To document the prevalence of poor mental health by gender and social class, and to analyze if poor mental health is associated with the family roles or the employment status inside and outside the household.

MethodA cross-sectional study based on a representative sample of the Spanish population was carried out (n = 14,247). Mental health was evaluated using GHQ-12. Employment status, marital status, family roles (main breadwinner and the person who mainly carries out the household work) and educational level were considered as explanatory variables. Multiple logistic regression models stratified by gender and social class were fitted and adjusted odds ratios (aOR) were obtained.

ResultsGender and social class differences in the prevalence of poor mental health were observed. Unemployment was associated with higher prevalence. Among men the main breadwinner role was related to poor mental health mainly in those that belong to manual classes (aOR = 1.2). Among women, mainly among nonmanual classes, these problems were associated to marital status: widowed, separated or divorced (aOR = 1.9) and to dealing with the household work by themselves (aOR = 1.9).

ConclusionsIn Spain, gender and social class differences in mental health still exist. In addition, family roles and working situation, both inside and outside the household, could constitute a source of inequalities in mental health.

Conocer la prevalencia de mala salud mental por sexo y clase social, y analizar si la salud mental se relaciona con los roles familiares y la situación laboral fuera y dentro del hogar.

MétodoSe realizó un diseño transversal basado en una muestra representativa de la población española (n = 14.247). La salud mental se evaluó mediante el GHQ-12. Se consideraron como variables explicativas la situación laboral, el estado civil, el rol familiar (sustentador principal y persona que realiza el trabajo doméstico) y el nivel de estudios. Se ajustaron modelos de regresión logística estratificados por sexo y se obtuvieron las odds ratio ajustadas (ORa).

ResultadosSe observaron diferencias en la prevalencia de mala salud mental por sexo y clase social. El desempleo se asoció con mayor prevalencia. En hombres pertenecientes a clases menos favorecidas, el rol de sustentador principal se relacionó con mala salud mental (Ora = 1,2) En mujeres que pertenecían a clases más favorecidas, el estado civil viuda, separada o divorciada (ORa = 1,9) y realizar el trabajo doméstico solas (ORa = 1,9) se relacionaron con mala salud mental.

ConclusionesEn España, en salud mental continúa habiendo diferencias de sexo y clase social. Además, el rol familiar y la situación laboral fuera y dentro del ámbito doméstico podrían constituir también una fuente de desigualdad en salud mental.

Nowadays, one of the main factors that has led to a decline in quality of life, dependency and disability worldwide are mental health problems.1,2 In Spain, they are considered, together with neurologic diseases, as the number one cause of disability among non-infectious diseases.3

Prevalence of mental health problems has been assessed in several studies, both in the European population and in the Spanish population,4–10 finding in them variations according to the geographic area studied as well as across time.11,12 These facts show the relevance of a periodic and specific assessment of this prevalence for each geographic area, in order to try to decrease and prevent the consequences associated with it.

In relation to the factors associated with a higher prevalence of health problems, previous studies show a close relationship between gender social class and the prevalence of both physical and mental health problems.13–17 In addition, these studies find a higher prevalence of problems among women than among men, and among people who belong to the most deprived social classes in comparison with people belonging to the most favored social classes. These results show the necessity of bearing these factors in mind when carrying out population health studies, as is proposed through the intersectionality concept, which considers gender and social class as two of the main axes of physical and mental health inequality.18,19

Furthermore, different studies have been carried out in order to analyze possible gender differences in the influence on mental health of some socioeconomic variables such as the family role or the civil status.20,21 The results obtained point to the importance of the family roles and suggest that the paid-work related factors and the economic support for the family could be to a greater extent associated with men's mental health, while factors related to the domestic and family environment, could be more strongly associated with women's health.

With regard to the work situation and its relation to mental health, several studies have been carried out.22–24 Many of these studies have been centred on people having a certain work situation, such as employed and unemployed, and only some make reference to alternative situations like dedication to housework (i.e., serving as a homemaker) or other work situations. It is appropriate to take into account these situations in order to obtain a wider view of how work situation is related to mental health.

Therefore, in this context, the aims of the present study are: to analyze if mental health problems are associated with employment status as well as to family and household characteristics; and examine if there are differences in prevalence related to the gender and social class.

MethodsStudy design and participantsA cross-sectional study based on a representative sample of the non-institutionalized Spanish population (N = 21,007) was carried out. Data from the National Health Survey of Spain 2011/2012 (ENSE-2012) were used.25 The survey's questionnaires contain information on variables such as the occupational social class, the employment status, the family and household characteristics, as well as data on mental health through the inclusion of the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), a screening tool used to detect mental health problems. The sample of the ENSE-2012 was selected using a three-stage stratified sampling method, obtaining a response rate of 89%, from which, 28% represents reserve households to replace incidents in headlines.25 The information was collected through personal interviews between July 2011 and June 2012.

The selection criteria for the present study was as follows: people between 16 and 65 who answered the GHQ-12 and whose employment status was working, unemployed, dedicated to domestic work or other situation (n = 15,150). Due to possible effects of reverse causality those people unable to work (2.4%) were excluded. Furthermore, those people for whom it was not possible to determine their employment status (0.1%), social class (2.5%), marital or cohabitation status (0.1%) and the person who takes care of the housework (1.2%) were also excluded. The final sample included 14,247 people.

Variables- •

Mental health: assessed using the GHQ-12, a mental health screening tool for general population and non-psychiatric patients, validated for the Spanish population.26 The GHQ-12 evaluates the subjective mental state of the person and detects mainly two types of disorders: anxiety and depression. It consists of 12 Likert-type items with a 4 point response scale. A 2-point scoring method has been used, assigning 0 points to answers 0 and 1, and 1 point to answers 2 and 3, and then adding the points of the 12 items obtaining a total score between 0 and 12. A score of 3 or greater was considered to indicate poor mental health according to the proposal of the authors of the scale as well as in previous studies carried out in this population.8,22,26,27

- •

Occupational social class: based on the person's current or past work, and classified through the categories proposed by the working group on social determinants of the Spanish Society of Epidemiology.28 The social class categories have been grouped for the ENSE-2012 in: directors and managers of establishments with 10 or more employees and university degrees (class I), directors and managers of establishments with fewer than 10 employees and university diplomas (class II), intermediate occupations and self-employed people (class III), supervisors and workers in skilled technical occupations (class IV), skilled workers in the primary sector and other semi-skilled workers (class V) and unskilled workers (class VI). Due to the low number of people in some categories, the social classes were collapsed into two categories: nonmanual (classes I, II and III) and manual (classes IV, V and VI).

- •

Employment status. The following situations were considered: working, unemployed, dedicated to domestic work (i.e., serving as a homemaker) and other situations (included in this category are: people that are studying; retirees and early retirees and other situations not covered by the other categories)

- •

Family and household characteristics. Marital status (single, married or cohabiting and widowed or separated or divorced) and the family roles from two variables: main breadwinner (yes or no) and the person who mainly carries out the household work (yourself, yourself shared with someone else and someone else).

- •

Education. The following categories were considered: university studies, secondary or high school, primary or no education and other situations (including people whose educational degree does not have correspondence with the Spanish educational levels and people not covered by the other categories).

- •

Age: considered as a continuous variable.

A descriptive analysis of prevalence of poor mental health according to the employment status and the family and household characteristics stratified by gender and social class was performed. Differences by gender in the studied variables were tested using Chi Square test for categorical variables and t test for age and GHQ-12 when was considered as a continuous variable. Secondly, multivariate logistic regression models were fitted to analyze the relationship between mental health and employment status, socioeconomic variables as well as family and household variables. Also, a multivariate sub-analysis taking into account only the people who was working and with marital status married or cohabiting was performed. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and respective confidence intervals of 95% (CI95%) were obtained. All models were stratified by gender and social class individually and jointly, and were adjusted by all the explanatory variables and age as a continuous variable. The models including only working population with marital status married or cohabiting were stratified by gender and social class jointly.

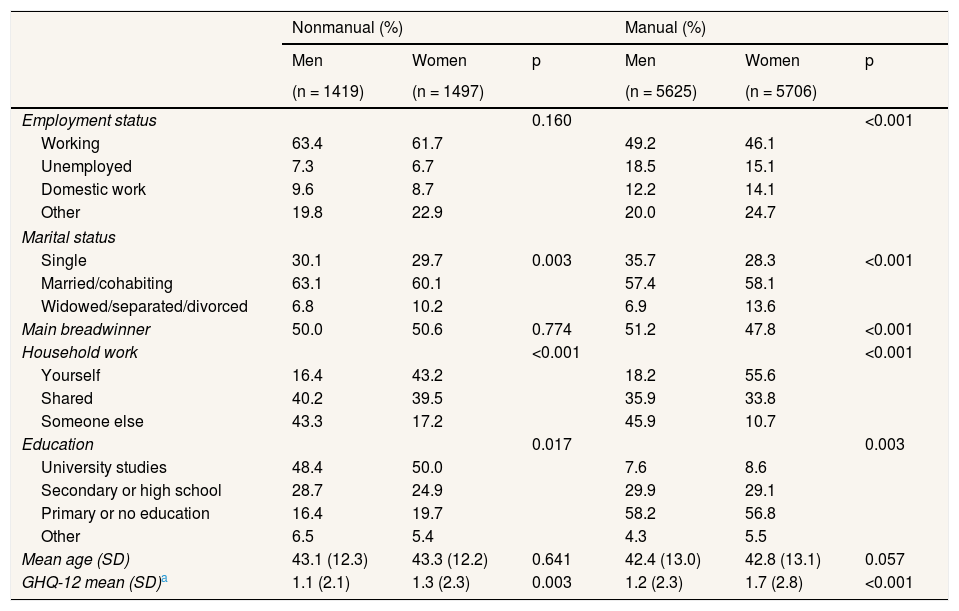

ResultsTable 1 shows the characteristics of the study sample by gender and social class. Of the participants, more than half were women (50.6%) and most were from the manual social classes (men: 79.9%; women: 79.2%). Regarding the employment status, for both genders the most frequent situation was working, though this figure was slightly lower in the manual social classes. Among both genders unemployment was higher among the manual social classes than in nonmanual. The most common marital status was married or cohabiting and about half of the people assume the role of main breadwinner. In terms of household chore allocation, there are differences between men and women. While among men the most frequent situation, independent of the social class, was that these chores were done by another person, among women the most frequent situation was that they carry out these chores by themselves.

General description of the sample by gender and social class.

| Nonmanual (%) | Manual (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | |

| (n = 1419) | (n = 1497) | (n = 5625) | (n = 5706) | |||

| Employment status | 0.160 | <0.001 | ||||

| Working | 63.4 | 61.7 | 49.2 | 46.1 | ||

| Unemployed | 7.3 | 6.7 | 18.5 | 15.1 | ||

| Domestic work | 9.6 | 8.7 | 12.2 | 14.1 | ||

| Other | 19.8 | 22.9 | 20.0 | 24.7 | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 30.1 | 29.7 | 0.003 | 35.7 | 28.3 | <0.001 |

| Married/cohabiting | 63.1 | 60.1 | 57.4 | 58.1 | ||

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 6.8 | 10.2 | 6.9 | 13.6 | ||

| Main breadwinner | 50.0 | 50.6 | 0.774 | 51.2 | 47.8 | <0.001 |

| Household work | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Yourself | 16.4 | 43.2 | 18.2 | 55.6 | ||

| Shared | 40.2 | 39.5 | 35.9 | 33.8 | ||

| Someone else | 43.3 | 17.2 | 45.9 | 10.7 | ||

| Education | 0.017 | 0.003 | ||||

| University studies | 48.4 | 50.0 | 7.6 | 8.6 | ||

| Secondary or high school | 28.7 | 24.9 | 29.9 | 29.1 | ||

| Primary or no education | 16.4 | 19.7 | 58.2 | 56.8 | ||

| Other | 6.5 | 5.4 | 4.3 | 5.5 | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 43.1 (12.3) | 43.3 (12.2) | 0.641 | 42.4 (13.0) | 42.8 (13.1) | 0.057 |

| GHQ-12 mean (SD)a | 1.1 (2.1) | 1.3 (2.3) | 0.003 | 1.2 (2.3) | 1.7 (2.8) | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation.

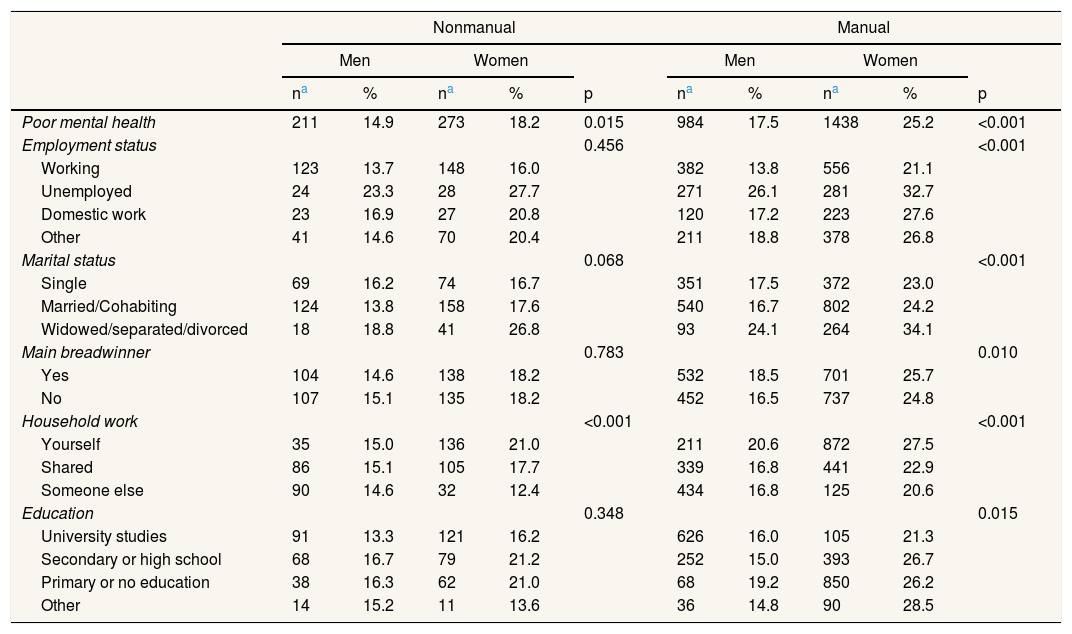

Table 2 shows the prevalence of poor mental health across independent variables. A higher prevalence among women, and among those that belong to manual social classes (men: 17.5%; women: 25.2%) than nonmanual (men: 14.9%; women: 18.2%) was observed. In relation to the employment status, there was a higher prevalence among unemployed people in both genders, independent of the social class. Additionally, among women of manual social classes higher rates were observed across all working situations. Regarding family and household characteristics, there was a higher observed prevalence, independent of the gender and the social class, among the widowed, separated or divorced. A higher prevalence was also found among those that assume the main breadwinner role and belong to manual social classes. As for household work allocation, higher rates of poor mental health were found among people that carry out with this work by themselves, except among men from nonmanual social classes for whom the highest prevalence was observed among those that share these tasks (15.1%).

Poor mental health prevalence (%) across independent variables stratified by gender and social class.

| Nonmanual | Manual | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||||||

| na | % | na | % | p | na | % | na | % | p | |

| Poor mental health | 211 | 14.9 | 273 | 18.2 | 0.015 | 984 | 17.5 | 1438 | 25.2 | <0.001 |

| Employment status | 0.456 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Working | 123 | 13.7 | 148 | 16.0 | 382 | 13.8 | 556 | 21.1 | ||

| Unemployed | 24 | 23.3 | 28 | 27.7 | 271 | 26.1 | 281 | 32.7 | ||

| Domestic work | 23 | 16.9 | 27 | 20.8 | 120 | 17.2 | 223 | 27.6 | ||

| Other | 41 | 14.6 | 70 | 20.4 | 211 | 18.8 | 378 | 26.8 | ||

| Marital status | 0.068 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Single | 69 | 16.2 | 74 | 16.7 | 351 | 17.5 | 372 | 23.0 | ||

| Married/Cohabiting | 124 | 13.8 | 158 | 17.6 | 540 | 16.7 | 802 | 24.2 | ||

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 18 | 18.8 | 41 | 26.8 | 93 | 24.1 | 264 | 34.1 | ||

| Main breadwinner | 0.783 | 0.010 | ||||||||

| Yes | 104 | 14.6 | 138 | 18.2 | 532 | 18.5 | 701 | 25.7 | ||

| No | 107 | 15.1 | 135 | 18.2 | 452 | 16.5 | 737 | 24.8 | ||

| Household work | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||||||

| Yourself | 35 | 15.0 | 136 | 21.0 | 211 | 20.6 | 872 | 27.5 | ||

| Shared | 86 | 15.1 | 105 | 17.7 | 339 | 16.8 | 441 | 22.9 | ||

| Someone else | 90 | 14.6 | 32 | 12.4 | 434 | 16.8 | 125 | 20.6 | ||

| Education | 0.348 | 0.015 | ||||||||

| University studies | 91 | 13.3 | 121 | 16.2 | 626 | 16.0 | 105 | 21.3 | ||

| Secondary or high school | 68 | 16.7 | 79 | 21.2 | 252 | 15.0 | 393 | 26.7 | ||

| Primary or no education | 38 | 16.3 | 62 | 21.0 | 68 | 19.2 | 850 | 26.2 | ||

| Other | 14 | 15.2 | 11 | 13.6 | 36 | 14.8 | 90 | 28.5 | ||

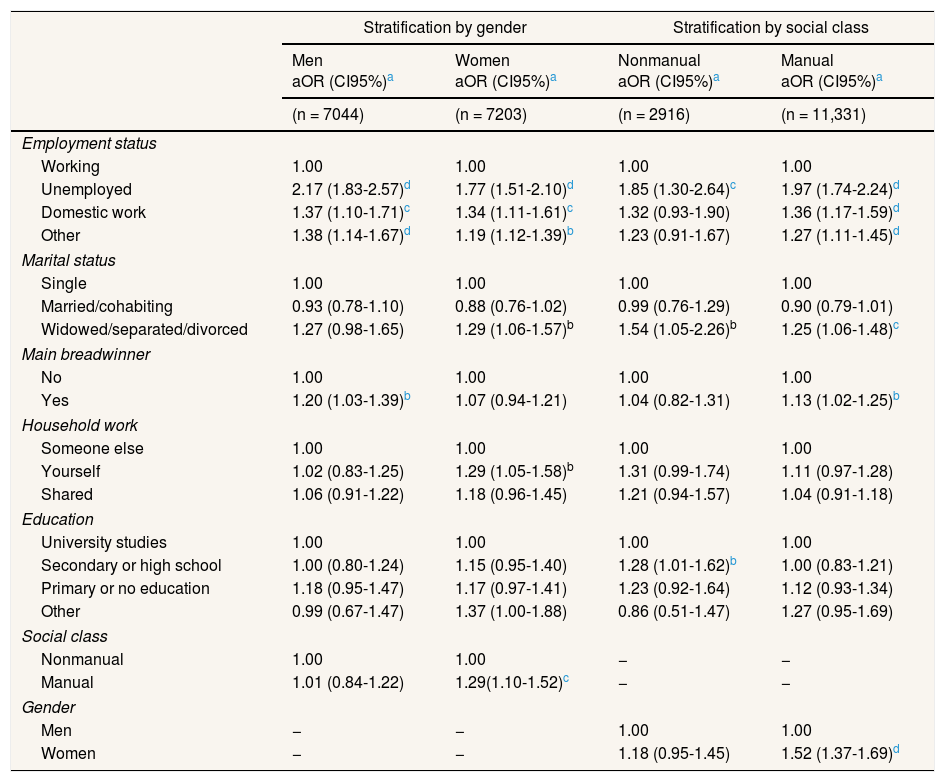

Table 3 shows the association between employment status, domestic and family characteristics and poor mental health stratified by gender in the first two columns and by social class in the last two columns. Unemployment, the dedication to domestic work and other working situations were related to poor mental health in both genders in the manual social classes. In nonmanual social classes, poor mental health was only related to unemployment (aOR = 1.85; 95%CI: 1.30-2.64). Furthermore, the civil status of widowed, separated or divorced was associated with poor mental health in both social classes and in women. Regarding family roles, only among men (aOR = 1.20; 95%CI: 1.03-1.39) and among the manual social classes (aOR = 1.13; 95%CI: 1.02-1.25) was a relationship between poor mental health and main breadwinner role observed, while only among women a relationship between carrying out the household work by themselves and poor mental health (aOR = 1.29; 95%CI: 1.05-1.58) was found. As for gender and social class, an association between poor mental health and belonging to the manual social classes was only found in women.

Association between poor mental health, employment status and family and household characteristics..

| Stratification by gender | Stratification by social class | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men aOR (CI95%)a | Women aOR (CI95%)a | Nonmanual aOR (CI95%)a | Manual aOR (CI95%)a | |

| (n = 7044) | (n = 7203) | (n = 2916) | (n = 11,331) | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Working | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 2.17 (1.83-2.57)d | 1.77 (1.51-2.10)d | 1.85 (1.30-2.64)c | 1.97 (1.74-2.24)d |

| Domestic work | 1.37 (1.10-1.71)c | 1.34 (1.11-1.61)c | 1.32 (0.93-1.90) | 1.36 (1.17-1.59)d |

| Other | 1.38 (1.14-1.67)d | 1.19 (1.12-1.39)b | 1.23 (0.91-1.67) | 1.27 (1.11-1.45)d |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married/cohabiting | 0.93 (0.78-1.10) | 0.88 (0.76-1.02) | 0.99 (0.76-1.29) | 0.90 (0.79-1.01) |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 1.27 (0.98-1.65) | 1.29 (1.06-1.57)b | 1.54 (1.05-2.26)b | 1.25 (1.06-1.48)c |

| Main breadwinner | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.20 (1.03-1.39)b | 1.07 (0.94-1.21) | 1.04 (0.82-1.31) | 1.13 (1.02-1.25)b |

| Household work | ||||

| Someone else | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yourself | 1.02 (0.83-1.25) | 1.29 (1.05-1.58)b | 1.31 (0.99-1.74) | 1.11 (0.97-1.28) |

| Shared | 1.06 (0.91-1.22) | 1.18 (0.96-1.45) | 1.21 (0.94-1.57) | 1.04 (0.91-1.18) |

| Education | ||||

| University studies | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Secondary or high school | 1.00 (0.80-1.24) | 1.15 (0.95-1.40) | 1.28 (1.01-1.62)b | 1.00 (0.83-1.21) |

| Primary or no education | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 1.17 (0.97-1.41) | 1.23 (0.92-1.64) | 1.12 (0.93-1.34) |

| Other | 0.99 (0.67-1.47) | 1.37 (1.00-1.88) | 0.86 (0.51-1.47) | 1.27 (0.95-1.69) |

| Social class | ||||

| Nonmanual | 1.00 | 1.00 | − | − |

| Manual | 1.01 (0.84-1.22) | 1.29(1.10-1.52)c | − | − |

| Gender | ||||

| Men | − | − | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Women | − | − | 1.18 (0.95-1.45) | 1.52 (1.37-1.69)d |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI95%: confidence interval of 95%.

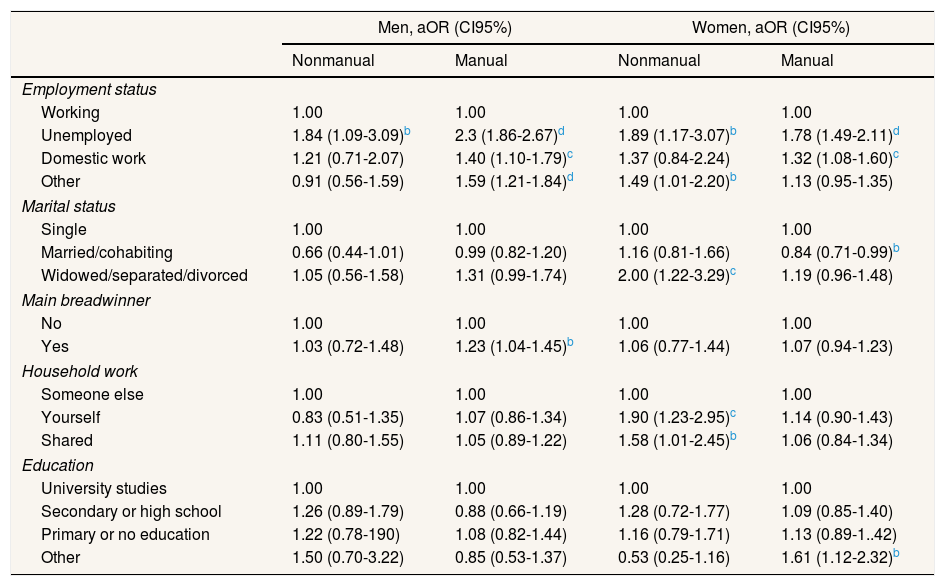

Table 4 shows the association between poor mental health, employment status and domestic and family characteristics stratified jointly by gender and social class. Concerning employment status, unemployment was related to poor mental health independently of the gender and the social class. Also, a relationship was found between the dedication to domestic work, other working situations and poor mental health in both genders in manual social classes. Regarding family and domestic characteristics, an association between poor mental health and being widowed, separated or divorced (aOR = 2.00; 95%CI: 1.22-3.29), doing the household work by themselves (aOR = 1.90; 95%CI: 1.23-2.95) and shared (aOR = 1.58; 95%CI: 1.01-2.45) was only found among women from nonmanual social classes, not being found any statistically significant relationship in the sub-analysis carried out in working population with marital status married or cohabiting (see Table I, online Appendix). Meanwhile, only among men that belong to manual social classes an association between being the main breadwinner and poor mental health was observed (aOR = 1.23; 95%CI: 1.04-1.45).

Association between poor mental health, employment status and family and household characteristics stratified by gender and social class.

| Men, aOR (CI95%) | Women, aOR (CI95%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonmanual | Manual | Nonmanual | Manual | |

| Employment status | ||||

| Working | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Unemployed | 1.84 (1.09-3.09)b | 2.3 (1.86-2.67)d | 1.89 (1.17-3.07)b | 1.78 (1.49-2.11)d |

| Domestic work | 1.21 (0.71-2.07) | 1.40 (1.10-1.79)c | 1.37 (0.84-2.24) | 1.32 (1.08-1.60)c |

| Other | 0.91 (0.56-1.59) | 1.59 (1.21-1.84)d | 1.49 (1.01-2.20)b | 1.13 (0.95-1.35) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Married/cohabiting | 0.66 (0.44-1.01) | 0.99 (0.82-1.20) | 1.16 (0.81-1.66) | 0.84 (0.71-0.99)b |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 1.05 (0.56-1.58) | 1.31 (0.99-1.74) | 2.00 (1.22-3.29)c | 1.19 (0.96-1.48) |

| Main breadwinner | ||||

| No | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 1.03 (0.72-1.48) | 1.23 (1.04-1.45)b | 1.06 (0.77-1.44) | 1.07 (0.94-1.23) |

| Household work | ||||

| Someone else | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Yourself | 0.83 (0.51-1.35) | 1.07 (0.86-1.34) | 1.90 (1.23-2.95)c | 1.14 (0.90-1.43) |

| Shared | 1.11 (0.80-1.55) | 1.05 (0.89-1.22) | 1.58 (1.01-2.45)b | 1.06 (0.84-1.34) |

| Education | ||||

| University studies | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Secondary or high school | 1.26 (0.89-1.79) | 0.88 (0.66-1.19) | 1.28 (0.72-1.77) | 1.09 (0.85-1.40) |

| Primary or no education | 1.22 (0.78-190) | 1.08 (0.82-1.44) | 1.16 (0.79-1.71) | 1.13 (0.89-1..42) |

| Other | 1.50 (0.70-3.22) | 0.85 (0.53-1.37) | 0.53 (0.25-1.16) | 1.61 (1.12-2.32)b |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI95%: confidence interval of 95%.

a Odds ratios adjusted by all explanatory variables and age.

This study, based on a representative sample of the Spanish population, shows new evidence of the existence of both gender and social class differences in mental health, and also provides evidence that these differences are related to family and household characteristics. As far as we know, this is one of the few population based studies about mental health carried out in the south of Europe that considers the work situation inside and outside the home setting. It also improves on some of the limitations in previous studies by taking into account both the influence of the social class and the gender perspective on health, and considering the allocation of household work.

Gender and social class differences in mental healthIn line with the results obtained in previous studies and in the context of the current economic crisis that started in 2009,8,13,29 the prevalence of poor mental health was higher among women regardless of the social class they belong to, showing that gender differences in mental health still exist in Spain. Also, in previous studies carried out with ENSE-2006 data, lower prevalence among men and slightly higher prevalence among women were observed,8,9 providing the results of the present study new evidence in favour of the proposal by Bartoll et al.10 regarding a possible pattern of rising prevalence of poor mental health among men and slight decrease among women in a context of economic crisis. This pattern could be related, as it was proposed by this study, to different factors being some of them the employment status, the social class and the educational level.

Regarding social class, the prevalence of poor mental health was higher among people belonging to the manual social classes in both genders. These results are consistent with previous findings that in both the general population and the working population, belonging to a manual social class and experiencing economic hardship were potential determinants of poor mental health.15,16,30,31 Also, the present results reinforce the hypotheses that taking political measures in order to reduce social inequalities could have a positive impact on mental health, as was suggested in previous studies.32,33

As for the factors associated to poor mental health, differences both in function of gender as in function of social class were found. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that in a country like Spain with traditional family policies, the variables related to the paid work and the economic support of the family unit are mainly related to men's mental health, and the socioeconomic variables and those related to the domestic work with the women's mental health.17,22,33–35

Mental health, employment status and household and family characteristicsAmong the different considered work situations, and in line with the results of previous studies,24,36 there was a higher prevalence of poor mental health among unemployed people regardless of gender and social class, and lower prevalence among the employed. These results could be explained through the higher financial stress and uncertainty about the future that the unemployed suffer with respect to the employed.34

Regarding the employment status, the results suggest that its effect on mental health could be influenced by social class, since unemployment was related to poor mental health regardless of social class, while the dedication to household work and other working situations have only been associated with mental health problems among people belonging to the manual social classes. The results of the present study suggest a new hypothesis pointing up to the mediating effect that the social class could have in the impact of different work situations on mental health. In this way, belonging to a nonmanual or a manual social class, could determine the impact that the different work situations have on mental health, as has been hypothesized in some studies.36 Further studies are necessary in order to clarify the relation between social class, work situation and mental health.

Moreover, taking into account the household and family characteristics, it was observed that, when considering men and women in the complete sample, men were more likely to report being the main breadwinner while women were more likely to report being primarily responsible for household chores. These results, in line with previous studies,20,22,32,33 show that there still exists a gender separation in work and family roles in Spain that assigns the role of economically supporting of the family unit to men, and the role of worker in household and family environment to women. Regarding family roles, several studies have shown a relationship between them and mental health problems.20,30,37 Also, and in spite of not having found any statistically significant relationship, the results found in our study in the sub-sample of working population with married or cohabiting marital status (see Table I, online Appendix) were congruent with the results found in these studies as well as in the whole study population. These results suggest that the main breadwinner role could be associated with mental health problems through the stress and the worry about earning enough to cover household expenses that this role can have in some people. This stress may be higher among the people that belong to manual social classes in a crisis situation like the current one in Spain. Additionally, the role of household and family workers assigned to women in a country with traditional family policy such as Spain, could be related to poor mental health, as a result of the overload that these chores could pose when they are added to paid work,21,22,34 being adequate in future studies to take into account the interaction between the employment status and the family roles in order to determine this relationship.

LimitationsRegarding the limitations of the current study, a cross-sectional design has been used. This design does not allow for establishing the direction of the causal relation of the obtained results. However, and following the results obtained in previous studies with relatively similar goals,20,21,30 our results could serve as starting point for future studies suggesting the hypothesis that the work situation and the family and household variables could have an influence on mental health, and not the contrary. Moreover, among the ENSE-2012 participants, the institutionalized population is not included.25 It would be appropriate to consider this type of population in order to get a more adjusted representation of poor mental health in the Spanish population, especially considering that poor mental health is a possible factor associated with institutionalization.

Finally, it should be mentioned the limitation related to the inclusion in the models of the interactions between gender and social class on one hand, and between family roles and employment status on the other. Despite the stratification made in our study, the inclusion of these interactions in future research, and also have in mind the possible colinearity between adjustment variables, could allow to have a wider view of the relationship between these factors and mental health.

ConclusionsThe results of the current study show that in Spain there are still gender and social class differences in mental health, and that these differences could be related to the family role separation and sexual division of work.

Regarding the variables associated with poor mental health, the work situation could be a factor which is associated with mental health to a greater extent among people belonging to the manual social classes.

Men who report being the main breadwinner are more likely to have poor mental health than men who do not report that role, mainly in the manual social classes. Women who report primary responsibility for household chores are more likely to have poor mental health than women who do not report that role mainly in the nonmanual social classes.

All the results suggest that in addition to gender and social class, family roles and the work done outside and inside the household and family environment could constitute a source of inequalities in mental health.

Editor in chargeMaría del Mar García-Calvente.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Several studies have demonstrated that gender and social class are factors close related to mental health. Other factors possibly related to mental health as the family roles and the employment status inside the household have been less studied.

What does this study add to the literature?Gender and social inequalities in mental health in Spain still exist. Family roles influences mental health differently according to sex and social class, being the work done outside and inside household a source of inequalities in mental health.

All authors conceived the design of the study. V. Martin, L. Artazcoz and A.J. Molina supervised all aspects of job performance. J. Arias-de la Torre conducted the statistical analysis. J. Arias-de la Torre, A.J. Molina and T Fernández-Villa wrote the manuscript. All authors have critically reviewed and agreed this final version of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.