To determine the attitudes towards equality and prevention of gender-based violence, and analyze variables associated with a higher awareness of gender-based violence by students of the health sciences and social work degrees.

MethodA cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out. The sample consisted of 437 students of the health sciences and social work degrees at the University of Zaragoza (Spain) during 2018 and 2019. The variables of the study were: Socio-demographic variables, academic variables, feminism attitudes towards women's movement using Feminism and the women's movement scale (FWMS), attitudes on gender-based violence using the Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender-based Violence Scale (GEPGVS). A correlational study and multiple linear regression were performed, in order to analyze the associated variables.

ResultsDifferences in attitudes towards gender-based violence were observed according to sex, age and attitudes in line with the feminist movement. Regarding the linear regression model, the results showed that the FWMS is a predictor of GEPGVS, as well as sex.

ConclusionsHolding attitudes in line with the feminist movement is a factor that may be promoted in order to increase the awareness of gender-based violence.

Determinar las actitudes hacia la igualdad y la sensibilización en cuanto a la violencia de género, y analizar las variables asociadas a una mayor sensibilización sobre la violencia de género de los estudiantes de ciencias de la salud y trabajo social.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal. La muestra consistió en 437 estudiantes de los grados de ciencias de la salud y trabajo social de la Universidad de Zaragoza (España) durante 2018 y 2019. Las variables del estudio fueron variables sociodemográficas, variables académicas, actitudes hacia el movimiento feminista usando la Feminism and the women's movement scale (FWMS) y actitudes hacia la violencia de género mediante la Escala sobre Igualdad y Prevención de la Violencia de Género (EIPVG). Se realizaron un estudio correlacional y una regresión lineal múltiple para conocer las variables asociadas a una mayor sensibilización.

ResultadosSe observaron diferencias en las actitudes hacia la violencia de género en función del sexo, la edad y las actitudes favorables al movimiento feminista. Con respecto al modelo de regresión lineal, los resultados mostraron que la FWMS es un predictor de la EIPVG, así como el sexo.

ConclusionesLas actitudes favorables al movimiento feminista son un factor que puede promoverse para incrementar la sensibilización sobre la violencia de género.

Gender-based violence against women is currently a major public health problem.1 Thirty five percent of all women across the globe have at one point been victims of physical and/or sexual violence by people other than their partner and 38% of all female homicides are due to conjugal violence.2 Women suffering from gender-based violence may reveal physical, psychological, behavioral, sexual and reproductive consequences.3

As for health care professionals, clearly the medical-healthcare and social care fields are prime sites for the detection and consideration of this problem.4 This is the case since often, these consultations are the only place where victims have contact with the outside world, providing them with the opportunity to discuss intimate matters related to their health and sexuality in a confidential manner.5 Furthermore, it has been seen that women who are victims of gender-based violence tend to visit health services more frequently.6

Given that the effects of gender-based violence on women's health exists at several levels, it appears logical that an interdisciplinary approach to this problem would be ideal.5 Hence, the comprehensive care model governing the European National Health System plays a significant role. Thus, health service workers must be trained to provide care collaboratively, from the different disciplines such as medical, nursing, social work, psychology, etc., seeking the already highlighted necessary actions to assist women so as to reduce the existing inequalities, focusing on a person-centered care.7 In Spain, it is regulated by Organic Law 1/2004, of 28 December on Integrated Protection Measures against Gender Violence.8 The detection of gender-based violence cases by healthcare professionals is fundamental, thus it will lead to the breaking of silence, which is the first step in the understanding and visualization of the problem.6

There has been an attempt to introduce certain controversial measures of systematic inquiry, but there has not been sufficient scientific evidence to justify their realization.9 So, the recommended attitude to be taken by the healthcare professional, as recommended by the Spanish Family and Community Medicine Society, consists of actively listening and empathizing, being receptive to detect, evaluate and act upon any indication of violence and the effects that it may have caused.10

A 2016 study on several primary care centers in Spain revealed that two thirds of the participating Primary Care staff reported having asked questions about intimate partner violence during the preceding 6 months, taking relevant actions in those cases that so required.10,11 It was also found that asking questions about gender-based violence increased considerably in the case of professionals who felt that they were well trained on this subject and who were provided with a protocol that would guide them in handling the cases. Thus, the potential hypothesis arising suggests that the effectiveness of specific protocols to detect and intervene in cases of gender-based violence depends, at least to some extent, on the existence of adequate training for health professionals, which justifies the need for specific training on issues of gender-based violence in these professionals.11

As for gender-based violence training, consensus exists as to the need to educate healthcare professionals on the topic of gender-based violence.12,13 Several works have shown greater student comfort when required to ask patients about gender-based violence and initiate management in the necessary cases.14 All of this led to the creation, in the 1990s, of the hypothesis that gender-based violence education could have a positive impact on the behavior of healthcare professionals, which in turn supported the inclusion of training in this subject in the medical degree curriculum.14 Some studies have proposed teaching and curricular tools to achieve an increased awareness in university medical students.15 This has been confirmed by recent studies, which while comparing opinions, knowledge and training on gender-based violence in students from other countries, found that the participants, who received more education related to this topic, knew more about the issue and considered it to be a major problem. Findings such as these seem to suggest that this training could improve not only the students’ knowledge, but also their level of sensitization and awareness.16

Regarding the gender-based violence education received by nursing students, different studies have concluded that, the more training received in this sense, the more willing they are to identify cases of gender-based violence.17 Thus, it has been recommended that this training be initiated at the university stage and be continued upon completion of this stage.18 However, a literature review has concluded that the current university curriculum does not prepare Nursing students to attend to victims of gender-based violence, while at the same time, reveals that subsequent education is limited.18

Social workers play a very important role in the supporting task of women who are in a situation of abuse and/or are victims of sexist violence. However, a review of the curriculum of 35 Spanish universities offering the social work degree shows that only 21 of these universities offer subjects that addressed Social Work in the context of gender and/or gender-based violence.19

Although there are training programs on gender-based violence that aim to improve the health professionalś capacity to manage and care for victims,20 few studies have analyzed the current situation of students in terms of their perceptions as to the training received, the barriers and facilitating factors that they identify for the application of a feminist, equality and prevention-based approach to gender-based violence. This study also analyzes alignment with feminist ideas as a factor that is relevant to awareness of gender-based violence in both the healthcare sector21 as well as in other groups of society.22,23

The objective of this study was to determine the attitudes towards the feminist movement, equality and prevention of gender-based violence of students of the health sciences (medicine, nursing and physiotherapy) and social work degrees at the University of Zaragoza (Spain), and to analyze the variables associated with a higher awareness of gender-based violence.

MethodA cross-sectional descriptive study was designed to determine the characteristics of the target population and their attitudes toward the feminist movement and gender-based violence. The population consisted of students of the health sciences (medicine, nursing and physiotherapy) and social work degrees at the University of Zaragoza (Spain) during 2018 and 2019. The study sample included all of the individuals who answered the data collection questionnaire. A total of 2911 subjects were enrolled in these degrees,24 25.21% of which are male and 74.79% female, distributed as follows: 45.65% enrolled in the medicine degree, 21.26% in nursing, 8.55% in physiotherapy and 24.53% in social work. Given the population size of 2911 subjects, assuming an error of 5% and a probability of success of 95%, with a confidence level of 95% and a precision of 3%, it was necessary for at least 190 students to participate in the study.

A data collection book was prepared, including the following variables:

- •

Socio-demographic variables: sex (male/female), age and type of habitual residence (rural/urban), degree (medicine, nursing, physiotherapy or social work) and course.

- •

Feminism attitudes towards women's movement. The questionnaire Feminism and the women's movement scale25 (FWMS) was used, which assesses the level of alignment with the feminist movement. It consists of 10 items in which the subject must choose a score from 1 to 5, in a Likert-like format (with 1 representing “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). With a higher score (minimum 10, maximum 50), the individual is considered to be closer to the ideas of feminism.

- •

Attitudes on gender-based violence: for this, the Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender-based Violence Scale26 (GEPGVS) was used, which has been previously used to study attitudes of university students regarding gender-based violence. This scale consists of 28 items with a Likert-scale response, with scores from 1 to 5 for each of the items (with 1 also representing “strongly disagree” and 5 “strongly agree”). In this case, a lower score (minimum 28, maximum 140) implies a greater awareness.

- •

Training received throughout the degree in topics of feminism, equality and/or gender-based violence, coded dichotomously (yes/no) and as: no training; training in feminism and equality; in gender-based violence; in feminism+equality+gender-based violence. In the case of having received previous training on feminism, equality and/or gender-based violence, a question regarding the sufficiency of the same was posed. The answer was coded as: not sufficient; sufficient training in feminism and equality; in gender-based violence; in feminism+equality+gender-based violence.

- •

Subjective importance of training in topics of feminism, equality and/or gender-based violence, as: no importance; importance of training in feminism and equality; importance of training in gender-based violence; importance of training in feminism+equality+gender-based violence. This variable was collected through the following question: for the proper performance of the profession that you are studying, is it necessary to have knowledge of …? They were allowed to check all options having affirmative responses.

Once the questionnaire was prepared, it was disseminated to the study population through the Google Forms web application, in which the questionnaire was introduced to complete it. We contacted teachers and course delegates, making use of platforms such as the institutional mail of the University of Zaragoza, as well as delegation groups, class dissemination lists, etc. to request participation in the study and the link to the survey. The diffusion period lasted approximately 90 days. Once this period was over, a database was created based on all of the responses obtained.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (Spain) (19/065). All the data were collected anonymously. All of the participating subjects provided their informed consent prior to accessing the questionnaire, since prior to the questionnaire, a text approved by the Ethics Committee informed them of all aspects relevant to the study, indicating that if they began the questionnaire, it was considered that they understood and accepted participation in the study.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis was carried out of the characteristics of the study population related to the variables of the study. Since these variables did not follow a Gaussian distribution, as confirmed by the Shapiro Wilk test, other robust statistics have been indicated. An association study was conducted on attitudes towards gender-based violence, measured through the GEPGVS and the other variables. We studied the correlation between attitudes toward the feminist movement (FWMS) and attitudes towards gender-based violence (GEPGVS) and took a multivariate scales model to identify the strength of the association between the two. The independent variables were introduced in the regression model with a stepwise method with which we obtained a final model in which only significant variables have been included. Since the scales did not present a normal distribution, nonparametric tests were used (Mann-Whitney U for two different groups, Kruskal Wallis for more than two groups and Spearman's nonparametric Rho correlation for continuous variables (age, FWMS, GEPGVS).

The data from the questionnaires were analyzed statistically using the SPSS 21 statistical package. All levels of significance were established at 0.05.

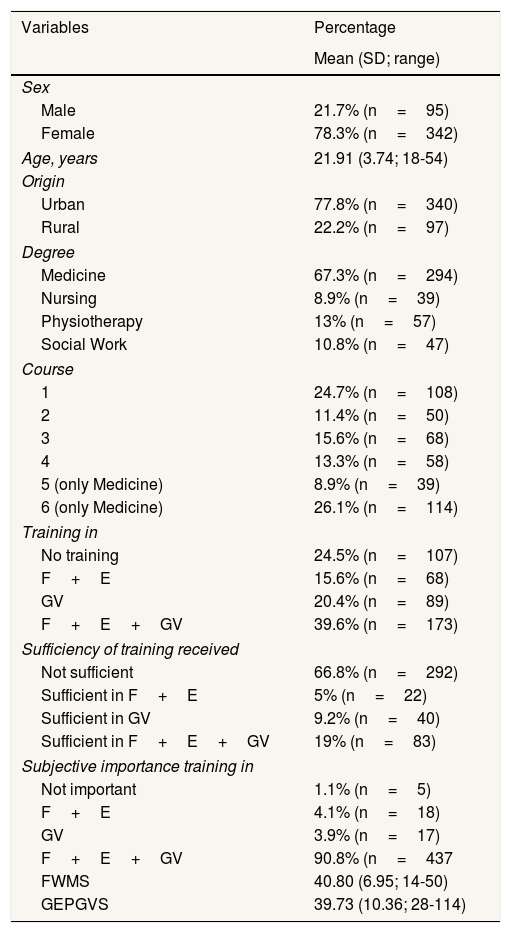

ResultsThe survey was answered by 437 people, meaning a response rate of 15.01% of the target population, with no significant differences in the distribution by gender between the sample and the target population (p=0.502). First, as shown in Table 1, a description of the sample has been offered in terms of the study variables collected. The typical participant profile is female, aged between 21 and 22 years and, of urban origin.

Description of the sample in study variables.

| Variables | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Mean (SD; range) | |

| Sex | |

| Male | 21.7% (n=95) |

| Female | 78.3% (n=342) |

| Age, years | 21.91 (3.74; 18-54) |

| Origin | |

| Urban | 77.8% (n=340) |

| Rural | 22.2% (n=97) |

| Degree | |

| Medicine | 67.3% (n=294) |

| Nursing | 8.9% (n=39) |

| Physiotherapy | 13% (n=57) |

| Social Work | 10.8% (n=47) |

| Course | |

| 1 | 24.7% (n=108) |

| 2 | 11.4% (n=50) |

| 3 | 15.6% (n=68) |

| 4 | 13.3% (n=58) |

| 5 (only Medicine) | 8.9% (n=39) |

| 6 (only Medicine) | 26.1% (n=114) |

| Training in | |

| No training | 24.5% (n=107) |

| F+E | 15.6% (n=68) |

| GV | 20.4% (n=89) |

| F+E+GV | 39.6% (n=173) |

| Sufficiency of training received | |

| Not sufficient | 66.8% (n=292) |

| Sufficient in F+E | 5% (n=22) |

| Sufficient in GV | 9.2% (n=40) |

| Sufficient in F+E+GV | 19% (n=83) |

| Subjective importance training in | |

| Not important | 1.1% (n=5) |

| F+E | 4.1% (n=18) |

| GV | 3.9% (n=17) |

| F+E+GV | 90.8% (n=437 |

| FWMS | 40.80 (6.95; 14-50) |

| GEPGVS | 39.73 (10.36; 28-114) |

F+E: feminism and equality; F+E+VG: feminism, equality, gender-based violence; FWMS: Feminism and the Women's Movement Scale; GEPGVS: Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender-based Violence Scale; SD: standard deviation; VG: gender-based violence.

Regarding previous training in topics of feminism, equality and/or gender-based violence, 75.5% confirmed having received training. 98.9% of the participants consider that training in at least one of these areas is important for later performance in the work for which they are preparing. Specifically, 76.9% of respondents consider training in the three fields to be important. As for the existence of training on these issues in the considered degree courses, 41.0% of students refer to a complete absence of the same, therefore leaving 59.0% of students who refer to the existence of training in at least one of these fields in their degree studies. When asked if they consider this training to be sufficient, 66.8% responded negatively, suggesting that the education received is not satisfactory. 90.8% of students consider that training in feminism, equality and gender-based violence is important.

The average score obtained in the FWMS is of 40.80 (standar deviation [SD]: 6.95), which implies a high level of alignment with the ideas of the feminist movement (range between 10 and 50, with the higher the score, the greater the alignment with feminist ideas). The average score obtained in the GEPGVS is 39.73 (SD: 10.36), which also implies a high level of awareness of issues related to gender-based violence (range between 28 and 140, with a lower score suggesting greater awareness).

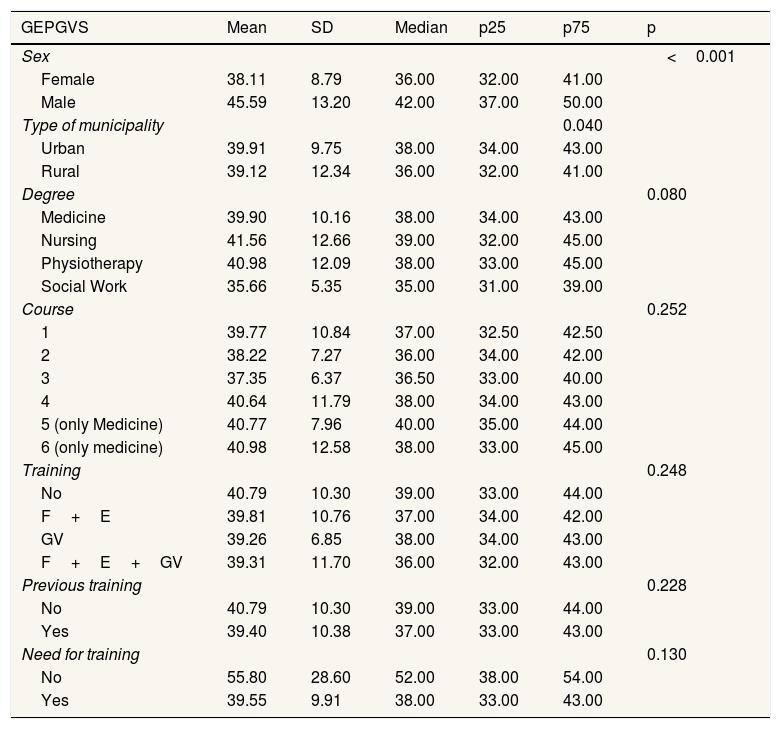

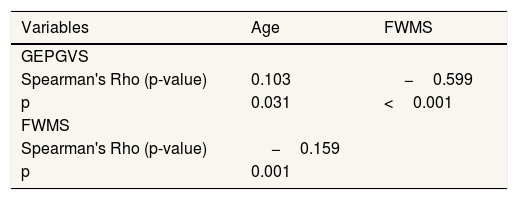

Differences in attitudes towards gender-based violence were observed according to sex and type of population. Specifically, women, coming from the urban environment were most sensitive to this topic, as it is shown in Table 2. A correlation was also observed between age and an increased awareness of gender-based violence, which was also found for attitudes according to with the feminist movement, as seen in Table 3. A higher FWMS score was also found for women, as compared to men (p=0.004).

Differences in awareness of gender-based violence based on gender, type of municipality, grade, course, training received and subjective perception of the need for training in these topics.

| GEPGVS | Mean | SD | Median | p25 | p75 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | <0.001 | |||||

| Female | 38.11 | 8.79 | 36.00 | 32.00 | 41.00 | |

| Male | 45.59 | 13.20 | 42.00 | 37.00 | 50.00 | |

| Type of municipality | 0.040 | |||||

| Urban | 39.91 | 9.75 | 38.00 | 34.00 | 43.00 | |

| Rural | 39.12 | 12.34 | 36.00 | 32.00 | 41.00 | |

| Degree | 0.080 | |||||

| Medicine | 39.90 | 10.16 | 38.00 | 34.00 | 43.00 | |

| Nursing | 41.56 | 12.66 | 39.00 | 32.00 | 45.00 | |

| Physiotherapy | 40.98 | 12.09 | 38.00 | 33.00 | 45.00 | |

| Social Work | 35.66 | 5.35 | 35.00 | 31.00 | 39.00 | |

| Course | 0.252 | |||||

| 1 | 39.77 | 10.84 | 37.00 | 32.50 | 42.50 | |

| 2 | 38.22 | 7.27 | 36.00 | 34.00 | 42.00 | |

| 3 | 37.35 | 6.37 | 36.50 | 33.00 | 40.00 | |

| 4 | 40.64 | 11.79 | 38.00 | 34.00 | 43.00 | |

| 5 (only Medicine) | 40.77 | 7.96 | 40.00 | 35.00 | 44.00 | |

| 6 (only medicine) | 40.98 | 12.58 | 38.00 | 33.00 | 45.00 | |

| Training | 0.248 | |||||

| No | 40.79 | 10.30 | 39.00 | 33.00 | 44.00 | |

| F+E | 39.81 | 10.76 | 37.00 | 34.00 | 42.00 | |

| GV | 39.26 | 6.85 | 38.00 | 34.00 | 43.00 | |

| F+E+GV | 39.31 | 11.70 | 36.00 | 32.00 | 43.00 | |

| Previous training | 0.228 | |||||

| No | 40.79 | 10.30 | 39.00 | 33.00 | 44.00 | |

| Yes | 39.40 | 10.38 | 37.00 | 33.00 | 43.00 | |

| Need for training | 0.130 | |||||

| No | 55.80 | 28.60 | 52.00 | 38.00 | 54.00 | |

| Yes | 39.55 | 9.91 | 38.00 | 33.00 | 43.00 |

F+E: feminism and equality; F+E+VG: feminism, equality, gender-based violence; FWMS: Feminism and the Women's Movement Scale; GEPGVS: Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender-based Violence Scale; SD: standard deviation; VG: gender-based violence.

Correlation among the awareness of gender-based violence and age and the level of alignment with the ideas of the feminist movement.

| Variables | Age | FWMS |

|---|---|---|

| GEPGVS | ||

| Spearman's Rho (p-value) | 0.103 | −0.599 |

| p | 0.031 | <0.001 |

| FWMS | ||

| Spearman's Rho (p-value) | −0.159 | |

| p | 0.001 |

FWMS: Feminism and the Women's Movement Scale; GEPGVS: Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender Violence Scale.

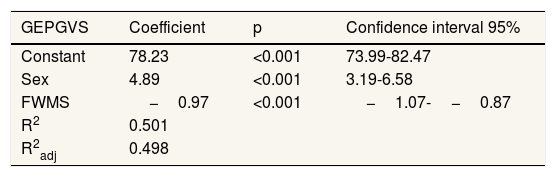

Regarding the linear regression model, the results are shown in Table 4, where it may be observed that the FWMS scale is a predictor of GEPGVS, as well as sex, such that women score almost 5 points (4.89) higher than men on the scale. As for the feminist ideas, for each point of the FWMS, the GEPGVS decreases by almost 1 point (−0.97). The model explains 50.10% of the variance.

Linear regression model in relation to the level of awareness regarding gender equality and gender-based violence.

| GEPGVS | Coefficient | p | Confidence interval 95% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 78.23 | <0.001 | 73.99-82.47 |

| Sex | 4.89 | <0.001 | 3.19-6.58 |

| FWMS | −0.97 | <0.001 | −1.07-−0.87 |

| R2 | 0.501 | ||

| R2adj | 0.498 |

FWMS: Feminism and the Women's Movement Scale; GEPGVS: Gender Equality and Prevention of Gender-based Violence Scale.

In this study, the variables that have been found to be significant, with respect to gender-based violence awareness (GEPGVS), both in bivariate and multi-variate analyses, were sex, age and alignment with the ideas of the feminist movement (FWMS). However, training, as received by students, was not found to be a variable that significantly improved awareness. In accordance with the greater proportional sensitization found in this study based on sex, this correlation also shows that women score five times higher in ideas related to the feminist movement, once again highlighting the importance of the inclusion of men in the curricular designs on training in feminism, equality and prevention of gender-based violence.7

In addition, and with regards to age, which has shown a correlation with the awareness of gender-based violence, and the relationship with the feminist movement, other works have found a relationship between socioeconomic situation, making young females with low economic status more vulnerable, finding that young people who neither study nor work and who have children at a younger age suffer more violence.27

The existence of positive attitudes and relationship or alignment with the ideas of the feminist movement has been observed, as well as a high level of positive attitudes on issues related to gender-based violence, as seen in other studies that also have highlighted the importance of feminist education.28,29 Once again, women appear to be more sensitive to these issues, but in this case nursing students stand out, as has been the case in other studies,30 although deficiencies and obstacles for effective sanitary responses have also been found in this professional group.31

Regards the training, the results of our study reveal a high percentage of students perceiving the need for training in topics related to feminism and gender-based violence, in line with other studies, specifically females and medical students,32 in our study as well as those aged from 21 to 22 years old and from urban environments.

Although the students taking part in the study consider that there is training in these subjects, a large proportion of them (70%) believe that it is insufficient. This data should lead to the development of research on the usefulness and applicability of the training programs in this area and both the designs and the content of the same should be evaluated.33,34 As different studies highlight, despite the legislative amendments introduced, the subjects and content on gender-based violence contemplated by the university curricula of the majority of undergraduate studies remain mostly elective and/or free choice.35 In addition, the impact of these educational interventions on the final patient situation remains unknown,12 suggesting new study challenges for the design of training activities, the transfer of knowledge and its application to healthcare practice.

The study has certain limitations, such as those typical of a transversal type design: the willingness to participate by the same, the low response rate (15.01%), but it exceeds the necessary sample size, and also, the limited participation of nursing and social work students. The difference in participation between the university degrees may be due to distinct implication of the course delegates or the quantity of surveys that the students had to respond to at the time of the study. Male student participation has also been lower, but without significant differences in terms of the percentage of the target population. The questionnaire was conducted online but this is not considered a limitation since this is a very common way for university students and people of these ages to complete surveys, including quality surveys, etc. Finally, the study's strengths should be highlighted, including its external validity, given the adequate sample size and internal validity, and given that the robust statistical indicators and replicability of the study.

ConclusionsBeing female, older and having attitudes in line with the feminist movement have been found to be factors associated with a greater awareness of gender-based violence by health sciences and social work students. Of these factors, attitudes in line with feminism may be promoted and could be a strategy used to increase awareness of gender-based violence, in order to improve its detection and handling.

Gender-based violence against women is currently a major public health problem. Medical-healthcare and social care fields are prime sites for the detection and consideration of this problem. Greater awareness and specific training for health and social professionals on gender issues are necessary for a better approach to this problem. This specific training is recommendable to be taught during undergraduate training. It is important to have validated instruments in relation to feminism, equality and gender-based violence issues.

What does this study add to the literature?To know the attitudes towards the feminist movement, equality and prevention of gender-based violence of university students of the degrees of health sciences (medicine, nursing and physiotherapy) and social work. To know the training that university students of health sciences (medicine, nursing and physiotherapy) and social work receive. To analyze the variables that are related to greater awareness of gender-based violence.

María Teresa Ruiz Cantero.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsConceptualization: M. Berbegal-Bolsas and R. Magallón-Botaya. Data curation: M. Berbegal-Bolsas. Formal analysis: M. Berbegal-Bolsas and B. Oliván-Blázquez. Writing original draft: M. Berbegal-Bolsas, A. Gasch-Gallén and B. Oliván-Blázquez. Writing review and editing: all authors.

We wish to thank the Research Group B21_R17 of the Department of Research, Innovation and University of the Government of Aragon (Spain), and Feder Funds “Another way to make Europe” for their support in the development of the study.