To determine if the onset of the economic crisis in Spain affected cancer mortality and mortality trends.

MethodWe conducted a longitudinal ecological study based on all cancer-related deaths and on specific types of cancer (lung, colon, breast and prostate) in Spain between 2000 and 2013. We computed age-standardised mortality rates in men and women, and fit mixed Poisson models to analyse the effect of the crisis on cancer mortality and trends therein.

ResultsAfter the onset of the economic crisis, cancer mortality continued to decline, but with a significant slowing of the yearly rate of decline (men: RR = 0.987, 95%CI = 0.985-0.990, before the crisis, and RR = 0.993, 95%CI = 0.991-0.996, afterwards; women: RR = 0.990, 95%CI = 0.988-0.993, before, and RR = 1.002, 95%CI = 0.998-1.006, afterwards). In men, lung cancer mortality was reduced, continuing the trend observed in the pre-crisis period; the trend in colon cancer mortality did not change significantly and continued to increase; and the yearly decline in prostate cancer mortality slowed significantly. In women, lung cancer mortality continued to increase each year, as before the crisis; colon cancer continued to decease; and the previous yearly downward trend in breast cancer mortality slowed down following the onset of the crisis.

ConclusionsSince the onset of the economic crisis in Spain the rate of decline in cancer mortality has slowed significantly, and this situation could be exacerbated by the current austerity measures in healthcare.

Determinar si el inicio de la crisis económica en España afectó a la mortalidad por cáncer y sus tendencias.

MétodoEstudio ecológico longitudinal que analiza todas las muertes por cáncer y por tipos específicos de cáncer (pulmón, colon, mama y próstata) en España entre 2000 y 2013. Se estimaron las tasas de mortalidad estandarizadas por edad en hombres y mujeres, y se ajustaron modelos mixtos de Poisson para analizar el efecto de la crisis sobre la mortalidad por cáncer y sus tendencias.

ResultadosDespués del inicio de la crisis económica, la mortalidad por cáncer continuó su tendencia a la baja, pero con una disminución significativa del decrecimiento anual (hombres: riesgo relativo [RR] = 0,987, intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%] = 0,985-0,990, antes de la crisis, y RR = 0,993, IC95% = 0,991-0,996 después; mujeres: RR = 0,990, IC95% = 0,988-0,993, antes, y RR = 1,002, IC95% = 0,998-1,006 después). En los hombres, la mortalidad por cáncer de pulmón se redujo, continuando la tendencia observada en el periodo anterior a la crisis; la tendencia en la mortalidad por cáncer de colon no cambió significativamente y siguió aumentando; y la disminución anual de la mortalidad por cáncer de próstata se desaceleró significativamente. En las mujeres, la mortalidad por cáncer de pulmón continuó aumentando cada año, como antes de la crisis; el cáncer de colon continuó disminuyendo; y la tendencia a la disminución de la mortalidad por cáncer de mama se desaceleró después del inicio de la crisis.

ConclusionesDesde el inicio de la crisis económica en España, la disminución de la tasa de mortalidad por cáncer se ha desacelerado significativamente y esta situación podría verse exacerbada por las actuales medidas de austeridad en el sistema sanitario.

The impact of an economic crisis on health depends on various factors.1,2 While economic crises have adverse effects on both the determinants and inequalities of health,3,4 they can in fact provide an opportunity to promote primary prevention healthcare measures.5

History has already shown that economic crises can be accompanied by an increase in mortality, particularly among certain population subgroups, such as children.6,7 Within the European Union for instance, a reduction in public spending on healthcare during times of crisis has been found to be associated with increased mortality.8 Interestingly, some studies have not observed an increase in overall mortality, but rather an increase in the number of suicides,9–11 offset by a decrease in other causes of death, such as those due to traffic injuries.12,13

Increased unemployment along with lower investment in the public health sector are known to be associated with an increase in total cancer mortality, particularly of breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer.14–18 Furthermore, it has been shown in some countries that complete public health coverage or greater public health expenditure counteract the negative effect of unemployment, and thus these countries do not show an increase in cancer mortality.15,19,20

The most recent economic crisis began to affect Spain in 2008, and a recent study analysed the effect that this crisis had on both general mortality and some specific causes.21 This study found that overall mortality was declining before the onset of the crisis (2004-2007), and that the same trend continued during the subsequent years (2008-2011), particularly among disadvantaged socioeconomic groups. These two periods also saw a lower number of cancer-related deaths, especially in men, although this study only analysed data until 2011, and did not distinguish between the different types of cancer.

In response to the 2008 crisis in Spain, the Spanish government activated various economic adjustment procedures, including healthcare reform encompassing a set of legislative measures aimed at cutting health expenditure. This reform, brought into action by the approval of Royal Decree Law 16/2012, was a key health austerity measure.7,22,23 However, the effect of the economic crisis in Spain has been heterogeneous with respect to the different autonomous communities, which may be because each region has some control over how social cuts are implemented.24

Given the limited research on economic crises and cancer mortality, the objective of our study was to determine if cancer mortality, and its overall trends, have changed since the onset of the latest economic crisis in Spain.

MethodsWe conducted a longitudinal study of the period 2000 to 2013, with 2008 considered as the year the economic crisis started, and the study population consisted of all residents in Spain during 2000 to 2013. We collected information from the Spanish Mortality Registry, a resource based on the Statistical Bulletin of Deaths, and from the ongoing population census. We analysed all deaths caused by cancer in general (CIE-10: C00-C96), as well as those caused by four specific types of malignant neoplasm: colon (CIE-10: C18), bronchus and lung (CIE-10: C34), breast (CIE-10: C50), and prostate (CIE-10: C61). For our analysis, we considered the following variables: year of death, age at death, gender, autonomous community, and cause of death.

We performed a descriptive analysis of the population according to the number of deaths caused by each of the types of cancer in men and women for each year of the study period. We then estimated annual mortality rates for all cancers, individually for lung and colon cancer in both sexes, for prostate in men, and for breast cancer in women. Rates were standardised by age using the direct method in which the reference population was the Spanish population of 2001. Data were also represented graphically to visibly highlight the trends.

Finally, we constructed mixed Poisson models to analyse the effect of the crisis on mortality, including its general trends both before and during the crisis (see Model 1; where I = autonomous community, and t = year). We accounted for the variability between autonomous communities by including random effects in the constant and coefficients of the variables for crisis (dichotomous variable taking value 0 for 2000-2007, and 1 for 2008-2013) (b1i), year (b2i), and the interaction between crisis and year (b3i). Using our model, we determined the relative risk (RR) for each type of cancer by estimating the differences in mortality between the first year of the crisis (2008) and the last year before the onset of the crisis (2007; RR crisis; 95%CI). Finally, to evaluate annual trends in mortality, we determined the relative risks for the pre-crisis (RR pre-crisis years; 95%CI) and crisis (RR crisis years; 95%CI) periods.

Model 1:

deathit ∼ Poisson(λit), i = 1,…,17, t = 1,…,14

log(λit) = log(popit) + (β0 + b0i) + (β1 + b1i)*crisist + (β2 + b2i)*(yeart-2008) + (β3 + b3i)*crisist*(yeart-2008) + ɛit

where:

b0i ∼ N(0,σ02), b1i ∼ N(0,σ12), b2i ∼ N(0,σ22), b3i ∼ N(0,σ32)

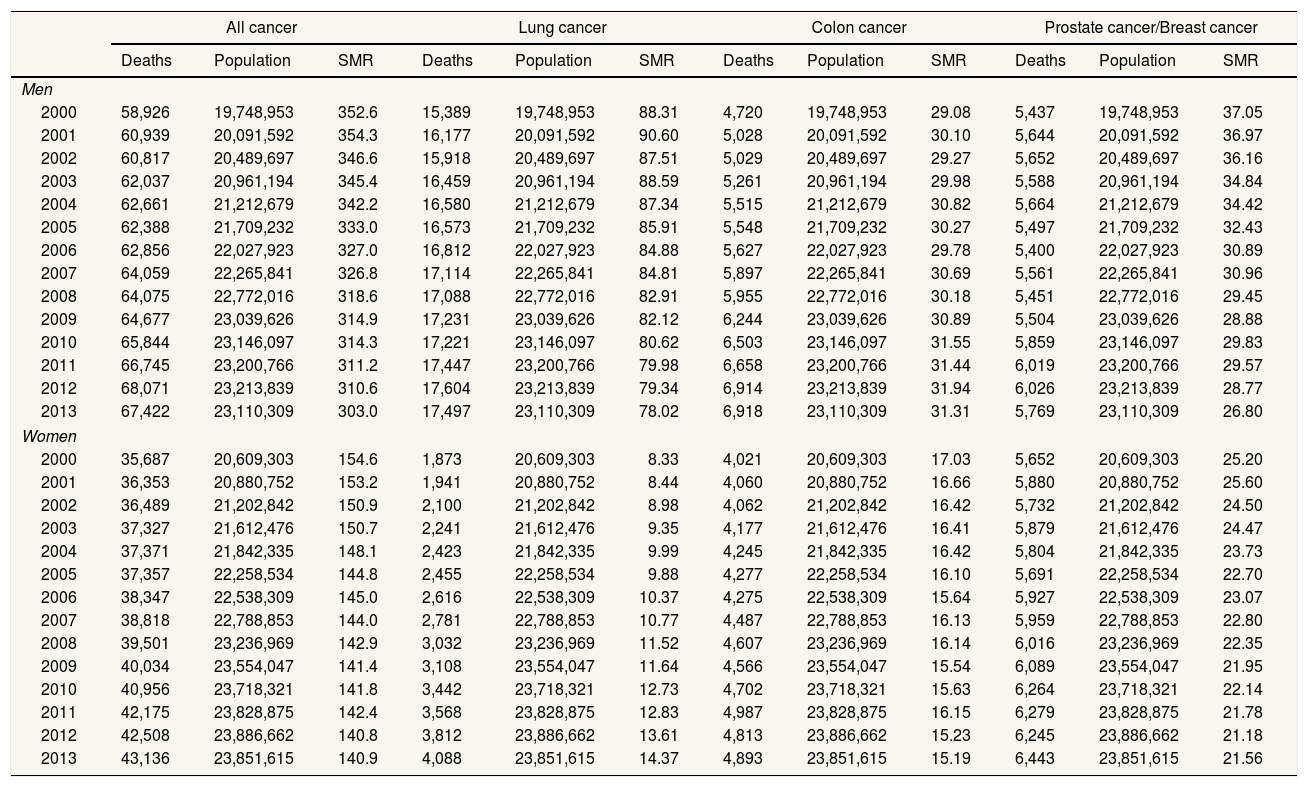

ResultsTable 1 shows the number of cancer-related deaths in Spain in the years 2000 to 2013, overall, and for lung, colon, prostate and breast cancer. Overall, the data show higher cancer mortality in men than women, with lung and breast cancer being the principal causes of cancer mortality in men and women, respectively.

Number of deaths due to cancer, total population in Spain and standardised mortality rate (SMR) per 100,000 inhabitants. Men and women, 2000-2013 (Source: Spanish Mortality Registry, Spanish Institute of Statistics).

| All cancer | Lung cancer | Colon cancer | Prostate cancer/Breast cancer | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | Population | SMR | Deaths | Population | SMR | Deaths | Population | SMR | Deaths | Population | SMR | |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| 2000 | 58,926 | 19,748,953 | 352.6 | 15,389 | 19,748,953 | 88.31 | 4,720 | 19,748,953 | 29.08 | 5,437 | 19,748,953 | 37.05 |

| 2001 | 60,939 | 20,091,592 | 354.3 | 16,177 | 20,091,592 | 90.60 | 5,028 | 20,091,592 | 30.10 | 5,644 | 20,091,592 | 36.97 |

| 2002 | 60,817 | 20,489,697 | 346.6 | 15,918 | 20,489,697 | 87.51 | 5,029 | 20,489,697 | 29.27 | 5,652 | 20,489,697 | 36.16 |

| 2003 | 62,037 | 20,961,194 | 345.4 | 16,459 | 20,961,194 | 88.59 | 5,261 | 20,961,194 | 29.98 | 5,588 | 20,961,194 | 34.84 |

| 2004 | 62,661 | 21,212,679 | 342.2 | 16,580 | 21,212,679 | 87.34 | 5,515 | 21,212,679 | 30.82 | 5,664 | 21,212,679 | 34.42 |

| 2005 | 62,388 | 21,709,232 | 333.0 | 16,573 | 21,709,232 | 85.91 | 5,548 | 21,709,232 | 30.27 | 5,497 | 21,709,232 | 32.43 |

| 2006 | 62,856 | 22,027,923 | 327.0 | 16,812 | 22,027,923 | 84.88 | 5,627 | 22,027,923 | 29.78 | 5,400 | 22,027,923 | 30.89 |

| 2007 | 64,059 | 22,265,841 | 326.8 | 17,114 | 22,265,841 | 84.81 | 5,897 | 22,265,841 | 30.69 | 5,561 | 22,265,841 | 30.96 |

| 2008 | 64,075 | 22,772,016 | 318.6 | 17,088 | 22,772,016 | 82.91 | 5,955 | 22,772,016 | 30.18 | 5,451 | 22,772,016 | 29.45 |

| 2009 | 64,677 | 23,039,626 | 314.9 | 17,231 | 23,039,626 | 82.12 | 6,244 | 23,039,626 | 30.89 | 5,504 | 23,039,626 | 28.88 |

| 2010 | 65,844 | 23,146,097 | 314.3 | 17,221 | 23,146,097 | 80.62 | 6,503 | 23,146,097 | 31.55 | 5,859 | 23,146,097 | 29.83 |

| 2011 | 66,745 | 23,200,766 | 311.2 | 17,447 | 23,200,766 | 79.98 | 6,658 | 23,200,766 | 31.44 | 6,019 | 23,200,766 | 29.57 |

| 2012 | 68,071 | 23,213,839 | 310.6 | 17,604 | 23,213,839 | 79.34 | 6,914 | 23,213,839 | 31.94 | 6,026 | 23,213,839 | 28.77 |

| 2013 | 67,422 | 23,110,309 | 303.0 | 17,497 | 23,110,309 | 78.02 | 6,918 | 23,110,309 | 31.31 | 5,769 | 23,110,309 | 26.80 |

| Women | ||||||||||||

| 2000 | 35,687 | 20,609,303 | 154.6 | 1,873 | 20,609,303 | 8.33 | 4,021 | 20,609,303 | 17.03 | 5,652 | 20,609,303 | 25.20 |

| 2001 | 36,353 | 20,880,752 | 153.2 | 1,941 | 20,880,752 | 8.44 | 4,060 | 20,880,752 | 16.66 | 5,880 | 20,880,752 | 25.60 |

| 2002 | 36,489 | 21,202,842 | 150.9 | 2,100 | 21,202,842 | 8.98 | 4,062 | 21,202,842 | 16.42 | 5,732 | 21,202,842 | 24.50 |

| 2003 | 37,327 | 21,612,476 | 150.7 | 2,241 | 21,612,476 | 9.35 | 4,177 | 21,612,476 | 16.41 | 5,879 | 21,612,476 | 24.47 |

| 2004 | 37,371 | 21,842,335 | 148.1 | 2,423 | 21,842,335 | 9.99 | 4,245 | 21,842,335 | 16.42 | 5,804 | 21,842,335 | 23.73 |

| 2005 | 37,357 | 22,258,534 | 144.8 | 2,455 | 22,258,534 | 9.88 | 4,277 | 22,258,534 | 16.10 | 5,691 | 22,258,534 | 22.70 |

| 2006 | 38,347 | 22,538,309 | 145.0 | 2,616 | 22,538,309 | 10.37 | 4,275 | 22,538,309 | 15.64 | 5,927 | 22,538,309 | 23.07 |

| 2007 | 38,818 | 22,788,853 | 144.0 | 2,781 | 22,788,853 | 10.77 | 4,487 | 22,788,853 | 16.13 | 5,959 | 22,788,853 | 22.80 |

| 2008 | 39,501 | 23,236,969 | 142.9 | 3,032 | 23,236,969 | 11.52 | 4,607 | 23,236,969 | 16.14 | 6,016 | 23,236,969 | 22.35 |

| 2009 | 40,034 | 23,554,047 | 141.4 | 3,108 | 23,554,047 | 11.64 | 4,566 | 23,554,047 | 15.54 | 6,089 | 23,554,047 | 21.95 |

| 2010 | 40,956 | 23,718,321 | 141.8 | 3,442 | 23,718,321 | 12.73 | 4,702 | 23,718,321 | 15.63 | 6,264 | 23,718,321 | 22.14 |

| 2011 | 42,175 | 23,828,875 | 142.4 | 3,568 | 23,828,875 | 12.83 | 4,987 | 23,828,875 | 16.15 | 6,279 | 23,828,875 | 21.78 |

| 2012 | 42,508 | 23,886,662 | 140.8 | 3,812 | 23,886,662 | 13.61 | 4,813 | 23,886,662 | 15.23 | 6,245 | 23,886,662 | 21.18 |

| 2013 | 43,136 | 23,851,615 | 140.9 | 4,088 | 23,851,615 | 14.37 | 4,893 | 23,851,615 | 15.19 | 6,443 | 23,851,615 | 21.56 |

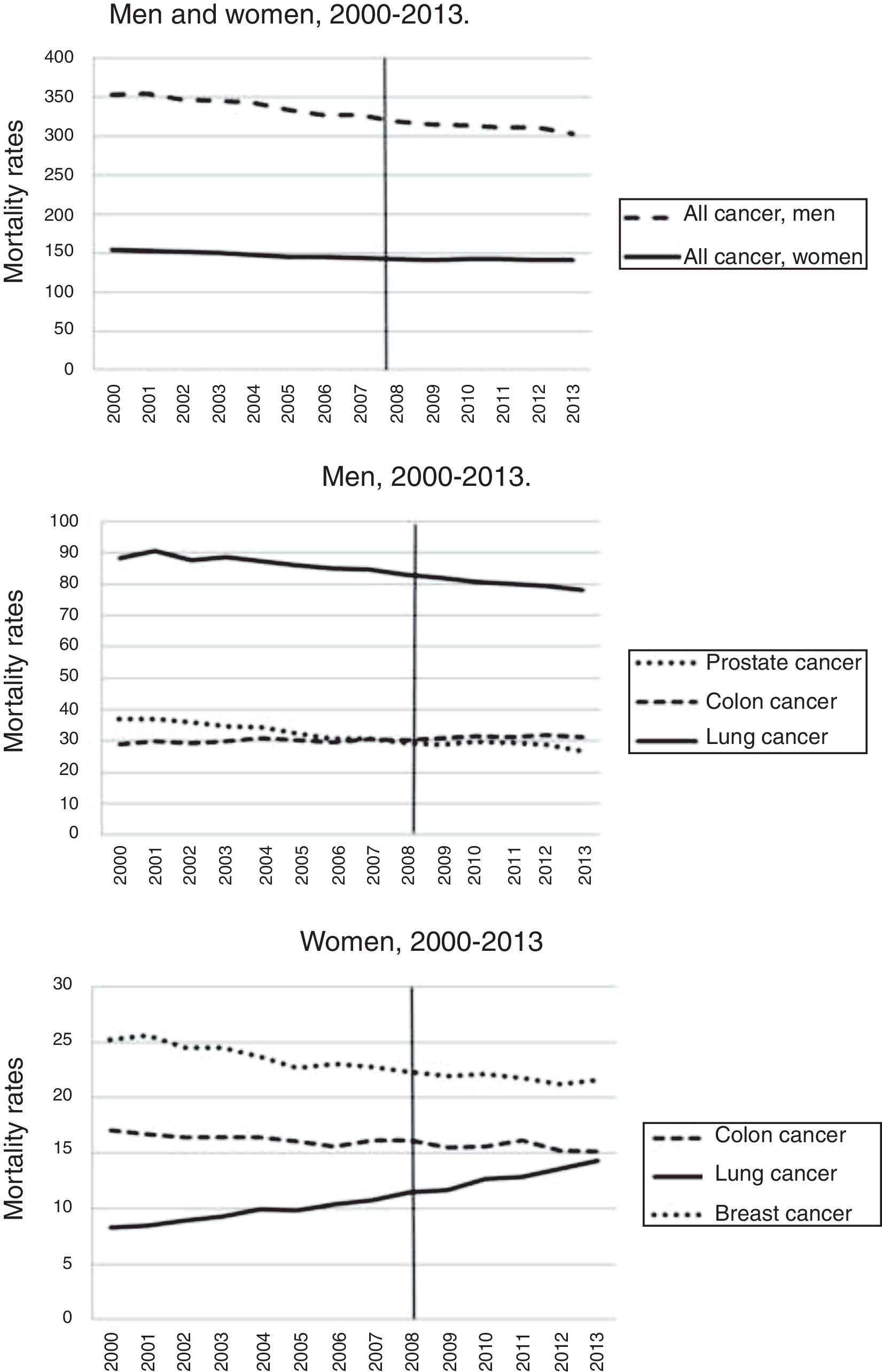

Between 2000 and 2013, cancer mortality as a whole decreased, especially in men (Fig. 1). However, we observe an upward trend in the most common cancer types, especially colon cancer in men, and lung cancer in women.

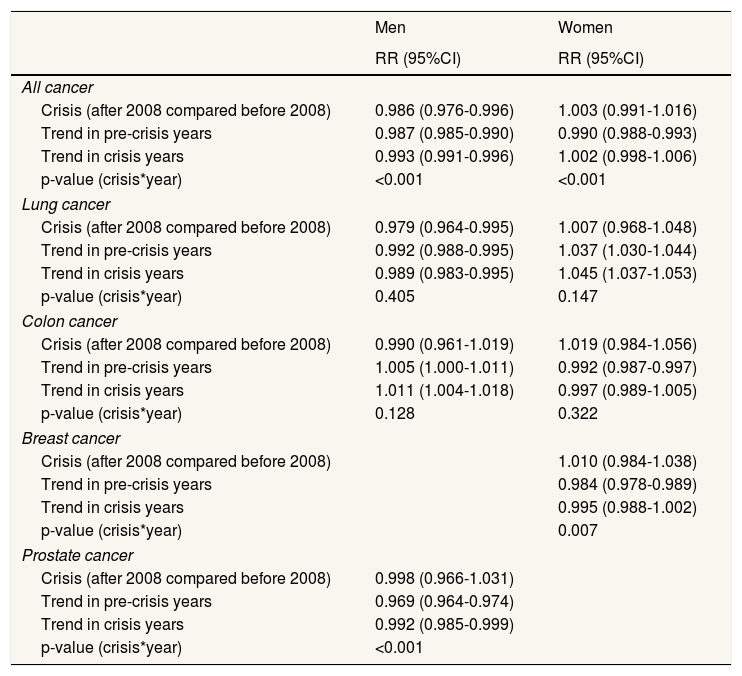

According to our model (Table 2), mortality decreased in men following the onset of the crisis (RR = 0.986; 95%CI = 0.976-0.996), although the rate of decline was slower (pre-crisis period, RR = 0.987; crisis period, RR = 0.993; p <0.001). Among women, the positive decline in mortality before the crisis (RR = 0.990; 95%CI = 0.988-0.993) was disrupted by the onset of the crisis (RR = 1.002; 95%CI = 0.998-1.006; p <0.001), such that there is now no statistically significant difference between mortality before and since the onset of the crisis.

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for cancer mortality. Men and women, Spain, 2000-2013. Source: Spanish Mortality Registry, Spanish Institute of Statistics.

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| RR (95%CI) | RR (95%CI) | |

| All cancer | ||

| Crisis (after 2008 compared before 2008) | 0.986 (0.976-0.996) | 1.003 (0.991-1.016) |

| Trend in pre-crisis years | 0.987 (0.985-0.990) | 0.990 (0.988-0.993) |

| Trend in crisis years | 0.993 (0.991-0.996) | 1.002 (0.998-1.006) |

| p-value (crisis*year) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Lung cancer | ||

| Crisis (after 2008 compared before 2008) | 0.979 (0.964-0.995) | 1.007 (0.968-1.048) |

| Trend in pre-crisis years | 0.992 (0.988-0.995) | 1.037 (1.030-1.044) |

| Trend in crisis years | 0.989 (0.983-0.995) | 1.045 (1.037-1.053) |

| p-value (crisis*year) | 0.405 | 0.147 |

| Colon cancer | ||

| Crisis (after 2008 compared before 2008) | 0.990 (0.961-1.019) | 1.019 (0.984-1.056) |

| Trend in pre-crisis years | 1.005 (1.000-1.011) | 0.992 (0.987-0.997) |

| Trend in crisis years | 1.011 (1.004-1.018) | 0.997 (0.989-1.005) |

| p-value (crisis*year) | 0.128 | 0.322 |

| Breast cancer | ||

| Crisis (after 2008 compared before 2008) | 1.010 (0.984-1.038) | |

| Trend in pre-crisis years | 0.984 (0.978-0.989) | |

| Trend in crisis years | 0.995 (0.988-1.002) | |

| p-value (crisis*year) | 0.007 | |

| Prostate cancer | ||

| Crisis (after 2008 compared before 2008) | 0.998 (0.966-1.031) | |

| Trend in pre-crisis years | 0.969 (0.964-0.974) | |

| Trend in crisis years | 0.992 (0.985-0.999) | |

| p-value (crisis*year) | <0.001 | |

RR for cancer mortality with respect to the effect of the crisis (mortality after the year 2008 compared to mortality before 2008), and RRs associated with the trends before and during the crisis (increase in annual mortality during the pre-crisis [2000-2008] and crisis [2008-2013] periods). Significant differences between the two trends are represented using p-values (interaction between year and crisis).

Regarding mortality due to specific types of cancer in men, lung cancer mortality decreased with the onset of the crisis (RR = 0.979; 95%CI = 0.964-0.995), but without a significant change in the general trend. In contrast, colon cancer mortality did not undergo any significant change after the start of the crisis, and continued to follow the same gradual increasing trend that had been observed during the pre-crisis period. Prostate cancer mortality did not vary markedly with the onset of the crisis, as the downward trend observed before the crisis underwent a significant regression (pre-crisis trend, RR = 0.969; crisis trend, RR = 0.992; p < 0.001).

In women, mortality due to lung cancer increased annually before the crisis (RR = 1.037; 95%CI = 1.030-1.044), and this trend continued after the start of the crisis. Similarly, the decreasing death trend in mortality due to colon cancer observed before the crisis also continued into the crisis period. In contrast, the decline in breast cancer mortality observed before the crisis has stagnated since 2008, (pre-crisis trend, RR = 0.984; crisis trend, RR = 0.995; p = 0.007).

DiscussionCancer mortality as a whole has continued to decrease since the onset of the crisis, especially in men, although this decrease has slowed since 2008. However, this has not been the case for all types of cancer, such as colon cancer, for which the number of deaths has increased, particularly since the onset of the crisis. In women, the decline in cancer-related deaths overall has slowed down since the start of the crisis, while those due to lung cancer continue to rise.

Our results are consistent with a previous report on overall cancer mortality in Spain during the 2004-2011 period,21 but encompass a larger time frame (2000-2013) and include an evaluation of specific cancers with higher mortality rates.

The trends observed in Spain are similar to those reported in Greece, where cancer mortality has continued to decline since the onset of the crisis.19 One of the reasons for this continued decline is that the Greek public health system continued to function effectively despite cuts imposed by the government in response to the crisis. Although there are some differences between the Greek and Spanish health systems, they are both public systems25 that provide full access to healthcare services and thereby buffer the influence of unemployment and reduced healthcare expenditure on increased cancer mortality during times of crisis.15 In Spain, however, there was a change in this trend −the rate of decline in cancer mortality decreased with the onset of the crisis.

The health reform introduced by Royal Decree Law 16/2012 could lead to the dismantling of the current public health system. This reform had many consequences, including a decrease in the number of available hospital beds, a reduction in emergency services hours, closure of certain medical services, cancellation of surgical operations, longer waiting lists, privatization of health services, and poorer access to the health system and pharmaceutical assistance.22,23,26–30 Between 2009 and 2013 public health expenditure in Spain decreased by 18.2%, which had a strong impact on the health system's equity and universality.31,32

A recent study has highlighted how austerity measures negatively affect the quality of healthcare and population health,33 and cancer patients in particular are routinely confronted with various economic burdens, such as co-payment for pharmacological treatments and non-urgent medical transport, and payment for orthopaedic prostheses and dietary products. These pressures may drive patients in a precarious economic situation to interrupt their medical treatment.34,35

According to medical oncologists,36 lung cancer is one of the tumours most affected by cutbacks in healthcare, which results in lower patient survival rate.37 In countries whose healthcare system has been severely affected by the crisis, the situation for lung cancer patients has worsened,38 which should be cause for serious reflection given the increasing prevalence of lung cancer among women in Spain.

According to a survey among cancer patients,39 the care they receive has been markedly affected by the crisis, including restrictions on innovative cancer therapies, increases waiting times, and failures to implement and continue early cancer screening programs. Such programs are one of the best strategies for reducing cancer mortality.40 A national screening portfolio had not been defined until 2013, although screening was already being carried out in all autonomous communities for some types of cancer, such as breast cancer.41 As of 2013, breast and colorectal cancers have both been the target of population screening programs, and cervical cancer of an opportunistic program. Those autonomous communities that had not yet implemented screening programs were given a period of five years to initiate the programs, and 10 years to achieve full coverage (basically for colon cancer), although the current economic situation will not make it easy to achieve these goals.42 While population-based programs ensure more equitable access to the health system compared to opportunistic-based programs,41 some inequalities may persist, such as lower participation by ethnic minorities and underprivileged socioeconomic groups.40,41,43–51

In countries where healthcare cuts affect screening programs, cancer mortality is expected to increase in the coming years.52 Thus, it is essential that that the implementation and continuity of cancer screening programs in Spain are not affected by healthcare cuts.

Despite the negative consequences, periods of economic crisis can actually help promote primary cancer prevention by reducing unhealthy habits such as alcohol and tobacco consumption.5,21 One of the limitations of our study is that we did not evaluate health-related behaviours, socioeconomic variables or cancer stage at diagnosis time which are also often modified during times of economic crisis and can influence the appearance and severity of cancer. Because this information is not available in the Spanish Mortality Registry, it would be useful to investigate these variables in future studies to determine if they are linked to the gender differences observed in our study.

While cancer mortality has continued to decline since the onset of the crisis, its effects on cancer could be slow to appear. Consequently, another limitation of our study is that we analysed a post-crisis period of five years, which may be insufficient to detect major changes in mortality. In addition, given the latency periods of these cancers studied, their effects may appear in the next years. Thus, it would be useful to continue monitoring trends in cancer mortality in the coming years in conjunction with the evolution of the economic crisis.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates an overall downward trend in cancer mortality both before and after the onset of the economic crisis, but with a notable slowing down in the rate of decline since the crisis began. For lung cancer, there was a downward trend in men but an upward trend in women, while for colon cancer the trends are reversed and less pronounced. With respect to prostate and breast cancer, the onset of the crisis caused a slight slowing of their previous decline in men and women, respectively. These trends could change if the current austerity measures are maintained during the coming years, which would cause significant deterioration of the Spanish public healthcare system. Abolishing current austerity measures will be crucial in preventing a rise in cancer mortality in the future.

Increased unemployment along with lower investment in the public health sector are known to be associated with an increase in total cancer mortality, particularly of breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer. However, there are a limited research on economic crises and cancer mortality.

What does this study add to the literature?Since the onset of the economic crisis in Spain the rate of decline in cancer mortality has slowed significantly. This situation could be exacerbated by the current austerity measures in healthcare. Abolishing current austerity measures will be crucial in preventing a rise in cancer mortality in the future in Spain.

Carlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsAll authors made substantial contributions to conception and design of this study. L. Palència, M. Gotsens, M. Marí-Dell’Olmo and V. Puig-Barrachina performed data analysis. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data. J. Ferrando and L. Palència were involved in drafting the manuscript and the rest of the authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published

FundingThis research has been partially funded by the project entitled "Efectos de la crisis en la salud de la población y sus determinantes en España" (PI13/00897) funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (co-funded by European Regional Development Fund).

Conflicts of interestNone.