We read with great interest the article Bullying among schoolchildren: differences between victims and aggressors, recently published in Gaceta Sanitaria.1 Motivated by this study, we would like to share information about the characteristics of victims and aggressors of bullying in Peru after an extensive literature search about this underexplored topic in our country and attempt some comparisons versus Spain as well as some concluding remarks and recomendations.

Bullying in Peru, as very likely in Spain, is a hidden and yet latent phenomenon. Moreover, it varies across regions in our country and profiles might be different than what is found in Spain. In a study conducted in an urban Lima school in 2007, victims usually had fewer friends, spent more time alone at recess and exhibited decreased self-confidence than non-victims.2 Similarly, another study conducted in in 2009 found that adolescents with any physical defects are more prone to being bullied, being excluded by aggressors and experience discriminative behaviors that cause impaired social image of the victim and generate rivalries with peers.3 In Peruvian rural areas adolescent victims tend to be picked on by peers, be very quiet, fearful and considered small and weak and not to respond to attacks.2–4

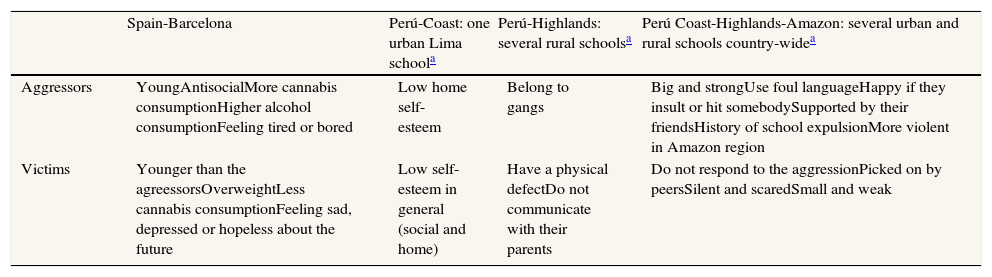

On the other hand, the aggressors’ profile also differs from the ones in Spain. In a study conducted in 2009,3 they self-considered big and strong, use foul language frequently and were happy when insulting or beating their peers. They also tend to be surrounded by groups that support them, and have a history of having been expelled from other schools.4 Aggressors have no overall self-esteem issues because they are usually physically stronger, and are considered “popular,” but they had a lower score on home self-esteem because they come from families with difficulties.2 Moreover, another study noted the presence of gangs or gang friends in school environment as risk factors for bullying.3 A summary of the main characteristics of victims and aggressors in Peruvian studies is presented in Table 1.

Key characteristics of victims and aggressors highlighted in Peruvian studies about bullying in contrast to Spain.

| Spain-Barcelona | Perú-Coast: one urban Lima schoola | Perú-Highlands: several rural schoolsa | Perú Coast-Highlands-Amazon: several urban and rural schools country-widea | |

| Aggressors | YoungAntisocialMore cannabis consumptionHigher alcohol consumptionFeeling tired or bored | Low home self-esteem | Belong to gangs | Big and strongUse foul languageHappy if they insult or hit somebodySupported by their friendsHistory of school expulsionMore violent in Amazon region |

| Victims | Younger than the agreessorsOverweightLess cannabis consumptionFeeling sad, depressed or hopeless about the future | Low self-esteem in general (social and home) | Have a physical defectDo not communicate with their parents | Do not respond to the aggressionPicked on by peersSilent and scaredSmall and weak |

In conclusion, bullying is a complex social phenomenon that changes across environments, cultures and countries and even within a country as exhibited in Peruvian studies. All these factors might potentially shape different profiles for both victims and aggressors and this point out the need to establish prevention programs tailored to each specific context as well as to the specific needs of the involved subjects.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have contributed substantially to the conception, drafting the manuscript and critical revision of the content.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestsNone.