To describe the maternal, neonatal and pregnancy characteristics related to inhibition of lactation (IL) with cabergoline.

MethodWe assessed 20,965 occasions of breastfeeding initiation, according to data collected from obstetric records at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona (Spain) between January 2011 and December 2017.

ResultsIL decreased over the study period from 8.78% to 6.18% (odds ratio [OR]: 0.93 per year; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 0.90-0.95). Women with a lower educational level (OR: 2.5; 95%CI: 2.0-3.0), mothers living in more depressed areas (OR: 1.08 per 10 extra points over 100; 95%CI: 1.04-1.12), smokers (OR: 2.2; 95%CI: 1.9-2.6), and those with more children (OR: 1.2 for each sibling; 95%CI: 1.1-1.3), preterm birth (OR: 1.8; 95%CI: 1.4-2.3), multiple births (OR: 1.6; 95%CI: 1.2-2.1) and a higher risk pregnancy (OR: 1.3 per risk point; 95%CI: 1.2-1.4) showed a higher prevalence of IL. Compared to women born in Spain, IL was less likely in all other women with the exception of Chinese women (OR: 7.0; 95%CI: 5.7-8.6). These disparities remained during the study period.

ConclusionsFactors related to lower socioeconomic status and poor health were more likely to be associated with IL. The overall use of cabergoline decreased during the study period while inequalities persisted. Taking these inequalities into account is the first step to addressing them.

Describir las características maternas, neonatales y del embarazo relacionadas con la inhibición de la lactancia (IL) con cabergolina.

MétodoSe evaluaron 20.965 ocasiones de inicio de lactancia, según los registros obstétricos del Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (2011-2017).

ResultadosLa IL disminuyó durante el periodo de estudio del 8,78% al 6,18% (odds ratio [OR]: 0,93 anual; intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%]: 0,90-0,95). Las mujeres con menor nivel educativo (OR: 2,5; IC95%: 2,0-3,0), las madres que viven en áreas más deprivadas (OR: 1,08 por 10 puntos extra sobre 100; IC95%: 1,04-1,12), las fumadoras (OR: 2,2; IC95%: 1,9-2,6), las que tienen más hijos (OR: 1,2 por cada hermano; IC95%: 1,1-1,3), los nacimientos prematuros (OR: 1,8; IC95%: 1,4-2,3), los nacimientos múltiples (OR: 1,6; IC95%: 1,2-2,1) y los embarazos de mayor riesgo (OR: 1,3 por punto de riesgo; IC95%: 1,2-1,4) tuvieron una mayor prevalencia de IL. Respecto a las mujeres nacidas en España, la IL fue menor que en las demás mujeres, con la excepción de las nacidas en China (OR: 7,0; IC95%: 5,7-8,6). Estas desigualdades se mantuvieron durante el periodo de estudio.

ConclusionesLos factores relacionados con el bajo nivel socioeconómico y la mala salud tuvieron más probabilidades de estar asociados con la IL. El uso de cabergolina disminuyó durante el periodo de estudio, mientras que las desigualdades se mantuvieron. Tener en cuenta estas desigualdades es el primer paso para abordarlas.

The beneficial health effects of breastfeeding for infants and mothers have been well-established and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that infants be exclusively breastfed for the first 6 months of life and be continued for a minimum of 2 years.1 Differences in breastfeeding are part of the health inequalities beginning in childhood.2 A number of studies have described different prevalence of breastfeeding initiation (BI) in terms of maternal, newborn and hospital characteristics.3 For example, it has been described that the prevalence of breastfeeding initiation is higher in older working women with a higher socioeconomic level.4–9 Several studies have reported that maternal origin also plays a role in BI.10–12 The prevalence of breastfeeding depends on hospital practices13 and is higher in mothers expressing prenatal and pre-pregnancy intention of breastfeeding14 and in those with a higher perception of self-efficacy.15 The inequalities of BI have been evaluated in high-income countries such as Ireland,5 the Netherlands,9 Croatia,16 Canada,4 Scotland,8 Australia,17 the United States of America6,7 and the United Kingdom.18 The WHO recommends the evaluation of these inequalities and studies on their trends over time,19 considering the impact breastfeeding has on the health of mothers and infants along their lives.2

According to the 2015 Health Survey, in Catalonia, 84.8% of newborns were breastfed at birth20 with some inequalities having been described in Spain.21–23 Nonetheless, some mothers wish not to breastfeed or breastfeeding may be contraindicated for medical reasons.24 In these cases, pharmacological inhibition of lactation (IL) with cabergoline is the most common practice.25 To our knowledge, there are no studies describing the characteristics associated with cabergoline prescription for IL. Therefore, the present study describes the maternal, neonatal and pregnancy characteristics related to IL with cabergoline at birth.

MethodWe conducted a retrospective cohort study of women, followed during pregnancy, with obstetric clinic history records who had delivered at least one live infant at the Hospital Clínic de Barcelona (HCB), a large university referral hospital, between January 2011 and December 2017. Singleton stillbirth and pregnancy interruptions were excluded. IL was defined as the administration of 1mg of carbegoline while hospitalised during the postpartum period.25

Maternal variables (age, country of origin, parity, educational level, professional status, tobacco, alcohol or other drug use during pregnancy, antenatal intention of natural birth, area of residence, pregnancy variables [gestation risk level according to local guidelines,24 0: low, 1: intermediate, 2: high, 3: very high], multiple gestation, year of delivery, gestational age at delivery, type of delivery) and newborn characteristics (sex, use of reanimation procedures) were obtained through the medical records of the Maternal-Fetal Medicine Department during pregnancy, delivery and postpartum hospitalisation. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status and drug use that required IL were considered medical contraindications to breastfeed. The area of residence was used to determine if the case belonged to the area of reference of the hospital or was referred to for high complexity. Each woman was assigned the socioeconomic index of their area of residence from the Catalonian Health System,26 which reflects socioeconomic differences using a formula including occupation, social class, education, living conditions, income, social cohesion, among others. This indicator provides a score ranging from 0-100 indicating low to high deprivation.26 Cabergoline use and date of administration were obtained from the hospital pharmacy records. Cabergoline use postpartum was established as the main endpoint.

Absolute frequencies and percentages were used to describe categorical variables and means and standard deviation or 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) to describe quantitative variables with a normal distribution, and medians and interquartile range otherwise. Bivariate analysis was made using cabergoline administration for IL (yes/no) as the response variable in a logistic regression model. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was carried out including significant variables in the bivariate analysis and those considered relevant due to their clinical interest. Disaggregated analysis per year of delivery was performed. The odds ratio (OR) and 95%CI were calculated and statistical significance was established as p <0.05. The analysis was performed using the R statistical software, version 3.5.

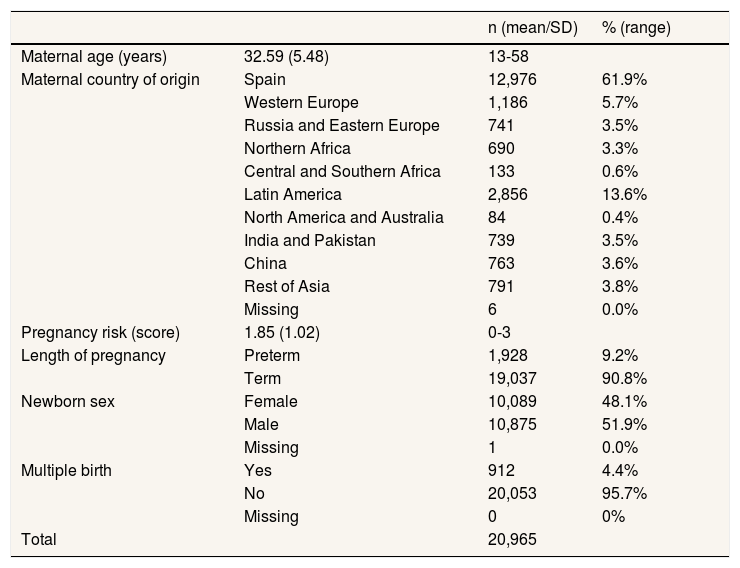

ResultsOf the 20,965 occasions for BI, 6.86% women received cabergoline to suppress breastfeeding. The main maternal, neonatal and pregnancy characteristics are described in Table 1.

The main maternal, neonatal and pregnancy characteristics.

| n (mean/SD) | % (range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 32.59 (5.48) | 13-58 | ||

| Maternal country of origin | Spain | 12,976 | 61.9% | |

| Western Europe | 1,186 | 5.7% | ||

| Russia and Eastern Europe | 741 | 3.5% | ||

| Northern Africa | 690 | 3.3% | ||

| Central and Southern Africa | 133 | 0.6% | ||

| Latin America | 2,856 | 13.6% | ||

| North America and Australia | 84 | 0.4% | ||

| India and Pakistan | 739 | 3.5% | ||

| China | 763 | 3.6% | ||

| Rest of Asia | 791 | 3.8% | ||

| Missing | 6 | 0.0% | ||

| Pregnancy risk (score) | 1.85 (1.02) | 0-3 | ||

| Length of pregnancy | Preterm | 1,928 | 9.2% | |

| Term | 19,037 | 90.8% | ||

| Newborn sex | Female | 10,089 | 48.1% | |

| Male | 10,875 | 51.9% | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0.0% | ||

| Multiple birth | Yes | 912 | 4.4% | |

| No | 20,053 | 95.7% | ||

| Missing | 0 | 0% | ||

| Total | 20,965 |

SD: standard deviation.

The HCB attends inhabitants from the city of Barcelona (67%) and is a reference center for more complex cases from the rest of Catalonia and Spain (43%). The population included 90 (0.4%) HIV positive women and 118 (0.5%) drug users in whom breastfeeding was contraindicated. Three women (0.1%) satisfied both conditions. The proportion of these groups in 2011 and 2017 did not differ significantly. The overall prevalence of cabergoline use decreased from 8.78% to 6.18% (OR: 0.93 per year; 95%CI: 0.90-0.95) during the study period.

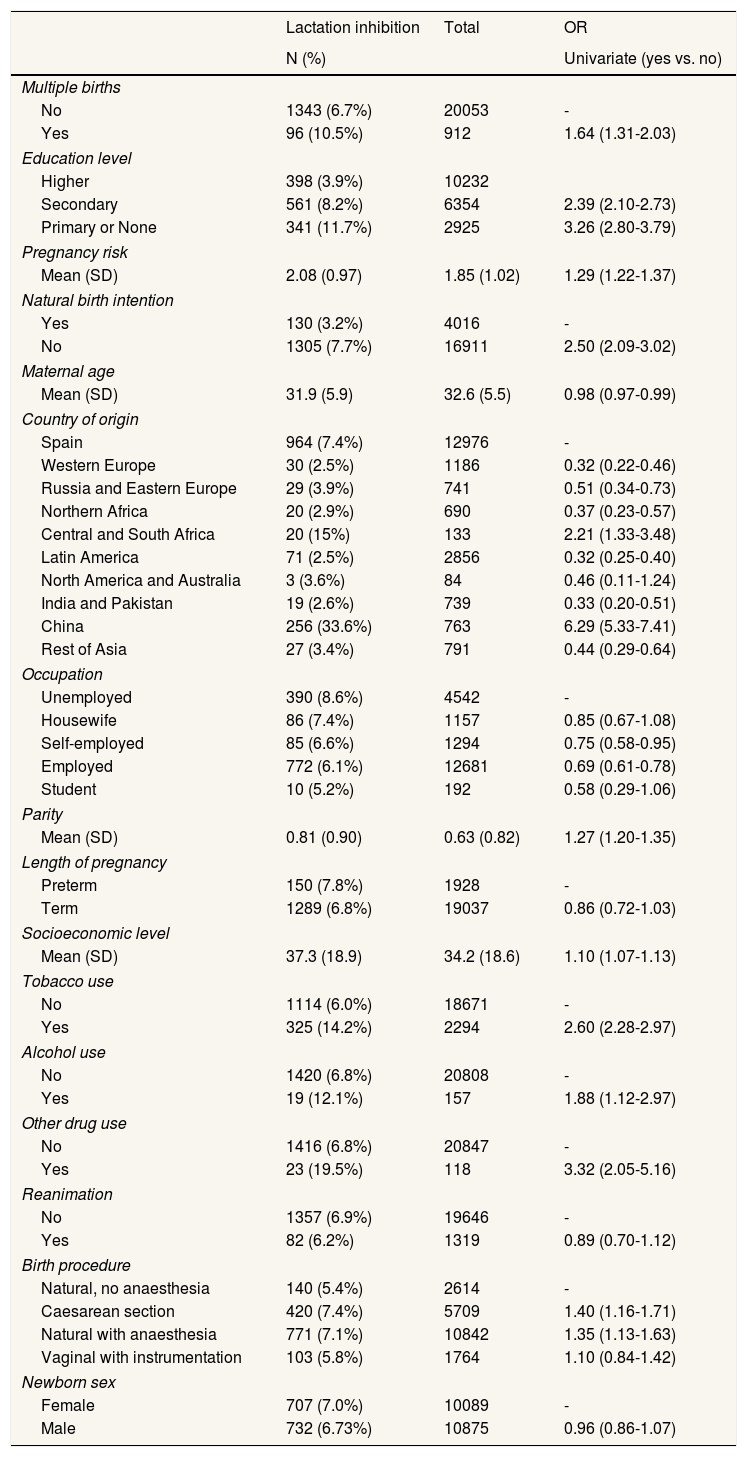

Several variables showed significant association with IL in the bivariate analysis (Table 2). Disaggregated data analysis per year of delivery showed no significant changes in the other variables.

Bivariate analysis of lactation inhibition at the Hospital Clinic of Barcelona from 2011 to 2017.

| Lactation inhibition | Total | OR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | Univariate (yes vs. no) | ||

| Multiple births | |||

| No | 1343 (6.7%) | 20053 | - |

| Yes | 96 (10.5%) | 912 | 1.64 (1.31-2.03) |

| Education level | |||

| Higher | 398 (3.9%) | 10232 | |

| Secondary | 561 (8.2%) | 6354 | 2.39 (2.10-2.73) |

| Primary or None | 341 (11.7%) | 2925 | 3.26 (2.80-3.79) |

| Pregnancy risk | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.08 (0.97) | 1.85 (1.02) | 1.29 (1.22-1.37) |

| Natural birth intention | |||

| Yes | 130 (3.2%) | 4016 | - |

| No | 1305 (7.7%) | 16911 | 2.50 (2.09-3.02) |

| Maternal age | |||

| Mean (SD) | 31.9 (5.9) | 32.6 (5.5) | 0.98 (0.97-0.99) |

| Country of origin | |||

| Spain | 964 (7.4%) | 12976 | - |

| Western Europe | 30 (2.5%) | 1186 | 0.32 (0.22-0.46) |

| Russia and Eastern Europe | 29 (3.9%) | 741 | 0.51 (0.34-0.73) |

| Northern Africa | 20 (2.9%) | 690 | 0.37 (0.23-0.57) |

| Central and South Africa | 20 (15%) | 133 | 2.21 (1.33-3.48) |

| Latin America | 71 (2.5%) | 2856 | 0.32 (0.25-0.40) |

| North America and Australia | 3 (3.6%) | 84 | 0.46 (0.11-1.24) |

| India and Pakistan | 19 (2.6%) | 739 | 0.33 (0.20-0.51) |

| China | 256 (33.6%) | 763 | 6.29 (5.33-7.41) |

| Rest of Asia | 27 (3.4%) | 791 | 0.44 (0.29-0.64) |

| Occupation | |||

| Unemployed | 390 (8.6%) | 4542 | - |

| Housewife | 86 (7.4%) | 1157 | 0.85 (0.67-1.08) |

| Self-employed | 85 (6.6%) | 1294 | 0.75 (0.58-0.95) |

| Employed | 772 (6.1%) | 12681 | 0.69 (0.61-0.78) |

| Student | 10 (5.2%) | 192 | 0.58 (0.29-1.06) |

| Parity | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.81 (0.90) | 0.63 (0.82) | 1.27 (1.20-1.35) |

| Length of pregnancy | |||

| Preterm | 150 (7.8%) | 1928 | - |

| Term | 1289 (6.8%) | 19037 | 0.86 (0.72-1.03) |

| Socioeconomic level | |||

| Mean (SD) | 37.3 (18.9) | 34.2 (18.6) | 1.10 (1.07-1.13) |

| Tobacco use | |||

| No | 1114 (6.0%) | 18671 | - |

| Yes | 325 (14.2%) | 2294 | 2.60 (2.28-2.97) |

| Alcohol use | |||

| No | 1420 (6.8%) | 20808 | - |

| Yes | 19 (12.1%) | 157 | 1.88 (1.12-2.97) |

| Other drug use | |||

| No | 1416 (6.8%) | 20847 | - |

| Yes | 23 (19.5%) | 118 | 3.32 (2.05-5.16) |

| Reanimation | |||

| No | 1357 (6.9%) | 19646 | - |

| Yes | 82 (6.2%) | 1319 | 0.89 (0.70-1.12) |

| Birth procedure | |||

| Natural, no anaesthesia | 140 (5.4%) | 2614 | - |

| Caesarean section | 420 (7.4%) | 5709 | 1.40 (1.16-1.71) |

| Natural with anaesthesia | 771 (7.1%) | 10842 | 1.35 (1.13-1.63) |

| Vaginal with instrumentation | 103 (5.8%) | 1764 | 1.10 (0.84-1.42) |

| Newborn sex | |||

| Female | 707 (7.0%) | 10089 | - |

| Male | 732 (6.73%) | 10875 | 0.96 (0.86-1.07) |

OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation.

Tobacco and alcohol use, and tobacco and other drug use were confounding factors in the multivariate model. Alcohol and other drug use were not considered in the final model. Age and parity, and parity and country of origin were also confounding factors. A total of 11.2% of women had more than one delivery resulting in a live infant during the study period. The variable parity was a proxy of repeated episodes, and was maintained for sensitivity analysis. After testing the correlation among age, parity and year of delivery (Spearman test parity and age p=0.09; year of delivery and age p=0.09; year of delivery and parity p=0.13), the year of delivery was excluded and shown separately. Models with and without missing values showed no differences. All the models show the analysis without missing values.

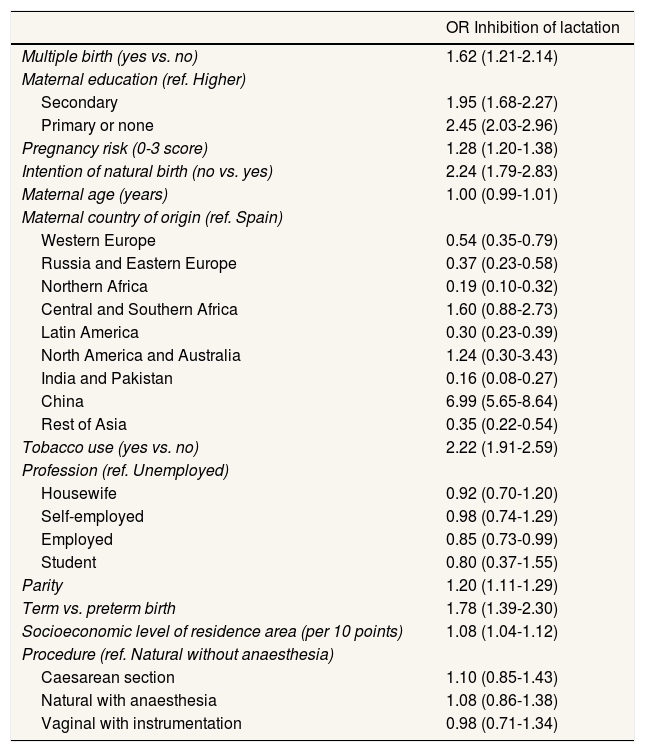

Table 3 shows a multivariate model with selected variables. IL was significantly higher in women with no education or with primary studies compared to women with a higher education and those living in more economically depressed areas. Breastfeeding was also more inhibited in women who did not wish to undergo natural birth, smokers, with previous children, at term versus preterm birth, in women with multiple births and in those with a higher risk pregnancy. Taking Spanish women as the reference, women born in Northern Africa, India and Pakistan, Russia and Eastern and Western Europe were less likely to inhibit breastfeeding. IL was significantly more likely in Chinese women. A multivariate model with disaggregated data considering the place of residence (city of Barcelona versus the rest of Catalonia) showed no differences.

Multivariate analysis of lactation inhibition at the Hospital Clínic of Barcelona from 2011 to 2017.

| OR Inhibition of lactation | |

|---|---|

| Multiple birth (yes vs. no) | 1.62 (1.21-2.14) |

| Maternal education (ref. Higher) | |

| Secondary | 1.95 (1.68-2.27) |

| Primary or none | 2.45 (2.03-2.96) |

| Pregnancy risk (0-3 score) | 1.28 (1.20-1.38) |

| Intention of natural birth (no vs. yes) | 2.24 (1.79-2.83) |

| Maternal age (years) | 1.00 (0.99-1.01) |

| Maternal country of origin (ref. Spain) | |

| Western Europe | 0.54 (0.35-0.79) |

| Russia and Eastern Europe | 0.37 (0.23-0.58) |

| Northern Africa | 0.19 (0.10-0.32) |

| Central and Southern Africa | 1.60 (0.88-2.73) |

| Latin America | 0.30 (0.23-0.39) |

| North America and Australia | 1.24 (0.30-3.43) |

| India and Pakistan | 0.16 (0.08-0.27) |

| China | 6.99 (5.65-8.64) |

| Rest of Asia | 0.35 (0.22-0.54) |

| Tobacco use (yes vs. no) | 2.22 (1.91-2.59) |

| Profession (ref. Unemployed) | |

| Housewife | 0.92 (0.70-1.20) |

| Self-employed | 0.98 (0.74-1.29) |

| Employed | 0.85 (0.73-0.99) |

| Student | 0.80 (0.37-1.55) |

| Parity | 1.20 (1.11-1.29) |

| Term vs. preterm birth | 1.78 (1.39-2.30) |

| Socioeconomic level of residence area (per 10 points) | 1.08 (1.04-1.12) |

| Procedure (ref. Natural without anaesthesia) | |

| Caesarean section | 1.10 (0.85-1.43) |

| Natural with anaesthesia | 1.08 (0.86-1.38) |

| Vaginal with instrumentation | 0.98 (0.71-1.34) |

OR: odds ratio.

To our knowledge this is the first study to describe the maternal, neonatal and pregnancy characteristics related to inequalities in pharmacological inhibition of lactation in the postpartum period. Some factors related to a lower socioeconomic status and poor health were found to be more likely associated with IL. The overall use of cabergoline decreased during the study period while inequalities remained the same. The country of birth of the mothers was also associated with the prevalence of IL.

The first step for successful breastfeeding is early initiation. Although IL and BI are not the same, they are closely related. In high-income countries, many of the factors which this study found to be associated with IL have also been reported to be associated with BI. The results of this study show a slight decrease in the IL. The overall decrease of IL is aligned with the general tendency to increase BI in Catalonia,20 which passed from 82.5% in 2011 to 87.5% in 2016. In the world, this tendency is also observed since the beginning of the 21st century.27,28 In addition, the inequalities found were similar to those reported in previous studies on BI conducted in Spain.21,23,29 The gap between IL found in our study and the BI described in the general population could be explained in part by early failure in women willing to breastfeed.

Since the medical contraindication to breastfeed is very low, we can assume that the majority of cases of IL were the result of mother's decision, but more research is needed. The persistence of inequalities has also been described in other populations,4,30,31 indicating the need to address them. No differences among the variables of the model or in the proportion of medical contraindications for lactation were detected in the study period, maybe due to the small size of the subgroups.

Similarly to our findings in LI, a lower BI is associated with women with a lower socioeconomic status,3 living in more economically depressed areas7,8,21,23 and in those with a lower level of education.8,23 Our study found IL to be higher in smokers5 and in multiple pregnancies, both being similar to what has been reported in BI,23,32 and with a higher pregnancy risk. Possible explanations for this include an increased perception of difficulty, a lower feeling of self-efficacy and less specific support for these groups. Our study also described more IL in women with a second child and following children, which could be partly explained by previously negative breastfeeding experiences, within a context in which breastfeeding is suboptimal.3,33,34

The results of previous studies are not conclusive in regard to the effect of prematurity on BI. Some authors have found a lower BI in these,11,23 while others describe no differences.35 Many premature newborns have difficulties in BI, although the maternal intention is to breastfeed and therefore do not inhibit lactation, making comparison between IL and BI difficult. Nevertheless, the HCB has a specific program for prematurity that probably explains why preterm mothers are less likely to inhibit lactation in our setting. According to one study,11 which reported differences in lactation in premature infants based on the ethnicity of the mother, different degrees of prematurity as well as interaction with different variables should be considered in IL.

When we analysed maternal age or mode of delivery independently from the rest of the variables, we observed an increase in IL in younger women and in those undergoing caesarean section, as reported by other studies on BI.5,6,11,21,23 However, we found that on adjustment for the rest of the variables, neither maternal age nor mode of delivery were significant. Similarly to the case of prematurity, this highlights the differences between BI and IL.

As described in other studies on BI,5–7 the results of our study show the lower the level of education the higher the prevalence of IL.3 Employed mothers, the study group with longest and best paid maternity leaves, were also found to be less likely to inhibit lactation. This finding supports the WHO advocacy for paid maternity leave.

The origin of the mothers has an effect on IL. Although there is no idiomatic barrier, the prevalence of IL in Spanish mothers was neither the highest nor the lowest. With the exception of Chinese women,21,23 all other origins showed a better prevalence of BI. Several studies have described these disparities in Europe and the US5–7,10–12,29 and have shown that mothers whose country of residence is different from the country of origin are more likely to initiate breastfeeding. The prevalence of IL among migrant women in our study is probably higher when the prevalence of BI in their countries of origin is lower. Taking Chinese mothers as an example, it was found27 that almost 70% of women in China initiated breastfeeding in 2014, which is the same prevalence we found for non-IL. Another study conducted in Spain22 also found Chinese mothers to be less likely to breastfeed which was attributed to the working conditions of Chinese mothers in Spain and some mothers sending their newborns to their extended families in China (12%).

Registering separately IL from BI failure and studying the reasons and motivations associated with them could shed some light on the promotion of breastfeeding and needs of support for new mothers. More support to breeding women could be offered and health care and maternal groups could be tailored to specific groups, some of them even during pregnancy (e.g., multiple gestations, high risk pregnancies, non-first child pregnancies, preterm birth). Primary care and hospital coordination in a lactation committee following the Initiative for the Humanization of Assistance to Birth and Lactation guidelines could help to improve knowledge and coordinate measures to address inequalities. Besides, medical contraindications should be prevented in advance (HIV infection and drug use prevention). Health policies should take into account that lactation is more likely to be suppressed in women who live in more deprived areas, who are not employed, have a lower level of education and are in situations with greater risk of poor health and high risk habits (higher gestational risk, multiple births, smokers), showing how health disparities can be transmitted among generations.

A limitation of this study is that socioeconomic variables were limited to the ones presented in the analysis, since they were not registered. The socioeconomic variable refers to the area of residence. The number of years of residence in Spain of migrant women was not known. Another limitation is that data included are from only one setting, a referral hospital, that receives patients from all over Catalonia. Considering this limitation, data from patients from the referral area have been analysed separately from the referred ones and no differences were found. Some variables are recorded in an incomplete way, like parity, which does not include previous experiences in lactation, and attendance to maternal education programs. Finally, one quarter of the population of Catalonia also has private medical insurance apart from the public, universal, health coverage provided. Women with a higher income may use their private insurance when delivering and this may induce an underestimation in the differences in socioeconomic variables.

One strength of this study was the inclusion of the whole population attended at the HCB over a 7-year period. Another strength is the use of the pharmacy records as the source of the data. To our knowledge this is the first study to use these records and this provides a good description of IL at birth.

ConclusionsThe IL in puerperal women is related to several factors including a lower socioeconomic status and poor health. The overall use of cabergoline decreased during the study period while inequalities among the women studied persisted. Nonetheless, taking these inequalities into account is the first step to addressing them.

Inequalities in breastfeeding initiation have an impact on the health of mothers and infants along their lives. Socioeconomic factors associated with breastfeeding initiation in high-income countries have been described.

What does this study add to the literature?This study describes disparities in inhibition of lactation by pharmacological means by showing that factors related to lower socioeconomic status and risk of poor health are more likely associated with it.

What are the implications of the results?Disparities in lactation inhibition could be monitored and addressed through tailored support and preventive interventions.

Clara Bermúdez-Tamayo.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsA. Llupià and T. Cobo designed the study. A. Llupià/A. Lladó, I. Torà and J. Puig analysed the data. A. Llupià and J. Puig drafted the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and revision of the manuscript. A. Llupià had primary responsibility for final content and acts as guarantor. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of databases and materialsThe data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Ethical statementThe study was performed according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Since this study is based on routinely collected medical records, informed consent was not obtained. All personal data were dissociated and treated as confidential at all times. The study was approved by the HCB Clinical Research Ethics Committee (HCB/2018/0604).

FundingThe research of JP is supported by MINECO-FEDER Grant PGC2018-098676-B-I00/AEI/FEDER/UE.

Conflicts of interestA. Llupià has participated as investigator in clinical trials of vaccines (Clostridium, Meningococcal and others) promoted by GlaxoSmithKline, Merck and Pfizer.

The authors would like to thank the developers of the HCO registry and all the health care providers who have maintained the database during the last decade. We also thank the Information and Reporting Department and especially Anna Sabater, for sharing the data and Donna Pringle for language revision.