To conduct a stratified cost-utility analysis of total versus partial hip arthroplasty as a function of clinical subtype.

MethodAll cases of this type of intervention were analysed between 2010 and 2016 in the Basque Health Service, gathering data on clinical outcomes and resource use to calculate the cost and utility in quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) at individual level. The statistical analysis included applying the propensity score to balance the groups, and seemingly unrelated regression models to calculate the incremental cost-utility ratio and plot the cost-effectiveness plane. The interaction between age group and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) risk class was assessed in the multivariate analysis.

ResultsThe study identified 5867 patients diagnosed with femoral neck fracture, of whom 1307 and 4560 were treated with total and partial hip arthroplasty, respectively. In the cost-utility analysis based on the seemingly unrelated regression, total hip arthroplasty was found to have a higher cost and higher utility (2465€ and 0.42 QALYs). Considering a willingness-to-pay threshold of €22,000 per QALY, total hip arthroplasty was cost-effective in the under-80-year-old subgroup. Among patients above this age, hemiarthroplasty was cost-effective in ASA class I-II patients and dominant in ASA class III-IV patients.

ConclusionsSubgroup analysis supports current daily clinical practice in displaced femoral neck fractures, namely, using partial replacement in most patients and reserving total replacement for younger patients.

Realizar un análisis de coste-utilidad de la prótesis total de cadera frente a la prótesis parcial.

MétodoSe analizaron todos los casos intervenidos desde 2010 hasta 2016 en el Servicio Vasco de Salud, recogiendo resultados clínicos y uso de recursos para calcular individualmente el coste y la utilidad en años de vida ajustados por calidad (AVAC). El análisis estadístico incluyó el pareamiento por puntaje de propensión para balancear los grupos y modelos de regresión aparentemente no relacionados para calcular la razón de coste-utilidad incremental y el plano de coste-efectividad. La interacción de grupo de edad y riesgo según la American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) se incluyó en el análisis multivariante.

ResultadosSe identificaron 1307 pacientes con prótesis total y 4560 con prótesis parcial. Al hacer el análisis de coste-utilidad con modelos de regresión aparentemente no relacionados el resultado fue mayor coste y mayor utilidad para la prótesis total (2465 € y 0,42 AVAC). Para un umbral de 22.000 € por AVAC, la prótesis total fue coste-efectiva en el subgrupo de menores de 80 años. En el grupo de mayores de 80 años la parcial fue coste-efectiva en los casos con riesgo ASA I-II y dominante en los ASA III-IV.

ConclusionesEl análisis de subgrupos ratifica la práctica clínica habitual en las fracturas de cuello de fémur desplazadas de intervenir a la mayoría de los pacientes mediante prótesis parcial y reservar la prótesis total para los pacientes más jóvenes.

Hip fractures are currently a public health problem, evidenced by a high and growing incidence. In Spain they increased from 26,834 in 2000 to 35,997 in 2012, with the respective impact in terms of mortality that this entails, as one in six patients dies during the first year.1,2 Further, those who survive experience a significant reduction in quality of life and autonomy measured by EuroQol-5D-3L (EQ-5D) and Barthel index, respectively.2 As the incidence is expected to increase in the near future due to population ageing, such a scenario will be associated with an even greater burden in terms of both, loss of health and loss of social and healthcare costs.1,2 In Europe, with over 610,000 cases, hip fractures accounted for more disability-adjusted life years lost than many common cancers.3 At the same time, their management entails high costs to address surgical care, medical care, and rehabilitation treatment.4 The social impact is also noteworthy, as denoted by the high percentage of community-dwelling patients which cannot be discharged to home.5

Displaced femoral neck fractures usually require replacement, most commonly with partial hip replacement, also called hip hemiarthroplasty (HA), given that it is less aggressive, achieves similar results in terms of health-related quality of life and is less expensive than total hip arthroplasty (THA).4,6 THA tends to be indicated for younger patients who have a better quality of life and longer life expectancy, as this type of replacement is more durable and associated with greater mobility.7 Nonetheless, patients of advanced age with good quality of life also receive THA.4 Questions arise regarding the indications for this type of replacement given that THA renders better health-related quality of life but with greater surgical morbidity and higher cost.6,7 Carroll et al.8 carried out a systematic review concluding that THA seems more cost-effective than HA. Nonetheless, they suggest the need for a cost-effectiveness analysis stratified as a function of various different clinical profiles.

As delivery of care should differ based on patients’ characteristics, the hypothesis was that the evaluation of resources used for hip replacement and their correspondence with patients’ needs would contribute to a better decision-making in the Basque Health Service. Moreover, the economic evaluation of hip replacement based on real-world data would allow to cover the gap of studies seeking to evaluate the efficiency of orthopaedic treatments using recommended methodologies.9 The objective of the study was to carry out a stratified cost-utility analysis as a function of the clinical subtypes of patients who underwent THA versus HA for the treatment of femoral neck fractures.

MethodThe clinical trial continues to be considered the research design providing the highest level of evidence. However, there are few economic studies of THA using individual patient data from randomised clinical trials and observational studies.10,11 Instead, the development of electronic health records has facilitated the creation of databases of clinical data linked to administrative data, enabling the recording of all patients’ interactions with the health system and the use of resources by individual patients (at different levels: primary care, emergency department, inpatient care, home care and outpatient specialist care).11 Such databases allow for the analysis of large samples of cases from clinical practice as a function of surgical procedure.9,11 But the analysis of samples of cases from clinical practice requires the use of procedures that improve the validity of the results, particularly regarding selection bias.12

DesignThe cost-utility study design was observational, based on statistical analysis using regression models like those employed in clinical trials with patient-level data.10 The study was conducted from Spanish National Health System perspective, implying that the costs included are those associated with hospital care.

All cases of femoral neck fracture treated by HA or THA between 2010 and 2016 in the Basque Health Service were analysed. Cases were identified considering International Classification of Disease 9th edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) code 820** for the diagnosis of femoral neck fracture and ICD-9-CM code 81.51 and 81.52 for THA and HA, respectively. Patients were followed up until 31 December 2018, ensuring a follow-up period of at least 2 years in all cases.13

Study variablesThe clinical research ethics committee of the Basque Country approved the study on 14 February 2019 (reference number PI2019010). Data were collected from the corporative database, which contains administrative and clinical records of the Basque Health Service in an anonymized form,13 including the variables: age, sex, socioeconomic status, hospital size, diagnoses required for calculating the Charlson comorbidity index,14 American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, history of antithrombotic drug use, type of anaesthesia, type of prosthesis, time to surgery in days, surgical time in minutes, hospital stay, complications up to 1 year after surgery (pulmonary thromboembolism, deep vein thrombosis, heart failure and/or pneumonia), life-long complications after surgery (loosening, luxation, fracture and/or infection of the prosthesis), date of death and place of residence. Regarding antithrombotic drugs, patients’ prescription history was searched from before hospitalisation for the following Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) codes: B01AA (vitamin K antagonists), B01AB (heparin and derivatives) and B01AC (platelet aggregation inhibitors). The costs of the prosthesis, 1minute of operating room time for the trauma unit, the hospital stay, and complications by diagnosis-related group point were obtained from the accounting system of the Basque Health Service in euros for 2018. To estimate utility, data from the scientific literature15 was used, based on the generic questionnaire EQ-5D.16 Quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) were then obtained for each patient by multiplying the years of life by the utility score for the period.17 For patients who died during the follow-up, the date of death determined the duration of follow-up, and they were assigned a utility score of 0 at that point.10 Data on unit costs and quality of life are shown in Table I of the online Appendix.

Cost-effectivenessThe efficiency of THA compared to HA was assessed by calculating the incremental cost-utility ratio (ICUR), that is, the incremental cost in euros divided by the incremental effectiveness measured in QALYs.13,17 Given that studies in the literature have not found clinical differences between THA and HA,6 the same utilities were used for both cases and obtained from a previous Spanish study.15 Individual treatment costs for each patient were calculated by adding the costs of the resources used, namely, the costs of the prosthesis, the operating room, hospitalisation, and 1-year and life-long complications. For each resource, costs were calculated by multiplying the rate of use by the unit cost, and unit costs were provided by the Basque Health Service accounting department. Given that in the scientific literature, HA is associated with less operating room time and a shorter hospital ward stay, the costs of hospitalisation for surgery were broken down into operating room costs and costs associated with hospital ward stay.18 The costs of complications during this hospitalisation were assigned based on the extent of any increase in the surgical time and/or hospital ward stay.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out using R (version 3.3.2) and Stata (version 13) statistical programmes. A variant of the propensity score based on the genetic matching algorithm was applied to balance the populations such that the characteristics of the two groups did not differ significantly at baseline.19 This technique involves selecting individuals from each of the groups with the same characteristics as a function of the chosen variables with the goal of comparing homogenous groups and thereby reducing selection bias.20 The following variables were balanced at baseline: age, sex, socioeconomic status and ASA class. A cost-utility analysis was carried out before and after applying the propensity score, taking into account the effect of ASA class and age.

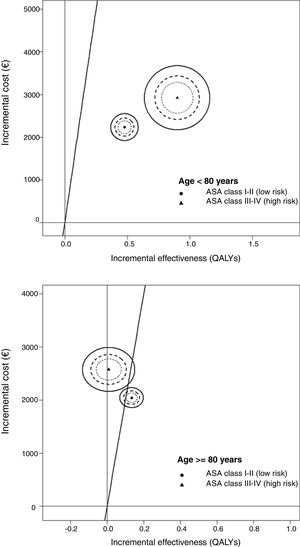

Once the sample groups had been balanced, a combined multivariate analysis for total cost and QALYs was carried out using seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) models.10 The following variables were used as covariates: procedure, sex, age, socioeconomic status, hospital size, history of antithrombotic drug use, type of anaesthesia, Charlson index, ASA class and time to surgery. Initially, a model was built without interactions, and the ICUR was calculated as the ratio of the coefficients of the procedure variables in the cost and effectiveness regressions (incremental cost as the numerator and incremental effectiveness as the denominator).10 This ICUR describes the additional costs for each additional QALY adjusted for the factors included in the cost and effectiveness models of the intervention. Subsequently, a subgroup analysis was carried out combining ASA class with age. Further, the SUR analysis assessed the uncertainty in the ICUR using the cost-effectiveness plane and the confidence ellipse, as it includes the correlation between the parameters of the two regressions (costs and QALYs) in the analysis using the variance-covariance matrix.21 The cost-effectiveness plane is a scatter plot in which the vertical axis represents the incremental costs and the horizontal axis the incremental effectiveness. In this plane, the ICUR is the slope of a line that joins any point to the origin.17 The results of the regressions draw an ellipse of points in the plane establishing the confidence intervals. When the ellipse crosses the axes, it means that the differences are not statistically significant, as the confidence interval includes zero for the incremental cost or effectiveness.

ResultsThe study identified 5867 patients diagnosed with femoral neck fractures, of whom 1307 and 4560 were treated with THA and HA, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the mean age of patients treated was 75.41 years for THA and 84.79 years for HA. Notably, 49% of patients below 80 years of age underwent THA and 51% HA. In contrast, only 12% of those ≥80 years old underwent THA. The univariate analysis did not show significant differences by sex or socioeconomic status between the two groups. Instead, significant differences were detected in ASA class, Charlson index, and age, the HA group patients having a higher Charlson index (mean 2.59 vs 1.97), as well as higher ASA class and age than those in the THA group. There were also significant differences in mortality, the rate being higher in the HA group (66.7% vs 35.8% in the THA group), despite the longer follow-up of patients who underwent THA (4.12 years vs 3.02 years in the HA group).

Univariate statistical analysis of the baseline characteristics of patients with total and partial hip replacement surgery.

| Total | Total hip arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | pa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| Patients | 5,867 | 1,307 | 4,560 | |||||

| Age (years) | Mean (SD) | 82.70 (8.97) | 75.41 (11.19) | 84.79 (6.94) | 0.000 | |||

| <80 years | 1,618 | 27.6% | 798 | 61.1% | 820 | 18.0% | 0.000 | |

| ≥80 years | 4,249 | 72.4% | 509 | 38.9% | 3,740 | 82.0% | ||

| Sex | Female | 4,340 | 74.0% | 947 | 72.5% | 3,393 | 74.4% | 0.163 |

| Male | 1,527 | 26.0% | 360 | 27.5% | 1,167 | 25.6% | ||

| Socioeconomic status | Low-intermediate (1-3) | 3,643 | 62.1% | 796 | 60.9% | 2,847 | 62.4% | 0.316 |

| (deprivation index) | High (4-5) | 2,224 | 37.9% | 511 | 39.1% | 1,713 | 37.6% | |

| Hospital type | Small (<200 beds) | 1,190 | 20.3% | 413 | 31.6% | 777 | 17.0% | 0.000 |

| Large (≥200 beds) | 4,677 | 79.7% | 894 | 68.4% | 3,783 | 83.0% | ||

| Anticoagulant/ | No | 3,890 | 66.3% | 982 | 75.1% | 2,908 | 63.8% | 0.000 |

| antiplatelet drugs | Yes | 1,977 | 33.7% | 325 | 24.9% | 1,652 | 36.2% | |

| Type of anaesthesia | Local or regional | 4,955 | 84.5% | 1,073 | 82.1% | 3,882 | 85.1% | 0.008 |

| General | 912 | 15.5% | 234 | 17.9% | 678 | 14.9% | ||

| ASA class | I-II | 3,094 | 52.7% | 798 | 61.1% | 2,296 | 50.4% | 0.000 |

| III-IV | 2,773 | 47.3% | 509 | 38.9% | 2,264 | 49.6% | ||

| Age-ASA class groups | Age: <80, ASA: I-II | 956 | 16.3% | 526 | 40.2% | 430 | 9.4% | 0.000 |

| Age: <80, ASA: III- IV | 662 | 11.3% | 272 | 20.8% | 390 | 8.6% | ||

| Age: ≥80, ASA: I-II | 2,138 | 36.4% | 272 | 20.8% | 1,866 | 40.9% | ||

| Age: ≥80, ASA: III- IV | 2,111 | 36.0% | 237 | 18.1% | 1,874 | 41.1% | ||

| Charlson index | Mean (SD) | 2.45 (2.44) | 1.97 (2.36) | 2.59 (2.44) | 0.000 | |||

| No comorbidities | 2,565 | 43.7% | 729 | 55.8% | 1,836 | 40.3% | 0.000 | |

| With comorbidities | 3,302 | 56.3% | 578 | 44.2% | 2,724 | 59.7% | ||

| 1-year complicationsb | No | 5,574 | 95.0% | 1,274 | 97.5% | 4,300 | 94.3% | 0.000 |

| Yes | 293 | 5.0% | 33 | 2.5% | 260 | 5.7% | ||

| Life-long complicationsc | No | 5,683 | 96.9% | 1,237 | 94.6% | 4,446 | 97.5% | 0.000 |

| Yes | 184 | 3.1% | 70 | 5.4% | 114 | 2.5% | ||

| Institutionalised | No | 4,695 | 80.0% | 1,135 | 86.8% | 3,560 | 78.1% | 0.000 |

| Yes | 1,172 | 20.0% | 172 | 13.2% | 1,000 | 21.9% | ||

| Death at final follow-up | No | 2,358 | 40.2% | 839 | 64.2% | 1,519 | 33.3% | 0.000 |

| Yes | 3,509 | 59.8% | 468 | 35.8% | 3,041 | 66.7% | ||

| Time to surgery (days) | Mean (SD) | 2.82 (2.77) | 2.71 (2.96) | 2.85 (2.72) | 0.120 | |||

| Follow-up (years) | Mean (SD) | 3.26 (2.34) | 4.10 (2.35) | 3.02 (2.28) | 0.000 | |||

| QALYs | Mean (SD) | 2.38 (2.33) | 2.99 (1.72) | 2.20 (1.66) | 0.000 | |||

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; QALYs: quality-adjusted life years; SD: standard deviation.

During follow-up, the percentage of patients with any type of complication during the first year after surgery was lower in the THA group than in the HA group, while the percentage of patients with some long-life complication was higher. Table 2 indicates that the costs were significantly higher for patients who underwent THA than for those who underwent HA.

Univariate statistical analysis of the cost for patients undergoing total and partial hip arthroplasty using the unit costs from 2018 in euros.

| Total | Total hip arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 5,867 | 1,307 | 4,560 | |

| Costs of implant | 1,218 | 2,509 | 848 | 0.000 |

| Costs of operating room | 2,940 | 3,202 | 2,865 | 0.000 |

| Costs of hospital stay | 7,279 | 7,462 | 7,227 | 0.180 |

| Costs of complications | 443 | 531 | 418 | 0.927 |

| Total costs | 11,880 | 13,704 | 11,357 | 0.000 |

Table 3 shows the cost-utility analysis carried out before and after genetic matching. In both cases, THA is more costly and more effective than HA, with incremental differences after balancing the groups of €1825 and 0.55 QALYs. In the analysis by ASA class and age subgroups, the same results for ASA class I and II patients were found. In contrast, HA was dominant for patients aged ≥80 years old and classified as ASA class III or IV.

Cost-utility analysis of total vs partial hip arthroplasty surgery before and after genetic matching.

| Before genetic matching | Total hip arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | Δ Cost | Δ QALYs | ICUR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (mean) | QALYs (mean) | Cost (mean) | QALYs (mean) | ||||

| Total | 13,704 | 3.01 | 11,357 | 2.20 | 2,346 | 0.81 | 2,912 |

| Age <80 years | |||||||

| ASA class I-II | 13,327 | 3.56 | 12,436 | 2.91 | 891 | 0.65 | 1,361 |

| ASA class III-IV | 15,241 | 3.20 | 11,907 | 2.35 | 3,334 | 0.85 | 3,902 |

| Age ≥80 years | |||||||

| ASA class I-II | 12,542 | 2.62 | 11,152 | 2.33 | 1,390 | 0.29 | 4,756 |

| ASA class III-IV | 14,107 | 1.99 | 11,200 | 1.88 | 2,908 | 0.11 | 26,689 |

| After genetic matching | Total hip arthroplasty | Hemiarthroplasty | Δ Cost | Δ QALYs | ICUR | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost (mean) | QALYs (mean) | Cost (mean) | QALYs (mean) | ||||

| Total | 13,704 | 3.01 | 11,878 | 2.46 | 1,825 | 0.55 | 3,310 |

| Age <80 years | |||||||

| ASA class I-II | 13,327 | 3.56 | 12,258 | 2.84 | 1,069 | 0.72 | 1,483 |

| ASA class III-IV | 15,241 | 3.20 | 12,577 | 2.16 | 2,665 | 1.05 | 2,550 |

| Age ≥80 years | |||||||

| ASA class I-II | 12,542 | 2.62 | 11,084 | 2.43 | 1,458 | 0.19 | 7,634 |

| ASA class III-IV | 14,107 | 1.99 | 11,128 | 2.01 | 2,980 | -0.01 | Dominated |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; ICUR: incremental cost-utility ratio; QALYs: quality-adjusted life years.

Table 4 summarises the results of the multivariate SUR model for the incremental cost and effectiveness without any type of interaction. These results are in line with those of the univariate analysis, indicating that THA was more costly and more effective than HA, with an incremental cost of €2465 and an incremental effectiveness of 0.42 QALYs. The analysis of the subgroups derived from the interaction between ASA class and age in the SUR model (Table 5 and Fig. 1) revealed that THA was not cost effective in ASA class III-IV patients aged ≥ 80 years old. It should be noted that Tables 4 and 5 show the results of the SUR models in a summarised way. Nevertheless, the complete SUR models results are available in Tables II-IV of the online Appendix.

Seemingly unrelated regression models for incremental cost (euros) and effectiveness (quality-adjusted life years) without any interaction.

| Costa | QALYsa | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to surgery (days) | 893 (879 - 907)b | −0.03 (−0.03 - −0.02)b |

| Age: ≥ 80 years | −418 (-521 - −315)b | −0.60 (−0.63 - −0.56)b |

| Sex: male | 243 (133 - 353)b | −0.33 (−0.37 - −0.29)b |

| Socioeconomic status: low | 62 (−38 - 161) | 0.10 (0.06 - 0.13)b |

| Hospital type: large (≥200 beds) | 215 (94 - 337)b | 0.12 (0.08 - 0.16)b |

| Anticoagulant/antiplatelet drug use: yes | −240 (−355 - −125)b | −0.56 (−0.60 - −0.52)b |

| Type of anaesthesia: general | 899 (768 - 1029)b | 0.12 (0.08 - 0.17)b |

| Charlson index: with comorbidity | 955 (852 - 1058)b | −0.78 (−0.81 - −0.74)b |

| ASA class: III-IV (high risk) | 582 (480 - 683)b | −0.31 (−0.35 - −0.28)b |

| Procedure: total hip arthroplasty | 2465 (2365 - 2565)b | 0.42 (0.38 - 0.45)b |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; QALYs: quality-adjusted life years.

Effects of total hip arthroplasty in the incremental cost (euros) and effectiveness (quality-adjusted life years) calculated using seemingly unrelated regression models as a function of the interaction between age and ASA class.

| Costa | QALYsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age: <80 years | Age: ≥80 years | Age: <80 years | Age: ≥80 years | |

| ASA class: I-II (low risk) | 2,236 (1,984 - 2,488)b | 2,045 (1,895 - 2,194)b | 0.48 (0.39 - 0.57)b | 0.13 (0.08 - 0.19)b |

| ASA class: III-IV (high risk) | 2,925 (2,257 - 3,593)b | 2,576 (2,213 - 2,938)b | 0.90 (0.66 - 1.13)b | 0.01 (−0.12 - 0.13)b |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; QALYs: quality-adjusted life years.

The main contribution of this economic assessment is to provide evidence that it is more efficient to perform HA in most patients with displaced femoral neck fracture and reserve THA for the youngest patients and those classified as low risk.22 This analysis has been possible thanks to the disaggregation of cost-effectiveness by subgroups as a function of age and ASA class. To restrict the economic assessment to the entire sample would have led to a misleading result, since it would not have addressed the clinical heterogeneity of patients. Further, the importance of adjusting the results is even more evident if the high cost of the surgical procedures studied is considered and that the already elevated incidence of femoral fractures is expected to grow in the future due to population ageing.23 It is also noteworthy that this is the first cost-utility analysis using individual clinical information extracted from corporate databases (real-world data) in Spain.11

The unstratified results indicated that THA was more expensive and associated with more QALYs than HA and that the ICUR was lower than the €22,000 per QALY willingness-to-pay threshold or cut-off value.24 Although the incremental cost and effectiveness were lower once the groups were balanced, the ICUR remained practically stable, only changing from €2912 per QALY to €3310 per QALY. When the SUR model was used to adjust the incremental cost-effectiveness as a function of the different variables, the results were similar, THA being more expensive and more effective than HA, with an ICUR of €5869 per QALY. On the other hand, when the interaction between ASA class and age was included, this conclusion only held for the subgroups of patients under 80 years of age. In these patients, THA was cost-effective, with both the ICUR and the confidence intervals below the cut-off value and not crossing the axes of the cost-effectiveness plane. In contrast, the results in the subgroups of patients ≥ 80 years old are harder to interpret. THA was not cost-effective in the low risk (ASA class I-II) group, the confidence intervals being above the cut-off, and was dominated by HA in the high risk (ASA class III-IV) group. As can be observed in the cost-effectiveness plane, in this subgroup, the two surgical procedures have the same effectiveness but THA has an incremental cost of €2576. In economic assessments, an intervention is considered dominated when it has a lower utility for the patient at a higher cost.17

The results of the economic evaluation fit well with the distribution of replacement type in the subsample of patients above 80 years old, only 12% of these patients undergoing THA. On the other hand, they may seem inconsistent with the distribution in under-80-year-olds, THA being the procedure of choice in 49% of cases. It is plausible that surgeon experience at the local level to carry out a more complex procedure such as THA helps to explain these differences.8 It has been reported that HA procedures are performed by a wide range of surgeons, while THA procedures in fractures tend to be carried out by fewer surgeons, with considerable experience.8 The results are in line with this. Specifically, when analysing the differences in the distribution of the replacement type as a function of hospital size, it was found that the procedures corresponded to THA in 17% of cases in large hospitals and 32% of cases in small hospitals. It is likely that one of the reasons for this difference is that patients with more comorbidities are referred to large hospitals.4

The results of studies reported in the literature are similar to ours, although they have not estimated cost-effectiveness as a function of clinical subgroup.8,25 Based on Markov models, Slover et al.25 calculated that the ICUR of THA vs HA was $1960 per QALY in the USA. They based themselves on a previous study by Keating et al.26 that indicated a better quality of life after 24 months in patients who underwent THA. The same data were used in another Markov model in the context of a systematic review to estimate an ICUR of £7952 per QALY in the United Kingdom.8 On the other hand, the improvement described by Keating et al. has not been confirmed in other studies;6 hence, in our study, the same utilities were assumed in both options.15 In the aforementioned studies, the great difference in utility scores is a key factor in the ICUR for THA being below the €22,000 per QALY cut-off, and hence, this intervention being considered cost-effective.26,27 Notably, in another study that assessed the long-term functional capacity of patients who underwent one of these two surgical interventions,28 there were no differences in the results at 12 years after surgery. Nonetheless, this study has been criticized for the methodology used to assess the functional status of patients, the lack of assessment before surgery and the fact that less than a quarter of the patients in both groups were alive at the end of the follow-up period.29

The observational design used in the study does not have the internal validity of clinical trials.11 Patient recruitment from databases that are representative of clinical practice can be seen as a limitation, given that the decision regarding type of surgery has been based on the judgement of different orthopaedic surgeons. On the other hand, seeking to support surgical decision making, observational studies that analyse real-world data are increasingly common, given their high external validity.18,30 The current availability of information from electronic medical records presents an ideal opportunity for measuring the real effectiveness and cost of different treatments. Nonetheless, given the non-random design of the study, the clinical characteristics of the two groups differ due to the selection bias. To overcome this, the recommendations of expert groups were followed regarding the use of real-world data in economic assessments.11 This approach includes propensity score analysis to ensure that the observed baseline distribution of the covariates is similar in both groups. In our case, the potential bias was addressed using a genetic matching algorithm.19 Now that the electronic health records and administrative registries facilitate access to real data from health systems, it is essential to develop and apply procedures that overcome their weaknesses and improve the validity of results obtained from their analysis.12

The main limitation of the study is the lack of information regarding utilities at the patient level. Given that the Basque Health Service does not systematically record utility scores for patients with hip prostheses, the data concerning utilities used for the calculation of QALYs was taken from a study that measured the quality of life of patients with hip prostheses.15 The same values were used in both groups of surgical patients, given that an international randomised controlled trial did not identify any significant difference in clinical improvement between THA and HA.6 In the future, the systematic recording of patient-reported outcome measures in clinical databases will allow us to standardise the use of economic assessments with data from clinical practice and enable decisions to be informed by specific data from each healthcare system.

The conclusion of this cost-utility study is that subgroup analysis supports current daily clinical practice in displaced femoral neck fractures, namely, using partial hip replacement in most patients and reserving total hip replacement for younger patients. Further, this study opens the use of real-world data for the economic evaluation of surgical procedures.

Displaced femoral neck fractures usually require hip replacement. Most commonly partial hip replacement or hip hemiarthroplasty is the chosen one because it is less aggressive, achieves similar health-related quality of life results and is less expensive than total hip arthroplasty. Total hip arthroplasty tends to be indicated for younger patients who have a better quality of life and longer life expectancy. Nonetheless, patients of advanced age also receive total hip arthroplasty, so questions arise regarding the indications for this type of replacement.

What does this study add to the literature?The study adds to the literature a stratified cost-utility analysis of total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty as a function of clinical subtype. It is based in real world data and conducted taking into account all the replacements done between 2010 and 2016 in the Basque Health Service for the displaced femoral neck fractures.

What are the implications of the results?The study has implications for the practice because it supports the current daily clinical practice in displaced femoral neck fractures. The study validates the use of partial replacement in most patients and the reservation of total replacement for younger patients.

David Cantarero.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsI. Larrañaga and I. Etxebarria-Foronda conceived and designed the research. I. Etxebarria-Foronda, O. Ibarrondo and J.M. Martínez-Llorente obtained the data, and interpreted the data. I. Larrañaga, A. Gorostiza and C. Ojeda-Thies designed the methods, performed the analyses and interpreted the data. I. Larrañaga drafted the manuscript and approved the final manuscript. I. Etxebarria-Foronda critically revised the manuscript. I. Etxebarria-Foronda, O. Ibarrondo, A. Gorostiza, C. Ojeda-Thies and J.M. Martínez-Llorente revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge the help of Ideas Need Communicating Language Services in improving the use of English in the manuscript.

FundingThe study was funded by the Basque Government Department of Health (grant number 2020111021). The funding source had no involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report and in the decision to submit the article.

Conflicts of interestNone.