Health promotion (HP) activities should be evaluated both in terms of process and results. However there remains a lack of information regarding the types of HP community interventions that are performed in our country, which of these are based on the best available evidence, and how the evidence available can be translated into HP recommendations for action? Spain does not have a dedicated body to answer such questions. If one existed, its role should be to identify the full range of interventions available to promote health, evaluate them and, in cases where there are positive results, facilitate their transfer and implementation. The aim of this article is to reflect on the need and usefulness of an institution with these functions. It also aims to identify the possible strengths and weaknesses of such an institution and what external experiences could be used in developing it. The discussion draws on the experience of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) highlighting possibilities for collaborative strategies. One might argue that the largely published English language evidence base needs simply to be translated to improve knowledge. However, good practice in HP is based and nurtured within the context where it is to be implemented. Therefore, a strategy to improve practice cannot rely solely on direct translations. Successful evidence-based HP must rely not only on robust scientific evidence but also on a process that ensures appropriate contextualization, that tests methodologies and develops guidance for action appropriate to the country, and that systematizes the process and evaluates the impact once the guidance have been put into practice.

Las actuaciones en promoción de la salud deben ser evaluadas tanto en su proceso como en sus resultados. Sin embargo, se dispone de poca información acerca de qué tipo de intervenciones poblacionales en promoción de la salud se realizan en nuestro contexto, cuáles de ellas se basan en la mejor evidencia disponible y cómo se trasladan las evidencias en promoción de la salud a recomendaciones para la acción. En España no existe un organismo encargado de responder a estas preguntas. Su función debería ser identificar todas las intervenciones, evaluarlas y, en aquellas con resultados positivos, facilitar su transferencia y su implementación. El objetivo de este artículo es reflexionar acerca de la necesidad y la utilidad de disponer de un organismo que tuviera estas funciones; también, identificar las posibles fortalezas y debilidades de esta hipotética institución y sobre qué experiencias se podría ir construyendo. Se comenta la experiencia del National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) y se plantea si podrían llevarse a cabo estrategias de colaboración. Es posible traducir las guías de recomendación que edita NICE para incrementar el conocimiento. Sin embargo, la buena práctica en intervenciones de promoción de la salud se basa y se nutre del contexto donde tienen que ser implantadas. Por tanto, una estrategia para mejorar la práctica no puede basarse solo en traducciones directas; es necesario siempre un proceso de contextualización e ir probando la metodología y construyendo las guías en el propio país, sistematizando el proceso y evaluando el impacto de llevarlas a la práctica.

Health promotion (HP) interventions are all planned actions that aim to increase control of health and its determinants by the population through a range of strategies including: health in all policies, creating favourable environments for health, supporting community action, developing skills and reorienting health services The “eyes” of HP are the “eyes” of the social determinants and equity is key to designing actions aimed at the causes of health inequalities.1

These actions are driven mostly by public health services or primary health care in regional health authorities within Autonomous Communities in Spain. In addition there are action promoted at a municipal level and by the third sector. According to the Spanish General Law of Public Health, all these actions should be evaluated at the level of performance and results, with a timeframe appropriate to the characteristics of the implemented action.2 However evaluation in Spain (and more widely) is seldom central to implementation activity and consequently the public health evidence base remains weak. There is a need therefore in the Spanish context to: understand what types of population-based interventions in public health are being used?; which of these are based on the best available evidence?; how the evidence in health promotion is transferred into recommendations for action?; and which interventions are evaluated and therefore potentially transferable?

Initiatives that try to collect information relating to the above questions do exist in Spain in different ways and in different fields. For example: the long standing network ‘Red Aragonesa de Actividades en Promocion de Salud’;3 and public health observatories (see the Public Health Observatory of Asturias for an illustration of their activities 4). In the field of primary care, the Network of Community Activities5 promoted by the Programme of Community Activities Primary Care (PACAP) of the Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine, provides access to various interventions by topic, age group and population involved. In addition the Spanish Healthy Cities Network6,7 with its focus on the urban environment provides access to municipal health projects by subject area and municipality. In this instance, the area of public health of Barcelona has evaluated a large number of population-based interventions that show improvement in health status.8–10

From these examples, it is fair to say that whilst there is some intervention monitoring and evaluation activity it is often sporadic and irregular. A few years ago the Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality Department (MHSSE),11 launched a call for the registration of all activities that were part of the development of a guide aiming to support local implementation of the Strategy for Health Promotion and Prevention. This provided a framework and recommendations for interventions. In 2014 the MHSSE also initiated a call for good practice examples which were already taking place in the National Health System. The aim being to accredit (or not) existing innovative practices (including health promotion initiatives). The MHSSE call indicated the need for identified projects to confirm that they were based on the best evidence and that they had been properly assessed.12 This highlights that the path towards a systematic and coherent approach to evaluation in theory has already started.

These initiatives have contributed and are contributing to the improvement of HP interventions in Spain, however transferring the evidence from research and evaluations into recommendations for action should not be underestimated, given the complexity of interventions relevant to HP. It is argued here that greater systematic effort is required from this point on to ensure that the resources used are the most appropriate and that the greatest possible benefits can be attained. In fact, in Spain, there is rarely consensus on either what standards are required and/ or the best ways of carrying out HP programmes in practice. As a consequence, there are a variety of programmes and interventions with different orientations and strategies and little knowledge about which ones might be most effective or appropriate. A further complexity is the recognition that each setting and context may require different or adaptations of particular HP interventions. It is therefore not helpful to use fine grained protocols or be as normative as perhaps might be the case in other areas of public health. There are some attempts to identify and promote quality criteria that support the evaluation of good practice. The aim being to make continuous improvements in HP interventions.13 However, the scale of interventions in HP, the multitude of social and health dimensions usually involved and resource scarcity often leads to less than ideal environments to support high performing robust evaluations.

In Spain, although the Ministry of Health has a coordinating role in HP, there is no single institution dedicated to collect, classify and provide information on ongoing population health interventions that have been assessed as evidence base and effective. Such a body could provide a focussed approach to draw on all possible sources of such interventions, support the evaluation of them and, in cases with positive results, facilitate their transfer and implementation. Why does such an institution not already exist in Spain? It may be because neither those in administrative positions, scientific societies, professionals nor the population itself have considered it, or more generally an indifference to the field of HP action. This indifference could be due to:

- •

A lesser priority given to health promotion and primary prevention interventions compared to other public health actions.

- •

A lack of culture of assessment and accountability in the design and development of interventions.

- •

The limited mainstreaming of evidence-based HP and experience in decision making.

- •

A lack of funding for health promotion activities and the lack of specific funds for research and evaluation of interventions.

- •

A lack of political will to give priority measures to HP, especially in the context of economic crisis.

- •

Insufficient expertise in the “know-how” of transforming evidence into action compared to the more prestigious area of ‘knowing’ in traditional epidemiological research.

There are other areas that may undermine the efforts of HP that will not be discussed here but are worthy of note in brief. For example the profile of HP jobs in administrative departments and the requirements to qualify for them; the mismatch between the training required for HP and that which is being taught; and the often inadequate relationship between regional administrations where the public health structures are, and the local municipalities where and with whom HP interventions are being implemented (or where leadership for HP interventions needs to be).

The decentralized structure of the Spanish state, adds a further difficulty to those described above. Specifically, there is no explicit notion of how best to disseminate and share good practice developed in each autonomous territory and what role the Ministry of Health could have in coordinating and facilitating this process. Instead it is often seen as a protagonist of it. If these difficulties can be overcome, the known benefits of HP to improve health and reduce disease for the whole of society can be achieved.14–17

In other countries there are institutions whose remit is to systematically assess what evaluations of HP interventions have be carried out. Some notable examples are: the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) in the UK; the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (EMBC) in Australia; and the US Task Force on Community Preventive Services (USTFCPS) in the United States. There are also specialized institutions in health promotion18 such as the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) United Kingdom; Benchmarking Public Health Ontario and the “City of Hamilton-Public Health and Community Services: Effective Public Health Practice Project” of Canada; and the Foundation for Education and Health Research in Melbourne Australia.

With this background, the aim of this article is to reflect on the need and usefulness of an agency that could assess how best to develop and implement interventions in HP. It will identify the possible strengths and weaknesses of such an institution for Spain. It will also discuss what it is needed to make it feasible and will draw on existing experience in order to know how to build it. Specifically, it will use experience gained from NICE.

NICE is a leader in the field for improving standards in clinical practice, public health and social care. This article will highlight possible strategies to foster collaboration with NICE and other agencies to minimise the duplication of effort.

The General Public Health Act2 proposes the need for a National Centre for Public Health which could provide technical advice and support the evaluation of public health interventions. We advocate for taking advantage of this part of the Act to move things forward. Given the importance of health inequalities this advice would have to be placed in a framework of the social determinants. HP as defined by the Ottawa Charter1 has suffered from a lack of development in Spain and, in general, is almost always equated with health education. Thus ignoring those facets of the Ottawa Charter that promote the need for action in the areas of: political action; social participation; the wider environment and health services.

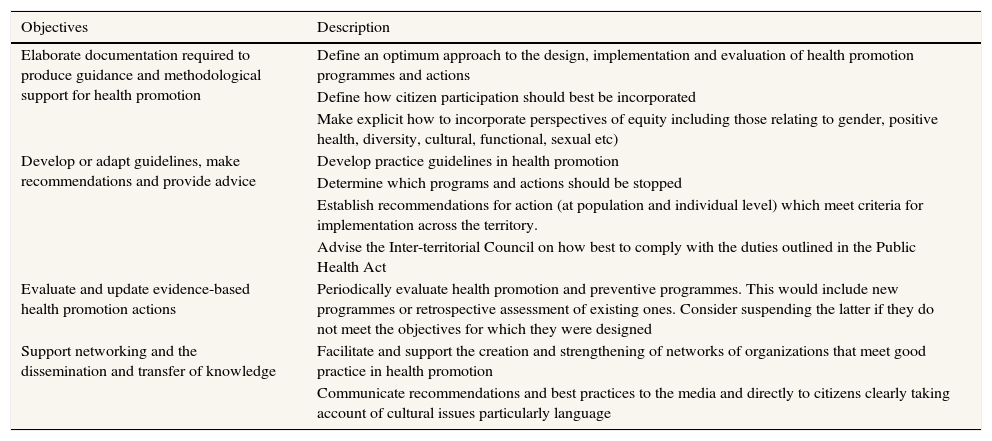

What do we mean by an agency for good practice in health promotion?The Agency should be an independent body supported by the Inter-Territorial Council of the National Health System and the Ministry, with the participation of the Autonomous Communities, scientific societies and civic associations. The main goals would be to provide information to decision makers with a responsibility for health. Its main objectives, as described in Table 1, would be to review evidence and experience, transforming these into recommendations for action and producing guidelines for good practice in the HP field. In addition, it would identify, collect and accredit where appropriate, all those population interventions, set from within and outside the NHS that met previously determined quality criteria. This would allow alignment with the General Public Health Act1 which states that: “The Ministry of Health, Social Policy and Equality Department with the participation of the Autonomous Communities establish and update criteria of good practice for the actions of health promotion and encourage recognition of the quality of the performance”.

Main objectives of an agency for good practice in health promotion.

| Objectives | Description |

|---|---|

| Elaborate documentation required to produce guidance and methodological support for health promotion | Define an optimum approach to the design, implementation and evaluation of health promotion programmes and actions |

| Define how citizen participation should best be incorporated | |

| Make explicit how to incorporate perspectives of equity including those relating to gender, positive health, diversity, cultural, functional, sexual etc) | |

| Develop or adapt guidelines, make recommendations and provide advice | Develop practice guidelines in health promotion |

| Determine which programs and actions should be stopped | |

| Establish recommendations for action (at population and individual level) which meet criteria for implementation across the territory. | |

| Advise the Inter-territorial Council on how best to comply with the duties outlined in the Public Health Act | |

| Evaluate and update evidence-based health promotion actions | Periodically evaluate health promotion and preventive programmes. This would include new programmes or retrospective assessment of existing ones. Consider suspending the latter if they do not meet the objectives for which they were designed |

| Support networking and the dissemination and transfer of knowledge | Facilitate and support the creation and strengthening of networks of organizations that meet good practice in health promotion |

| Communicate recommendations and best practices to the media and directly to citizens clearly taking account of cultural issues particularly language |

The Agency would put special emphasis on capturing HP interventions: “actions aimed at increasing the knowledge and skills of individuals, and to change the social, labour, environmental and economic context, in order to promote their positive impact on individual and collective health (...) acting in different settings: education, health, labour, local and close institutions such as hospitals or residences”2. Thus, the Agency would bring together the best HP interventions, provide information to facilitate effective implementation of evidence-based actions and stimulate the exchange of experience and dissemination of good practice.

The main utility of the Agency would be to identify, classify and disseminate the best and most up to date ways of implementing HP interventions. This type of information and advice will be relevant to the professionals responsible for initiating reformulating or evaluating them. They may also benefit from the accumulated experience of other professionals that could be accrued by the Agency. The Agency would also establish information systems useful to decision-making bodies of the government particularly relating to the cessation of practices that have have not been able to demonstrate their effectiveness.

NICE experienceThe need for evidence based practice is still high on public health agendas both nationally and internationally. The most recent World Health Organisation strategy for health and wellbeing places ‘evidence informed’ decisions at the centre of its implementation plan.19 The original idea behind the evidence based movement in health and health care was to ensure that practice was driven by interventions that had been demonstrated to be effective through an explicit and transparent means. Moreover, that there was an expectation that public sector bodies could demonstrate that their actions could maximise the benefits of the interventions at least cost. This is often translated into the phrase ‘making the best use of limited resources’.

In the UK, the evidence based movement has its roots within medicine. In the early 90's the need to protect patients from potential ‘medical incompetence’ led to the setting up of the Cochrane Collaboration whose principal responsibility was to gather and summarise the best evidence from research to facilitate better decision making processes in the health and more recently social care sector. After over 20 years work the collaboration now consists of a global independent network of more than 37000 contributors (researchers, professionals, patients and carers) from more than 130 countries.20 Systematic reviews of evidence provide a useful starting point for better decision making but they are rarely specific about what actions need to be taken for improvements in health to be made. The NICE in England was given the task of translating evidence into recommendations (evidence based guidance) and after 15 years of its inception produces a range of guidance across the fields of health technologies, clinical practice, public health and most recently social care.21

The systematic synthesis of evidence to support decision making in public health started to emerge in the mid to late 90's. However, it wasn’t until 2005 when NICE took responsibility for producing public health guidance that it started to gain prominence and credibility. The main aim of the guidance is to ensure that programmes and interventions provided by a wide range of public sector organisations have been benchmarked as best quality, that they are good value for money and that they can contribute to reductions in health inequalities.

Whilst NICE isn’t the only organisation responsible for producing evidence based guidance, it is perhaps the most well-known. It has gained credibility with a range of national and international stakeholders as a centre of excellence for supporting evidence based practice. This reputation has been secured over a number of years. As has been argued previously,22 professionals recognise its worth as they are convinced by the principles upon which its work is based. These include the need for guidance to: be based on a comprehensive evidence base; be developed by independent advisors to the organisation; embrace patient, carer and community involvement as integral to the process; and to seek on-going and meaningful consultation with stakeholders during guidance development period.

In addition, the work of NICE also relies heavily on having a robust set of methods and a strong open and transparent process for developing its guidance. Both of these are equally important and work in tandem to ensure that the guidance can be based on the best available evidence, be quality assured and equity focussed.

Morgan20 has already rehearsed some of the experience gained by NICE in producing evidence based guidance over the last 10 years. Some of this experience is reiterated here as it is relevant to the central question of this paper.

Firstly it is important to note that whilst the evidence based public health movement began by following a similar hierarchy of evidence to that of medicine, it soon became apparent that given the complex nature of many public health interventions, a mixed method approach was required to answer not only the ‘what works’ question but how things work in different contexts. In English this is generally known as the ‘horses for courses’ approach –that is the best method for evaluating what needs to be done to improve services should be driven by the question being asked.23 Wimbush and Watson24 provide one useful example of the sorts of questions that may be asked by different stakeholders.

As at June 2016, NICE have produced over 60 pieces of public health guidance that are supportive of effective practice: in contemporary areas of communicable disease prevention: that summarise general approaches to behaviour change; and that identify the characteristics of programmes that work best for different population groups. If one looks across different guidance already produced a number of cross-cutting issues emerge that need to be considered if the interventions deemed to be effective in research can be translated into something that will work in real life. They are: health system characteristics; education and training; and evaluation. Almost all of the public health guidance published to date relies on a specific specification of how ‘the system’ should be configured to support the effective implementation of an intervention. Swann et al.25 summarised many of the system issues that need attention if effective action is to be realised. The guidance also recognises that without appropriate education and training, staff responsible for taking action may either not be aware or have the capacity to follow through with those programmes and interventions that have proven to be effective in research. These issues chime with Godin et al's26 summary of barriers to implementation which he classified as: structural (for example there might be financial disincentives); organisational (relating to the skill mix of professionals or inadequacies of their facilities); individual knowledge and attitudes; and the limits of human processing.

Lastly, but importantly, 10 years’ experience has also shown that there remain deficiencies with the public health evidence base itself. There remains a dearth of good outcome studies answering the questions what works and fewer that answer the question ‘what works, for whom in what circumstances’ and the evidence often doesn’t answer the question you are interested in.27 That said one of the purposes of the NICE production process is to identify gaps in research and some funding agencies are beginning to commission research based on these research recommendations.

Over and above any gaps that relate to the specific topic in focus, a number of other general gaps have emerged. These relate to: problems of the research design itself leading to an inability to deliver unequivocal answers to questions; lack of specification and definition of interventions in the reporting of research that makes replication difficult; and the inability of studies to differentiate relative effectiveness of interventions across different population groups. All these things have implications for the implementation phase of the guidance produced.

NICE public health guidance is not mandatory and to date there have been no formal evaluations that seek to understand the impact on health outcomes. It could be argued that unless sufficient attention is paid to this there is no worth in producing the guidance in the first place. There is therefore an imperative to develop a systematic approach to implementation. The idea is not new. Back in 1997, Grol28 pointed out that evidence based implementation is a necessary accompaniment to evidence based medicine. More recently, Greenhalgh et al.29 have argued that the evidence based movement maybe in crisis and is in danger of causing harm if more attention is not paid to implementation in terms of local feasibility, acceptability and fit with context.

More generally implementation science needs to: take account of the political will and readiness for adoption of evidence and guidance;30 discover how appropriate strategies for change can be developed;31 and knowledge about how to scale up interventions for different contexts and settings.32

In sum, there is much work still be done both in research and in the methods and processes used to translate knowledge from that research into meaningful actions delivered in the context of a supportive environment (or system). Countries wishing to take forward and deliver an evidence based approach should bear this in mind.

Five steps to develop NICE guidelines (NICE, 2012)There are five essential steps involved in producing1 NICE guidelines. They are topic selection; scoping of the topic area; synthesising evidence and developing recommendations; validating the guidance and internal sign off prior to publication.

Firstly, topic selection is a process that helps NICE to decide what its priority areas of work should be. A range of criteria are used to determine how this can be achieved. This priority setting exercise is very context specific. What might be a priority in England may not be a priority in Spain.

Secondly, a scope is developed which uses an inequalities framework to make explicit the need for the guideline at a population and sub population level. The scope also sets out a set of questions that support the development of the research protocol which is required for the next step. A similar sort of exercise could be conducted in order to further develop the specific priority areas that should be taken forward in Spain. Such an activity might provide an initial assessment of the available evidence base that is relevant to the Spanish context.

Thirdly, the development phase of guideline production -the largest part of the process involves: gathering synthesising and quality appraising evidence normally via systematic review; setting up independent committees and developing recommendations for action. It could be argued that the evidence reviews published by NICE and that are available on the NICE website are a sufficient starting point for thinking about how guidance and or implementation activities could be developed. Or the evidence reviews produced to date to produce existing guidelines could be used as a ‘data bank’ of possible interventions to be taken forward within Spain. This could be enhanced by any existing evidence based research that is available in the Spanish language. It is probable that the process of instigating recommendations for actions and or support for implementation activities could be organised and constructed through a similar process to that followed by NICE. This may also include the further elaboration and detailed specification of interventions that have known to be effective – as discussed previously this is an important implementation issue and has not been fully realised as part of the NICE process.

Fourthly, draft guidance is issued for consultation inviting a wide range of registered stakeholders to submit their perspective on the whether the guidance makes sense; is accurate; and implementable. Whatever processes are developed in a Spanish context the principle of consultation and engagement of stakeholders is paramount to the success of work in this field.

Fifthly, the guidance is revised and subjected to internal validation and quality assurance processes before it is finally published. Quality assurance is an important aspect of the process and would have to feature prominently in any organisation responsible for taking evidence based practice forward.

Transferability of NICE guidelinesThe contribution by NICE has stimulated great interest internationally, predominantly in the areas of health technologies and clinical practice, but also increasingly in public health. All NICE work is currently freely available on their website which raises a key question of transferability:

Are the public health guidelines or other documents that NICE provides directly transferable to different contexts of other countries and, therefore, all that is required is to translate them? We think not. Good practice in HP is based in the practice of implementation where interventions are adapted and nurtured by the context within which it is being carried out. Therefore, a strategy to improve practice cannot rely solely on direct translations. There will always be a need for a process of contextualization, testing and building guidelines that are country specific. A systematic process relevant to the relevant infrastructure and HP system will also be required to ensure that the impact of implementing them can be assessed. So a proposal for the future agency should by necessity include a review of an appropriate process for producing guidelines based on the experience gained from NICE (and other external agencies) but adapted to the Spanish context.

NICE guidelines do not guarantee in themselves that improvements in the health of the population will be made. In fact, the direct impact of NICE guidance is not known as there is no formal evaluation of them after they are published. Given the resources required to produce the guidelines it could be argued that the effective implementation of NICE guidance should be supported by a systematic process for putting them into practice and evaluating the results. This process could be one of the tasks to be developed by a future Agency.

ConclusionsHP has been incorporated into the services and actions provided by health services, directly and through intersectoral action. However, there is no culture of critical review, evaluation and search for evidence as is customary in other health practices.

At present most of the published evidence used to produce guidelines is in English. Whilst some learning from the translation of this guidelines is useful adaptation will always be required, Given that good practice in HP is nurtured by the context where it needs to be implemented use of such guidelines would by necessity need to be accompanied by a set of processes and methods which are applicable to county context.

In short, given the wealth of knowledge that exists, any organization wishing to support evidence-based practice must apply this process from the beginning. Implementation science is an emerging field proving that evidence from research alone will not change or improve practice. In the meantime there are many examples of organizations that can support institutions that want to adopt a systematic approach to ensure best practice can support improvements to the population health approach. In this context, people, places and systems have to optimise the ways in which they work together to achieve health impact and gains in the short, medium and long term.

Develop the aspects of the Public Health Act which refer to the evaluation of HP intervention:

- •

Set up a new agency which can strengthen the function of HP through the identification of good practice.

- •

Build guidelines from research in combination with learning from good practice.

- •

Apply an intersectoral perspective recognising that HP requires a wide range of sectors and participants to work together.

- •

Take a collective approach to utilise existing regional organizational experiences in HP evaluation to further develop an evidence based approach in Spain.

Carmen Vives-Cases.

Authorship contributionsQuienes firman la autoría han contribuido en la concepción y diseño del trabajo y han participado en la redacción del manuscrito. Además, han realizado una revisión crítica del artículo y aprueban su versión final.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.