The 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health

Más datosThis study aims to measure changes in autonomy in groups that have been given nutrition education by applying the SDT concept.

MethodsThe non-randomized pre-post intervention study design involved 63 teachers in the intervention group and 60 teachers in the control group. Nutrition education by applying the SDT concept and measurement is carried out using the Treatment Self-Regulation Questionnaire (TRSQ).

ResultsThe results showed that there was a significant change in support autonomy in the intervention group (p=0.034) and not in the control group. Controlled variables and amotivation did not show significant differences in the two groups, but changes for the better occurred in the intervention group.

ConclusionThe application of the SDT concept can increase support for autonomy. This is expected to support sustainable behavior change.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) is an important concept in predicting behavior and its consequences.1 This theory has several sub-theories but is widely known as a theory of motivation and self-regulation involving a social context.2 SDT has been widely applied in various fields, including in the world of work, education, sports, and health.3 SDT emphasizes motivation as an important thing in realizing healthy behavior, which in turn will have a positive impact on health.4

SDT was introduced by Deci and Ryan who emphasized behavior change based on their desires.5 SDT distinguishes between types of behavior regulation based on the underlying motivations of the individual, which are divided into intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and no motivation (amotivation). When a behavior follows the basic human need for autonomy, competence, and relatedness, individuals are said to experience intrinsic motivation, which means they have self-determination.6

Intrinsic motivation is associated with controlled or less autonomous behaviors.3 However, SDT distinguishes four types of regulation based on the degree of internalization, which suggests that the more fully internalized and integrated with oneself, the more it will become the basis for autonomous behavior. External regulation refers to individual behavior that is influenced by rewards or threats from outside so that it affects intrinsic motivation. Introjected regulation, namely behavior is determined by the pressure imposed on oneself for avoiding feelings of persistence. Identified regulation refers to the acceptance of the value of behavior as of personal importance. Integrated regulation refers to existing values that are integrated with other aspects of a person, including personal values.3

Autonomy motivation becomes a supporter of carrying out various health behaviors.7 This intrinsic motivation provides an impetus for increased autonomy motivation leading to more effective autonomy motivation.8 One of them is by providing nutrition education.9

Increasing autonomy has been shown to have positive health effects. The systematic review conducted by Teixeira, et al. Shows better autonomy as a predictor for changes in body weight and physical activity.10 This support is also evident in efforts to quit smoking,11 diet,12 and intake of vegetables, fruit.13

Several studies have conducted nutrition education by applying the concept of self-determination theory by comparing the intervention group with the non-intervention group.14 This study aims to compare the interventions that have been carried out by the government, namely the provision of balanced nutrition leaflets with balanced nutrition modules by applying the concept of self-determination theory.

MethodsA pre-post interventional study was carried out among civil servant teachers in Makassar City. A complete description of the research design and data collection has been described in previously published studies.15 The questionnaire used in this study was revalidated TSRQ16 in Indonesian text with reliability (Cronbach alpha) of 0.75615. The modules are prepared based on the balanced nutrition guidelines issued by the Ministry of Health.17 The development of modules is through literature reviews and FGDs conducted at one of the schools in Makassar City. The study uses Calendar and Poster.

The intervention activity was carried out once/month for 4 months. Following the SDT concept, each intervention activity will implement the following: (1) this change “can” be done, not “must” be done, (2) emphasizes that attendance at this seminar is important, (3) provide respondents with several choices of methods for changing behavior, (4) support every decision of the respondent, while still providing an overview of the choice of behavior and the results to be obtained, (5) encourage participants to adapt their choices to their lifestyle (6) give positive feedback, to all their decisions.

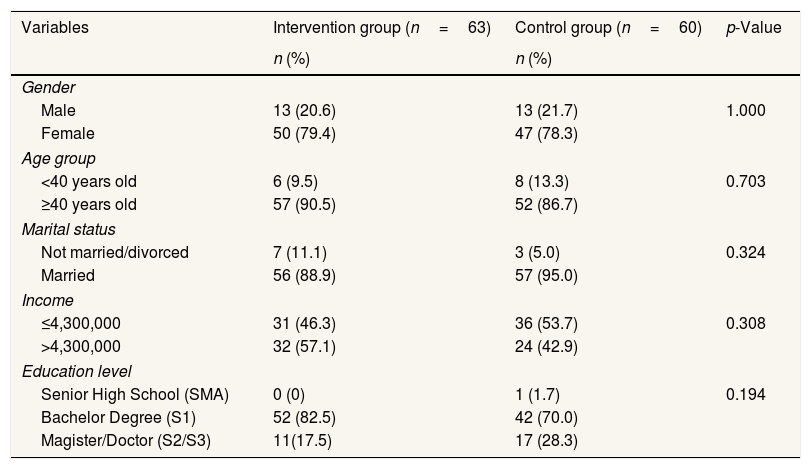

ResultDemographic characteristics can be seen from the variables of gender, age group, marital status, income, and education level. Based on the results of the bivariate analysis on demographic characteristics variables, it shows that there is no significant difference between the intervention group and the control group (p>0.05). This means that both groups are in the same condition before the intervention (Table 1).

Demographic characteristics of the intervention group and the control group.

| Variables | Intervention group (n=63) | Control group (n=60) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 13 (20.6) | 13 (21.7) | 1.000 |

| Female | 50 (79.4) | 47 (78.3) | |

| Age group | |||

| <40 years old | 6 (9.5) | 8 (13.3) | 0.703 |

| ≥40 years old | 57 (90.5) | 52 (86.7) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Not married/divorced | 7 (11.1) | 3 (5.0) | 0.324 |

| Married | 56 (88.9) | 57 (95.0) | |

| Income | |||

| ≤4,300,000 | 31 (46.3) | 36 (53.7) | 0.308 |

| >4,300,000 | 32 (57.1) | 24 (42.9) | |

| Education level | |||

| Senior High School (SMA) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | 0.194 |

| Bachelor Degree (S1) | 52 (82.5) | 42 (70.0) | |

| Magister/Doctor (S2/S3) | 11(17.5) | 17 (28.3) | |

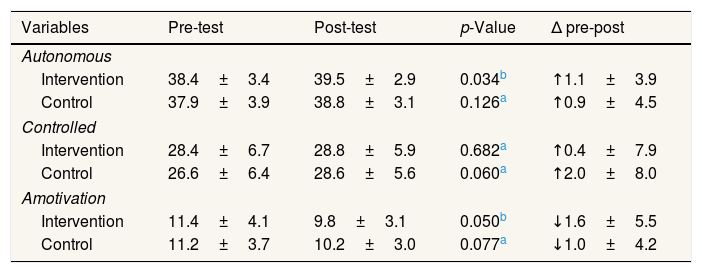

Table 2 shows that in the autonomy variable of the intervention group, the mean value before the intervention was 38.4±3.4 and after the intervention was 39.5±2.9 with a value of p=0.034. Whereas in the control group, the mean value before the intervention was 37.9±3.9 and after the intervention was 38.8±3.1 with a value of p=0.126. The control variable in the intervention group, the mean value before the intervention was 28.4±6.7, and after the intervention was 28.8±5.9 with p-value=0.682. Whereas in the control group, the mean value before the intervention was 26.6±6.4 and after the intervention was 28.6±5.6 with p-value=0.060. Amotivation variable in the intervention group, the mean value before the intervention was 11.4±4.1, and after the intervention was 9.8±3.1 with p-value=0.050. Whereas in the control group, the mean value before the intervention was 11.2±3.7 and after the intervention was 10.2±3.0 with a value of p=0.077. There is no difference in changes in autonomy, control, and motivation in both the intervention group and the control (p>0.05).

Differences in autonomy, controlled and amotivation changes before and after the intervention in the group that received the PGS module and educational tools compared to the group that only received PGS pamphlets.

| Variables | Pre-test | Post-test | p-Value | Δ pre-post |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous | ||||

| Intervention | 38.4±3.4 | 39.5±2.9 | 0.034b | ↑1.1±3.9 |

| Control | 37.9±3.9 | 38.8±3.1 | 0.126a | ↑0.9±4.5 |

| Controlled | ||||

| Intervention | 28.4±6.7 | 28.8±5.9 | 0.682a | ↑0.4±7.9 |

| Control | 26.6±6.4 | 28.6±5.6 | 0.060a | ↑2.0±8.0 |

| Amotivation | ||||

| Intervention | 11.4±4.1 | 9.8±3.1 | 0.050b | ↓1.6±5.5 |

| Control | 11.2±3.7 | 10.2±3.0 | 0.077a | ↓1.0±4.2 |

In Table 2 it can also be seen that the changes that have occurred are seen from the results of the pre-test and post-test. There is an increase in the post-test score on the aspect of autonomy regulation. In the controlled aspect, there was also an increase but the p-value was not significant. Meanwhile, in the amotivation aspect, there was a decrease although it was also not significant based on the results of the statistical test.

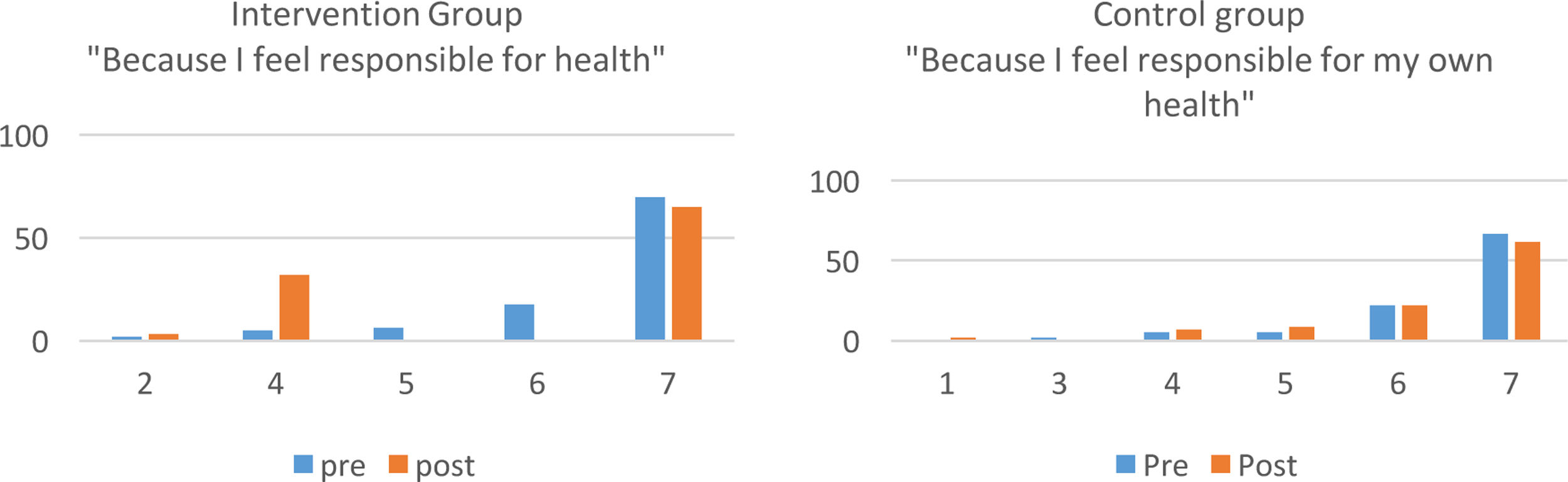

Furthermore, the participants’ responses based on the question items from the TRSQ scale during the pre-test and post-test were described descriptively, particularly in the aspect of autonomy regulation which experienced a significant increase. Fig. 1 shows that concerning perceptions of personal responsibility for health, there is not much difference between the two groups. It appears that some participants from the intervention group became more or less consistent with this view because the responses were more spread out over several numerical levels. Besides, if you look at the responses that strongly agree with the statement, the number of responses decreased at the post-test in the intervention group although not much.

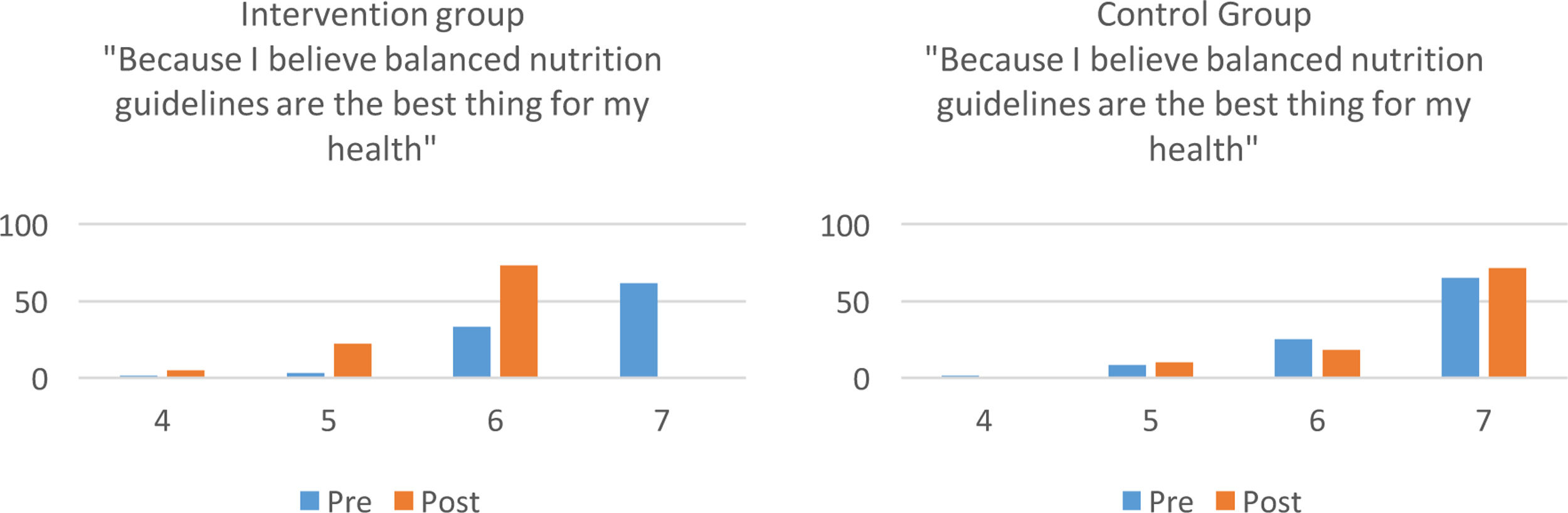

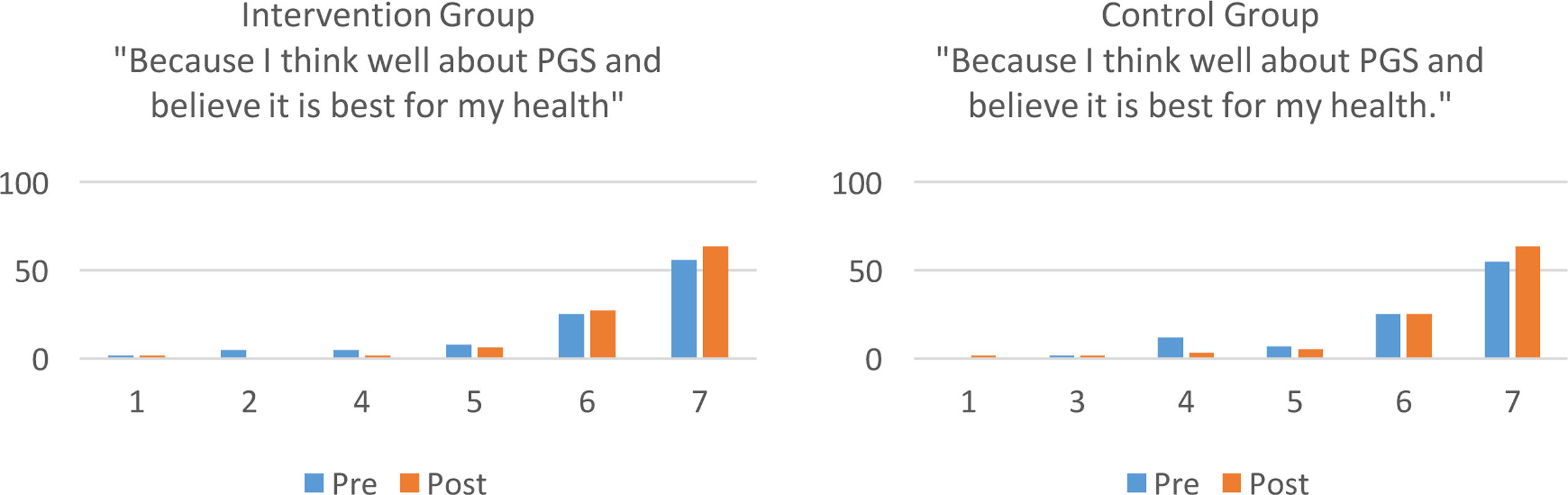

Fig. 2 shows the response patterns of the two groups which do not differ much. Nonetheless, in the intervention group, the belief that balanced nutrition guidelines were best for individual health was seen to improve significantly after the intervention. Furthermore, there is no significant difference from Fig. 3 which shows that beliefs about PGS as the best program for health do not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups. The post-test results also showed significant positive changes in both groups.

DiscussionThe results showed that there was a significant difference in autonomy in the group given nutrition education by applying the concept of self-determination theory compared to the control group (p=0.034 vs. 0.126). This shows that the SDT concept-based nutrition education program can indeed improve participant self-regulation in which participants become more intrinsically motivated or show more autonomy to improve the quality of their health. One of the dominant areas o applied research in SDT is research in the field of health behaviors which aims to promote and direct a person to adopt healthy behaviors, including those related to a healthy diet, regular physical activity, prevention of obesity, and cardiovascular disease and reducing tobacco consumption.2 Several studies have also demonstrated the role of autonomous self-regulation and autonomy support in promoting greater motivation and persistence in physical activity, and SDT has been applied in physical education, health promotion, and formation settings around the world.2

This study is also in line with research conducted by Rubak, et al. On patients with type 2 diabetes, which showed an increase in autonomy support after motivation.18 The education module was compiled, applying the SDT concept developed by Deci and Ryan.5 This concept emphasizes the autonomy aspect, namely changes based on their desires, without coercion from outside, thus the source of behavior change comes from within the individual himself. Several studies related to health problems have been conducted and have shown significant results in behavior change.8

It is important to emphasize changes in autonomy in self-regulation. Changes in behavior that are based on the desire of oneself have an impact on the continuity of these changes in behavior, which are continuously carried out. This is very important, especially in promoting health behavior.3 In the “wheel of behavioral change” method, one of the most important aspects of behavior change is motivation.9 In this self-determination theory, it is known that there are three basic human needs, namely autonomy, competence, and connectedness (relatedness). Thus, if individual behavior can meet these needs, individuals tend to be intrinsically motivated. Thus, fostering autonomy essentially helps to promote intrinsic motivation. Autonomy support provided by doctors or other practitioners can predict patient autonomy and perceived competence, which in turn predicts changes in health behavior that are maintained, as well as the concrete fulfillment of certain health indicators.2

In each meeting, the facilitator provides examples of practices that can be done. Providing relaxation practices after sitting for several hours, showing examples of local fruits that can be found at any time, providing samples of packaging materials, and how to read labels are some of the practices practiced during the intervention. The facilitator in this case can also play a role in improving the relatedness aspect because the participants feel supported. Likewise with the presence of other people who participated in the same program. Even though this is controlled regulation, as explained in the introduction, extrinsic motivation can become more intrinsic when finally the perceived relatedness makes the behavior identified as acceptable behavior and integrated with personal beliefs. Moreover, it is supported by the sense of competence that is possessed because of the nutritional education process that is provided.

Effective self-regulation is the foundation of healthy psychological functioning. People who fail in self-regulation will experience control over their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.19 A meta-analysis of the mechanism of self-regulation in health behavior change 2006–2017 compared the accuracy of the components of self-regulation intervention by looking at the level of behavior change. Meta-analyzes that focus on components of the intervention have been identified as successful, such as the presence of personal feedback, goal setting, and self-monitoring. Nonetheless, these successes are inconsistent as each only works for some health behaviors and with specific populations.20

ConclusionThis study shows that the application of SDT in nutrition education to promote health behavior with increased nutrition can increase autonomy support. This also shows that interventions with the SDT concept can improve self-regulation.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health (ICOS-PH 2020). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.