The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoPostpartum hemorrhage is one of the factors causing maternal mortality in Indonesia. In Indonesia, at least 128.000 women suffer from hemorrhage, causing them to death. Data from the Anutapura Public Hospital in Palu showed that the rate of postpartum hemorrhage within 2015–2017 was fluctuated and still caused maternal mortality. This study aimed to determine the risk factors of the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in maternal mothers at Anutapura Public Hospital, Palu.

MethodThe type of study was observational with a case-control approach. The subject of the study was mothers having a postpartum hemorrhage. The total sample of this study was 50 people as the case group and 100 people as the control group by adjusting the types of labor. Sampling was done using a total sampling technique. The data were analyzed using an odds ratio test with α=5%.

ResultThis study showed that anemia (OR=2.874 and CI=1.421–5.812), parity (OR=3.995 and CI=1.952–8.174), age (OR=2.874 and CI=1.421–5.812) were the risk factors of postpartum hemorrhage in women.

ConclusionThe anemia, parity, and age are the risk factors of postpartum hemorrhage in women. The importance of increasing ANC (antenatal care) visits is to control maternal and fetal health and provide information through a medical consultation about the importance of planning a good pregnancy.

The success of maternal health attempts can be seen from the indicator of Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR). MMR is the total maternal mortality during pregnancy, labor, and puerperium caused by pregnancy, labor, and puerperium or the management, but it is not because of the other causes such as accident or fall per 100,000 live births. Then, maternal mortality can be changed into the ratio of maternal mortality, and it is expressed per 100,000 live births by dividing the mortality rate by the general fertility rate. By using this method, it can obtain a maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 births.1

The maternal mortality rate is one of the vital indicators for global Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) that had ended in 2015, which was continued by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) up to 2030. According to the interpretation of the goals and the global SDGs for the indicators of a healthy and prosperous life, in 2030, the maternal mortality rate should be decreased by up to less than 70 per 100,000 live births.2

According to the WHO report in 2014, the Maternal Mortality Ratio in the world was 289 per 100,000 live births, 179 per 100,000 live births for North Africa, and 16 per 100,000 live births for Southeast Asia. The Maternal Mortality Ratio in Asian countries was as follows 214 per 100,000 live births for Indonesia, 170 per 100,000 live births for the Philippines, 160 per 100,000 live births for Vietnam, 44 per 100,000 live births for Thailand, 60 per 100,000 live births for Brunei, and 39 per 100,000 live births for Malaysia. Alternatively, WHO estimated that in 2015, the total maternal mortality reached around 303 per 100,000 live births globally. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in some developing countries reached 239 per 100,000 live births that were 20 times greater than that of the developed countries. The developing countries contributed around 90% or 302 per 100,000 live births from the estimated maternal mortality ratio that happened in 2015.3

The profile of Health Agency in Central Sulawesi in 2018 showed the primary four causes for maternal deaths, including hemorrhage of 30.3%, pre-eclampsia of 27.1%, infection of 7.3%, and other factors that caused a direct maternal death of 35. 3%, such as cancer, kidney disease, heart disease, or other diseases suffered by the mothers.4

Based on the data collected from the Health Agency of Palu City in the annual report within 2015–2017, it could be found a case of maternal mortality caused by hemorrhage, whereby in 2015, it was collected 22 cases of maternal mortality with 326/100,000 live births, 11 cases of maternal mortality with 158/100,000 live births in 2016, and 11 cases of maternal mortality with 156/100,000 live births in 2017. Besides the data of mortality rate, there was data about the factors causing maternal mortality from 2015 to 2017; the factors causing maternal mortality were hemorrhage of 63.63%, followed by pre-eclampsia of 22.72%, infection of 4.5%, and other factors of 9.09%. Moreover, the maternal mortality rate based on the place of death was shown as follows; 66.30% at Regional Public Hospital (RSUD), which Anutapura Public Hospital in Palu was the place with the highest maternal mortality rate, namely five deaths out of 11 deaths in 2017.

The data from Anutapura Public Hospital in Palu showed that the incidence rate of postpartum hemorrhage in 2015 was 36 cases from 3,412 birth mothers, 58 cases from 3,243 birth mothers in 2016, while in 2017, the rate was 50 cases from 2,804 birth mothers. Even though there was a decline, postpartum hemorrhage still becomes the key factor causing a high rate of maternal mortality.5,6

Most maternal mortality cases happen 24h after giving birth, and postpartum hemorrhage is one of the direct causes of maternal mortality. Postpartum hemorrhage is an unexpected leading cause of maternal mortality in the world. The hemorrhage case in Indonesia is estimated at around 14 million. There is, at least, 128,000 women experiencing hemorrhage until it causes deaths annually. Postpartum hemorrhage is the most frequent factor causing maternal mortality. It is the post-delivery bleeding happened within the first 24h following childbirth.7

Postpartum hemorrhage is excessive bleeding in the genital tract after the birth of a baby or abortion and until six weeks after that. The primary postpartum hemorrhage refers to bleeding within 24h following birth, while the secondary postpartum hemorrhage is the bleeding occurred after 24h (and in 6 weeks).7 Many risk factors cause postpartum hemorrhage, such as having a pregnancy complication grade 3 in the medical history previously, previous cesarean section, multiple pregnancies, primigravida, high parity, anemia, surgical labor, prolonged obstructed labor, precipitate parturition, placenta previa, abruptio placentae.8 This study aimed to know the risk factors of the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers at Anutapura Public Hospital, Palu, in 2017.

MethodThe type of this study was a case–control study with an analytical survey as the approach to know the risk factors of the dependent variable and independent variable. The dependent variable in this study was postpartum hemorrhage, while the independent variable was the factors that might risk resulting in the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, namely Anemia, Parity, and age.

The type of data in this study was secondary data. The data in this study were collected from the patients’ medical records having complete data in 2017. The data analysis was done using univariate and bivariate analyses by presenting the results in the form of tables.

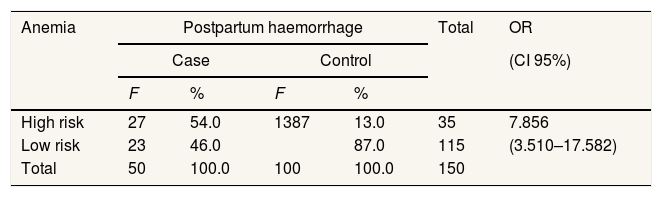

ResultsThe result of bivariate analysis for the risk factors of the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers at Anutapura Public Hospital, Palu, in 2017 is presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows the respondents with postpartum hemorrhage are those with a high risk of anemia; the total is 54.0% that is higher than the total patients with a low risk of anemia of 46.0%. Meanwhile, the respondents with no postpartum hemorrhage are mostly non-anemic of 87.0% that is higher than the total respondents who are anemic of 46.0%.

Based on the statistical test, it was collected an OR value of 7.8 at 95% CI of 3.510–17.582. It indicated that the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in anemic birth mothers was 7.8 times greater than that of non-anemic birth mothers. It is because the OR value was more than one, and the lower limit and the upper limit were more than 1, so anemia was the significant risk factor in postpartum hemorrhage.

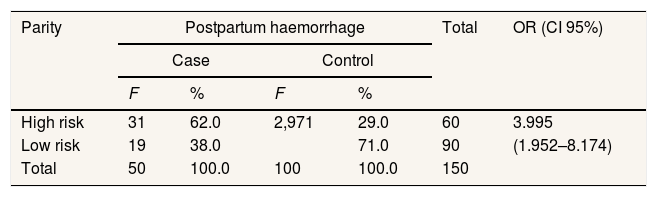

Table 2 shows that the total respondents with postpartum hemorrhage having parity of more than 3 are 62.0%, and the total of those having parity of around 2–3 is 38.0%. Meanwhile, the total respondents with no Postpartum hemorrhage having parity of around 2–3 is 71.0%, and the total respondents having parity of more than 3 is 29.0%.

Based on the statistical test, it was obtained an OR value of 3.9 at 95% CI of 1.952–8.174, indicating that the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers with parity of more than 3 is 3.9 times greater than the birth mothers having parity of around 2 to 3. It is because the OR value was more than one, and the lower limit and the upper limit were more than 1, so parity was the significant risk factor in postpartum hemorrhage.

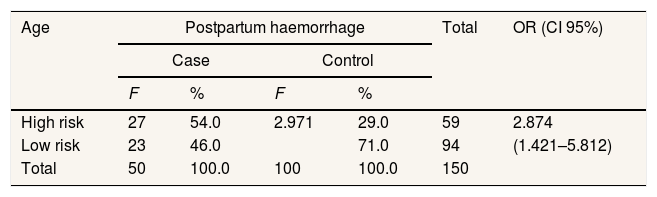

Table 3 shows the total respondents with Postpartum hemorrhage in mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old is higher (54.0%) than that of the mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old (46.0%). Meanwhile, the total respondents with no postpartum hemorrhage in the mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old (71.0%) is higher than that of the mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old (29.0%).

Based on the statistical test, it was obtained an OR value of 2.8 at 95% CI of 1.421–5.812, indicating that the risk of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old is 2.8 times greater than that of the birth mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old. It is because the OR value was more than one, and the lower limit and upper limit were more than 1, so age was the significant risk factor of postpartum hemorrhage.

DiscussionAnemia and the risk of postpartum hemorrhageAnemia can weaken the mothers’ immunity and increase the frequency of complications while pregnant and labor. Anemia also causes an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage.8 Getting tired easily in anemic patients is caused by the energy metabolism by the muscles that cannot move perfectly due to lack of oxygen. Based on the result of the analysis of the risk of anemia in this study, it was obtained an Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 7.8, indicating that the anemic birth mothers have the risk of postpartum hemorrhage of 7.8 times greater than the non-anemic birth mothers.9

These research findings are in line with the study conducted by Sentilhes et al. that the anemic birth mothers have a risk of postpartum hemorrhage 4.8 times greater, indicating that there is a relationship between anemia and the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers. 10

During pregnancy, more iron is needed to produce red blood cells because the mothers should fulfill the fetal needs and themselves; also, during the labor process, the mothers need hemoglobin intake to provide energy, so the uterine muscle can have a good contraction.11

Parity and the risk of postpartum hemorrhageThe mothers with high parity will affect the condition of the mothers’ uterus because the more frequent the mothers to give birth, the reproductive function decreases, the uterine muscle will be too tight, and it cannot have a normal contraction; so, it allows a high possibility of having postpartum hemorrhage.12

Based on the result of analysis for the risk of parity in this study, it was obtained an Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 3.9, indicating that the birth mothers with parity of more than 3 had a risk of postpartum hemorrhage 3.9 times greater than that of the birth mothers with parity of around 2–3. In this study, it was recorded that from 50 postpartum hemorrhage cases, 31 of them were the mothers with parity of more than 3 (high risk), while the total anemic mother with hemoglobin levels of less than 11g/dl (high risk) was 27 and the total mother at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old (high risk) was 27 people.

The research findings showed that the total respondent experiencing postpartum hemorrhage with parity of more than 3 (62.0%) was higher than those with parity of around 2-3 (38.0%), while the total respondent with no Postpartum hemorrhage having parity of around 2–3 (71.0%) was higher than those with parity of more than 3 (29.0%).

The result of this study is in line with Cortet et al. and Janighorban et al. stating that primipara and multipara women lose their blood as much as in postpartum hemorrhage; in this case, multipara women lose their blood more than nulliparous women (nullipara). Parity has a role in causing the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage because, in each pregnancy and labor, there is a change in the uterine muscle fiber that can decrease the uterus ability to have a contraction.13,14 Consequently, it is difficult to press the opened blood vessels after the placenta detaches. The risk of having the incidence will increase after the third labor or more, causing postpartum hemorrhage.

Age and the risk of postpartum hemorrhageThe best age for women to get pregnant with low risk is around 20–35 years old because they are in a healthy reproductive phase. Maternal mortality in pregnant mothers and birth mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old will significantly increase because they are exposed to the complication both medical and obstetric; it can harm the mothers’ lives; it is the reason why age becomes the cause of postpartum hemorrhage.8,15

In this study, it was recorded that from 50 postpartum hemorrhage cases, 27 of them were the mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old (high risk). Also, the total anemic mother with hemoglobin levels of less than 11g/dl was 27 people (high risk), and the total mother with parity of more than 3 (high risk) was 31 people. The result of this study showed that the respondents experiencing postpartum hemorrhage were mostly mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old (54.0%). The total was higher than that of the mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old (46.0%). The respondents with no postpartum hemorrhage were mostly mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old (71.0%). It was higher than mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old (29.0%). Based on the result of the analysis for risk of age in this study, it was collected an Odds Ratio (OR) with 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 2.8, indicating that birth mothers at the age of below 20 years old and over 35 years old had a risk of postpartum hemorrhage 2.8 times greater than the birth mothers at the age of around 20–35 years old.

The results of this study are in line with several previous studies that women giving birth under the age of 20 years and over 35 years have a higher risk of postpartum hemorrhage.16–18 It is also in line with Bai et al. and Nur et al. that age is strongly connected with the readiness of the mothers in reproduction. Women at the age of below 20 years old are still at the growth and development stages, so the pregnancy condition will make them should share with the fetus they are expecting to fulfill the nutrition needs.19,20 Conversely, mothers aged over 35 years begin to show the effects of aging, such as often having hypertension and diabetes mellitus, which can prevent fetal food from entering the placenta.

Besides, postpartum hemorrhage causing maternal mortality in pregnant women that gives birth at the age of below 20 years old is 2.5 times greater than postpartum hemorrhage that happened at the age of around 20–35 years old. Postpartum hemorrhage increases again after the age of around 30–35 years old.21,22

ConclusionBased on the study above, it can be concluded that anemia, parity, and mothers’ age are the risk factor of the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage in birth mothers. Anutapura Public Hospital of Palu City is expected to make the result of this study as a reference in designing the preventive program in birth mothers having a risk factor in experiencing postpartum hemorrhage and the mitigation program for the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage, so it can decrease the complication caused by the incidence.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.