Analyzing the variations in induced abortion (IA) rates across different subpopulations in Spain based on country of origin, while considering educational and age composition.

MethodUsing 2021 Voluntary Termination of Pregnancy register and 2021 Spanish Census microdata, we calculated crude IA rates and age-specific abortion rates. We used age-standardized IA rates (ASIAR) to account for the confounding effect of age composition. We compared seven subpopulations residing in Spain, taking into account simple ages and educational levels aggregated into four categories.

ResultsImmigrant women, especially those from Sub-Saharan and Latin American countries, consistently had higher IA rates compared to native Spanish women. According to age-specific IA rates, university-educated women had considerably fewer abortions than women with other education levels at any age. Age-standardized rates stratified by migratory origin revealed that native Spanish women with primary education or less had higher IA rates than their immigrant counterparts. There was a clear non-linear, association between educational level and IA rates among immigrants. The highest propensity for IA was found among secondary school graduates, while university graduates had the lowest IA rate.

ConclusionsThe study demonstrated that variability in sociodemographic characteristics had an impact on IA rates. Young women with middle educational attainment and immigrant background had a higher likelihood of undergoing IA in Spain. The relationship between educational level and IA rates was complex, with variations observed among different groups and changes over time.

Analizar las variaciones en las tasas de aborto inducido (AI) en diferentes subpoblaciones en España según el país de origen y considerando la composición por edad y educación.

MétodoUtilizando el Registro de Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo de 2021 y el censo español de 2021, se calcularon las tasas brutas de AI y las tasas específicas por edad para diferentes subgrupos, así como las tasas de AI estandarizadas por edad para tener en cuenta el efecto confusor de la composición por edad. Se compararon siete subpoblaciones residentes en España, teniendo en cuenta la edad y el nivel educativo agregado en cuatro categorías.

ResultadosLas mujeres inmigrantes, en especial las provenientes de países subsaharianos y latinoamericanos, tenían tasas de AI consistentemente más altas que las mujeres españolas. Las tasas específicas por edad revelaron que las mujeres con educación universitaria tuvieron considerablemente menos AI en todas las edades que las mujeres con niveles educativos inferiores. Sin embargo, estas tasas variaban entre los diferentes grupos de mujeres inmigrantes. Las tasas estandarizadas por edad y estratificadas por origen migratorio revelaron que las mujeres españolas con educación primaria o inferior tenían tasas más altas de AI que las mujeres inmigrantes con el mismo nivel educativo. Entre las inmigrantes, se observó una clara asociación no lineal entre el nivel educativo y las tasas de AI: la mayor propensión al AI se encontró entre las tituladas de educación secundaria, mientras que las graduadas universitarias tuvieron la tasa de AI más baja.

ConclusionesEl estudio demostró que la variabilidad en las características sociodemográficas de los grupos tuvo su impacto en las tasas de AI. Las mujeres jóvenes españolas con menor nivel educativo y las inmigrantes tuvieron una mayor probabilidad de someterse a AI en España. La relación entre el nivel educativo y las tasas de AI es compleja, con variaciones observadas entre diferentes grupos y cambios a lo largo del tiempo.

Over the past 25 years, high-income countries have seen significant reductions in induced abortion (IA) rates. The overall abortion rate decreased by 31%.1 Despite this change, recent studies have demonstrated persistent inequalities in the use of IA, with strong associations found among young age, immigrant origin, poor educational attainments, low socioeconomic status, and economic precariousness.2–6

In line with findings in other high-income countries, the evidence for Spain reveals that the likelihood of undergoing an IA is strongly associated with several sociodemographic features such as a woman's age, number of children, and partnership stability.7 Several studies highlight the importance of socioeconomic status disparities, particularly low levels of education, low occupational status, and limited access to economic resources, as key predictors of IA.8–11 Solid evidence indicates that immigrants have a significantly higher likelihood of undergoing an IA, thereby making a substantial contribution to overall IA rates at the population level in countries with large immigrant communities.12–14 Language barriers and limited knowledge of their rights and the healthcare system in Spain have been identified as possible explanations for the higher rates of IA among immigrants.15,16 It has been also suggested that the higher levels of IA among immigrants may be linked to lower educational levels, job precariousness, and poverty.15–18

Despite previous contributions to our understanding of IA in Spain, there is a growing demand for new research to delve into this phenomenon in a country that (1) experienced substantial transformations in the past decade, like the implementation of a new abortion regulation in 2010, fluctuations in immigrant influx, economic cycle changes, and the recent impact of the Covid-19 pandemic; and (2) where the effect of compositional factors on the variability of IA rates across different subpopulations has not been systematically explored. More specifically, little is known about the combined impact of socio-demographic composition in terms of age structure and educational attainment on disparities in IA among native and foreign-born women. Finally, it is worth noting that studies on IA patterns have often focused on analyzing municipal and regional-level data, while national-level analyses have been less common18,19.

Although legal access to IA gives women a high degree of autonomy and control over their reproductive trajectories, the social differences in IA rates reveal the persistence of multidimensional stratification in terms of access to contraception and family gynecological healthcare services.20 As suggested from an intersectional framework, the increased likelihood of IA among certain population groups is not simply a result of the combination of individual and social characteristics, but rather an articulation of a hierarchical system of systemic inequalities based on gender, class, economic situation, ethnicity, race, and age.21 While in recent studies on IA the intersectional approach was primarily used to understand the effects of inequality structures in terms of race and gender, it is also possible to apply this perspective for analyzing other factors of social differentiation such as migratory origin, education, and age.22

In recent years, a growing body of research has been aimed at quantitatively investigating the cumulative impact of multiple dimensions of social inequality on health outcomes.23,24 Standardization and decomposition analysis are methods used to advance this line of research.25 These approaches allow for measuring the combined effect of various characteristics on specific outcomes, while isolating them from compositional factors.26 Nevertheless, these techniques have been scarcely used to address the disparities in IA rates among subpopulations differentiated across multiple axes of social inequalities.27

Against this background, the main objective of this paper is to explore, through standardization techniques, the extent to which differences in IA rates between native Spanish and immigrants depend on their educational attainment and age structure disparities.

MethodThis population-based study was conducted making use of two different data sources to produce the period IA rates that constituted its main measures. First, we used microdata from the register of voluntary terminations of pregnancy provided, after due ad hoc request, by the Spanish Ministry of Health for the period 2011-2021. Detailed information on how the register is constructed and organized and the information it contains can be found on the website of the Ministry of Health.28 We compute the numerators of the rates from this register. Secondly, data from the 2021 Population and Housing Census microdata (available on the website of the National Statistics Institute29) provided the denominators of the rates. Both data sources are publicly accessible and free of charge. Data from the 2011 Census are used to compute the rates of IA by education and evaluate change over time.

The main exposures are age, educational attainment, and migratory origin. Age is treated on a disaggregated, year-by-year basis. To differentiate educational attainment, we distinguish four levels: primary and below, lower secondary, upper secondary, and university. Countries of birth were grouped into seven categories, combining their level of economic development with their cultural backgrounds: Spanish natives, high-income countries (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Sweden, Switzerland, Monaco, Andorra, Norway, United Kingdom, Israel, United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore), rest of Europe (Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Georgia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Malta, Moldavia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Ukraine), North Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, and Tunisia), Sub-Saharan Africa (rest of African countries), rest of America (American countries not included among high-income countries), and rest of Asia and Oceania (not previously included among high-income countries).

The quality of the information and the large number of observations we use make possible a detailed analysis of the association of educational level with IA while controlling for country of origin. From these data we can compute and compare IA rates in the twenty-eight population groups resulting from crossing the four educational levels with the seven groups of countries of migrant origin. Moreover, with the distributions of IA and female population in each group by simple ages, we can control for confounding due to age using age-specific and age-standardized rates. Thus, our empirical strategy follows three steps. First, we calculate separately for each educational level and migration origin the IA rates by dividing the number of IAs by the female population exposed to the risk of having an IA. We also calculate age-specific rates for different educational levels and migration origins separately. Finally, considering that not only the differential behaviors at each age but also differences in the age composition of the subgroups can confound the actual experience of IA when comparing them, we control for age composition using age-standardized IA rates (ASIAR). The ASIARs result from multiplying the age-specific rates of IA for a given group by the proportion of a standard population, S, that corresponds to each age. Thus, the ASIAR for group A is computed as:

where Aax are the age-specific IA rate for the group A at age x and SCx is the proportion of each age x in the standard population S. Following a common solution in this type of exercise, the whole female population resident in Spain in 2021 between 12 and 52 years of age will be used as the standard population. Age-standardized rates tell us how a given subgroup would behave if, given the observed rates, it had the age structure of the standard population. In other words, age-standardized rates control or cancel out the part of the differences among crude rates of different subgroups that correspond to their age composition.

ResultsTable 1 shows the number of IA in Spain in 2021 distributed by age bands, educational attainment, country of birth, and the interaction education/origin. The table also includes the corresponding distributions for respective female populations. In 2021 90,189 IA were performed in Spain. Of these, 89,950 cases with complete information on the variables of interest could be retrieved for the operational database used for this study. More than half of these IA performed in Spain (52.6%) were carried out on women under the age of 30, who had very low fertility rates and represented approximately only one third of the female population of reproductive age. Women without university degrees were also disproportionately affected, as 80% of IA were performed on non-graduate women, despite only representing 70% of the female population at risk of unintended pregnancies. Migrant women were more likely to have had IA than native women. Although they only represented one in five women of reproductive age, they accounted for 35% of IA in Spain. In summary, young women with lower or medium educational attainment and of immigrant origin were more likely to resort to IA in Spain. IA rates also shown in Table 1 confirmed these initial observations. Women with low to medium levels of education have higher rates of IA than women with university education. However, the relationship between education level and IA was not linear, as the highest rates were found among women with secondary education (10.1 per 1,000 for lower secondary and 7.8 for upper secondary).

Descriptive statistics. Distribution of abortions and female population 12-52 and induced abortion rates for subgroups in Spain, 2021. Rates per 1000 women.

| Abortions | Population | Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Women 12-52 | 89,950 | 100 | 12,299,995 | 100 | 7.3 |

| Age (years) | |||||

| 12-19 | 9,377 | 10.4 | 1,916,088 | 15.6 | 4.9 |

| 20-24 | 18,720 | 20.8 | 1,148,291 | 9.3 | 16.3 |

| 25-29 | 19,182 | 21.3 | 1,244,148 | 10.1 | 15.4 |

| 30-34 | 18,590 | 20.7 | 1,380,594 | 11.2 | 13.5 |

| 35-39 | 16,136 | 17.9 | 1,621,024 | 13.2 | 10.0 |

| 40-52 | 7,945 | 8.8 | 4,989,850 | 40.6 | 1.6 |

| Education | |||||

| Primary or less | 11,890 | 13.2 | 1,616,204 | 13.1 | 7.4 |

| Lower secondary | 29,204 | 32.5 | 2,886,910 | 23.5 | 10.1 |

| Upper secondary | 31,650 | 35.2 | 4,058,683 | 33.0 | 7.8 |

| University | 17,206 | 19.1 | 3,738,198 | 30.4 | 4.6 |

| Country of birth | |||||

| Spain | 57,905 | 64.2 | 9,632,961 | 78.3 | 6.0 |

| High-income countries | 3,684 | 3.4 | 414,563 | 3.4 | 8.9 |

| Rest of Europe | 4,186 | 4.7 | 400,391 | 3.3 | 10.5 |

| North Africa | 3,371 | 3.8 | 313,794 | 2.6 | 10.7 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 1,322 | 1.5 | 69,187 | 0.6 | 19.1 |

| Rest of America | 17,671 | 19.6 | 1,298,928 | 10.6 | 13.6 |

| Rest of Asia & Oceania | 1,811 | 2.0 | 170,171 | 1.4 | 10.6 |

| Country of birth by education | |||||

| Spain | |||||

| Primary or less | 7,250 | 12.5 | 975,044 | 10.1 | 7.4 |

| Lower secondary | 18,803 | 32.5 | 2,316,578 | 24.0 | 8.1 |

| Upper secondary | 19,327 | 33.4 | 3,209,566 | 33.3 | 6.0 |

| University | 12,525 | 21.6 | 3,131,773 | 32.5 | 4.0 |

| High income countries | |||||

| Primary or less | 176 | 4.8 | 56,072 | 13.5 | 3.1 |

| Lower secondary | 816 | 22.1 | 63,453 | 15.3 | 12.9 |

| Upper secondary | 1,505 | 40.9 | 132,190 | 31.9 | 11.4 |

| University | 1,187 | 32.2 | 162,848 | 39.3 | 7.3 |

| Rest of Europe | |||||

| Primary or less | 890 | 21.3 | 106,167 | 26.5 | 8.4 |

| Lower secondary | 1,450 | 34.6 | 99,521 | 24.9 | 14.6 |

| Upper secondary | 1,308 | 31.2 | 118,930 | 29.7 | 11.0 |

| University | 538 | 12.9 | 75,773 | 18.9 | 7.1 |

| North Africa | |||||

| Primary or less | 1,287 | 38.2 | 150,589 | 48.0 | 8.5 |

| Lower secondary | 1,156 | 34.3 | 87,509 | 27.9 | 13.2 |

| Upper secondary | 665 | 19.7 | 54,619 | 17.4 | 12.2 |

| University | 263 | 7.8 | 21,077 | 6.7 | 12.5 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | |||||

| Primary or less | 369 | 27.9 | 26,329 | 38.1 | 14.0 |

| Lower secondary | 446 | 33.7 | 20,445 | 29.6 | 21.8 |

| Upper secondary | 388 | 29.3 | 16,157 | 23.4 | 24.0 |

| University | 119 | 9.0 | 6,256 | 9.0 | 19.0 |

| Rest of America | |||||

| Primary or less | 1,523 | 8.6 | 247,818 | 19.1 | 6.1 |

| Lower secondary | 5,889 | 33.3 | 256,752 | 19.8 | 22.9 |

| Upper secondary | 7,947 | 45.0 | 488,005 | 37.6 | 16.3 |

| University | 2,312 | 13.1 | 306,353 | 23.6 | 7.5 |

| Rest of Asia & Oceania | |||||

| Primary or less | 395 | 21.8 | 54,185 | 31.9 | 7.3 |

| Lower secondary | 644 | 35.6 | 42,652 | 25.1 | 15.1 |

| Upper secondary | 510 | 28.2 | 39,216 | 23.1 | 13.0 |

| University | 262 | 14.5 | 33,856 | 19.9 | 7.7 |

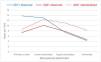

A comparison of IA rates by education level in 2011 and 2021 (Fig. 1) shows that the role of education has changed over time. Whereas in 2011 the relationship between IA and education was monotonically negative, in 2021 it is curvilinear: the lowest propensity to abort is concentrated among university-educated women; the highest propensity is concentrated among women with intermediate levels of education. The change in the form of association between educational attainment and IA is also visible when the rates observed in 2011 are compared with the standardized rates for 2021 (using the 2011 age structure). This suggests that changes in population structure have not affected the change in the pattern of association between educational attainment and IA, although to some extent they have reduced the rates at all educational levels. Interestingly, IA observed rates in 2021 are lower than in 2011 at all educational levels except upper secondary. Moreover, as expected, immigrant women —especially those from Sub-Saharan (19.1) and Latin American (13.6) countries— had consistently higher crude rates of IA compared to native Spanish women, who had the lowest rate (6.0) among all countries of birth.

The age-specific rates by educational attainment and country of birth provide a more accurate perspective than the crude rates. With regards to educational attainment (Fig. 2), university-educated women had considerably fewer abortions than women with other education levels at any age. Women with primary education or less had more IAs than other groups before the age of nineteen and above the age of thirty. Women with lower secondary education had the highest rates in their first twenties, while women with upper secondary education fell below the lower educational levels until the age of thirty, after which they caught up with those with primary education or less. Age-specific rates confirm the curvilinear, inverted U-shape of the relationship between IA and education. Regarding country of birth, all immigrant groups had higher age-specific rates of IA than native Spanish women (Fig. 3). Only Asian women (excluding those from high-income countries) had lower IA rates at young ages than Spanish women, who had fewer abortions at all other ages than the rest of the groups. Women born in high-income countries closely resembled Spanish women, with a slightly higher IA rate. At the opposite extreme, it was Sub-Saharan women who showed the highest levels of IA at virtually all ages, followed by Latin American women.

By construction, part of the differences in crude rates are due to heterogeneous behavior in the different subgroups, part to the different composition of their populations. Considering that women with different educational endowments differ in their age profile and migration background, one may ask how much of the difference in IA rates between levels of education can be attributed to compositional effects. Age-standardized rates and stratification by migratory origin provide an answer. Since the educational attainment of migrant women is generally lower than that of native Spanish women,30 it is tempting to think that the observed educational differences in IA rates were due to differences in the migratory composition of the groups. However, a more complex reality emerges if the two factors are interacted and age-standardized rates are calculated for each resulting category (Fig. 4). Native Spanish women with primary education or less had abortions much more frequently than immigrant women with the same level of education in all migrant groups. This high standardized rate of poorly educated Spanish women is not due to any composition effect, but to age-specific rates that far exceed those of all other immigrant groups, especially after the age of 25. This was not the case among female university graduates, among whom standardized rates tend to coincide with crude rates in all groups. Regarding lower and upper secondary school graduates, immigrant women with these intermediate educational levels had higher standardized rates of IA than Spanish women, while women from Central and South America and Sub-Saharan countries had the highest rates. In terms of standardized rates, there was a clear non-linear, inverted U-shaped association between educational level and IA rates in all migrant groups, but not among Spanish natives. That is, among all immigrants, the highest propensity for IA was found among secondary school graduates, and except in the case of native Spanish, the differences between university graduates and women with lowest educational credentials tended to be small.

DiscussionDifferentials in IA rates among socio-demographic categories have been well-documented in the literature,9,11,13 yet the possibility that these disparities stem from variations in group compositions has not been sufficiently explored. This study addresses this gap by examining the interaction between educational attainment and country of origin while controlling for age through direct standardization.

Our study confirms that age and education are associated with a higher likelihood of abortion.3,5,22 It also reveals that the risk of IA among migrant women (12 per 1,000) is nearly twice as high as that among native-born women (6 per 1,000). These findings confirm patterns observed in numerous Spanish studies conducted before 2021 at both national and regional levels, as well as in studies conducted in other countries.

However, our study goes beyond merely establishing a simple association between origin and IA, as it also explores the combined effects of two other key factors: educational level and age. While our analyses confirm findings from other studies indicating that IA variability is associated with educational level,10,16 it also reveals that between 2011 and 2021, the educational profile of women seeking IA in Spain changed. What was essentially a monotonic pattern of negative association with education became a curvilinear, inverted U-shaped relationship: women who in 2021 had more IA were those with intermediate levels of education (lower secondary or upper secondary); women with primary school or less and university education had fewer abortions this year. Additionally, age-specific IA rates confirm that this pattern of curvilinear association with education is present throughout much of the twenties, the ages at which most IA occur. All groups of immigrant women, irrespective of their origin, share these characteristics. In other words, during the last decade, the impact of the intersection of migratory background and educational attainment on IA changed in Spain, altering the pattern of inequality.

The analyses of the interaction between educational attainment and country of origin while controlling for age through direct standardization show a clear differential pattern between native and immigrant women. If all observed groups of women had the same age structure, women of immigrant origin would maintain the pattern of curvilinear educational inequality we have noted, with the highest levels of IA among women with secondary education; nevertheless, among native-born women, the practice of IA that would be found would be a marked negative association with education, with a disproportionate concentration of IAs among women with low levels of education and decreasing intensities as educational level increases, as has been observed in previous research.10

Given the limitations of the available data, we cannot be certain why the association of educational attainment with IA risk is different for native-born and immigrant women. We know that the bulk of these differences are not due to group composition effects but to differences in rates. But behavioral differences, unrelated to group characteristics, are difficult to explain with the data available today. In the case of natives, a commonly accepted hypothesis is that the risk of IA depends on information about contraception and reproductive health, as well as better access to family planning services, which, in turn, is associated with higher educational attainment.4,31 However, this hypothesis does not hold for immigrant foreign-born women, among whom secondary education graduates have more IAs than women with university education graduates. Similar patterns were observed in other high-income countries.32 Furthermore, a previous study9 on the decision to abort among women in Barcelona found that educational inequalities in AI disappeared among women who did not have a partner. Different characteristics concerning the partnership status of native and immigrant women might be relevant to account for their differential IA rates, but our data do not allow us to verify this. Some alternative explanatory hypotheses can be suggested for future studies. One possibility is that the levels of induced IA recorded in Spain for migrant women reflect the levels observed in their regions of origin, with which they tend to be congruent.33 Especially in more traditional groups, women with lower levels of education may be more exposed to pressures from the group regarding obedience to norms that prohibit abortion.34 Moreover, one can speculate that the circumstances of migration, including possible partner instability and lack of support networks in destination countries, outweigh the information assumed to be associated with educational credentials.

At least two limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the analysis relies, for the most part, on aggregated data, which may mask individual-level variations and nuances within the population. Although we use microdata to obtain the numerators and denominators of the rates, we do not have a single microdata base that includes women who had abortions and those who did not. Microdata files were used to construct the aggregated data on which we developed our analysis. However, since there are no common identifiers in both databases, linking them on a case-by-case basis is ruled out for the time being. Second, and for the same reasons, the study does not account for potential confounding factors both individual —parity, partnership status, o previous history of abortions— and contextual —cultural differences, language barriers, or specific legal and healthcare access issues— that could influence the observed disparities in abortion rates between educational levels and migratory backgrounds.

These limitations highlight the need for further research in this area to fully understand this complex reality. In any case, to reduce the rates of unwanted pregnancies and IA in Spain, it will be useful to design policies focused on immigrant women, especially those coming from Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as natives with low educational levels.

Availability of databases and material for replicationData on induced abortions come from the register of voluntary terminations of pregnancy (available upon request from Spanish Ministry of Health). Data on population come from the 2021 Population and Housing Census (available on the website of the National Statistics Institute, www.ine.es).

Age, and socioeconomic status, including education and economic resources, are key predictors of induced abortion, with immigrants having a higher likelihood of undergoing an abortion. These disparities are often attributed to lower socioeconomic attainment among immigrants, but differences in demographic composition can also be very relevant.

What does this study add to the literature?Differences in abortion rates between Spanish and immigrant women are mediated by educational levels. Among Spanish women, when age is controlled for through standardization, abortion rates decrease as educational level increases. In contrast, for immigrant women, this relationship is curvilinear, with women with secondary education exhibiting the highest rates of abortion compared to those with the lowest and highest educational attainment.

What are the implications of the results?The variability in induced abortion rates among women of different origins and educational attainments underscores the importance of developing reproductive health policies well adapted to specific educational profiles of the target populations.

Julia Díez.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsM. Requena conceived the study, carried out the analysis and drafted the first version of the manuscript. M. Stanek participated in the design of the analysis and contributed to writing, discussing the results, and reviewing the manuscript.

FundingThis work supported by Grant PID2021-128108OB-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and ERDF A way of making Europe and R&D Activities Program in Social Sciences and Humanities, Community of Madrid, Grant H2019/HUM-5802.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest. The funders do not have any involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, nor in the writing of the report, and the decision to submit the paper for publication.