To analyze by gender the relationship of forced displacements due to neglected housing insecurity with the physical and mental health of renters in Barcelona in 2019, distinguishing between economic (EHI) and legal (LHI) housing insecurity.

MethodWe conducted a cross-sectional study based on the Survey of the Living Conditions of Renters in the Barcelona Metropolitan Area 2019 (1021 women; 584 men). Self-reported health and mental well-being were the dependents variables; the main explanatory variable was neglected housing insecurity. We used adjusted robust Poisson regression models to compare health outcomes among people affected by neglected housing insecurity and those who were not affected.

ResultsWe observed that the probability of worse health outcomes are greater in those affected by EHI, followed by those affected by LHI, both compared to those who have not been affected by housing insecurity. This association are mainly observed in mental health of renters affected by EHI, even after adjusting for socioeconomic and other housing variables (in women PR: 1,17, CI95%: 1,03-1,33; in men PR: 1,21, CI95%: 1,01-1,43).

ConclusionsNeglected housing insecurity is associated with worse mental health. Enhancing the visibility of neglected housing insecurity and raising awareness of its effects on health is urgently needed to tackle this massive but hidden problem.

Analizar la relación de la inseguridad residencial desatendida sobre la salud física y mental de personas inquilinas residentes en Barcelona en 2019, distinguiendo entre inseguridad residencial económica (IRE) y legal (IRL).

MétodoEstudio transversal basado en la Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida de Personas Inquilinas en el Área Metropolitana de Barcelona 2019 (1021 mujeres y 584 hombres). Las variables dependientes fueron salud autopercibida y bienestar mental, y la principal variable explicativa fue inseguridad residencial desatendida. Se utilizaron modelos ajustados de Poisson robusta para comparar los resultados de salud entre personas afectadas y no afectadas.

ResultadosLa probabilidad de peor salud fue mayor en las personas afectadas por IRE, seguidas por las afectadas por IRL, ambas comparadas con quienes no habían sido afectadas. Esta asociación fue principalmente observada en la salud mental de las personas inquilinas afectadas por IRE, incluso tras ajustar por variables sociodemográficas y otras de vivienda (en mujeres, PR: 1,17, IC95%: 1,03-1,33; en hombres, PR: 1,21, IC95%: 1,01-1,43).

ConclusionesLa inseguridad residencial desatendida se asocia con peor salud mental. Se necesita urgentemente visibilizar la inseguridad residencial desatendida y tomar conciencia de sus efectos en la salud para así afrontar este masivo, pero oculto, problema.

Currently, there is a widespread housing crisis, affecting millions of lives worldwide, and Europe is no exception.1 This problem has become more evident after the housing market bubble burst in 2007, forcing various European states to take measures to alleviate the consequences of the collapse of the mortgage market.2 These actions led to a shift in the housing bubble from property tenure to renting, as exemplified in Spain,3,4 Greece and Croatia.5,6 In the countries of the European Union, the rate of households allocating more than 40% of their income to rent has increased (rates from 26.2% to 28%, in 2012 and 2016, respectively), while this rate has decreased in households with mortgages (from 8.3% to 5.4%).5,6

Housing insecurity is a complex phenomenon that may affect people's lives related to the housing dimensions of accessibility/affordability and stability.7 These dimensions, in turn, are mainly linked to economic and legal issues,8,9 such as living without the security of legal tenure (sub-renting, squatting or doubling-up), or being under a legal eviction process.9

However, there are other cases of housing insecurity that are less visible, usually naturalized due to their ordinary nature and lack of formal records.10,11 This is the case of situations qualitatively different from the formal eviction process and which, therefore, do not involve a judicial or police process.10,11 These situations are neglected types of housing insecurity, which we have classified into economic housing insecurity (being forced to leave a dwelling due to abusive rent increases or loss of household income) and legal housing insecurity (being forced to leave a dwelling in the absence of a legal lease agreement or unilateral termination of a valid lease agreement).

In Spain, the movement of the housing market bubble toward rental tenure can be observed in several indicators. For example, in the 2013-2019 period, housing prices decreased, while rents increased by 50%. This trend occurred in all the provincial capitals of the country, such as Barcelona.12,13 This trend is inconsistent with the household income growth in the country, which increased by only 1.3% in the same period.14 Thus, in 2016, 43% of renters allocated 40% or more of their oncome to housing costs.6

Similarly, in this period, 440,107 evictions were registered in the country, 58% of them due non-payment of rent.15 The autonomous community with the most evictions during this period was Catalonia, with 100,935 evictions (23% of the national total), of which 64.8% were due to rental reasons.15 This situation is clearer in Barcelona city, where 84% of evictions are due to rent arrears.14 Even though homeowners are affected by housing-related problems, the housing crisis has increased among renters, reflecting the shift in the housing bubble from the property market to the rental market.6,14,15

Faced with this emergency housing context, various social movements emerged to tackle and safeguard people's right to housing.16 Thus, in 2017 the “Sindicat de Llogateres” (Renters’ Union) was formed in Barcelona, whose main objective is to foster the collective vindication of renters’ rights and to influence administrative and government-related policies.11

As far as we know, most of the studies on the topic have either addressed the problem of housing insecurity among owners or have not distinguished among types of tenure. Moreover, few studies have specifically addressed the relationship between housing insecurity and poor in renters.17–21 For example, regarding general health, a study of 27 countries of European Union concluded that persons with housing insecurity reported worse self-rated health than unaffected individuals. Moreover, the negative health effects on renters were greater than those experienced by people with other types of tenure, even after adjustment by other sociodemographic variables.18 The mental health effects of housing insecurity have been reported to be depression, anxiety and stress,17,19–21 mostly affecting women,20 single-parent households19 and those with lower incomes.17,18,21 It has also been observed that these effects are maintained over years, related to insecurities in other areas of people's lives (food, work, family life, and others), and have greater negative effects on the mental health of renters than that of owners.17,19,20

Despite the severity of this housing emergency, so far there is insufficient evidence on the relationship between health and neglected housing insecurity in renters, hindering policy design to tackle this issue. This study aimed to analyze the association of housing insecurity, both in its legal and economic dimensions, with self-rated health and mental health by gender among renters in Barcelona city in 2019.

MethodWe performed a cross-sectional study. The study population consisted of people over 18 years old who were renters living in Barcelona city and who voluntarily completed the self-administered web survey “Renters’ Living Conditions of the Barcelona Metropolitan Area 2019”. The survey was designed by the Sindicat de Llogateres, La Hidra Cooperativa and the Barcelona Public Health Agency and was disseminated by social networks. The secondary data were provided by the Sindicat de Llogateres and La Hidra Cooperativa. The survey collected sociodemographic, residential and health information from the rental upswing period between the years 2014-2019.22 Data were collected between March and May 2019 and, to ensure the independence of the observations, only one person was selected from each household. The survey was completed by 2051 individuals; subsequently, we excluded those not residing in Barcelona city. In addition, people who reported having been affected by formal evictions (n=8) were excluded as they were not part of the phenomenon to be studied. Thus, the study sample included 1637 participants (1021 women, 584 men, and 32 people not identifying with binary gender).

We used two measures of health status: mental health and self-rated health. Mental health was evaluated using the short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS), which has been found to be a good proxy for mental health.23 The variable was categorized in two groups: mental well-being (>26 points) and mental discomfort (≤26 points).23,24 Self-rated health was evaluated using the 5-category question “How would you say your health is in general?” We created a dichotomous outcome variable: good health (excellent, very good, good) and poor health (fair, poor).25

The main explanatory variable, neglected housing insecurity, was constructed from two questions: “Have you changed your address in the last 5 years?” and “What was the main reason for this move?” We used this variable as categorical, including any of the following responses in the category “Legal Housing Insecurity” (LHI): “because the owner decided to end or not to renew the rental contract”, or “because the owner decided to evict me in the absence of a rental contract”. In contrast, the category “Economic Housing Insecurity” (EHI) was composed of persons who responded “due to financial difficulties because of the increase in housing prices” or “due to financial difficulties because of a decrease in household income”. Finally, the category “Without Housing Insecurity” was composed of both persons who did not move home and those who responded “it was a voluntary move, it was better adapted to my needs” or “it was a voluntary move, the dwelling was in poor physical condition”.

The following adjustment variables were included: employment status, occupational social class,26 age, nationality, rental situation, and risk of involuntary mobility in the next 6 months. Gender was treated as a stratification variable, based on the question “with which gender do you identify yourself?” (women, men, non-binary).

We carried out a descriptive analysis of the study variables to determine their distribution. Then, to carry out the next steps of the analysis, all persons not identifying with binary gender were excluded because there were very few cases (n=32), leaving a sample of 1605 individuals. Subsequently, a bivariate analysis was performed between the explanatory variable of the study and the sociodemographic and dependent variables, obtaining the prevalence between affected and unaffected people, and their magnitude of association using the chi-square or Fisher exact tests. Then, age-adjusted robust Poisson regression models (PRa) were fitted to compare health outcomes among people affected by neglected housing insecurity and those who were not affected. Finally, we calculated an adjusted model that included housing variables and the most relevant sociodemographic variables according to Wald's test (PRb). All the analyses were carried out stratifying by gender, using the statistical software STATA15.

ResultsAnalysis of the sociodemographic characteristics of the study sample showed that 50% of women were aged 35-50 years, while men and people with non-binary gender were mostly aged 18-34 years (45% and 46.9%) and 35-50 years (44.9% and 43.8%, respectively). Most participants were from Spain (∼90%). Regarding socioeconomic status, most reported being employed (women, 84.4%; men, 86.8%; non-binary gender, 84.8%) and belonging to managerial and senior professionals’ social classes (women, 63.9%; men, 58.6%; non-binary gender, 56.3%) (Table 1).

Participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

| Independent sociodemographic variables | Women (n=1021) | Men (n=584) | Non-binary gender (n=32) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Age (years) | |||||||

| 18-34 | 397 | 38.9 | 263 | 45.0 | 15 | 46.9 | 0.22 |

| 35-50 | 512 | 50.2 | 262 | 44.9 | 14 | 43.8 | |

| 51-60 | 67 | 6.6 | 37 | 6.3 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| 61-87 | 37 | 3.6 | 14 | 2.4 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Missing | 8 | 0.8 | 8 | 1.4 | 1 | 3.1 | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Nationality | |||||||

| Spain | 915 | 89.6 | 546 | 93.5 | 29 | 90.6 | 0.07 |

| European Union | 65 | 6.4 | 23 | 3.9 | 3 | 9.4 | |

| Non-European Union | 40 | 3.9 | 15 | 2.6 | -- | -- | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.1 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employed | 867 | 84.9 | 507 | 86.8 | 27 | 84.4 | 0.57 |

| Unemployed | 87 | 8.5 | 37 | 6.3 | 3 | 9.4 | |

| Other | 65 | 6.4 | 39 | 6.7 | 2 | 6.3 | |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Occupational social class | |||||||

| I-II | 656 | 64.3 | 342 | 58.6 | 18 | 56.3 | 0.28 |

| III-IV | 206 | 20.2 | 124 | 21.2 | 8 | 25.0 | |

| V-VI-VII | 103 | 10.1 | 75 | 12.8 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Missing | 56 | 5.5 | 43 | 7.4 | 2 | 6.3 | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

For housing conditions, most renters reported that they individually paid all the rent and housing costs (40.6%, women; 41.6%, men; 37.5%, non-binary gender), followed by those who rented with more people sharing the housing costs (38.3%, women; 38%, men; 28.1%, non-binary gender). In addition, most participants reported they were not at risk of involuntary displacement in the next 6 months.

Analysis of neglected housing insecurity showed that, among women, 12.4% reported they were under LHI and 12.3% were under EHI. Among men, 14.9% reported they were under LHI and 9.3% under EHI. Among persons not identifying with binary gender, the percentages were 12.5% and 25%, respectively (Table 2).

Participants’ housing and health characteristics.

| Women (n=1021) | Men (n=584) | Non-binary gender (n=32) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p | |

| Independent sociodemographic variables | |||||||

| Rental situation | |||||||

| Rent whole house | 414 | 40.6 | 243 | 41.6 | 12 | 37.5 | 0.35 |

| Shared economy | 391 | 38.3 | 222 | 38.0 | 9 | 28.1 | |

| No shared economy | 170 | 16.7 | 93 | 15.9 | 7 | 21.9 | |

| Rent room | 42 | 4.1 | 25 | 4.3 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Missing | 4 | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Risk of involuntary mobility | |||||||

| No | 547 | 53.6 | 340 | 58.2 | 19 | 59.4 | 0.22 |

| Yes | 134 | 13.1 | 79 | 13.5 | 2 | 6.3 | |

| Don’t know | 339 | 33.2 | 165 | 28.3 | 11 | 34.4 | |

| Missing | 1 | 0.10 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Independent principal variable | |||||||

| Neglected housing insecurity | |||||||

| No | 771 | 75.5 | 443 | 75.9 | 20 | 62.5 | 0.05 |

| Yes, legal problems | 128 | 12.5 | 87 | 14.9 | 4 | 12.5 | |

| Yes, economic problems | 119 | 11.7 | 54 | 9.3 | 8 | 25.0 | |

| Missing | 3 | 0.29 | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Dependents variables | |||||||

| Mental well-being | |||||||

| Mental well-being | 381 | 37.3 | 222 | 38.0 | 7 | 21.9 | 0.17 |

| Mental discomfort | 636 | 62.3 | 357 | 61.1 | 25 | 78.1 | |

| Missing | 4 | 0.4 | 5 | 0.9 | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

| Self-rated health | |||||||

| Good | 901 | 88.3 | 525 | 89.9 | 27 | 84.4 | 0.44 |

| Bad | 120 | 11.8 | 56 | 10.1 | 5 | 15.6 | |

| Missing | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

| Total | 1021 | 100 | 584 | 100 | 32 | 100 | |

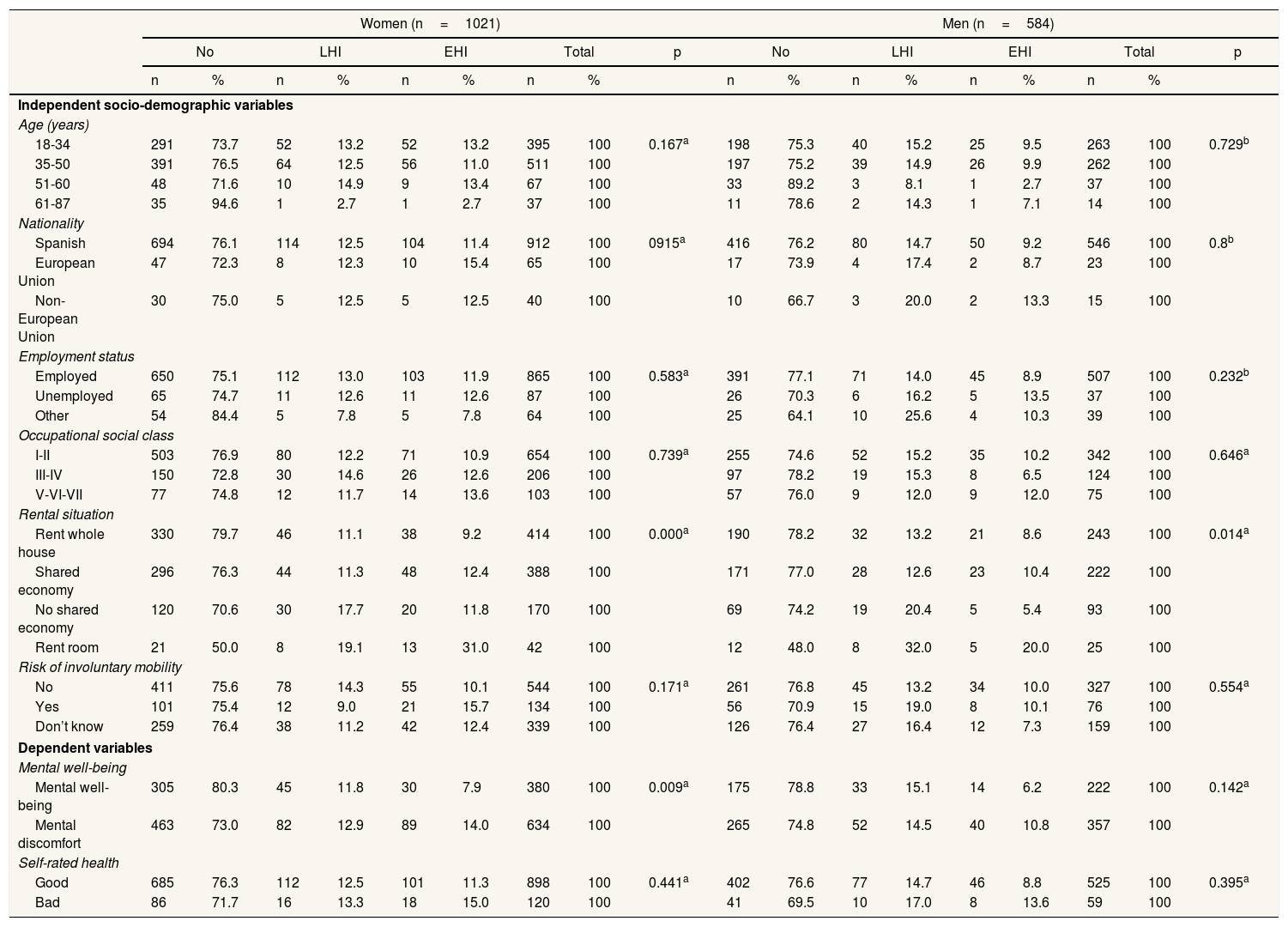

The group most affected by neglected housing insecurity, both legal and economic, were those renting a room (women, 19.1% and 31%, and men, 32% and 20%, respectively). The profile of people affected by LHI was mainly men from non-European Union countries (20%) and people who rented with other people without shared economy (women, 17.7%; men, 20.4%). EHI mainly affected people from the manual class (women, 13.6%; men, 12%) (Table 3).

Percentages of explanatory variables and health outcomes in women and men affected by neglected housing insecurity.

| Women (n=1021) | Men (n=584) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | LHI | EHI | Total | p | No | LHI | EHI | Total | p | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Independent socio-demographic variables | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||||||||||

| 18-34 | 291 | 73.7 | 52 | 13.2 | 52 | 13.2 | 395 | 100 | 0.167a | 198 | 75.3 | 40 | 15.2 | 25 | 9.5 | 263 | 100 | 0.729b |

| 35-50 | 391 | 76.5 | 64 | 12.5 | 56 | 11.0 | 511 | 100 | 197 | 75.2 | 39 | 14.9 | 26 | 9.9 | 262 | 100 | ||

| 51-60 | 48 | 71.6 | 10 | 14.9 | 9 | 13.4 | 67 | 100 | 33 | 89.2 | 3 | 8.1 | 1 | 2.7 | 37 | 100 | ||

| 61-87 | 35 | 94.6 | 1 | 2.7 | 1 | 2.7 | 37 | 100 | 11 | 78.6 | 2 | 14.3 | 1 | 7.1 | 14 | 100 | ||

| Nationality | ||||||||||||||||||

| Spanish | 694 | 76.1 | 114 | 12.5 | 104 | 11.4 | 912 | 100 | 0915a | 416 | 76.2 | 80 | 14.7 | 50 | 9.2 | 546 | 100 | 0.8b |

| European Union | 47 | 72.3 | 8 | 12.3 | 10 | 15.4 | 65 | 100 | 17 | 73.9 | 4 | 17.4 | 2 | 8.7 | 23 | 100 | ||

| Non-European Union | 30 | 75.0 | 5 | 12.5 | 5 | 12.5 | 40 | 100 | 10 | 66.7 | 3 | 20.0 | 2 | 13.3 | 15 | 100 | ||

| Employment status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Employed | 650 | 75.1 | 112 | 13.0 | 103 | 11.9 | 865 | 100 | 0.583a | 391 | 77.1 | 71 | 14.0 | 45 | 8.9 | 507 | 100 | 0.232b |

| Unemployed | 65 | 74.7 | 11 | 12.6 | 11 | 12.6 | 87 | 100 | 26 | 70.3 | 6 | 16.2 | 5 | 13.5 | 37 | 100 | ||

| Other | 54 | 84.4 | 5 | 7.8 | 5 | 7.8 | 64 | 100 | 25 | 64.1 | 10 | 25.6 | 4 | 10.3 | 39 | 100 | ||

| Occupational social class | ||||||||||||||||||

| I-II | 503 | 76.9 | 80 | 12.2 | 71 | 10.9 | 654 | 100 | 0.739a | 255 | 74.6 | 52 | 15.2 | 35 | 10.2 | 342 | 100 | 0.646a |

| III-IV | 150 | 72.8 | 30 | 14.6 | 26 | 12.6 | 206 | 100 | 97 | 78.2 | 19 | 15.3 | 8 | 6.5 | 124 | 100 | ||

| V-VI-VII | 77 | 74.8 | 12 | 11.7 | 14 | 13.6 | 103 | 100 | 57 | 76.0 | 9 | 12.0 | 9 | 12.0 | 75 | 100 | ||

| Rental situation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Rent whole house | 330 | 79.7 | 46 | 11.1 | 38 | 9.2 | 414 | 100 | 0.000a | 190 | 78.2 | 32 | 13.2 | 21 | 8.6 | 243 | 100 | 0.014a |

| Shared economy | 296 | 76.3 | 44 | 11.3 | 48 | 12.4 | 388 | 100 | 171 | 77.0 | 28 | 12.6 | 23 | 10.4 | 222 | 100 | ||

| No shared economy | 120 | 70.6 | 30 | 17.7 | 20 | 11.8 | 170 | 100 | 69 | 74.2 | 19 | 20.4 | 5 | 5.4 | 93 | 100 | ||

| Rent room | 21 | 50.0 | 8 | 19.1 | 13 | 31.0 | 42 | 100 | 12 | 48.0 | 8 | 32.0 | 5 | 20.0 | 25 | 100 | ||

| Risk of involuntary mobility | ||||||||||||||||||

| No | 411 | 75.6 | 78 | 14.3 | 55 | 10.1 | 544 | 100 | 0.171a | 261 | 76.8 | 45 | 13.2 | 34 | 10.0 | 327 | 100 | 0.554a |

| Yes | 101 | 75.4 | 12 | 9.0 | 21 | 15.7 | 134 | 100 | 56 | 70.9 | 15 | 19.0 | 8 | 10.1 | 76 | 100 | ||

| Don’t know | 259 | 76.4 | 38 | 11.2 | 42 | 12.4 | 339 | 100 | 126 | 76.4 | 27 | 16.4 | 12 | 7.3 | 159 | 100 | ||

| Dependent variables | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mental well-being | ||||||||||||||||||

| Mental well-being | 305 | 80.3 | 45 | 11.8 | 30 | 7.9 | 380 | 100 | 0.009a | 175 | 78.8 | 33 | 15.1 | 14 | 6.2 | 222 | 100 | 0.142a |

| Mental discomfort | 463 | 73.0 | 82 | 12.9 | 89 | 14.0 | 634 | 100 | 265 | 74.8 | 52 | 14.5 | 40 | 10.8 | 357 | 100 | ||

| Self-rated health | ||||||||||||||||||

| Good | 685 | 76.3 | 112 | 12.5 | 101 | 11.3 | 898 | 100 | 0.441a | 402 | 76.6 | 77 | 14.7 | 46 | 8.8 | 525 | 100 | 0.395a |

| Bad | 86 | 71.7 | 16 | 13.3 | 18 | 15.0 | 120 | 100 | 41 | 69.5 | 10 | 17.0 | 8 | 13.6 | 59 | 100 | ||

EHI: economic housing insecurity; LHI: legal housing insecurity.

p-value of the association between neglected housing insecurity and the study variables using chi-square test (a) or Fisher exact test (b).

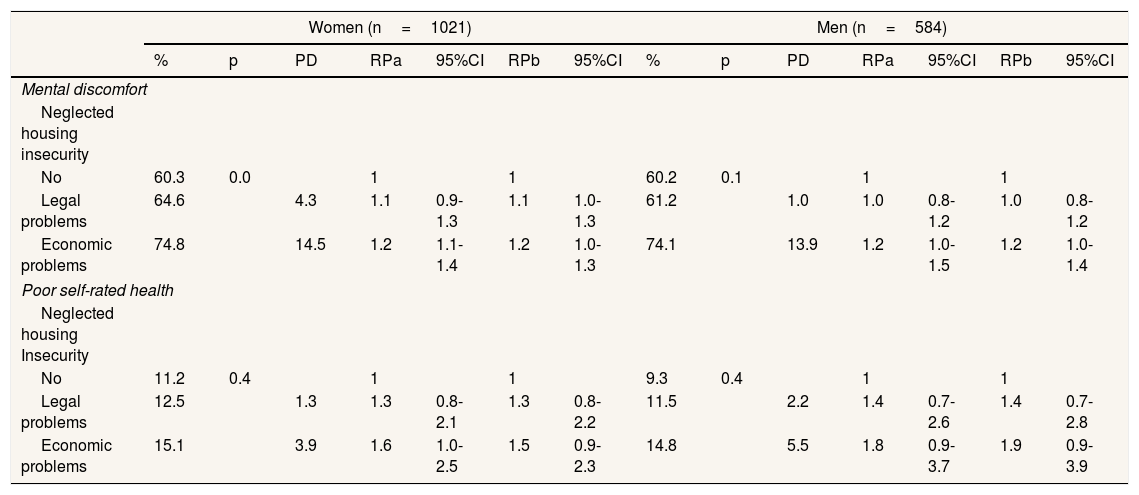

The prevalence of mental discomfort showed a gradient, in which people affected by EHI reported a higher prevalence of mental discomfort (74.8%, women; 74%, men) than people affected by LHI (64.6%, women; 61.2%, men) and these, in turn, had a higher prevalence than those not reporting housing insecurity (60.3%, women; 60.2%, men), with this association being significant in women. Likewise, the PRa (95% confidence interval [95%CI]) of people affected by EHI was 1.2 (1.1-1.4) among women and 1.2 (1.0-1.5) among men compared with non-affected renters; the PRa (95%CI) of people affected by LHI was 1.1 (0.9-1.3) and 1.0 (0.8-1.2), respectively. The same gradient was observed for self-rated health: people affected by EHI reported a higher prevalence of poor self-rated health (15.1%, women; 14.1%, men) than people affected by LHI (12.5%, women; 11.5%, men), who, in turn, reported a higher prevalence than non-affected renters (11.1% women; 9.3%, men). In addition, the PRa (95%CI) of people affected by EHI was 1.6 (1.0-2.5) among women and 1.8 (0.9-3.7) among men compared to individuals without housing insecurity; in those who reported LHI, the PRa (95%CI) was 1.3 (0.8-2.1) and 1.4 (0.7-2.6), respectively.

When adjusting for sociodemographic variables, we found that women with EHI had a mental discomfort PRb of 1.2 (95%CI: 1.0-1.3) and that men with EHI had a PRb of 1.2 (95%CI: 1.0-1.4) compared to those without housing insecurity. The results for persons affected by LHI were not significant, although women affected by LHI showed a possible tendency to being so, with a mental discomfort PRb of 1.1 (95%CI: 1.0-1.3). Regarding self-rated health, women and men under EHI had a higher likelihood of poor health than those without housing insecurity, with a PRb of 1.5 (95%CI: 0.9-2.4) and 1.90 (95%CI: 0.9-3.9), respectively. The same result was observed in women and men under LHI, with a PRb of 1.3 (95%CI: 0.8-2.2) and 1.4 (95%CI: 0.7-2.8), respectively. However, none of these results were statistically significant (Table 4).

Prevalence (%) of poor mental health and poor self-rated health, prevalence difference and prevalence ratio (age-adjusted and adjusted by other sociodemographic variables) in women and men affected by neglected housing insecurity.

| Women (n=1021) | Men (n=584) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | p | PD | RPa | 95%CI | RPb | 95%CI | % | p | PD | RPa | 95%CI | RPb | 95%CI | |

| Mental discomfort | ||||||||||||||

| Neglected housing insecurity | ||||||||||||||

| No | 60.3 | 0.0 | 1 | 1 | 60.2 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Legal problems | 64.6 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 0.9-1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0-1.3 | 61.2 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 | 1.0 | 0.8-1.2 | ||

| Economic problems | 74.8 | 14.5 | 1.2 | 1.1-1.4 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.3 | 74.1 | 13.9 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.5 | 1.2 | 1.0-1.4 | ||

| Poor self-rated health | ||||||||||||||

| Neglected housing Insecurity | ||||||||||||||

| No | 11.2 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | 9.3 | 0.4 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Legal problems | 12.5 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0.8-2.1 | 1.3 | 0.8-2.2 | 11.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 0.7-2.6 | 1.4 | 0.7-2.8 | ||

| Economic problems | 15.1 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 1.0-2.5 | 1.5 | 0.9-2.3 | 14.8 | 5.5 | 1.8 | 0.9-3.7 | 1.9 | 0.9-3.9 | ||

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PD: prevalence difference; PRa: prevalence ratio age-adjusted; PRb: prevalence ratio adjusted by age, social class, employment status, rental situation and risk of involuntary mobility.

This is the first study in Spain that shows the relationship between neglected housing insecurity and mental and physical health among renters. We found that the likelihood of worse health due to neglected housing insecurity was greater in renters affected by EHI, followed by people affected by LHI, both compared to those not affected by housing insecurity. This association were statistically significant in the mental health of renters affected by EHI, both women and men, even after adjustment for socioeconomic and other housing variables.

In this study, mental health was worse in both women and men affected by EHI than in people without housing insecurity. This finding is consistent with previous studies reporting that people who have been forced to leave their dwellings due to economic problems have more mental health problems such an anxiety, depression, stress and lack of control.17,19,20,27 For instance, a previous study with people under different stages of housing insecurity showed that persons who had been forced to leave their dwellings due to financial problems in the last three years were more likely to report recent anxiety attacks.27 Furthermore, two studies conducted in low-income renters with housing insecurity found that they had worse mental health than those without housing insecurity and, also, reported that renters with housing insecurity problems were more likely to delay seeking healthcare due to financial reasons.17,28 In addition, the authors reported that renters with housing insecurity were more likely to experience insecure conditions in other areas such as work, family, food, study, and interpersonal relationships.8,17,28–30 According to Hulse and Saugeres,17 these situations of housing insecurity could contribute to the coexistence of diverse insecurities in people's lives that would be aggravated and produce negative effects on people's health and the generational transmission of this precariousness.

Mental health was slightly worse in women affected by LHI, although this difference was not significant. However, studies from the United Kingdom have reported that being forced to leave housing due to unilateral termination of a valid lease agreement or not being able to renew the lease generates negative psychosocial effects such as lack of control and a loss of the sense of belonging, as people have to move and restart daily routines elsewhere;31,32 these problems of neglected housing insecurity can also lead to an excess responsibility among affected persons, because there is often a lack of legal guarantees in housing policies for people experiencing these underground phenomena.10,33 It has been reported that these elements operate as mechanisms that affect people's mental health.7,17

In this study, self-rated health was worse in persons affected by EHI and LHI than among unaffected individuals. Although these results were not statistically significant, the prevalence ratios were large enough to suggest that greater statistical power would have confirmed this trend. Moreover, other studies of formal evictions have reported an evident negative effect on people's health.28,34 Formal eviction is more traumatic situation which affects health faster than neglected eviction; however, when this latter become repetitive, may reaches the same extent of negative health consequences than formal eviction.27 This association need to be further investigated.

The sample was mainly composed of people aged between 18 and 50 years and with Spanish nationality, which is consistent with observed data of the renter population in the Barcelona Health Survey.35 The distribution of managers and senior professionals in the sample was approximately double that of the Barcelona renter population (∼31%).35 Consequently, if the sample had been more representative of the population of Barcelona, a stronger association would probably have been observed between housing insecurity and health outcomes, because it is well-known that people from disadvantaged groups, such as the manual social class, have worse health status than people from more advantaged groups.19,21 People not identifying with binary gender had more EHI problems and worse health outcomes than women and men. This finding is consistent with studies indicating that transgender and non-conforming gender people experience more discrimination than cisgender people in terms of housing and employment.36 Moreover, worse health outcomes are associated with several forms of discrimination that constrain opportunities and access to basic aspects of life.37 Further in-depth studies are needed to investigate the association in these and other disadvantaged groups (e.g. children and elderly).

One of the limitations of this study is that the sampling method did not allow us to obtain a representative sample of renters in Barcelona and could have introduced selection bias, because it did not include renters affected by neglected housing insecurity but who were unable to participate (e.g., individuals without access to online services, the elderly). Such individuals would likely have even poorer health, and therefore the associations would have been stronger. Second, some categories had a very low sample, and consequently the findings should be interpreted with caution. Third, the magnitude of the association between health outcomes and housing insecurity may have been lost, due to the time interval between exposure and the observation of results; however, self-rated health is a stable indicator of people's health status.25

Despite these limitations, a strength of the study is that we constructed variables that allow an approach to the measurement and visibility of the phenomenon of neglected housing insecurity. This approach could contribute to future studies of invisible evictions, which are currently seriously affecting the Spanish context. In addition, this study is replicable in other contexts since we employed questionnaires that are used in European population studies. Moreover, the collaboration with the Sindicat de Llogateres allowed us to forge alliances between the academic and civil sectors to contribute to change country's housing policies. Finally, and closely related to the use of the online survey platform, another strength of the study is the cost-benefit and time-benefit ratio with which we were able to carry out recruitment.

Neglected housing insecurity is a phenomenon that currently affects many renters. These situations are associated with worse mental health. There is a need for neglected housing insecurity indicators to measure these phenomena and facilitate preventive interventions for this massive but hidden problem. In this regard, the study provides evidence that increases the visibility of this social reality and raises awareness of its implications, thereby contributing to the debate on solutions to this new housing emergency. Further studies are needed to continue investigate the relationship between neglected housing insecurity and renters health.

Housing is recognized as a social determinant of health, affect people's health. To date, only a few studies have addressed the relationship between different types of housing insecurity and poor general and mental health in renters.

What does this study add to the literature?Neglected housing insecurity was associated with worse mental health. In those affected for economic reasons it was significantly associated even after adjusting for socioeconomic and other housing variables

What are the implications of the results?The study provides evidence that increases the visibility of neglected housing insecurity and raises awareness of its effects, thereby contributing to the debate on solutions to this new housing emergency.

Carlos Álvarez Dardet.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsConception and design of the work: C. Vásquez-Vera, J. Carrere, H. Vásquez-Vera and C. Borrell. Analysis and interpretation of the data: C. Vásquez-Vera, J. Carrere and H. Vásquez-Vera. Writing of the article: C. Vásquez-Vera. Approval of the final version for publication: J. Carrere, C. Borrell and H. Vásquez-Vera. To be responsible for ensuring that all aspects of the manuscript have been reviewed and discussed among the authors: C. Vásquez-Vera.

Ac*k**nowledgmentsThe authors thank the Sindicat de Llogateres (Renters Union) for its participation and for access to the study data, the Hidra Cooperative for its contribution to data collection, and the people who participated in the survey.

Ethics approval and consent to participateThe study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Parc de Salut Mar, Barcelona, as part of the project named “Desahucios invisibles” (n.° 2020/9104). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.