There are small isolated human groups within our communities with a lot of possibilities of being involved in exclusion processes. The aim of this study is to show the quality of life related to health (HRQL) and how it is influenced by certain factors on two teenagers groups at risk of exclusion in Melilla, as they represent approximately 10% of young people of their age. The first group is Unaccompanied Foreign Minors (UFMs) which represent a new migration currently in Europe; the second group, students in Initial Professional Qualification Programs (IPQP). The study was developed during 2010 in Melilla (Spain), City of a multicultural character located on the Mediterranean coast of North Africa which has a land border with Morocco, affected by migration.

Therefore, we designed a cross-sectional study and a probability sampling by conglomerates was performed, with a single-stage procedure and with a second stage of simple randomness. From the study population (169 UFMs plus 211 IPQP), 172 surveys were conducted, of which 28 were discarded remaining 144 (71 UFMs plus 73 IPQP). The HRQOL was measured using the Spanish version of Vécu et Santé Perçue de l’Adolescent (VSP-A).1 A descriptive statistical analysis (Student's t, effect size, d to Cohen and correlation r) was performed and a multivariate analysis was included. All data were analyzed using SPSS and Excel.

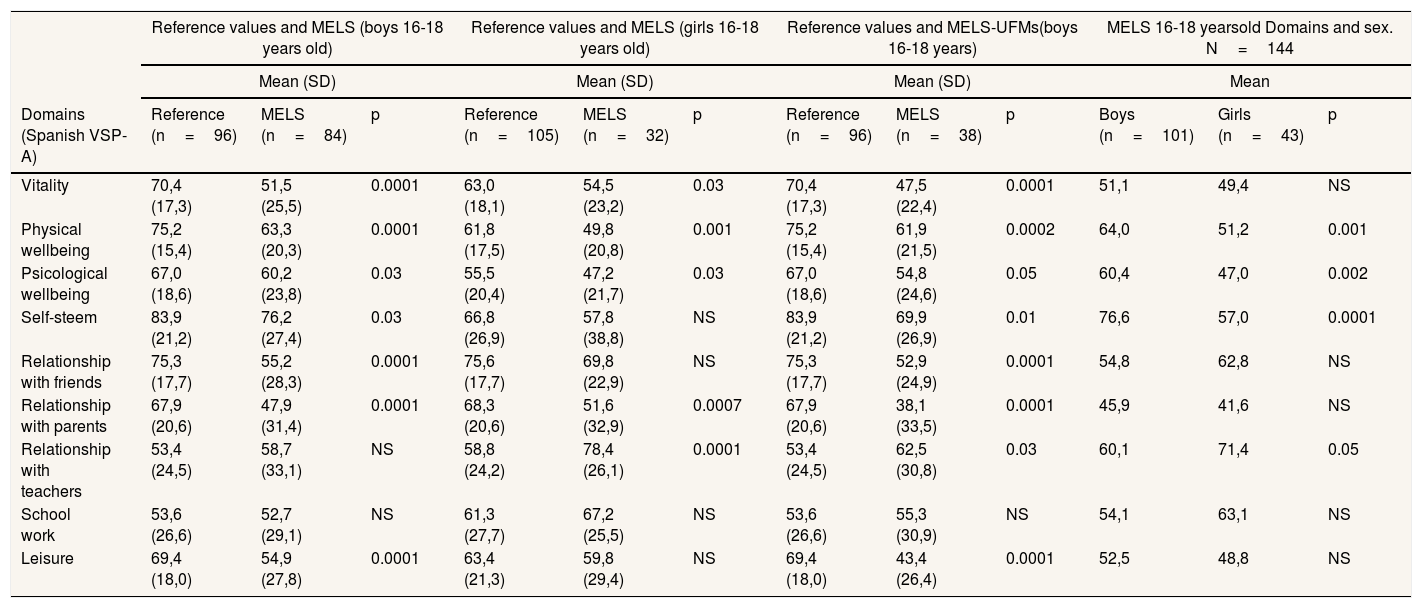

The characteristics of the sample were briefly the following: mainly boys (71,7%) with a median age of 16,3 years, 56,3% born in Morocco, who largely came from broken homes (Loss of a parent or separated: IPQP 25,3%, UFMs 50%. and poor parental level of education as they had no studies or did not finished primary school: IPQ 30%, UFMs 53,7%). All domains had an acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α range, 0.75 to 0.84). The results show scores significantly lower than reference population in vitality, physical, psychological wellbeing and relationship with parents. UFMs lower scores. Significantly lower scores of girls in physical, psychological and self-esteem (Table 1). The variables associated with HRQL in the multivariate analysis were: sex, age, religion, sports and the prevalence of consumption in the last 30 days of tobacco, alcohol and tranquilizers.

Comparison results of means between two groups (t de Student). Comparison results in each domain and sex.

| Reference values and MELS (boys 16-18 years old) | Reference values and MELS (girls 16-18 years old) | Reference values and MELS-UFMs(boys 16-18 years) | MELS 16-18 yearsold Domains and sex. N=144 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean | |||||||||

| Domains (Spanish VSP-A) | Reference (n=96) | MELS (n=84) | p | Reference (n=105) | MELS (n=32) | p | Reference (n=96) | MELS (n=38) | p | Boys (n=101) | Girls (n=43) | p |

| Vitality | 70,4 (17,3) | 51,5 (25,5) | 0.0001 | 63,0 (18,1) | 54,5 (23,2) | 0.03 | 70,4 (17,3) | 47,5 (22,4) | 0.0001 | 51,1 | 49,4 | NS |

| Physical wellbeing | 75,2 (15,4) | 63,3 (20,3) | 0.0001 | 61,8 (17,5) | 49,8 (20,8) | 0.001 | 75,2 (15,4) | 61,9 (21,5) | 0.0002 | 64,0 | 51,2 | 0.001 |

| Psicological wellbeing | 67,0 (18,6) | 60,2 (23,8) | 0.03 | 55,5 (20,4) | 47,2 (21,7) | 0.03 | 67,0 (18,6) | 54,8 (24,6) | 0.05 | 60,4 | 47,0 | 0.002 |

| Self-steem | 83,9 (21,2) | 76,2 (27,4) | 0.03 | 66,8 (26,9) | 57,8 (38,8) | NS | 83,9 (21,2) | 69,9 (26,9) | 0.01 | 76,6 | 57,0 | 0.0001 |

| Relationship with friends | 75,3 (17,7) | 55,2 (28,3) | 0.0001 | 75,6 (17,7) | 69,8 (22,9) | NS | 75,3 (17,7) | 52,9 (24,9) | 0.0001 | 54,8 | 62,8 | NS |

| Relationship with parents | 67,9 (20,6) | 47,9 (31,4) | 0.0001 | 68,3 (20,6) | 51,6 (32,9) | 0.0007 | 67,9 (20,6) | 38,1 (33,5) | 0.0001 | 45,9 | 41,6 | NS |

| Relationship with teachers | 53,4 (24,5) | 58,7 (33,1) | NS | 58,8 (24,2) | 78,4 (26,1) | 0.0001 | 53,4 (24,5) | 62,5 (30,8) | 0.03 | 60,1 | 71,4 | 0.05 |

| School work | 53,6 (26,6) | 52,7 (29,1) | NS | 61,3 (27,7) | 67,2 (25,5) | NS | 53,6 (26,6) | 55,3 (30,9) | NS | 54,1 | 63,1 | NS |

| Leisure | 69,4 (18,0) | 54,9 (27,8) | 0.0001 | 63,4 (21,3) | 59,8 (29,4) | NS | 69,4 (18,0) | 43,4 (26,4) | 0.0001 | 52,5 | 48,8 | NS |

MELS: acronym of this study; NS: not significant; SD: standard deviation.

These observations are consistent with previous findings that have used the same questionnaire in Spain 2 as in Belgium 3 (n=158) with immigrant adolescents. Our study provides HRQL in UFMs. The quantitative study approach may complement other qualitative ones as the performed in the Basque Country (Spain) 4 with a sample of 60 UFMs. The difficulty of the study and approach to this group lies, among others, in the dispersion due to the different flats host and centers where they live. They can explain smaller sample sizes, such as a study of Hodes et al.5 (n=78 UFMs between 12 and 18 and 35 foreign children accompanied), or Gilgen et al. (2005) in Basel.

Multiple linear regression analysis corroborates findings already discussed in relation to sex, providing moreover the possible influence of the consumption of certain easy to get substances by adolescents such as tobacco and alcohol, in the different domains of HRQL, reducing their significantly scores. It also shows the positive influence that certain adolescent's attitudes have in HRQL such as religiosity and sports.

The main limitation of this study is the one inherent in cross-sectional studies.

The results reflect the need to design preventive programs1: programs of health promotion, related to leisure, peer relationships, interpersonal relationships, self-esteem, empowerment and autonomy of women, and such as the action on conflicts experienced in relationship with their parents. These results provide clues too on how to investigate other youth groups.

FundingNone.

Authorship contributionsD. Castrillejo has designed the study and has performed the analysis. D. Castrillejo, C. Muñoz-Bravo, A. García-Rodríguez, J. Ruiz and M Gutiérrez-Bedmar have participated in the analysis, drafting and discussion of the results. All authors have approved the final version of the article.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We appreciate the cooperation of the regional ministry of social welfare and health of Melilla, principals, teachers, staff of the centers and youth participants involved in it.

«Abandoning children on the streets involves placing delayed effect bombs on the heart of cities» «Laisser des enfants dans la rue revient à poser des bombes à retardement au cœur des villes». Tessier S, director. L’enfant des rues et son univers: ville, socialitation et marginalité. Paris: Syros; 1995. 227p.