The main objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of heavy drinking on alcohol-related injuries.

Material and methodsWe carried out an open cohort study among university students in Spain (n=1,382). Heavy drinking and alcohol-related injuries were measured by administrating AUDIT questionnaires to every participant at the ages of 18, 20, 22 and 24. For data analysis we used a Multilevel Logistic Regression for repeated measures adjusting for consumption of alcohol and cannabis.

ResultsThe response rate at the beginning of the study was 99.6% (1,369 students). The incidence rate of alcohol-related injuries was 3.2 per 100 students year. After adjusting for alcohol consumption and cannabis use, the multivariate model revealed that a high frequency of heavy drinking was a risk factor for alcohol-related injuries (Odds Ratio=3.89 [95%CI: 2.16 – 6.99]). The proportion of alcohol-related injuries in exposed subjects attributable to heavy drinking was 59.78% [95%CI: 32.75 – 75.94] while the population attributable fraction was 45.48% [95%CI: 24.91 – 57.77].

ConclusionWe can conclude that heavy drinking leads to an increase of alcohol-related injuries. This shows a new dimension on the consequences of this public concern already related with a variety of health and social problems. Furthermore, our results allow us to suggest that about half of alcohol-related injuries could be avoided by removing this consumption pattern.

El objetivo principal del estudio es evaluar el efecto del consumo intensivo de alcohol sobre las lesiones relacionadas con esta droga.

Material y métodosSe ha realizado un estudio de cohorte abierta entre universitarios en España (n=1.382). El consumo intensivo y las lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol se midieron mediante la administración del cuestionario AUDIT a cada uno de los participantes a las edades de 18, 20, 22 y 24 años. Para analizar los datos se utilizó la Regresión Logística Multinivel para medidas repetidas ajustando por consumo de alcohol y de cannabis.

ResultadosLa tasa de respuesta al comienzo del estudio fue 99,6% (1.369 estudiantes). La tasa de incidencia de lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol fue de 3,2 por 100 estudiantes año-1. Tras ajustar por consumo de alcohol y de cannabis, el modelo multivariante revela que la alta frecuencia de consumo intensivo fue un factor de riesgo para las lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol (Odds Ratio=3,89[95%CI:2,16 – 6,99]). La proporción de lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol en expuestos atribuible al consumo intensivo fue 59.78% [95%CI: 32.75 – 75.94] mientras que la fracción atribuible poblacional fue 45.48% [95%CI: 24.91 – 57.77].

ConclusiónPodemos concluir que el consumo intensivo conduce a un aumento de las lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol. Esto muestra una nueva dimensión de las consecuencias de esta preocupación social que ya se ha relacionado con variedad de problemas sociales y de salud. Además los resultados nos permiten sugerir que aproximadamente la mitad de las lesiones relacionadas con el alcohol podrían evitarse eliminando este patrón de consumo.

In Spain, alcohol consumption is part of the culture. The traditional pattern consists of regular consumption associated with meals, family celebrations, and social events.1-2 However, this drinking pattern is increasingly being replaced among young people by intermittent weekend consumption, with episodes of heavy drinking.3 Heavy drinking is characterized by the consumption of large amounts of alcohol in a short time, and brings blood alcohol concentrations to .08g/dl or above. In Spain, heavy drinking is generally practiced outdoors, at public spaces where large numbers of youths meet. Noise, littering, and even destruction of public property are the main negative consequences attributed by society to this drinking pattern.4 Hospital admissions due to alcohol poisoning are other consequences, often out of public sight. However, in Spain the perceived risk of heavy drinking is quite low compared to the perceived risk of the consumption of other drugs, even in small doses.3

Chronic alcohol abuse has well-established effects on morbidity and mortality.5,6,7 However, heavy drinking may also increase the risk of alcohol-related health issues.8 A recent transversal study has estimated that alcohol-related injuries are more frequent among university students who indulge in a heavy drinking pattern of consumption than in those who do not participate in this pattern of drinking (43% compared with 10% occurrence of alcohol-related injury).9 Even though there are important differences between populations, we think this association can also be apply in our context.

To date, no follow-up studies have examined the association between heavy drinking and alcohol-related injuries adjusted for consumption of alcohol in Mediterranean countries.10 Therefore the aim of this study is to evaluate the effect of heavy drinking on the incidence of alcohol-related injuries.

Material and methodsDesign, Population and SampleAn open cohort analysis was conducted within the framework of a cohort study designed to evaluate the neuropsychological and psychophysiological consequences of alcohol use. The study was carried out between November 2005 and May 2012 among students at the University of Santiago de Compostela (Spain). We performed a cluster sampling. From each one of the 33 university schools, at least one of the freshman year classes was randomly selected (a total of 53 classes). The number of classes selected on each university school was proportional to its number of students. All students present in the class on the day of the survey were invited to participate in the study (n=1,382). Abstinent subjects were excluded from the study. The study was approved by the university ethics committee (October 2004).

Data Collection ProceduresParticipants were evaluated via a self-administered questionnaire in the classroom in November 2005 and again in November 2007. Students that provided their phone number were further evaluated by phone at 4.5- and 6.5-year follow-up. On all four occasions, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related injuries were measured using the Galician validated version of the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT).11,12 We decided to use the AUDIT because it is widely considered one of the best screening tests for alcohol abuse; it’ transnational; it has been use with college population and it has also been use specifically for measuring heavy drinking. At baseline and at the 2-year follow-up, participants responded to additional questions about age of onset of alcohol consumption and about cannabis consumption.

Definition of variablesDependent variableAlcohol-related injuries at 20, 22 and 24 years old. Dichotomous variable. Question 9 of the AUDIT: “Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking? No; Yes, but not during the last year; and Yes, during the last year”.

Independent variablesHeavy drinking at 18, 20, and 22 years old. Question 3 of the AUDIT: “How often do you have 6 or more alcoholic drinks on a single occasion? Never; Less than once a month; At least once a month; At least once a week; Daily or Almost daily”. The categories At least once a month; At least once a week and Daily or Almost daily were recategorized to More frequently.

Cannabis consumption and number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day (Question 2 of the AUDIT) were also considered as independent variables, because it is known that both variables can result in a lower risk perception and decreased attention, which may consequently lead to injury. Adjusting by both variables, we can therefore identify the specific effect associated to heavy drinking. Frequency of alcohol consumption (Question 1 of the AUDIT) was also considered in order to remove the abstinent subjects.

Cannabis consumption at 18, and 20 years old. This variable was measured with the question “Do you consume cannabis when you go out? Never; Sometimes; Most of the times; Always”. The categories Most of the times and Always were recategorized to Usually.

Number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day at 18, 20, and 22 years old. Question 2 of the AUDIT: “How many alcoholic drinks do you have on a typical day when you are drinking? 1 or 2; 3 or 4; 5 or 6; 7 to 9; 10 or more”.

Frequency of alcohol consumption at 18, 20, and 22 years old. Question 1 of the AUDIT: “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? Never; Monthly or less; Two to four times a month; Two to three times a week; Four or more times a week”.

Statistical analysisThe follow-up was structured in 3 periods: 11/2005- 11/2007 (2 years); 11/2007 – 05/2010 (2.5 years); and 05/2010 – 05/2012 (2 years). Because of the open cohort design of the study, the conditions of subjects may have changed during follow-up. While the 9th AUDIT question refer to alcohol related injuries suffered in the past, the independent variables about alcohol consumption and cannabis consumption were referred about the present. Therefore, the variable “alcohol-related injuries” measured in 11/2007, 05/2010, and 05/2012 was considered as the effect of both the number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day (Question 2 of the AUDIT) and the heavy drinking (Question 3 of the AUDIT) having occurred in 11/2005, 11/2007 and 05/2010 respectively. Since we have only two measures of cannabis use (2005 and 2007), we considered the alcohol-related injuries in 11/2007 as the effect of the cannabis use in 11-2005 and both alcohol related injuries at 05/2010 and 05/2012 as the effect of cannabis use at 11/2007. At each stage of the study the subjects than answered Never to the first question of the AUDIT were excluded.

We used multilevel logistic regression for repeated measures to obtain adjusted Odds Ratios for Alcohol-related injuries. The university school and the class were considered as randomized variables. The follow-up time was included as an offset term. Data were analyzed using Generalized Linear Mixed Models from the SPSS 20.0.

Finally, in order to calculate the population impact measures, we considered the following formulas:13 (1) To calculate the proportion of alcohol related injuries in exposed subjects attributable to heavy drinking 1-1/RR; and (2) To calculate the population attributable fraction pc-pc/RR, being pc the prevalence of exposition in ill subjects. For both formulas, RR was calculated dichotomizing the Heavy drinking variable (yes/no).

ResultsThe response rate at the beginning of the study was 99.6%. The mean follow-up period was 4.57 years and the median follow-up period 4.50 years. At baseline 72.8% of the subjects were female and 76.0% lived outside their parents home. The prevalence of cannabis use was 20.8%. The mean age of onset of alcohol consumption was 16.0 [95%CI: 16.0; 16.1]. On proportion of 18.8% of the subjects started drinking alcohol after 16 years old, 38.3% at 16, 24.4% at 15, and 18.4% before 15 years of age.

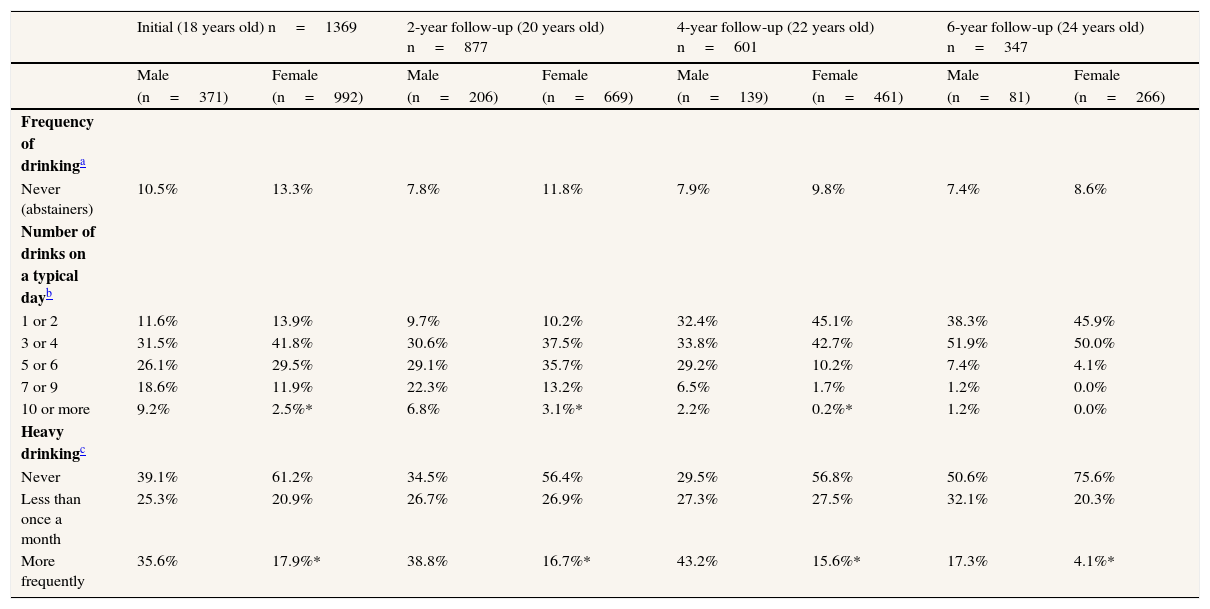

In total, 117 cases of alcohol-related injuries were detected in a follow-up period of 3,706.00 years. The incidence rate of alcohol-related injuries during the follow-up was 3.2 per 100 students year-1 [95%CI: 2.58; 3.73]. The proportion of subjects who engaged in heavy drinking is significantly greater for male students in every period. This proportion decreased significantly at the age of 24 for both genders. The number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day is also greater for male students, except in the last period. This number also decreased significantly over the study period for both genders. (Table 1).

Consumption of alcohol by gender.

| Initial (18 years old) n=1369 | 2-year follow-up (20 years old) n=877 | 4-year follow-up (22 years old) n=601 | 6-year follow-up (24 years old) n=347 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| (n=371) | (n=992) | (n=206) | (n=669) | (n=139) | (n=461) | (n=81) | (n=266) | |

| Frequency of drinkinga | ||||||||

| Never (abstainers) | 10.5% | 13.3% | 7.8% | 11.8% | 7.9% | 9.8% | 7.4% | 8.6% |

| Number of drinks on a typical dayb | ||||||||

| 1 or 2 | 11.6% | 13.9% | 9.7% | 10.2% | 32.4% | 45.1% | 38.3% | 45.9% |

| 3 or 4 | 31.5% | 41.8% | 30.6% | 37.5% | 33.8% | 42.7% | 51.9% | 50.0% |

| 5 or 6 | 26.1% | 29.5% | 29.1% | 35.7% | 29.2% | 10.2% | 7.4% | 4.1% |

| 7 or 9 | 18.6% | 11.9% | 22.3% | 13.2% | 6.5% | 1.7% | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| 10 or more | 9.2% | 2.5%* | 6.8% | 3.1%* | 2.2% | 0.2%* | 1.2% | 0.0% |

| Heavy drinkingc | ||||||||

| Never | 39.1% | 61.2% | 34.5% | 56.4% | 29.5% | 56.8% | 50.6% | 75.6% |

| Less than once a month | 25.3% | 20.9% | 26.7% | 26.9% | 27.3% | 27.5% | 32.1% | 20.3% |

| More frequently | 35.6% | 17.9%* | 38.8% | 16.7%* | 43.2% | 15.6%* | 17.3% | 4.1%* |

a Question 1 of the AUDIT: “How often do you have a drink containing alcohol?”

b Question 2 of the AUDIT: “How many alcoholic drinks do you have on a typical day when you are drinking?”

c Question 3 of the AUDIT: “How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion?”

* Chi-square p-value<0.05.

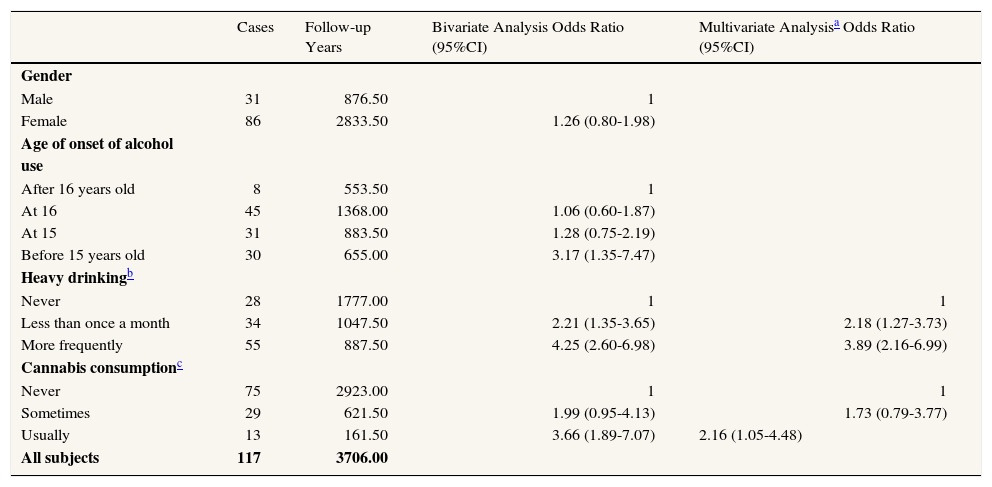

After adjusting for number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day, the multivariate model revealed that a high frequency of heavy drinking and cannabis consumption were risk factors for alcohol-related injuries (Table 2). The number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day was not a significant variable, but it stayed as a part of the definitive model because it was a confounding variable.

Factors associated with the incidence of alcohol-related injuries during the six year follow-up period. Multilevel logistic regression for repeated measures.

| Cases | Follow-up Years | Bivariate Analysis Odds Ratio (95%CI) | Multivariate Analysisa Odds Ratio (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 31 | 876.50 | 1 | |

| Female | 86 | 2833.50 | 1.26 (0.80-1.98) | |

| Age of onset of alcohol use | ||||

| After 16 years old | 8 | 553.50 | 1 | |

| At 16 | 45 | 1368.00 | 1.06 (0.60-1.87) | |

| At 15 | 31 | 883.50 | 1.28 (0.75-2.19) | |

| Before 15 years old | 30 | 655.00 | 3.17 (1.35-7.47) | |

| Heavy drinkingb | ||||

| Never | 28 | 1777.00 | 1 | 1 |

| Less than once a month | 34 | 1047.50 | 2.21 (1.35-3.65) | 2.18 (1.27-3.73) |

| More frequently | 55 | 887.50 | 4.25 (2.60-6.98) | 3.89 (2.16-6.99) |

| Cannabis consumptionc | ||||

| Never | 75 | 2923.00 | 1 | 1 |

| Sometimes | 29 | 621.50 | 1.99 (0.95-4.13) | 1.73 (0.79-3.77) |

| Usually | 13 | 161.50 | 3.66 (1.89-7.07) | 2.16 (1.05-4.48) |

| All subjects | 117 | 3706.00 |

In relation to population impact measures, our study found that the proportion of alcohol related injuries in exposed subjects attributable to heavy drinking was 59.78 [95%CI: 32.75; 75.94]. The population attributable fraction was 45.48 [95%CI: 24.91; 57.77].

DiscussionThe findings of this study demonstrate a strong correlation between heavy drinking and the incidence of alcohol-related injuries, especially for heavy drinking that happens more than once a month. This effect persisted after adjusting for confounding variables including number of alcoholic drinks on a typical day and cannabis consumption.

Some regions of the human brain continue their development during adolescence and youth, which explains why an excessive consume of alcohol at these ages can affect brain plasticity and maturation, with long term consequences on behavior.14 Imaging techniques show that high doses of alcohol decrease the activity of some brain regions involved in error processing, prevention of compulsive actions, behavior regulation, cognition, and coordination of motor activities, which may explain the higher incidence of alcohol-related injuries.15 Several studies have indicated that intermittent alcohol consumption (heavy drinking) may constitute a greater risk to neurocognitive functioning than regular alcohol consumption.16

In relation to cannabis consumption, the results of the study are consistent with those of previous studies.17 There was no association between alcohol-related injuries and gender. This novelty should be studied in subsequent investigations and needs to be considered at the time of implementing preventive measures for avoiding this drinking pattern.

Our results largely confirm what is known in the literature, their especial contribution being the population studied: youth of a society with the Mediterranean drinking pattern in which heavy drinking is spreading. Specifically the proportion of alcohol-related injuries in population attributable to heavy drinking was nearly 50%, which means a potential reduction of almost half of these injuries by avoiding this consumption pattern.

With respect to the limitations of the study, the incidence of injuries related to alcohol consumption was probably underestimated for the following reasons: (1) subjects could have forgotten injuries (memory bias) (2) subjects may have minimized the role of alcohol in the occurrence of injuries (3) subjects were not asked how many injuries they had suffered, just whether they had suffered an injury (4) when subjects responded “Yes, but not in the last year” we only considered that this was a new instance of injury if the subject had not reported a previous alcohol-related injury in a previous AUDIT.

Given the study results preventive measures should be implemented. It must be taken into account that in the social context of the study area there might be strong opposition to the application of effective measures to diminish the consumption of alcohol: (1) Spanish society is quite permissive about alcohol use; 3-18 and (2) Spain is one of the largest wine producers in the world and has an important tourism industry built around nightlife.2

Preventive measures should aim to implement programs based on models of social influence, working on normative beliefs, social skills, rules of behavior, motivation, self-control19 and introducing community programs with the participation of families, schools, and civic associations.

Specific activities aimed guard towars college students have proven effective in reducing heavy drinking and its consequences.20-21 At Spain, brief local interventions with young patients in emergency or primary care have shown a reduction in future consumption, risk of hospital readmission, driving under the influence of alcohol, and related alcohol issues.22-23 These interventions should be generalized.

Other policy measures that could be taken are: (1) Rigor in the compliance with alcohol related laws (currently there is a permissive attitude) as: Minimum legal age for alcohol consumption (18 years); ban on the sale of alcohol to under 18. (2) Expand the ban on drinking in public places all statewide, blame the alcohol dealers, specific licenses for selling alcohol where is not consumed, more limitations for advertising and promotion of alcoholic drinks (usually focused in young people), more restrictive measures concerning supply, sale and consumption. And (3) raising taxes and prices of alcoholic drinks, one of the most effective measures in young people. It is estimated that an increase of 10% prices in Europe prevents or avoids 9000 deaths, with the added benefits of 13 million euros deposited at the state taxes. 24,25

We can conclude that heavy drinking leads to an increase of alcohol-related injuries. This shows a new dimension on the consequences of this public concern already related with a variety of health and social problems. Furthermore, our results allow us to suggest that about half of alcohol-related injuries could be avoided by removing this consumption pattern. Future studies should aim at applying the study to other populations and other heavy drinking consequences. Studies about preventive measures, their performance and effectiveness, are also needed.

There are evidences of an association between alcohol consumption and alcohol-related injuries. However, the social consequences of heavy episodic drinking are less well known and may vary among countries, depending on sociodemographic characteristics and the role that alcohol plays in different cultures.

What does this study add to the literature?The findings from this study show the existence of a strong relation between Heavy episodic drinking and the incidence of alcohol-related injuries in our country. With the adoption of policies for removing this consumption pattern about half of alcohol-related injuries could be avoided.

Carlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Author contributionsStudy conception and design: Caamaño-Isorna, Cadaveira, Corral, Rodríguez Holguín

Acquisition of data: Juan-Salvadores and DoalloAnalysis and interpretation of data: Moure-Rodríguez

Drafting of manuscript: Juan-Salvadores, Doallo, Caamaño-Isorna, Cadaveira, Corral, Rodríguez Holguín, Moure-Rodríguez

Critical revision: Juan-Salvadores, Doallo, Caamaño-Isorna, Cadaveira, Corral, Rodríguez Holguín, Moure-Rodríguez

FundingThe study was funded by a grant from the Spanish National Plan on Drugs (N.P.D) (2005/PN014) and by a grant from MICINN PSI2011-22575.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.