To estimate the prevalence of sexual violence among Catalan adolescents and its associated factors, as well as examining the relationship between experiencing sexual violence and low mood and risky substance use.

MethodCross-sectional study conducted with 5900 adolescents (53.2% girls). The main study variables were having experienced sexual violence and reporting unhealthy behaviours or health problems (low mood, daily tobacco consumption and alcohol and cannabis risky consumption). Prevalence rates were estimated for all variables, and Poisson regression models with robust variance were used to analyse potential associations with independent variables.

ResultsThe prevalence of experienced sexual violence was 30%, with differences between boys (14.1%; 95%CI: 12.8-15.4) and girls (43.3%; 95%CI: 41.6-45.0). Having a minority sexual orientation, early onset of sexual relations, being in a higher academic course, having experienced and exercised bullying, and poor relationship with the parents were associated with experienced sexual violence. Experiencing sexual violence was associated with low mood, daily tobacco consumption and risky alcohol and cannabis consumption for both sexes.

ConclusionsExperiencing sexual violence in adolescence is prevalent, particularly among girls and sexual minorities, and is associated with mental health issues and substance use. The study highlights the need for gender-sensitive healthcare policies that address mental health and social support systems. Comprehensive prevention programs must consider the experiences of gender minorities and the psychosocial factors that contribute to the experience of sexual violence.

Estimar la prevalencia de violencia sexual en adolescentes catalanes y sus factores asociados, y examinar la relación entre experimentar violencia sexual y tener un bajo estado de ánimo y consumo de riesgo de sustancias.

MétodoEstudio transversal con 5900 adolescentes (53,2% chicas). Las variables principales del estudio fueron haber experimentado violencia sexual y declarar comportamientos poco saludables o problemas de salud (bajo estado de ánimo, consumo diario de tabaco y consumo de riesgo de alcohol o cannabis). Se estimaron las prevalencias de todas las variables y se aplicaron modelos de regresión de Poisson con varianza robusta para analizar las asociaciones con variables independientes.

ResultadosUn 30% reportaron experimentar violencia sexual, con diferencias entre los chicos (14,1%; IC95%:12,8-15,4) y las chicas (43,3%; IC95%:41,6-45,0). Tener una orientación sexual minoritaria, el inicio precoz de las relaciones sexuales, un curso académico superior, haber sufrido o ejercido acoso escolar, y la relación con los progenitores, se asociaron con la violencia sexual. Experimentar violencia sexual se asoció con bajo estado de ánimo, consumo diario de tabaco y consumo de riesgo de alcohol o cannabis para ambos sexos.

ConclusionesExperimentar violencia sexual en la adolescencia es prevalente, especialmente entre las chicas y las minorías sexuales, y está asociado con problemas de salud mental y consumo de sustancias. El estudio destaca la necesidad de políticas de salud que aborden la salud mental y los sistemas de apoyo social, con una perspectiva de género. Los programas de prevención deben considerar las experiencias de las minorías de género y los factores psicosociales que contribuyen a experimentar violencia sexual.

Having mental health problems (such as mood disorders), is a frequent condition seen in adolescence. Moreover, these problems usually present more often in girls rather than in boys.1 In a previous study we observed that sexual violence accounted for 36% of low mood problems in adolescent girls,2 highlighting the importance of further studying the relationship of these two variables and how experiencing sexual violence impacts on adolescents mental health, with a gender perspective.

Sexual violence is one of the major public health issues worldwide, especially for women, with an average of 35% who report having experienced some form of sexual violence by their partner or non-partner.3,4 In Spain, the prevalence of non-partner sexual violence is also around 7-9%.5,6 According to data from the sexual violence survey in Catalonia, 11.7% of women aged 15 or older had experienced sexual aggressions, attempted rape, or rape throughout their lives.7 When considering all types of non-partner sexual violence (verbal, such as sexual comments, sexual harassment, and physical), the prevalence rises to 78.8% throughout their lives and 24.2% in the last year.7 Among adolescent boys, although the prevalence of experienced sexual violence is lower than in girls, it is still a concerning issue that warrants study, particularly considering they are minors. In a report by Save the Children in Spain, a prevalence of 14.5% of experienced sexual violence was found among boys aged 14 to 18.8 Regarding the overall data (for both sexes) by autonomous community, it is notable that Catalonia is the second most affected region in terms of reported cases of sexual violence offenses. These type of violences are often experienced in the context of a romantic relationship or in a digital context, especially among girls.9

Mental health problems such as mood disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder have been associated with having experienced sexual violence.5,10,11 A cohort study found that adolescents who had experienced sexual violence have greater risk of suffering psychological distress, higher risk of self-harm and higher risk of attempted suicide.12 Moreover, adolescence is a period accompanied with experimentation and the adoption of some risk behaviours, which can be associated with sexual violence and several health conditions. Health behaviours such as substance use (tobacco, alcohol and cannabis), having mental health problems and having a worse perceived health status have showed an association with experienced sexual violence.4,10,13 These associations have been observed for both boys and girls, with boys showing stronger associations than girls (although the prevalence of experienced sexual violence is higher in girls).10 It is therefore important to consider the gender perspective when studying these variables to explore how these differences may operate.

In fact, it is known that experiencing childhood sexual abuse acts as a precursor to substance use and other sexual risk taking behaviours in adolescence, being mediated by the familial emotional support in some cases.14 Nevertheless, adolescence is a period when peer relationships gain importance, and a detachment of parent relationships is produced. Thus, it is important to consider variables such as family relationships and social support when studying sexual violence in adolescents. Other sociodemographic and psychosocial variables, such as socioeconomic position, having a minority sexual orientation,15 poverty and social vulnerability have been identified as risk factors for experiencing sexual violence,16 and thus should also be considered.

For all the mentioned reasons, in this study, we aimed to analyse how prevalent is sexual violence in Catalan adolescents and which are its associated factors, and to study the relationship between having experienced sexual violence and low mood and risky substance use.

MethodCross-sectional design study using data from the first wave of the DESKcohort project.17 The study population was people aged between 12 and 18 years who were studying 2nd and 4th year of compulsory secondary education (CSE), 2nd year of post compulsory secondary education (PCSE), and intermediate level training cycles (ILTC), in the academic year 2019-2020 in Central Catalonia (from September 2019 until March 2020). All secondary schools in the region (91) were invited to participate. The final sample of secondary schools was 65 (71%), from which 61.5% were public and 38.5% were subsided. The participation rate was comparable between public and subsidized centres, at 74.1% and 67.6%, respectively.17 No significant differences were observed between participating and non-participating centres in terms of ownership or municipality size. In our sample, 33.8% of centres were classified as rural (<10,000 inhabitants) and 66.2% as urban (>10,000 inhabitants), compared to 30.8% rural and 69.2% urban in the non-participating group (p=0.972). Similarly, the distribution of ownership was identical in both groups, with 61.5% of centres being public and 38.5% subsidized. A total of 7319 adolescents were surveyed. We excluded all those who had answered “I don’t know/no answer” or “I prefer not to answer” to the experienced sexual violence items (n=830). Additionally, for variables with less than 10% missing data, cases with missing responses were excluded (n=589), as their small proportion was not expected to significantly impact the estimates or the variables in question. In contrast, for variables with more than 10% missing data, excluding these cases was deemed impractical. Instead, a specific category for missing values was created to ensure their proper handling and inclusion in the analysis (non-respondents). The final sample of the study was 5900 (81%) of adolescents (2759 boys and 3141 girls). Data collection was carried out using a computerised questionnaire based on the Redcap programme18 and was self-administered in the classrooms using touchscreen tablets. The questionnaire was confidential. Parents and adolescents signed an informed consent form authorising participation in the study. The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the UVic-UCC (96/2019).

The first objective was to identify the prevalence of experienced sexual violence and its associated factors, by sex. The dependent variable was having experienced sexual violence. A person was considered to have experienced sexual violence if he/she reported having experienced any of the following forms of violence in his/her lifetime: uncomfortable sexual comments, insistence upon refusal, non-consensual touching, continuous non-consensual touching, forced sexual intercourse and non-consensual penetrative sexual acts (rape) with and/or without physical force.19 Based on the Conceptual Framework of the Social Determinants of Health,20 we selected the following independent variables: sexual orientation (if adolescents identified either as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual or were still questioning it), age of onset of sexual practices, academic year, self-perceived socio-economic level,21 type of municipality, having social support (considered if the adolescent reported that they could talk about a problem or worry with someone, either family member, friends or other relatives), relationship with each parent and finally having experienced and having exercised bullying (Table 1). For the statistical analysis, we calculated the prevalence of having experienced sexual violence and its 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for each independent variable. To analyse the factors associated with experienced sexual violence, Poisson regression models with robust variance were estimated, obtaining prevalence ratios (PR) with their 95%CI.22,23 The crude models were first estimated and then adjusted for the independent variables that showed significance.

Sample description for boys and girls. First wave of the DESKcohort project, 2019-2020.

| Boys (n=2,759) | Girls (n=3,141) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | p | |

| Variables of study | |||||

| Having experienced sexual violence | |||||

| No | 2370 | 85.9 | 1781 | 56.7 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 389 | 14.1 | 1360 | 43.3 | |

| Uncomfortable sexual comments | |||||

| No | 2497 | 90.5 | 1995 | 63.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 262 | 9.5 | 1146 | 36.5 | |

| Insistence upon refusal | |||||

| No | 2667 | 96.7 | 2574 | 81.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 92 | 3.3 | 567 | 18.1 | |

| Cornering between several people | |||||

| No | 2734 | 99.1 | 3043 | 96.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 25 | 0.9 | 98 | 3.1 | |

| Non-consensual touching | |||||

| No | 2659 | 96.4 | 2609 | 83.1 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 100 | 3.6 | 532 | 16.9 | |

| Continuous non-consensual touching | |||||

| No | 2737 | 99.2 | 3042 | 96.8 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 22 | 0.8 | 99 | 3.2 | |

| Rape with physical force | |||||

| No | 2756 | 99.9 | 3124 | 99.5 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 3 | 0.1 | 17 | 0.5 | |

| Rape without physical force | |||||

| No | 2753 | 99.8 | 3107 | 98.9 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 6 | 0.2 | 34 | 1.1 | |

| Sociodemographic and psychosocial variables | |||||

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 2532 | 91.8 | 2377 | 75.7 | <0.001 |

| Homosexual | 45 | 1.6 | 68 | 2.2 | |

| Bisexual | 76 | 2.8 | 374 | 11.9 | |

| Does not know yet | 106 | 3.8 | 322 | 10.2 | |

| Course | |||||

| 2nd of CSE | 968 | 35.1 | 1092 | 34.8 | <0.001 |

| 4th of CSE | 1048 | 38.0 | 1149 | 36.6 | |

| 2nd of PCSE | 565 | 20.5 | 751 | 23.9 | |

| ILTC | 178 | 6.4 | 149 | 4.7 | |

| Socioeconomic position | |||||

| Disadvantaged | 946 | 34.3 | 1113 | 35.4 | 0.519 |

| Medium | 930 | 33.7 | 1018 | 32.4 | |

| Advantaged | 883 | 32.0 | 1010 | 32.2 | |

| Type of municipality | |||||

| Urban | 1510 | 54.7 | 1748 | 55.6 | 0.577 |

| Rural | 1190 | 43.1 | 1318 | 42.0 | |

| Outside of Central Catalonia | 59 | 2.2 | 75 | 2.4 | |

| Interpersonal relationships | |||||

| To have social support | |||||

| Yes | 2217 | 80.3 | 2524 | 80.3 | <0.001 |

| No | 297 | 10.8 | 200 | 6.4 | |

| Non-respondents | 245 | 8.9 | 417 | 13.3 | |

| Relationship with the father | |||||

| Very good/good | 2353 | 85.3 | 2451 | 78.0 | <0.001 |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 324 | 11.7 | 550 | 17.5 | |

| No relationship | 82 | 3.0 | 140 | 4.5 | |

| Relationship with the mother | |||||

| Very good/good | 2529 | 91.7 | 2743 | 87.3 | 0.001 |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 207 | 7.5 | 374 | 11.9 | |

| No relationship | 23 | 0.8 | 24 | 0.8 | |

| Having experienced bullying | |||||

| No | 2474 | 89.7 | 2787 | 88.7 | 0.045 |

| Yes | 194 | 7.0 | 211 | 6.7 | |

| Non-respondents | 91 | 3.3 | 143 | 4.6 | |

| Having exercised bullying | |||||

| No | 2544 | 92.2 | 2967 | 94.5 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 152 | 5.5 | 79 | 2.5 | |

| Non-respondents | 63 | 2.3 | 95 | 3.0 | |

| Health behaviours | |||||

| Age of initiation of sexual practices | |||||

| No sexual relations yet | 1967 | 71.3 | 2155 | 68.6 | 0.044 |

| 13 or younger | 136 | 4.9 | 150 | 4.8 | |

| Over 13 years old | 656 | 23.8 | 836 | 26.6 | |

| Daily tobacco consumption | |||||

| No | 2567 | 93.0 | 2884 | 91.8 | 0.077 |

| Yes | 192 | 7.0 | 257 | 8.2 | |

| Risky alcohol consumption | |||||

| No | 2081 | 75.4 | 2353 | 74.9 | 0.649 |

| Yes | 678 | 24.6 | 788 | 25.1 | |

| Risky cannabis consumption | |||||

| No | 2642 | 95.8 | 3034 | 96.6 | 0.094 |

| Yes | 117 | 4.2 | 107 | 3.4 | |

| Health outcomes | |||||

| Mood | |||||

| High | 2432 | 88.1 | 2309 | 73.5 | <0.001 |

| Low | 327 | 11.9 | 832 | 26.5 | |

CSE: compulsory secondary education; ILTC: intermediate level training cycles; PCSE: post-compulsory secondary education.

The second objective was to study the relationship between having experienced sexual violence and having low mood and risky substance use, also by sex. We created the low mood variable from responses to the questions “How often have you felt: 1) too tired to do things; 2) having trouble sleeping; 3) displaced, sad, or depressed; 4) hopeless about the future; 5) nervous or tense; 6) bored with things?”. For each item, there were five possible responses: from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Then, the results were grouped in two categories: “never”, “almost never”, and “sometimes” (value 0); and “often” and “always” (value 1). Finally, the scores of each item were summed up: a final score of 3 or higher was identified as low mood,2 which has also been used by other authors.2,24–26 Moreover, we used three different types of substance use as dependent variables: a) daily tobacco consumption; b) risky alcohol consumption, measured using the AUDIT-C test, and classifying as risky drinkers those adolescents with scores ≥3;27 c) risky cannabis consumption measured from the CAST test. Risky cannabis users were those adolescents with scores ≥7.28 The main independent variable was having experienced sexual violence. Prevalence and 95%CI of the four dependent variables were calculated for the independent variable. To analyse the association between having experienced sexual violence and each of the health behaviours, Poisson regression models with robust variance with 95%CI22,23 were estimated. Firstly, we estimated the crude models and then we calculated the multivariate models for the independent variable adjusted for course, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, and type of municipality. All analyses were performed stratified for boys and girls. We used STATA v.17 statistical software.

ResultsTable 1 provides a general overview of the sample characteristics, showing that lifetime experience of sexual violence was reported by 14.1% of boys (95%CI: 12.8-15.4) and 43.3% of girls (95%CI: 41.6-45.0). The most frequent type of sexual violence was experiencing unwanted sexual comments, reported by 36.5% of girls and 9.5% of boys (p<0.001), while physical violence (especially rape) was less frequent, with 0.1% of boys and 0.5% of girls (p<0.05). Boys were more likely to report positive family relationships than girls (85.3% vs. 78.0% with their father; 91.7% vs. 87.3% with their mother; both, p<0.001), whereas more girls reported low mood (26.5% vs. 11.9%; p<0.001).

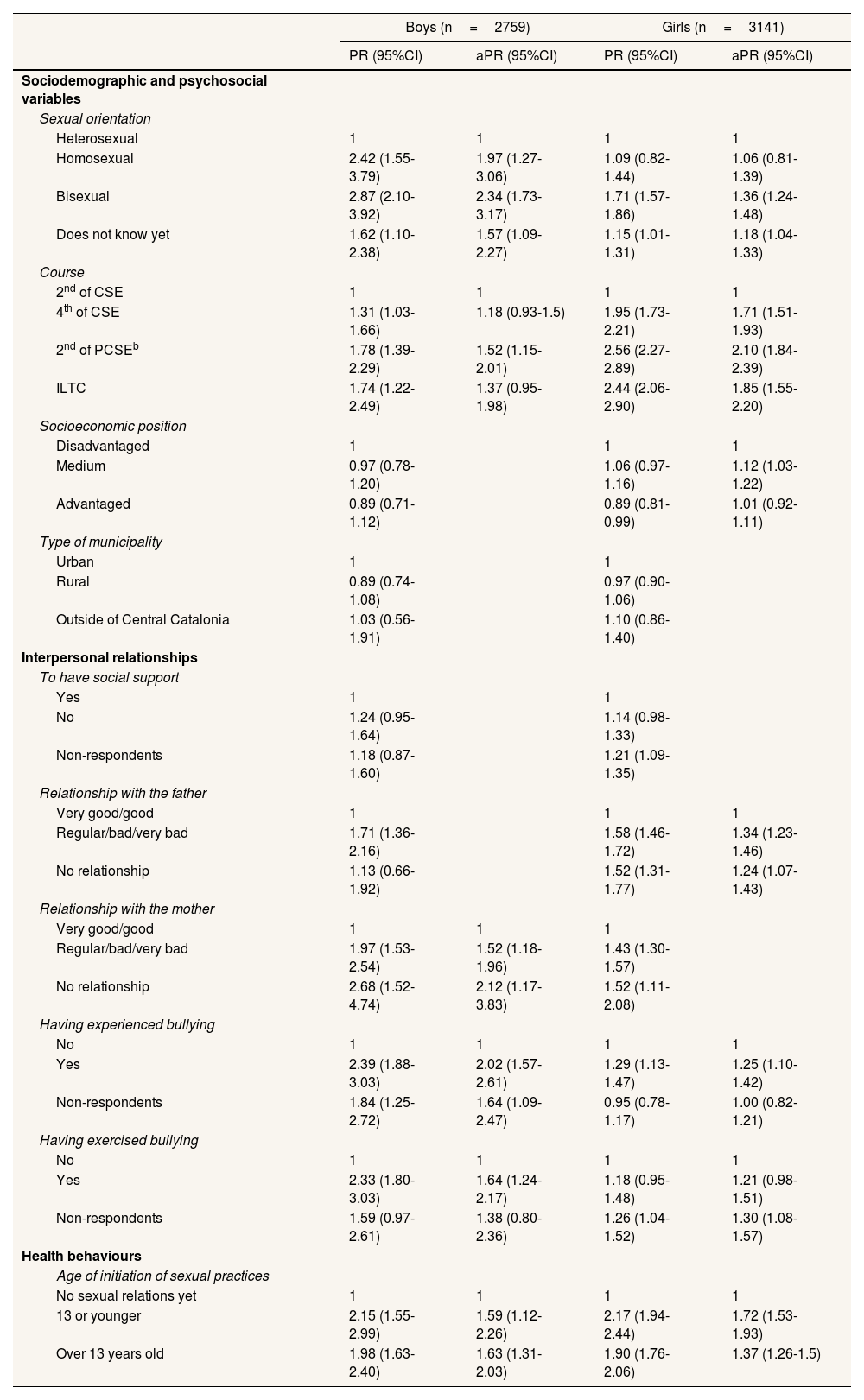

Tables 2 and 3 address the first study objective, assessing the prevalence of sexual violence and associated factors. Heterosexual boys reported a prevalence of sexual violence of 12.8% (95%CI: 11.6-14.2), compared to 31.1% in homosexual (95%CI: 19.4-54.9) and 36.8% in bisexual boys (95%CI: 26.8-48.2). Among girls, bisexual individuals reported a 67.1% prevalence (95%CI: 62.2-71.7), notably higher than the 39.3% in heterosexual girls (95%CI: 37.3-41.3). Moreover, boys in the 2nd of CSE reported a prevalence of sexual violence of 10.6% (95%CI: 8.8-12.7), while in those in the 2nd of PCSE and ILTC it was about 18.9% (95%CI: 15.9-22.4) and 18.5% (95%CI: 13.5-24.9), respectively. Girls in 2nd of CSE reported a 24.2% of experienced sexual violence (95%CI: 21.7-26.8), compared to 47.3% of those in 4th of CSE (95%CI: 44.4-50.2) and 61.9% in 2nd of PCSE (95%CI: 58.4-65.3).

Prevalence of experienced sexual violence in boys and girls according to independent variables.

| Boys (n=2759) | Girls (n=3141) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95%CI) | n | % (95%CI) | |

| Total | 2759 | 14.1 (12.8-15.4) | 3141 | 43.3 (41.6-45.0) |

| Sociodemographic and psychosocial variables | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 2532 | 12.8 (11.6-14.2) | 2377 | 39.3 (37.3-41.3) |

| Homosexual | 45 | 31.1 (19.4-45.9) | 68 | 42.6 (31.5-54.6) |

| Bisexual | 76 | 36.8 (26.8-48.2) | 374 | 67.1 (62.2-71.7) |

| Does not know yet | 106 | 20.8 (14.1-29.5) | 322 | 45.3 (40.0-50.8) |

| Course | ||||

| 2nd of CSE | 968 | 10.6 (8.8-12.7) | 1092 | 24.2 (21.7-26.8) |

| 4th of CSE | 1048 | 13.9 (12.0-16.2) | 1149 | 47.3 (44.4-50.2) |

| 2nd of PCSEb | 565 | 18.9 (15.9-22.4) | 751 | 61.9 (58.4-65.3) |

| ILTC | 178 | 18.5 (13.5-24.9) | 149 | 59.1 (51.0-66.7) |

| Socioeconomic position | ||||

| Disadvantaged | 946 | 14.8 (12.7-17.2) | 1113 | 43.9 (41.0-46.9) |

| Medium | 930 | 14.3 (12.2-16.7) | 1018 | 46.6 (43.5-49.6) |

| Advantaged | 883 | 13.1 (11.1-15.5) | 1010 | 39.3 (36.3-42.4) |

| Type of municipality | ||||

| Urban | 1510 | 14.8 (13.1-16.6) | 1748 | 43.7 (41.4-46.0) |

| Rural | 1190 | 13.2 (11.4-15.2) | 1318 | 42.5 (39.8-45.2) |

| Outside of Central Catalonia | 59 | 15.3 (8.1-26.8) | 75 | 48.0 (37.0-59.2) |

| Interpersonal relationships | ||||

| To have social support | ||||

| Yes | 2217 | 13.5 (12.2-15.0) | 2524 | 41.8 (39.8-43.7) |

| No | 297 | 16.8 (13.0-21.5) | 200 | 47.5 (40.7-54.4) |

| Non-respondents | 245 | 15.9 (11.8-21.1) | 417 | 50.6 (45.8-55.4) |

| Relationship with the father | ||||

| Very good/good | 2353 | 13.0 (11.7-14.4) | 2451 | 38.5 (36.6-40.4) |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 324 | 22.2 (18.0-27.1) | 550 | 60.9 (56.8-64.9) |

| No relationship | 82 | 14.6 (8.5-24.0) | 140 | 58.6 (50.2-66.4) |

| Relationship with the mother | ||||

| Very good/good | 2529 | 13.0 (11.7-14.3) | 2743 | 41.0 (39.2-42.9) |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 207 | 25.6 (20.1-32.0) | 374 | 58.6 (53.5-63.4) |

| No relationship | 23 | 34.8 (18.4-55.7) | 24 | 62.5 (42.2-79.2) |

| Having experienced bullying | ||||

| No | 2474 | 12.5 (11.3-13.9) | 2787 | 42.6 (40.7-44.4) |

| Yes | 194 | 29.9 (23.9-36.7) | 211 | 55.0 (48.2-61.6) |

| Non-respondents | 91 | 23.1 (15.6-32.8) | 143 | 40.6 (32.8-48.8) |

| Having exercised bullying | ||||

| No | 2544 | 13.0 (11.7-14.3) | 2967 | 42.8 (41.0-44.6) |

| Yes | 152 | 30.3 (23.5-38.0) | 79 | 50.6 (39.7-61.5) |

| Non-respondents | 63 | 20.6 (12.4-32.4) | 95 | 53.7 (43.6-63.4) |

| Health behaviours | ||||

| Age of initiation of sexual practices | ||||

| No sexual relations yet | 1967 | 10.9 (9.6-12.4) | 2155 | 33.4 (31.4-35.4) |

| 13 or younger | 136 | 23.5 (17.1-31.4) | 150 | 72.7 (65.0-79.2) |

| Over 13 years old | 656 | 21.6 (18.7-25.0) | 836 | 63.5 (60.2-66.7) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CSE: compulsory secondary education; ILTC: intermediate level training cycles; PCSE: post-compulsory secondary education.

Note: the percentages presented in this table refer to people inside the categories that have experienced sexual violence.

Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios of experienced sexual violence for boys and girls according to sociodemographic variables.

| Boys (n=2759) | Girls (n=3141) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI) | |

| Sociodemographic and psychosocial variables | ||||

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| Heterosexual | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Homosexual | 2.42 (1.55-3.79) | 1.97 (1.27-3.06) | 1.09 (0.82-1.44) | 1.06 (0.81-1.39) |

| Bisexual | 2.87 (2.10-3.92) | 2.34 (1.73-3.17) | 1.71 (1.57-1.86) | 1.36 (1.24-1.48) |

| Does not know yet | 1.62 (1.10-2.38) | 1.57 (1.09-2.27) | 1.15 (1.01-1.31) | 1.18 (1.04-1.33) |

| Course | ||||

| 2nd of CSE | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4th of CSE | 1.31 (1.03-1.66) | 1.18 (0.93-1.5) | 1.95 (1.73-2.21) | 1.71 (1.51-1.93) |

| 2nd of PCSEb | 1.78 (1.39-2.29) | 1.52 (1.15-2.01) | 2.56 (2.27-2.89) | 2.10 (1.84-2.39) |

| ILTC | 1.74 (1.22-2.49) | 1.37 (0.95-1.98) | 2.44 (2.06-2.90) | 1.85 (1.55-2.20) |

| Socioeconomic position | ||||

| Disadvantaged | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Medium | 0.97 (0.78-1.20) | 1.06 (0.97-1.16) | 1.12 (1.03-1.22) | |

| Advantaged | 0.89 (0.71-1.12) | 0.89 (0.81-0.99) | 1.01 (0.92-1.11) | |

| Type of municipality | ||||

| Urban | 1 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 0.89 (0.74-1.08) | 0.97 (0.90-1.06) | ||

| Outside of Central Catalonia | 1.03 (0.56-1.91) | 1.10 (0.86-1.40) | ||

| Interpersonal relationships | ||||

| To have social support | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 1 | ||

| No | 1.24 (0.95-1.64) | 1.14 (0.98-1.33) | ||

| Non-respondents | 1.18 (0.87-1.60) | 1.21 (1.09-1.35) | ||

| Relationship with the father | ||||

| Very good/good | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 1.71 (1.36-2.16) | 1.58 (1.46-1.72) | 1.34 (1.23-1.46) | |

| No relationship | 1.13 (0.66-1.92) | 1.52 (1.31-1.77) | 1.24 (1.07-1.43) | |

| Relationship with the mother | ||||

| Very good/good | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Regular/bad/very bad | 1.97 (1.53-2.54) | 1.52 (1.18-1.96) | 1.43 (1.30-1.57) | |

| No relationship | 2.68 (1.52-4.74) | 2.12 (1.17-3.83) | 1.52 (1.11-2.08) | |

| Having experienced bullying | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.39 (1.88-3.03) | 2.02 (1.57-2.61) | 1.29 (1.13-1.47) | 1.25 (1.10-1.42) |

| Non-respondents | 1.84 (1.25-2.72) | 1.64 (1.09-2.47) | 0.95 (0.78-1.17) | 1.00 (0.82-1.21) |

| Having exercised bullying | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 2.33 (1.80-3.03) | 1.64 (1.24-2.17) | 1.18 (0.95-1.48) | 1.21 (0.98-1.51) |

| Non-respondents | 1.59 (0.97-2.61) | 1.38 (0.80-2.36) | 1.26 (1.04-1.52) | 1.30 (1.08-1.57) |

| Health behaviours | ||||

| Age of initiation of sexual practices | ||||

| No sexual relations yet | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 or younger | 2.15 (1.55-2.99) | 1.59 (1.12-2.26) | 2.17 (1.94-2.44) | 1.72 (1.53-1.93) |

| Over 13 years old | 1.98 (1.63-2.40) | 1.63 (1.31-2.03) | 1.90 (1.76-2.06) | 1.37 (1.26-1.5) |

aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CSE: compulsory secondary education; ILTC: intermediate level training cycles; PCSE: post-compulsory secondary education; PR: prevalence ratio.

Note: The PR presented in this table refer to people inside the categories that have experienced sexual violence. The model has been adjusted for the independent variables associated with sexual violence (p<0.05).

Relational variables also correlated with sexual violence. Both boys and girls with positive relationships with their father or mother reported lower rates of sexual violence. Boys with positive relationships with their father showed a prevalence of 13.0% (95%CI: 11.7-14.4) compared to 22.2% for those with poor relationships (95%CI: 18.0-27.1). Adolescents who experienced bullying reported higher sexual violence prevalence (29.9%, 95%CI: 23.9-36.7 for boys; 55.0%, 95%CI: 48.2-61.6 for girls) than those who did not (12.5%, 95%CI: 11.3-13.9 for boys; 42.6%, 95%CI: 40.7-44.4 for girls). Adolescents who had not engaged in sexual activity reported lower rates of sexual violence: 10.9% of boys (95%CI: 9.6-12.4) and 33.4% of girls (95%CI: 31.4-35.4), compared to those with early initiation of sexual practices, with rates of 23.5% (95%CI: 17.1-31.4) for boys and 72.7% (95%CI: 65.0-79.2) for girls.

Regression models showed that having a minority sexual orientation, being in a higher academic course, having suffered and/or experienced bullying and early onset of sexual practices were associated with sexual violence in both sexes, while having an advantaged socioeconomic position and a poor relationship with the father were associated only in girls, and a poor relationship with the mother only in boys.

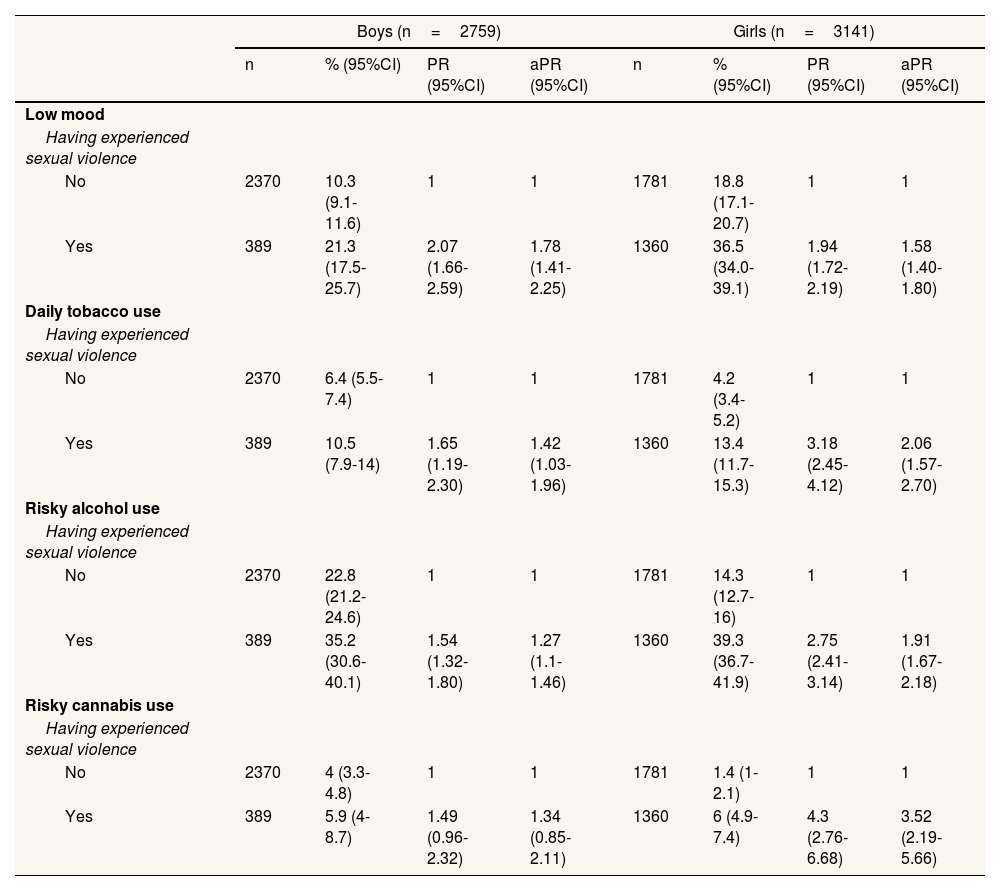

Table 4 presents the prevalence and PR for the four dependent variables of this objective —low mood, daily tobacco use, and risky alcohol and cannabis consumption— based on the main independent variable, sexual violence. The table includes the sample sizes (n) for boys and girls, stratified by whether they experienced sexual violence. For each category of the independent variable (e.g., experiencing or not experiencing sexual violence), the table shows the prevalence and both crude and adjusted PR for each dependent variable. For example, among boys who did not experience sexual violence, 10.3% reported low mood compared to 21.3% among those who did, indicating a significantly worse mood in boys who experienced sexual violence. Regression models use the group not having experienced sexual violence as the reference category.

Prevalence of low mood and substance use and crude and adjusted prevalence ratios according to experienced sexual violence and sexual orientation in boys and girls.

| Boys (n=2759) | Girls (n=3141) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI) | n | % (95%CI) | PR (95%CI) | aPR (95%CI) | |

| Low mood | ||||||||

| Having experienced sexual violence | ||||||||

| No | 2370 | 10.3 (9.1-11.6) | 1 | 1 | 1781 | 18.8 (17.1-20.7) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 389 | 21.3 (17.5-25.7) | 2.07 (1.66-2.59) | 1.78 (1.41-2.25) | 1360 | 36.5 (34.0-39.1) | 1.94 (1.72-2.19) | 1.58 (1.40-1.80) |

| Daily tobacco use | ||||||||

| Having experienced sexual violence | ||||||||

| No | 2370 | 6.4 (5.5-7.4) | 1 | 1 | 1781 | 4.2 (3.4-5.2) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 389 | 10.5 (7.9-14) | 1.65 (1.19-2.30) | 1.42 (1.03-1.96) | 1360 | 13.4 (11.7-15.3) | 3.18 (2.45-4.12) | 2.06 (1.57-2.70) |

| Risky alcohol use | ||||||||

| Having experienced sexual violence | ||||||||

| No | 2370 | 22.8 (21.2-24.6) | 1 | 1 | 1781 | 14.3 (12.7-16) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 389 | 35.2 (30.6-40.1) | 1.54 (1.32-1.80) | 1.27 (1.1-1.46) | 1360 | 39.3 (36.7-41.9) | 2.75 (2.41-3.14) | 1.91 (1.67-2.18) |

| Risky cannabis use | ||||||||

| Having experienced sexual violence | ||||||||

| No | 2370 | 4 (3.3-4.8) | 1 | 1 | 1781 | 1.4 (1-2.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 389 | 5.9 (4-8.7) | 1.49 (0.96-2.32) | 1.34 (0.85-2.11) | 1360 | 6 (4.9-7.4) | 4.3 (2.76-6.68) | 3.52 (2.19-5.66) |

aPR: adjusted prevalence ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CSE: compulsory secondary education; ILTC: intermediate level training cycles; PCSE: post-compulsory secondary education; PR: prevalence ratio.

Note: The models have been adjusted for course, sexual orientation, socioeconomic position, and type of municipality.

Adolescents who experienced sexual violence had higher rates of low mood and risky substance use. Boys with a history of sexual violence reported low mood at 21.3% (95%CI: 17.5-25.7) and daily tobacco use at 10.5% (95%CI: 7.9-14.0). Among girls, the rates were 36.5% for low mood (95%CI: 34.0-39.1) and 13.4% for daily tobacco use (95%CI: 11.7-15.3). Risky alcohol consumption rates were higher in both boys (35.2%, 95%CI: 30.6-40.1) and girls (39.3%, 95%CI: 36.7-41.9) who experienced sexual violence, as well as cannabis use (5.9%, 95%CI: 4.0-8.7 for boys; 4.3%, 95%CI: 2.8-7.4 for girls). Regression models confirmed that experiencing sexual violence was associated with a higher likelihood of low mood and risky substance use across both sexes.

DiscussionThe main findings of this study reveal that 14% of boys and 43% of girls reported experiencing sexual violence in their lifetime. Several factors were associated with an increased risk in both sexes, including having a minority sexual orientation, early onset of sexual activity, higher academic level, and involvement in bullying (both as perpetrator and victim). Additionally, poor relationships with parents were risk factors, being specific to mothers for boys and fathers for girls. Experiencing sexual violence was also associated with low mood and substance use in both boys and girls, though patterns differed, with boys showing higher prevalence of low mood and girls showing higher substance use rates.

Approximately 30% of adolescents reported experiencing sexual violence, with a notably higher prevalence in girls (43.3%) compared to boys (14.1%). This aligns with global data; however, prevalence rates can vary widely across studies due to differences in how sexual violence is defined. For instance, some studies only consider violent physical or sexual behaviours or focus to intimate partner violence, resulting in lower prevalence rates. One European study found a lifetime prevalence of physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence of 7%, which increased to 53.1% when including lifetime psychological-only intimate partner violence.3,4 Similarly, data from the Spanish Survey on Violence Against Women reported a lifetime prevalence of sexual violence at 7.2% among a national sample of women.5 Unlike these studies, our research includes a broad range of sexual violence behaviours, regardless of the perpetrator, providing a more comprehensive assessment of the impact of sexual violence during adolescence.

Having a minority sexual orientation was also associated with a higher prevalence of experienced sexual violence, specifically in bisexual teens. Similar results were found in a nationally representative study conducted in the United States of America, where homosexual and bisexual adolescents experienced twice more sexual violence than their heterosexual counterparts.29 In our study, there were no differences in experienced sexual violence between lesbian and heterosexual girls, whereas homosexual boys had a higher prevalence of experienced sexual violence. These findings could be partly explained because lesbian relationships can be more sexualized due to the patriarchy, and thus suffer less social stigma than gay relationships; nevertheless, this relationship should be further studied to identify what determines these differences. Additionally, we must consider that sexual orientation minorities may suffer from other oppressions, such as externalized and internalized homophobia and biphobia, gender expression or minority stress.30 Therefore, when designing policies and programmes to prevent sexual violence, it is vital to include not only a gender perspective, but also the perspective of sexual orientation minorities.

Other associated factors to experienced sexual violence were having had early onset of sexual relations, being in a high academic course, having experienced or exercised bullying, and having a bad or no relationship with one of their parents. The relationship between an early onset of sexual relations and experiencing more sexual violence is also found by other studies with adolescent population.31–33 One possible explanation is that younger adolescents may be more vulnerable to sexual violence, as they are less able to identify violent behaviour and set boundaries. In addition, perpetrators of sexual violence may see them as a target of people who will trust and depend on them.34 Moreover, a higher academic course (and thus, a higher age), is also associated with a higher prevalence of experienced sexual violence, which can be due to an increased exposure of sexual practices, which it is known to be associated with sexual violence. An association between interpersonal violence (such as bullying) and sexual violence has also been observed, and it should be taken into account that multiple times these types of violence can present together.31,35 According to the social learning theory, a possible explanation of sexual violence is that perpetrators mimic other violent behaviours that they have witnessed or experienced throughout their life.36 Thus, when screening or searching for individuals at risk of experiencing sexual violence, we must contemplate other violent behaviours in their interpersonal relationships.

Social support has an important role when studying sexual violence, since it is known that poor relationships with parents or peers can be predictors for experiencing sexual violence in adolescence.32 Similar results were found in the present study, where a bad or no relationship with the mother was associated to sexual violence in boys and a bad or no relationship with the father was associated to sexual violence in girls. The protective effect of social support with experienced sexual violence in adolescence have also been reported in other studies, since it helps with the development of personal skills to identify violent situations.37

Experiencing sexual violence was associated with having low mood, daily tobacco consumption and risky alcohol and cannabis consumption in both boys and girls. Our results suggest a higher prevalence of low mood in boys in comparison with girls, whereas the opposite is found in relation to substance use. The impact that experiencing sexual violence has on the mental health of an individual is well-known, and it includes a range of consequences such as anxiety and depressive symptoms.5 Moreover, some mental health conditions have been identified as precursors of experiencing sexual violence.32 Thus, when designing sexual violence interventions and prevention programs, addressing mental health issues should be a priority. As for substance use in adolescents who have experienced sexual violence, a systematic review showed that those who had experienced sexual violence were at a higher risk for drug abuse, with girls being more at risk of developing a substance use disorder than boys.38 Moreover, in our study risky cannabis consumption was only associated with experiencing sexual violence in girls. This result is consistent with another longitudinal study, which found that girls who experienced sexual violence were more at risk of consuming cannabis than boys.39 There are several theories that try to explain the association between experiencing sexual violence and substance use. One contemplates substance use as a coping strategy to face the traumatic experiences that they have experienced, whereas another considers that sexual violence leads to poor parent-child attachments, which can also lead to being more impressionable regarding peer pressure and drug use.39

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which prevents causal inference. Furthermore, data on gender identity was unavailable, potentially overlooking differences related to gender identity minorities, who also experience heightened risk.40 Another limitation of this study is the broad categorization of the dependent variable, encompassing diverse forms of sexual violence —from sexual comments to rape— which may reduce specificity in the results. However, understanding factors associated with all types of sexual violence is essential for designing effective prevention programs. Additionally, our findings highlight that even less severe forms of violence, such as sexual comments, can significantly impact adolescent health and behaviour, underscoring the need to address these experiences during this vulnerable developmental stage. The self-reported nature of the data may introduce recall or social desirability bias, though confidentiality of the survey likely mitigated this issue.41 Finally, the questionnaire focused exclusively on in-person sexual violence, excluding other forms such as cyber-sexual violence. Future research should incorporate cyber violence, as it is recognized as one of the most prevalent forms of sexual violence in this age group.42 One strength of this study would be the sample size, which is large and heterogeneous, and the use of validated questionnaires. Moreover, there was an elevated participation of the educational centres of the region, which leads us to believe that our sample is representative of the Catalan adolescent schooled population.

ConclusionsHaving experienced sexual violence is common even in early life stages such as adolescence, especially in girls and in sexual orientation minorities. Moreover, this study highlights the association between sexual violence and mental health problems, including low mood, as well as increased substance use, such as alcohol and cannabis consumption. The implications for healthcare policy and management underscore the necessity of integrating a gender-sensitive approach in designing interventions and preventive strategies for sexual violence, emphasizing the importance of addressing mental health issues and the social support systems available to adolescents. This study highlights the need for comprehensive sexual violence prevention programs that consider not only the experiences of gender minorities but also the psychosocial factors that contribute to both the prevalence of violence and its impact on adolescent health and behaviour.

Availability of databases and material for replicationThe study data are publicly available for other researchers via the project website: https://deskcohort.cat/en/databases/.

Sexual violence in adolescents is frequent and particularly affects women and sexual minorities, with reprecussions on their mental health and risk behaviors, such as substance use.

What does this study add to the literature?The study shows the prevalence and factors associated with sexual violence in adolescents in Catalonia, focusing on the influence of sexual orientation and family support.

What are the implications of the results?The results underscore the need for gender-sensitive health policies and support programs to prevent sexual violence and improve adolescent well-being.

Alberto Lana.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsH. González-Casals: Project administration, conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, visualization and writing (original draft preparation). C. Vives-Cases: conceptualization and writing (reviewing and editing). E. Espelt: conceptualization, validation, supervision, funding acquisition and writing (reviewing and editing). M. Bosque-Prous: conceptualization, supervision and writing (reviewing and editing). E. Teixidó-Compañó: conceptualization and writing (reviewing and editing). G. Drou-Roget: conceptualization and writing (reviewing and editing). C. Folch: conceptualization and writing (reviewing and editing). All authors approve the final version of the present article and confirm that all of its parts have been reviewed and discussed for them to be presented with the best accuracy and completeness.

The authors wish to thank the schools that participated in the study. We also thank the Health and Education Departments of the Catalan Government for facilitating the fieldwork. Finally, we want to acknowledge the DESKcohort project working group (in alphabetical order): Aguilar-Martínez, Alicia; Àlvarez-Vargas, Anaís; Angulo-Brunet, Ariadna; Arechavala, Teresa; Baena, Antoni; Barón-García, Tivy; Bartroli, Montse; Borao, Olga; Caberol, Ariadna; Campoy, Mireia; Clotas, Catrina; Colillas-Malet, Ester; Colom, Joan; Casabona, Jordi; Díaz-Geada, Ainara; Espino, Sandra; Esquius, Laura; Fernández, Esteve; Gontié, Rémi; Jubany, Júlia; Lafon-Guasch, Aina; Majó, Xavier; Manera, Maria; Munné, Carles; Muntaner, Carles; Obradors-Rial, Núria; Puigcorbé, Susanna; Rogés, Judit; Riera, Carlota; Saigí, Francesc; Torralba, Mireia; Torruella, Anna y Vaqué, Cristina. The principal investigator had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This paper is part of the doctoral Dissertation of Helena González-Casals at the Universitat Oberta de Catalunya.