were responsible for prenatal check-ups, unlike in their countries of origin where gynecologists are the main professional providing antenatal care (Q10). This was accompanied by insecurity towards the attention a midwife could provide (Q11).

3) Procedures and health facility environmentInformants perceived that the procedures and technology employed during prenatal check-ups were different from those used in Southern Europe. In Norway, immigrant parents encountered non-invasive medical devices that are used because they do not interfere as much with the physiological process of childbearing. However, informants perceived this was out-of-date technology unable to provide an accurate diagnosis (Q12-Q14).

The immigrant parents in our study described the facilities used for labor and delivery in Norway through comparisons with those of Southern Europe, where the mother-to-be is moved from a labor to a delivery room. To their surprise, once admitted in the hospital, they were placed in a birthing-room that was equipped with all that was needed to assist the labor (Q15, Q16). Negative assessments of postnatal facilities were more common in the accounts of mothers who recovered from a C-section in a shared room with limited visitation rights. Being alone in an unfamiliar place brought feelings of stress and fear (Q17, Q19). Parents who experienced a normal birth were admitted in the “birth-hotel”, a building connected to the hospital. Informants shared positive experiences with this facility that promotes closeness among the family (Q17, Q18).

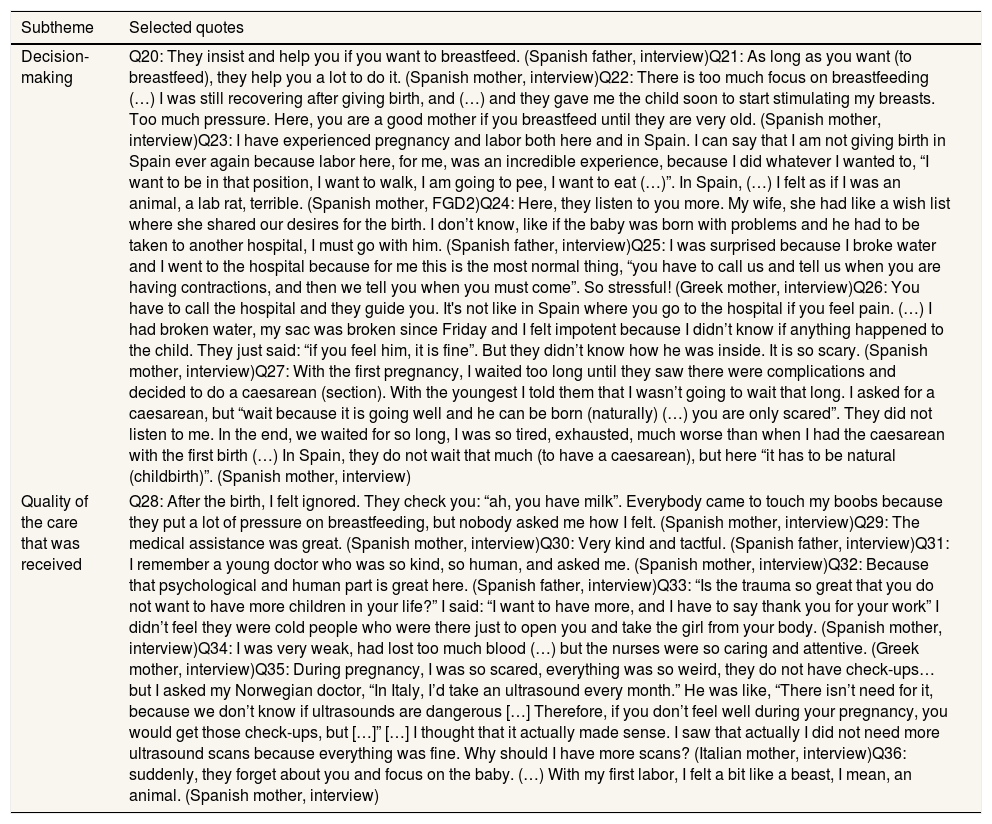

Experiences with health providers (Table 3)1) Decision-makingInformants’ accounts regarding the degree of decision-making experienced in the context of RHS were diverse. Some highlighted that it was easy to engage in collaborative relationships with health providers. This was contrasted to Southern Europe, where parents-to-be are treated in a more paternalistic manner. This resulted in informants attributing the success of their childbirth experiences to health providers’ attitudes, which were characterized by respect for the women's wishes (Q23, Q24). However, some perceived that the Norwegian health providers’ favorable attitudes towards vaginal birth could be an obstacle for good communication. These informants agreed that vaginal delivery is better than a C-section. However, in case of childbirth complications, they were worried that health providers would not listen to their opinions about the need for an emergency C-section and the risks of prolonged labor (Q27).

Theme “Experiences with health providers”.

| Subtheme | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Decision-making | Q20: They insist and help you if you want to breastfeed. (Spanish father, interview)Q21: As long as you want (to breastfeed), they help you a lot to do it. (Spanish mother, interview)Q22: There is too much focus on breastfeeding (…) I was still recovering after giving birth, and (…) and they gave me the child soon to start stimulating my breasts. Too much pressure. Here, you are a good mother if you breastfeed until they are very old. (Spanish mother, interview)Q23: I have experienced pregnancy and labor both here and in Spain. I can say that I am not giving birth in Spain ever again because labor here, for me, was an incredible experience, because I did whatever I wanted to, “I want to be in that position, I want to walk, I am going to pee, I want to eat (…)”. In Spain, (…) I felt as if I was an animal, a lab rat, terrible. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q24: Here, they listen to you more. My wife, she had like a wish list where she shared our desires for the birth. I don’t know, like if the baby was born with problems and he had to be taken to another hospital, I must go with him. (Spanish father, interview)Q25: I was surprised because I broke water and I went to the hospital because for me this is the most normal thing, “you have to call us and tell us when you are having contractions, and then we tell you when you must come”. So stressful! (Greek mother, interview)Q26: You have to call the hospital and they guide you. It's not like in Spain where you go to the hospital if you feel pain. (…) I had broken water, my sac was broken since Friday and I felt impotent because I didn’t know if anything happened to the child. They just said: “if you feel him, it is fine”. But they didn’t know how he was inside. It is so scary. (Spanish mother, interview)Q27: With the first pregnancy, I waited too long until they saw there were complications and decided to do a caesarean (section). With the youngest I told them that I wasn’t going to wait that long. I asked for a caesarean, but “wait because it is going well and he can be born (naturally) (…) you are only scared”. They did not listen to me. In the end, we waited for so long, I was so tired, exhausted, much worse than when I had the caesarean with the first birth (…) In Spain, they do not wait that much (to have a caesarean), but here “it has to be natural (childbirth)”. (Spanish mother, interview) |

| Quality of the care that was received | Q28: After the birth, I felt ignored. They check you: “ah, you have milk”. Everybody came to touch my boobs because they put a lot of pressure on breastfeeding, but nobody asked me how I felt. (Spanish mother, interview)Q29: The medical assistance was great. (Spanish mother, interview)Q30: Very kind and tactful. (Spanish father, interview)Q31: I remember a young doctor who was so kind, so human, and asked me. (Spanish mother, interview)Q32: Because that psychological and human part is great here. (Spanish father, interview)Q33: “Is the trauma so great that you do not want to have more children in your life?” I said: “I want to have more, and I have to say thank you for your work” I didn’t feel they were cold people who were there just to open you and take the girl from your body. (Spanish mother, interview)Q34: I was very weak, had lost too much blood (…) but the nurses were so caring and attentive. (Greek mother, interview)Q35: During pregnancy, I was so scared, everything was so weird, they do not have check-ups…but I asked my Norwegian doctor, “In Italy, I’d take an ultrasound every month.” He was like, “There isn’t need for it, because we don’t know if ultrasounds are dangerous […] Therefore, if you don’t feel well during your pregnancy, you would get those check-ups, but […]” […] I thought that it actually made sense. I saw that actually I did not need more ultrasound scans because everything was fine. Why should I have more scans? (Italian mother, interview)Q36: suddenly, they forget about you and focus on the baby. (…) With my first labor, I felt a bit like a beast, I mean, an animal. (Spanish mother, interview) |

Informants discussed their decision-making experiences around being admitted to the childbirth facilities. For them, it was a “shock” that when the woman was in labor, she was expected to call the hospital and be guided about the steps to take from home. Based on their experiences with healthcare services in Southern Europe, informants wanted to be admitted to the hospital and monitored from the beginning of the labor. Their experiences of being sent back home or told to stay at home brought fear and stress (Q25, 26). This extended to breastfeeding, where we found different accounts for the degree of decision-making experienced. While some mothers experienced health providers’ focus on breastfeeding as pressure (Q20), others, who had always been willing to breastfeed, reported feeling supported by the health providers in their decision (Q20-Q22).

2) Quality of the care receivedInformants positively assessed the treatment received from health providers during pregnancy, especially when professionals explained why there were not as many ultrasound scans as expected (Q35). Regarding their experiences of childbirth, the majority highlighted that health providers were caring and psychologically supportive (Q29-Q34). Mothers who had a C-section and were admitted in a shared room without their partners shared less positive experiences. They complained about health providers who approached them to check their milk production (Q28) and seemed to care more for the baby than for them (Q36).

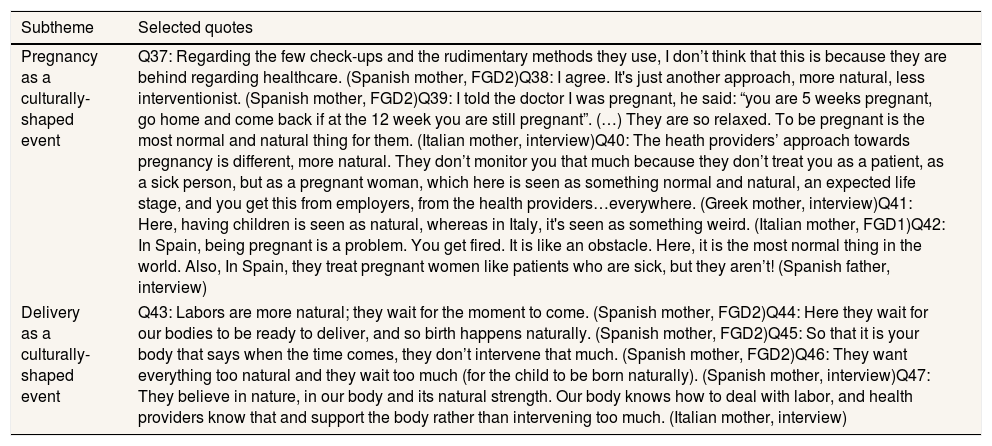

Pregnancy and delivery as a culturally-shaped event (Table 4)1) Pregnancy as a culturally-shaped eventTo make sense of their experiences with Norwegian RHS, informants reflected on the cultural understandings around pregnancy they perceived as dominant in the country. The immigrant parents in our study discussed that fewer monitoring was the result of a less interventionistic healthcare system that understands pregnancy as a natural experience (Q37-Q40). They reflected on the more paternalistic and interventionistic approach towards pregnancy that characterises Southern European healthcare systems. Informants discussed that in these countries, pregnancy was understood as a life disruption (Q41, Q42). On the contrary, based on their experiences with employers and professionals, they perceived that pregnancy was constructed as a positive experience in Norway. Informants discussed that, framed by these cultural understandings, Norwegian health providers would guide, not monitor, the parents-to-be.

Theme “Pregnancy and delivery as a culturally-shaped event”.

| Subtheme | Selected quotes |

|---|---|

| Pregnancy as a culturally-shaped event | Q37: Regarding the few check-ups and the rudimentary methods they use, I don’t think that this is because they are behind regarding healthcare. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q38: I agree. It's just another approach, more natural, less interventionist. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q39: I told the doctor I was pregnant, he said: “you are 5 weeks pregnant, go home and come back if at the 12 week you are still pregnant”. (…) They are so relaxed. To be pregnant is the most normal and natural thing for them. (Italian mother, interview)Q40: The heath providers’ approach towards pregnancy is different, more natural. They don’t monitor you that much because they don’t treat you as a patient, as a sick person, but as a pregnant woman, which here is seen as something normal and natural, an expected life stage, and you get this from employers, from the health providers…everywhere. (Greek mother, interview)Q41: Here, having children is seen as natural, whereas in Italy, it's seen as something weird. (Italian mother, FGD1)Q42: In Spain, being pregnant is a problem. You get fired. It is like an obstacle. Here, it is the most normal thing in the world. Also, In Spain, they treat pregnant women like patients who are sick, but they aren’t! (Spanish father, interview) |

| Delivery as a culturally-shaped event | Q43: Labors are more natural; they wait for the moment to come. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q44: Here they wait for our bodies to be ready to deliver, and so birth happens naturally. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q45: So that it is your body that says when the time comes, they don’t intervene that much. (Spanish mother, FGD2)Q46: They want everything too natural and they wait too much (for the child to be born naturally). (Spanish mother, interview)Q47: They believe in nature, in our body and its natural strength. Our body knows how to deal with labor, and health providers know that and support the body rather than intervening too much. (Italian mother, interview) |

Informants discussed that childbirth in Norway was framed by a cultural understanding of delivery as a natural and beautiful experience to be shared with family (Q43-Q47). They shared that in the host country there is a belief in the capacity of the human body to recover from physical difficulties, which shapes RHS provision and organization.

DiscussionThe findings identified main themes regarding how immigrant parents perceived and experienced childbirth in Norway. First, informants portrayed Norway as an unfamiliar place to give birth. In this regard, informants’ immigrant-status can be a source of their vulnerability to experience environmental stressors. The lack of knowledge about the RHS and of social support might have hindered immigrant parents from feeling safe in the environment where they became parents. Particularly, informants’ experiences were influenced by factors like support from social networks and partner presence during childbirth.20,21 Informants stressed how much they missed sharing their experiences with their families, which shows how social networks influenced their childbearing and childbirth experiences.3

Secondly, most informants did not take any birth preparation courses because they assumed these were not free of charge in Norway. This shows their lack of knowledge about the services, which may have been reinforced by their reported feelings of isolation. An extensive social network would have helped them to navigate the health system, including getting accurate information and the support that expecting parents need. Research shows that antenatal preparation and access to information about childbirth promote positive experiences.20 These courses help expecting parents to make friends,22 which can be especially valuable for immigrants’ integration in a new country.

Thirdly, we found mixed experiences of satisfaction with RHS. Dissatisfaction was prompted by how informants’ expectations of the services and the actual experience differed. This despite that Norwegian antenatal guidelines are in line with the World Health Organization's recommendation of a minimum of eight antenatal consultations.23 Based mostly on experiences that their friends and family had in Southern Europe, informants formed their expectations about antenatal care.24 These expectations reinforced their dissatisfaction with the Norwegian RHS, which they assessed as deficient. Dissatisfaction with RHS was more common in the accounts of women who were afraid of long labor and had expectations about the possibility to have a C-section. When such expectations were not met by health providers, they felt abandoned and dissatisfied. This is consistent with research showing that powerlessness during childbirth is associated with negative experiences.25 On the contrary, a woman's acceptance of pain and positive perception of her ability to give birth promotes positive childbirth experiences.26 A Norwegian study similarly found that women who understood pain as a natural component of childbirth were more likely to experience childbirth positively.20 Childbirth preparation should be thus available and incorporate a natural vision on childbirth that helps women to understand its physiology.

Regarding positive experiences with RHS, consistent with previous studies,27 informants highly valued mothers’ involvement in childbirth. Furthermore, they emphasized the caring attitude of health providers as a factor that brought satisfactory experiences. This shows how interpersonal relations that incorporate emotional needs foster satisfaction.23 As for the health facilities, informants who were admitted to the birth-hotel shared positive opinions regarding the family-oriented and non-medicalized environment. This resonates with research that stressed the importance of a warm environment promoting humanized care in RHS.28

Our informants’ experiences with RHS were shaped by the dissonance between their expectations, which were bounded by their own culture, by the experiences of others back home, and by the services provided in Norway. The clashes that these immigrant parents felt reflect how cultural understandings of the body informs and shapes RHS, including the use of technology, the relationship between provider and patient, and the experience of giving birth in a health facility. Informants identified a predominant trust in the body's capacity to give birth in Norway. Based on this, they perceived that women receive the support they need to cope with the physiological process of childbirth through the midwifery system. This contrasts to the experiences that others from their countries of origin shared, where women are treated as patients who need an intervention.

Southern European societies hold a natural view on childbearing that has not been successfully reflected in their RHS.29 This is manifested in the high numbers of C-sections, in the important place that gynecologists are awarded in the antenatal care process, and in the competition between these professionals and midwives.29 This context influenced our informants’ expectations of being assisted by gynecologists who would use state-of-the-art tests and machines. Informants expressed disdain for the ‘old-fashion’ techniques prevalent in Norway and felt uneasy about the scarce use of tests. This is in line with a Spanish study that found that women see RHS technology as a source of security.30 However, changes have been implemented to Southern European RHS since our informants emigrated. Research shows that efforts towards the de-medicalisation of RHS have resulted in a transformation of attitudes and practices in Spain, and that these new policies were met with strong resistance, particularly in areas like decision-making and risk-management.31

The limitations of the study include that one FGD and seven interviews were conducted in English, which was not informants’ native language. Moreover, fathers were underrepresented in the sample and we did not have a large enough number of informants from each country, which was a limitation for the analysis. Regarding data saturation, no new information related to experiences of RHS were observed after coding nine interviews. The first author's insider position facilitated the collection of rich data but it might have brought possible bias to the analysis. To minimize this, the co-authors, with different personal and professional backgrounds, participated in the formation and discussion of the themes.

A larger study would benefit from interviewing both immigrant parents and health providers about their experiences with RHS. Likewise, further research should include Southern European immigrants with recent experiences with the RHS from their countries of origin. The recent efforts to de-medicalize childbirth in these countries may result in fewer experiences of a cultural clash. In any case, our study provides relevant insights into immigrants’ experiences with RHS in a new country and how these are shaped by experiences and expectations formed in a complex context.

ConclusionThe findings suggest that developing culturally competent healthcare systems and interventions is needed to address disparities in healthcare access and utilization between immigrants and nationals. Individuals experience and understand childbearing framed by cultural beliefs. Healthcare providers need to problematize their cultural understandings, the methods and organization of RHS to avoid taken-for-granted assumptions. Acknowledging differences in approaches towards childbearing would set the stage for collaboration between users and providers.

Immigration brings new challenges for reproductive health services and practices. In Norway, research has found that non-western immigrant women are at risk of poorer maternal outcomes, and healthcare providers have been criticized for lacking cultural sensitivity and competence.

What does this study add to the literature?The study presents the experiences of Southern European immigrant parents with the Norwegian Reproductive Health Services, and their perceptions of health providers’ beliefs regarding pregnancy and childbirth

What are the implications of the results?To ensure equity in reproductive healthcare, health providers should acknowledge cultural diversity and mothers’ emotional needs, as well as involve both mothers and fathers in decision-making.

Erica Briones-Vozmediano.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionR. Herrero-Arias is responsible for the article and contributed to the conception and management of the work, to the recruitment of participants, to the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, the critical review and the final writing of the manuscript, with relevant intellectual contributions. G. Ortiz-Barreda contributed to the conception of the work, to the analysis of data, and to the critical review of the article with relevant intellectual insights. M. Carrasco-Portiño contributed to the critical review of the article with important intellectual contributions. All authors are responsible for having reviewed aspects of the manuscript.

FundingThis study is part of a Ph.D. research project financed by the University of Bergen, Norway.

Conflict of interestThe authors do not report any conflict of interest.