To analyse to what extent pregnant women remembered having received health advice regarding alcohol consumption during pregnancy, what the message they perceived was and whether there is social inequality in this regard.

MethodA cross-sectional descriptive study was performed with a sample of 426 pregnant women (in their 20th week of pregnancy) receiving care in the outpatient clinics of a university hospital in a southern Spanish city (Seville). The data were collected through face-to-face structured interviews carried out by trained health professionals.

Results43% of the interviewed women stated that they had not received any health advice in this regard. Only 43.5% of the sample remembered having received the correct message (not to consume any alcohol at all during pregnancy) from their midwife, 25% from their obstetrician and 20.3% from their general practitioner. The women with a low educational level were those who least declared having received health advice on the issue.

ConclusionThe recommended health advice to avoid alcohol consumption during pregnancy does not effectively reach a large proportion of pregnant women. Developing institutional programmes which help healthcare professionals to carry out effective preventive activities of foetal alcohol spectrum disorder is needed.

Analizar en qué medida las gestantes recuerdan haber recibido asesoramiento sanitario sobre el consumo de alcohol durante el embarazo, cuál es el mensaje percibido y si existe desigualdad social al respecto.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio transversal descriptivo con 426 mujeres en su semana 20 de embarazo en las consultas externas de un hospital universitario de Sevilla (España). Los datos se recopilaron mediante entrevistas estructuradas cara a cara realizadas por profesionales sanitarias entrenadas.

ResultadosEl 43% de las entrevistadas afirmaron no haber recibido consejo sanitario alguno al respecto. Solo el 43,5% dijeron que habían recibido el mensaje correcto (no beber absolutamente nada de alcohol durante el embarazo) por parte de la matrona, el 25% por el obstetra y el 20,3% por el médico de atención primaria. Las embarazadas con menor nivel educativo fueron las que menos refirieron haber recibido asesoramiento sanitario sobre el tema.

ConclusiónEl consejo sanitario adecuado (evitar todo consumo de alcohol durante el embarazo) no llega de manera efectiva a una amplia proporción de las gestantes. Es necesario desarrollar programas institucionales que posibiliten que los profesionales sanitarios puedan llevar a cabo con eficacia actividades preventivas de los trastornos del espectro alcohólico fetal.

Prenatal alcohol exposure can cause permanent brain damage1–3 which may lead to a wide range of cognitive deficits,4 motor abnormalities5 and behavioural disorders, such as the difficulty to self-regulate,6 difficulty in handling stress and depression.7 Prenatal alcohol exposure related brain damage is usually accompanied by abnormal facial features, congenital deformities and a fetal growth restriction.8,9 These problems are all collectively included under the term “fetal alcohol spectrum disorders” (FASD),10 and tend to be lifelong problems. Alcohol may be teratogenic from the first weeks of pregnancy,7 before the woman is aware of the pregnancy. Its epigenetic action can also result in cardiovascular diseases, endocrine dysfunction and other health problems that appear in adulthood.11 Additionally, prenatal alcohol exposure leads to the risk of miscarriage12 and premature delivery.13

The World Health Organization (WHO) European Region has the highest alcohol consumption per capita in the world. Within these countries, 59.9% of women consume alcoholic drinks.14 In Spain, specifically, around two thirds of women between 15 and 44 years of age consume alcohol.15

Prenatal alcohol exposure is a pandemic health problem.16 There is no precise estimate of alcohol consumption by pregnant women in the European Union. The studies carried out differ in their methodology, which makes comparing results difficult.17 Some studies carried out in European countries show a particularly high prenatal alcohol exposure prevalence (≥40%), namely in Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Russia, Ukraine and the United Kingdom.16 In a study carried out in 11 European countries with samples of pregnant and puerperal women recruited on websites, 15.8% said they had consumed alcohol during pregnancy.17 In turn, the prevalence of alcohol consumption during pregnancy in the whole WHO European Region was estimated at 25.2%.16 In Barcelona, when analysing metabolites in biological samples (meconium), 45% of pregnant women who received care at a public hospital had consumed alcohol during pregnancy.18,19

Prenatal alcohol exposure is considered the leading preventable cause of birth defects and developmental disabilities.20 FASD is preventable by avoiding alcohol consumption from the very start of pregnancy (in practical terms, from even before the start of pregnancy). As no safe alcohol consumption level during pregnancy has been established,21 clinical practice guidelines in Australia22 and Denmark,23 as well as in a growing number of countries, were modified in order to recommend that health professionals promote total avoidance of alcohol consumption throughout pregnancy, in line with the principle of precaution. The American Academy of Pediatrics formulated equivalent recommendations.10

Healthcare professionals who provide care for women of a childbearing age and pregnant women can have a decisive influence on the prevention of FASD.24–26 In general, the recommendations of healthcare professionals regarding alcohol consumption during pregnancy are seen as credible by women.25,27 However, it has also been detected that pregnant women (in particular with higher levels of education) are disoriented by the potentially contradictory information in the messages received from different healthcare sources and demand coherence and accuracy in the available information.27

Studies on the extent to which pregnant women are receiving health advice on alcohol consumption are scarce.28 The messages received in this regard from health professionals have been explored mainly through qualitative studies with small samples.27,29 Researching these issues with a random sample of pregnant women who received care in a health community area could be useful for detecting whether or not the prevention of FASD must be revitalised or reoriented within the public health system. This would also be useful for identifying specific sectors of pregnant women who, for socio-educational reasons, experience particular difficulties when being informed of the risks of consuming alcohol during pregnancy. Bearing these aims in mind, a cross-sectional descriptive study was carried out on a representative sample of pregnant women receiving health care in the outpatient clinics of a public university hospital of Seville, southern Spain, a country with a traditionally high alcohol consumption level.15

This study aimed at evaluating what proportion of pregnant women received health advice on alcohol consumption during pregnancy by the obstetricians, midwives and general practitioners (GPs) involved, according to the recent memory of the pregnant women. A second aim was to identify what message, in this regard, they remember having received. Finally, the third aim was to analyse whether there is social inequality in receiving health advice on the issue.

In recent decades there has not been a consistent implementation of FASD prevention programmes within the Spanish National Health System. Thus, our first hypothesis in this study was that the majority of pregnant women do not remember having received health advice regarding alcohol consumption in pregnancy. The second hypothesis was that even in cases where this information is conveyed, a clear message recommending no consumption of alcohol during pregnancy is not always perceived. The third hypothesis was that educational level could be a key factor in the actual accessibility to health advice on the issue.

MethodSetting and study designA cross-sectional descriptive study was performed with a representative sample of pregnant women receiving care in the outpatient clinics of a university hospital in a southern Spanish city (Seville). The data were collected through face-to-face structured interviews carried out by trained health professionals, using a customised questionnaire.

The population in the geographical area served by this public hospital is quite similar to the average Andalusian population, in terms of the percentage of women in reproductive age (43.1% and 43.6%, respectively), work activity rates among women (49.2% vs. 49.0%), unemployment rates in women (20.8% vs. 18.7%) and educational level (e.g., the percentages of women with only primary school educational level were 23.4% in the area and 24.0% in Andalusia, according to the 2011 population census).

ParticipantsThe target population was pregnant women around their 20th week of pregnancy receiving care in the outpatient clinics of a university hospital during five months in 2016. Inclusion criteria were to be between 19 and 22 weeks of pregnancy, 16 years of age or older, and fluent in written and spoken Spanish. Women participating in this study signed a consent form.

A random sample was obtained, successively choosing one out of every two pregnant women receiving care in these clinics, on their way to the 20th week of gestation ultra-sound. The desired sample size was 400.

Instrument for data collection and variablesThe questionnaire, which was piloted to verify that all questions were comprehensible, sought the following information:

- •

Socio-demographic variables: age, educational level (categorised into five groups: primary school or lower, compulsory secondary school and initial vocational training, post-compulsory secondary school, high vocational training and university studies), employment status (categorised into four groups: full time work, part-time work, unemployed and other situations, as being in temporary disablement or describing oneself as a housewife), home language, country of origin and place of residence.

- •

Obstetric variables: gravidity (including previous miscarriages, induced abortions and the current pregnancy) and pregnancy planning.

- •

Alcohol consumption pattern before pregnancy: using questions of the AUDIT scale,30 patterns of self-reported alcohol consumption before pregnancy were recorded. Subsequently, taking into account the types and amount of alcohol beverages consumed by the interviewee before pregnancy in a usual drinking day, as well as the content of pure alcohol of each type of glass or alcohol container in the city of Seville,31 the grams of alcohol consumed in that typical drinking day were calculated. For abstainers, the computed figure was 0 grams.

- •

Health advice on alcohol consumption during pregnancy: two questions recorded the advice provided in this regard by each of the three types of professionals involved in standardised pregnancy care (midwife, obstetrician and GP), according to the perception and recall of the interviewee.

For midwives (and equally for the two other kinds of professionals), the first question was: “Has your midwife said anything to you about alcohol consumption during pregnancy?”. The answer was dichotomous: “yes” or “no”. If the answer was affirmative, the second question was asked: “Could you please summarise what she said?”. On a card presented to the interviewee, five possible answers were provided, and only one could be chosen: 1) “I can drink whatever alcohol I want, without any problem”; 2) “I can drink a little alcohol every day, without any problem”; 3) “I can drink, as an exception, some alcohol, without any problem”; 4) “I should not drink any alcohol at all”; 5) “Other (please specify)”.

FieldworkData collection was carried out during the spring and summer of 2016. The interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained healthcare professionals, in a private space prepared in the outpatient clinic of the hospital.

Data analysisA univariate analysis was carried out for each variable, followed by the generation of three new variables: number of health professionals providing advice on alcohol consumption in pregnancy (always according to the perception and recall of the interviewees), grams of alcohol consumed in a usual dinking day before pregnancy and the categorization of the perceived advice provided by each health professional (correct advice, incorrect advice, no advice).

Subsequently, a bivariate analysis of the interrelationship between the variables relating to the health advice on alcohol consumption during pregnancy and each of the socio-demographic variables that could indicate social inequality (age, education level and employment status) was carried out applying the chi-squared test. Standardised residuals were calculated for each cell of the resulting contingency tables. Similarly, associations between perceived health advice on this issue and obstetrics variables were explored, as well as with alcohol consumption before pregnancy. Finally, a multiple regression was carried out by placing the number of health professionals providing advice as dependent variable and considering educational level, employment status, pregnancy planning and grams of alcohol consumed in a typical drinking day before pregnancy as independent variables.

EthicsThe study protocol was approved by the Ethics Coordinating Committee of Biomedical Research in Andalusia. After having provided written and oral information on the study's purpose, all participants gave their informed consent. The data were anonymously handled. The Helsinki declaration of 1975 and its subsequent amendments were respected.

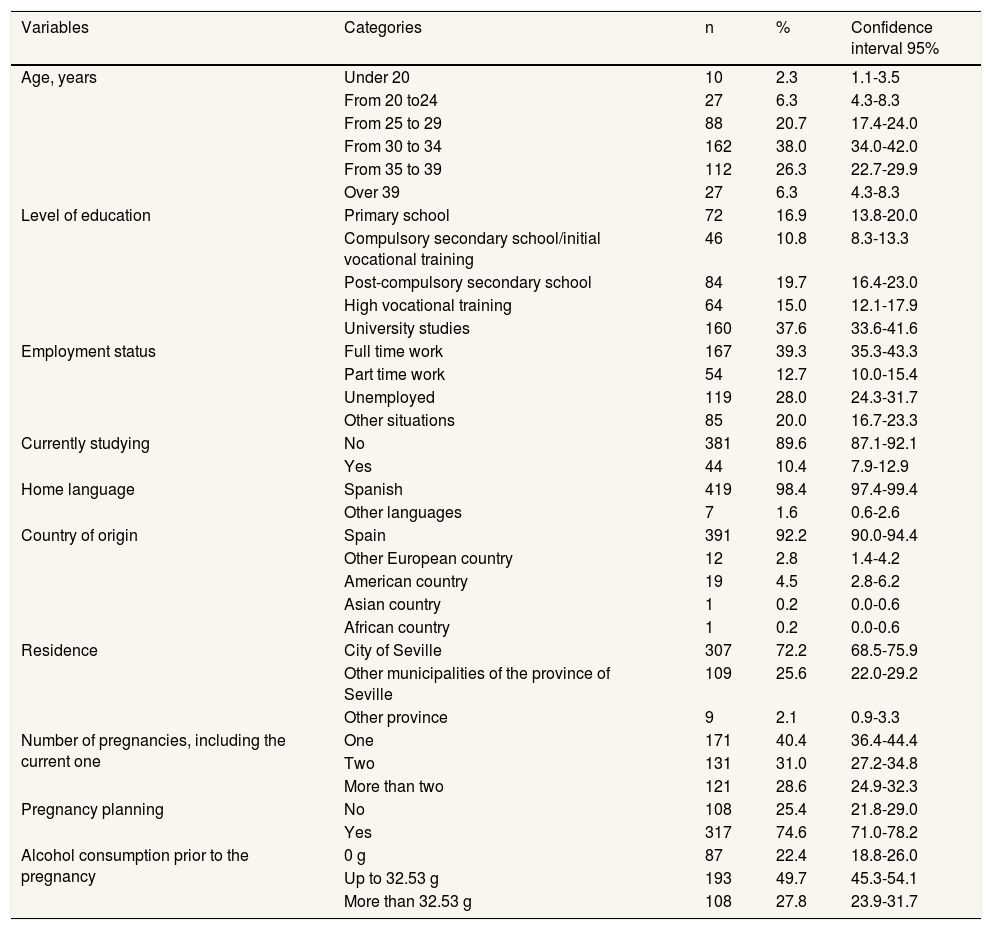

ResultsOut of a total of 1664 women who received care in these outpatient clinics throughout the five months, half of them (832) were asked to participate in the study, and 426 agreed to participate (51.2%), 92.2% born in Spain. The mean age of the interviewees was 31.9 years of age (standard deviation: 5.3). The socio-demographic description of the resulting sample is displayed in Table 1.

Description of the sample according to socio-demographic characteristics, obstetric history and alcohol consumption prior to the pregnancy.

| Variables | Categories | n | % | Confidence interval 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | Under 20 | 10 | 2.3 | 1.1-3.5 |

| From 20 to24 | 27 | 6.3 | 4.3-8.3 | |

| From 25 to 29 | 88 | 20.7 | 17.4-24.0 | |

| From 30 to 34 | 162 | 38.0 | 34.0-42.0 | |

| From 35 to 39 | 112 | 26.3 | 22.7-29.9 | |

| Over 39 | 27 | 6.3 | 4.3-8.3 | |

| Level of education | Primary school | 72 | 16.9 | 13.8-20.0 |

| Compulsory secondary school/initial vocational training | 46 | 10.8 | 8.3-13.3 | |

| Post-compulsory secondary school | 84 | 19.7 | 16.4-23.0 | |

| High vocational training | 64 | 15.0 | 12.1-17.9 | |

| University studies | 160 | 37.6 | 33.6-41.6 | |

| Employment status | Full time work | 167 | 39.3 | 35.3-43.3 |

| Part time work | 54 | 12.7 | 10.0-15.4 | |

| Unemployed | 119 | 28.0 | 24.3-31.7 | |

| Other situations | 85 | 20.0 | 16.7-23.3 | |

| Currently studying | No | 381 | 89.6 | 87.1-92.1 |

| Yes | 44 | 10.4 | 7.9-12.9 | |

| Home language | Spanish | 419 | 98.4 | 97.4-99.4 |

| Other languages | 7 | 1.6 | 0.6-2.6 | |

| Country of origin | Spain | 391 | 92.2 | 90.0-94.4 |

| Other European country | 12 | 2.8 | 1.4-4.2 | |

| American country | 19 | 4.5 | 2.8-6.2 | |

| Asian country | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0-0.6 | |

| African country | 1 | 0.2 | 0.0-0.6 | |

| Residence | City of Seville | 307 | 72.2 | 68.5-75.9 |

| Other municipalities of the province of Seville | 109 | 25.6 | 22.0-29.2 | |

| Other province | 9 | 2.1 | 0.9-3.3 | |

| Number of pregnancies, including the current one | One | 171 | 40.4 | 36.4-44.4 |

| Two | 131 | 31.0 | 27.2-34.8 | |

| More than two | 121 | 28.6 | 24.9-32.3 | |

| Pregnancy planning | No | 108 | 25.4 | 21.8-29.0 |

| Yes | 317 | 74.6 | 71.0-78.2 | |

| Alcohol consumption prior to the pregnancy | 0 g | 87 | 22.4 | 18.8-26.0 |

| Up to 32.53 g | 193 | 49.7 | 45.3-54.1 | |

| More than 32.53 g | 108 | 27.8 | 23.9-31.7 |

A quarter of the interviewees did not plan the current pregnancy (25.4%; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 21.8-29.0%) and 40.4% were in their first pregnancy (95%CI: 36.4-44.4%). Regarding alcohol consumption before pregnancy, 22.4% of interviewees self-reported being abstainers (95%CI: 18.8-26.0%); the rest reported an average consumption of 32.53 grams of alcohol in a typical drinking day (Table 1).

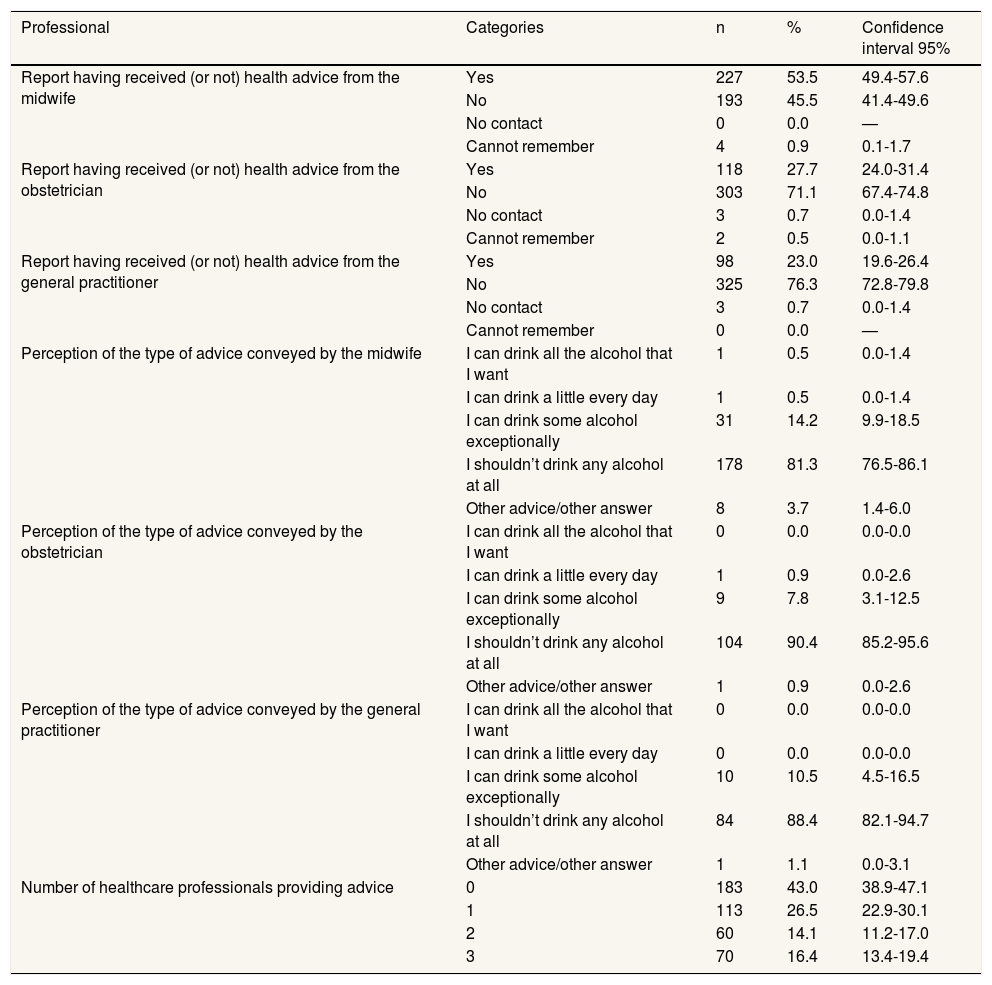

Approximately half of the sample reported having received some health advice on alcohol consumption from the midwife (53.5%) and a quarter from the obstetrician (27.7%) or the GP (23%). A significant segment of the sample (43%) reported having received no advice on alcohol consumption from any of the three types of professionals studied. Only 30.5% of the interviewees reported having been advised on this topic by more than one of the three types of professionals (the respective 95%IC are displayed in Table 2).

Pregnant women's perception of the health advice received from health professionals about alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

| Professional | Categories | n | % | Confidence interval 95% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Report having received (or not) health advice from the midwife | Yes | 227 | 53.5 | 49.4-57.6 |

| No | 193 | 45.5 | 41.4-49.6 | |

| No contact | 0 | 0.0 | — | |

| Cannot remember | 4 | 0.9 | 0.1-1.7 | |

| Report having received (or not) health advice from the obstetrician | Yes | 118 | 27.7 | 24.0-31.4 |

| No | 303 | 71.1 | 67.4-74.8 | |

| No contact | 3 | 0.7 | 0.0-1.4 | |

| Cannot remember | 2 | 0.5 | 0.0-1.1 | |

| Report having received (or not) health advice from the general practitioner | Yes | 98 | 23.0 | 19.6-26.4 |

| No | 325 | 76.3 | 72.8-79.8 | |

| No contact | 3 | 0.7 | 0.0-1.4 | |

| Cannot remember | 0 | 0.0 | — | |

| Perception of the type of advice conveyed by the midwife | I can drink all the alcohol that I want | 1 | 0.5 | 0.0-1.4 |

| I can drink a little every day | 1 | 0.5 | 0.0-1.4 | |

| I can drink some alcohol exceptionally | 31 | 14.2 | 9.9-18.5 | |

| I shouldn’t drink any alcohol at all | 178 | 81.3 | 76.5-86.1 | |

| Other advice/other answer | 8 | 3.7 | 1.4-6.0 | |

| Perception of the type of advice conveyed by the obstetrician | I can drink all the alcohol that I want | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0-0.0 |

| I can drink a little every day | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0-2.6 | |

| I can drink some alcohol exceptionally | 9 | 7.8 | 3.1-12.5 | |

| I shouldn’t drink any alcohol at all | 104 | 90.4 | 85.2-95.6 | |

| Other advice/other answer | 1 | 0.9 | 0.0-2.6 | |

| Perception of the type of advice conveyed by the general practitioner | I can drink all the alcohol that I want | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0-0.0 |

| I can drink a little every day | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0-0.0 | |

| I can drink some alcohol exceptionally | 10 | 10.5 | 4.5-16.5 | |

| I shouldn’t drink any alcohol at all | 84 | 88.4 | 82.1-94.7 | |

| Other advice/other answer | 1 | 1.1 | 0.0-3.1 | |

| Number of healthcare professionals providing advice | 0 | 183 | 43.0 | 38.9-47.1 |

| 1 | 113 | 26.5 | 22.9-30.1 | |

| 2 | 60 | 14.1 | 11.2-17.0 | |

| 3 | 70 | 16.4 | 13.4-19.4 |

Within the segment of pregnant women who said that they had been informed with regard to alcohol consumption during pregnancy, the message perceived by the majority was that “I should not drink any alcohol at all”. Specifically, 81.3% of pregnant women advised by their midwife reported having received this message, as well as 90.4% of those informed by their obstetrician and 88.4% of those who received advice from their GP. By contrast, other pregnant women stated that the advice given was that they could, exceptionally, drink some alcohol without there being any problem with their pregnancy. This was the case of 14.2% of the women regarding their midwife, 7.8% for their obstetrician and 10.5% for their GP. A few cases reported having received other advice (see Table 2 for details).

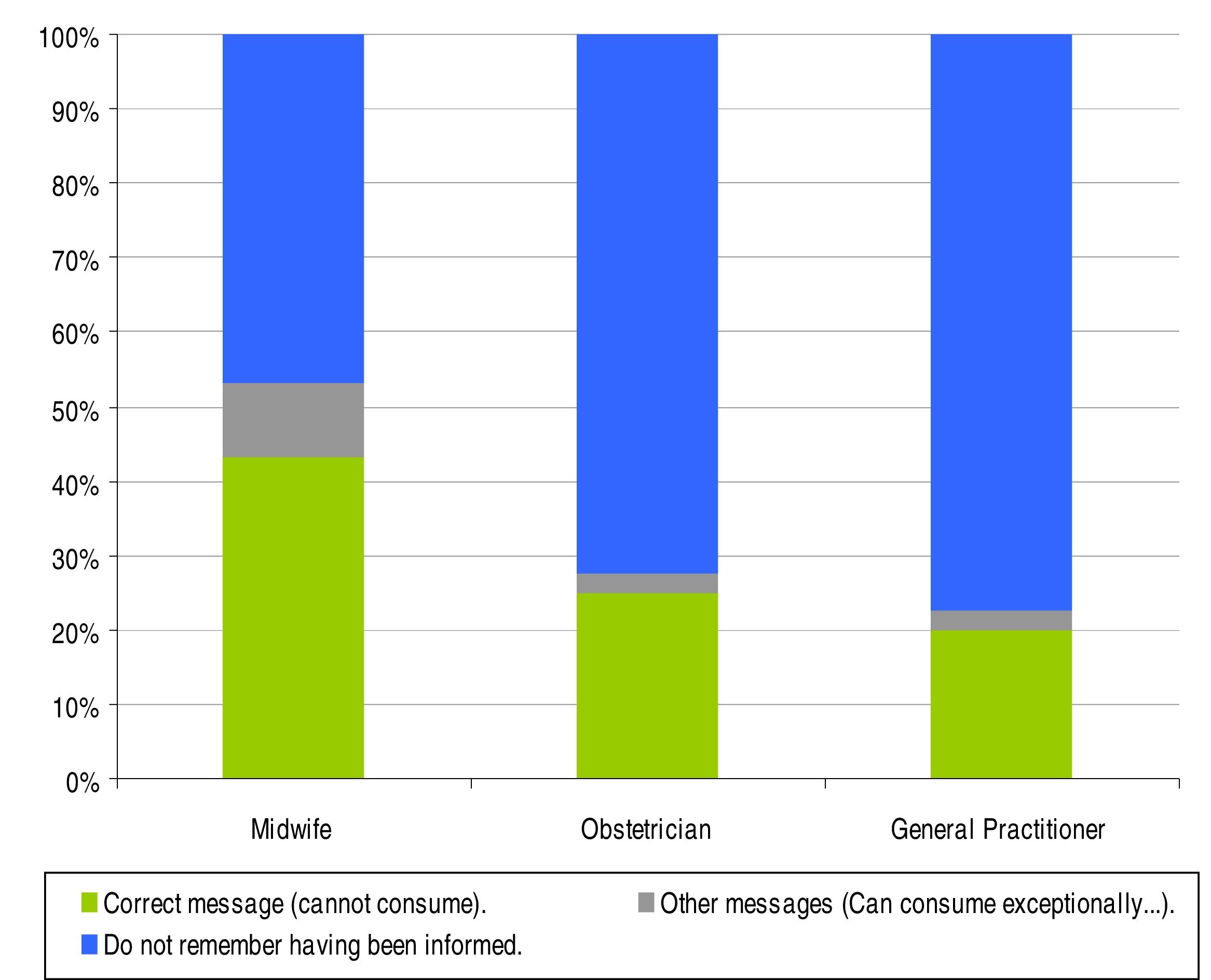

Combining both variables (having received or not having received health advice on the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy and the message perceived if informed), it can be estimated, according to the recall of the interviewees, that 43.5% of the total pregnant women in the sample remembered having received the correct message (not to consume any alcohol at all during pregnancy) from their midwife, 25% from their obstetrician and 20.3% from their GP (Fig. 1).

Heterogeneity was analysed amongst the interviewees’ answers regarding health advice on alcohol consumption during pregnancy in accordance with the pregnant woman's age, educational level, employment status, number of pregnancies, pregnancy planning and reported alcohol consumption before pregnancy. No major differences were detected regarding age.

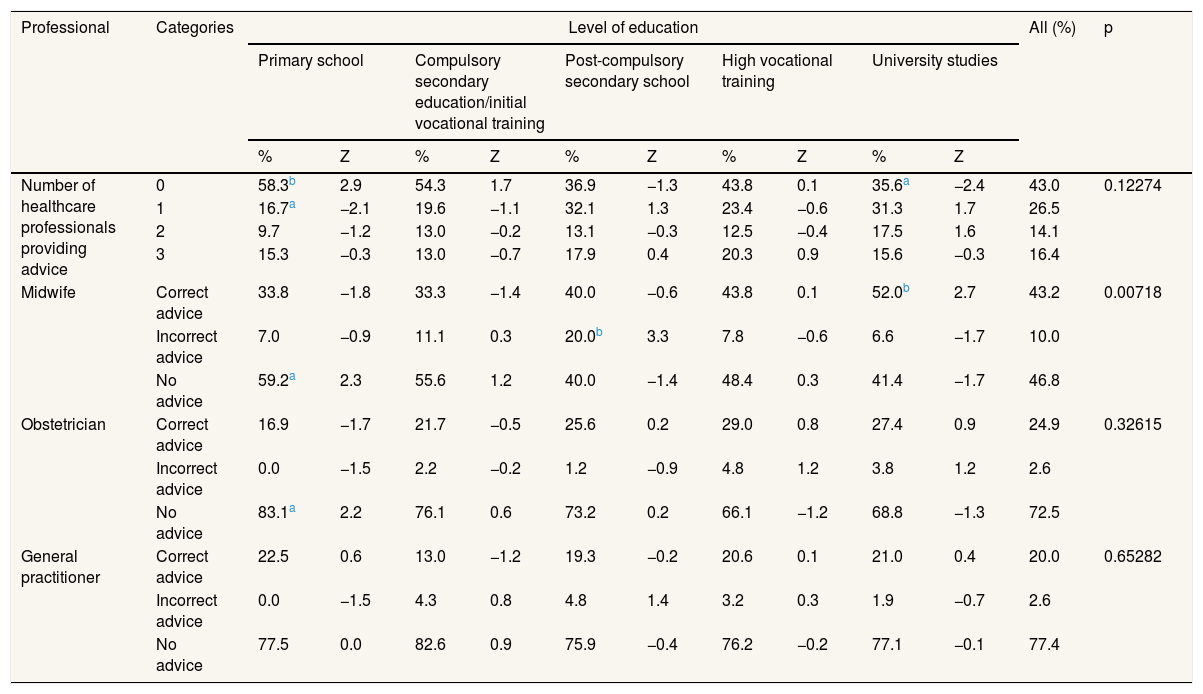

Women with only primary education stood out in terms of the high proportion of them who stated that they had not been informed by any of the three types of health professionals (58.3%; z=2.9; p <0.01). The opposite was the case for women with higher (university) education, of whom 35.6% reported not having received any advice from any of the three studied sources on this subject (Table 3).

Pregnant women's perception of the health advice received from health professionals about alcohol consumption during pregnancy, by level of education and the type of health care professional.

| Professional | Categories | Level of education | All (%) | p | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary school | Compulsory secondary education/initial vocational training | Post-compulsory secondary school | High vocational training | University studies | |||||||||

| % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | ||||

| Number of healthcare professionals providing advice | 0 | 58.3b | 2.9 | 54.3 | 1.7 | 36.9 | −1.3 | 43.8 | 0.1 | 35.6a | −2.4 | 43.0 | 0.12274 |

| 1 | 16.7a | −2.1 | 19.6 | −1.1 | 32.1 | 1.3 | 23.4 | −0.6 | 31.3 | 1.7 | 26.5 | ||

| 2 | 9.7 | −1.2 | 13.0 | −0.2 | 13.1 | −0.3 | 12.5 | −0.4 | 17.5 | 1.6 | 14.1 | ||

| 3 | 15.3 | −0.3 | 13.0 | −0.7 | 17.9 | 0.4 | 20.3 | 0.9 | 15.6 | −0.3 | 16.4 | ||

| Midwife | Correct advice | 33.8 | −1.8 | 33.3 | −1.4 | 40.0 | −0.6 | 43.8 | 0.1 | 52.0b | 2.7 | 43.2 | 0.00718 |

| Incorrect advice | 7.0 | −0.9 | 11.1 | 0.3 | 20.0b | 3.3 | 7.8 | −0.6 | 6.6 | −1.7 | 10.0 | ||

| No advice | 59.2a | 2.3 | 55.6 | 1.2 | 40.0 | −1.4 | 48.4 | 0.3 | 41.4 | −1.7 | 46.8 | ||

| Obstetrician | Correct advice | 16.9 | −1.7 | 21.7 | −0.5 | 25.6 | 0.2 | 29.0 | 0.8 | 27.4 | 0.9 | 24.9 | 0.32615 |

| Incorrect advice | 0.0 | −1.5 | 2.2 | −0.2 | 1.2 | −0.9 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 2.6 | ||

| No advice | 83.1a | 2.2 | 76.1 | 0.6 | 73.2 | 0.2 | 66.1 | −1.2 | 68.8 | −1.3 | 72.5 | ||

| General practitioner | Correct advice | 22.5 | 0.6 | 13.0 | −1.2 | 19.3 | −0.2 | 20.6 | 0.1 | 21.0 | 0.4 | 20.0 | 0.65282 |

| Incorrect advice | 0.0 | −1.5 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 4.8 | 1.4 | 3.2 | 0.3 | 1.9 | −0.7 | 2.6 | ||

| No advice | 77.5 | 0.0 | 82.6 | 0.9 | 75.9 | −0.4 | 76.2 | −0.2 | 77.1 | −0.1 | 77.4 | ||

All differences tested with χ2 test categorical variables.

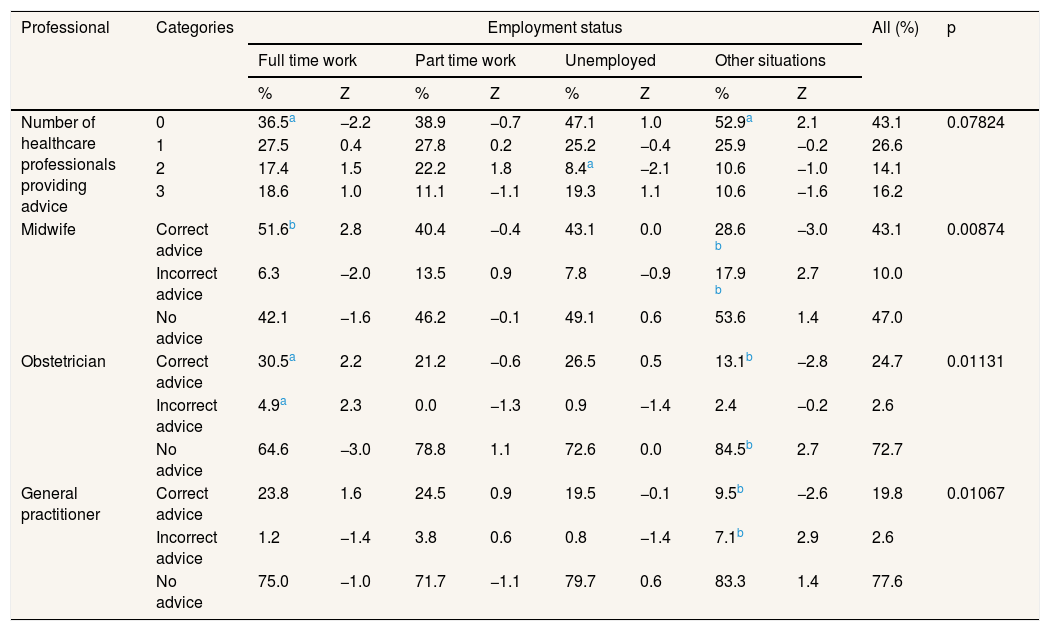

Pregnant women with full-time jobs were the ones who, to a lesser extent, stated that they had not received information on the subject from any of the three types of health professionals (36.5%; z=−2.2; p <0.05); that is, they were the ones who, as a whole, were the most informed by at least one of the three sources. In turn, more than half of the women (52.9%) who fell in the category “other work situations” reported that they had not been informed by any of the three types of sources (z=2.1; p<0.05) (Table 4). A small percentage of unemployed women declared that they had received advice on the matter by two health professionals (8.4%; z=−2.1; p <0.05).

Pregnant women's perception of the health advice received from health professionals about alcohol consumption during pregnancy, by employment status and the type of health care professional.

| Professional | Categories | Employment status | All (%) | p | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full time work | Part time work | Unemployed | Other situations | ||||||||

| % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | ||||

| Number of healthcare professionals providing advice | 0 | 36.5a | −2.2 | 38.9 | −0.7 | 47.1 | 1.0 | 52.9a | 2.1 | 43.1 | 0.07824 |

| 1 | 27.5 | 0.4 | 27.8 | 0.2 | 25.2 | −0.4 | 25.9 | −0.2 | 26.6 | ||

| 2 | 17.4 | 1.5 | 22.2 | 1.8 | 8.4a | −2.1 | 10.6 | −1.0 | 14.1 | ||

| 3 | 18.6 | 1.0 | 11.1 | −1.1 | 19.3 | 1.1 | 10.6 | −1.6 | 16.2 | ||

| Midwife | Correct advice | 51.6b | 2.8 | 40.4 | −0.4 | 43.1 | 0.0 | 28.6 b | −3.0 | 43.1 | 0.00874 |

| Incorrect advice | 6.3 | −2.0 | 13.5 | 0.9 | 7.8 | −0.9 | 17.9 b | 2.7 | 10.0 | ||

| No advice | 42.1 | −1.6 | 46.2 | −0.1 | 49.1 | 0.6 | 53.6 | 1.4 | 47.0 | ||

| Obstetrician | Correct advice | 30.5a | 2.2 | 21.2 | −0.6 | 26.5 | 0.5 | 13.1b | −2.8 | 24.7 | 0.01131 |

| Incorrect advice | 4.9a | 2.3 | 0.0 | −1.3 | 0.9 | −1.4 | 2.4 | −0.2 | 2.6 | ||

| No advice | 64.6 | −3.0 | 78.8 | 1.1 | 72.6 | 0.0 | 84.5b | 2.7 | 72.7 | ||

| General practitioner | Correct advice | 23.8 | 1.6 | 24.5 | 0.9 | 19.5 | −0.1 | 9.5b | −2.6 | 19.8 | 0.01067 |

| Incorrect advice | 1.2 | −1.4 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 0.8 | −1.4 | 7.1b | 2.9 | 2.6 | ||

| No advice | 75.0 | −1.0 | 71.7 | −1.1 | 79.7 | 0.6 | 83.3 | 1.4 | 77.6 | ||

All differences tested with χ2 test categorical variables.

The percentage of pregnant women who reported having been informed by the three health sources was particularly high (21.6%; z=2.4; p <0.05) among those who were pregnant for the first time.

No major differences were detected regarding the number of health professionals providing advice on the issue in accordance with pregnancy planning or reported alcohol consumption before pregnancy (data not displayed in tables).

Women with only primary education were the ones who in greater proportion stated that they had not received any advice on alcohol consumption during pregnancy, either from the midwife (59.2%; z=2.3; p <0.05) or from the obstetrician (83.1%; z=2,2; p <0.05). With regard to the GP, there were no significant differences in this regard according to the level of education (Table 3).

With respect to employment situation, women who worked full-time were the ones who to a lesser extent stated that they had not received health advice on the use of alcohol in pregnancy by the obstetrician (64.6%; z=−3.0; p <0.01). Those that were found in “other work situations” were, in turn, the ones that made this statement in the greatest proportion (84.5%; z=2.7; p <0.01). No significant differences were noted in this respect regarding midwives or GPs (Table 4).

Pregnant women with university studies were the ones who reported having received the correct message —not to drink any alcohol during the pregnancy— in a higher percentage by the midwife (52%; z=2.7; p <0.01). In turn, pregnant women with post-compulsory secondary education were those who in greater proportion reported having received different advice (20%; z=3.3; p <0.01). As to obstetricians and GPs, there were no relevant differences in this regard depending on the educational level of the pregnant women (Table 3). The full-time working pregnant women were the ones who in greater proportion reported that the midwife recommended that they not drink any alcohol during the pregnancy (51.6%; z=2.8; p <0.01); this response was particularly rare among the women in other employment situations (28.6%; z=−3.0; p <0.01). The latter applies to the advice of the GP (9.5%; z=−2.6; p <0.01) and the obstetrician (13.1%; z=−2.8; p <0.01) as well (Table 4).

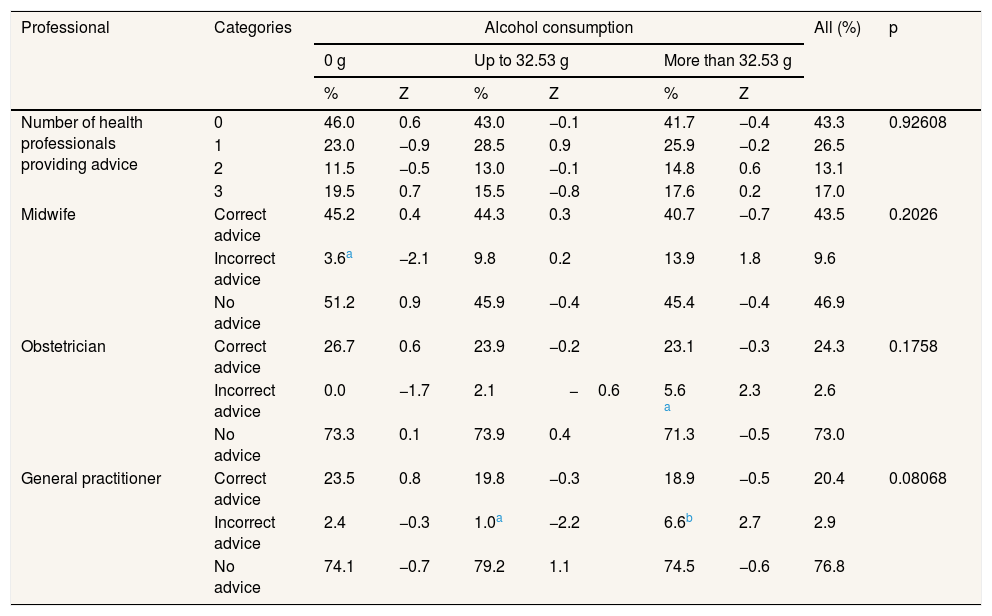

Regarding alcohol consumption before pregnancy, women who declared that they had been abstainers before their pregnancy were the ones who to a lesser degree remembered having received advice from the midwife other than abstaining from consuming any alcoholic beverages during pregnancy (3.6%; z=−2.1; p <0.05). In turn, pregnant women who before pregnancy consumed more grams of alcohol were those who, among the group that remembered having received advice, indicate that this advice from the obstetrician (5.6%; z=2.3; p ≤0.05) or from the GP (6.6%; z=2.7; p <0.01) did not include that they should drink no alcohol during pregnancy. On the other hand, among the women who consumed below-average amounts of alcohol before pregnancy, only a very small percentage (1%; z=−2.2; p <0.05) recalled having received advice from the GP other than the correct advice (Table 5).

Pregnant women's perception of the health advice received from health professionals about alcohol consumption during pregnancy, according to alcohol consumption before pregnancy on a typical drinking day.

| Professional | Categories | Alcohol consumption | All (%) | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 g | Up to 32.53 g | More than 32.53 g | |||||||

| % | Z | % | Z | % | Z | ||||

| Number of health professionals providing advice | 0 | 46.0 | 0.6 | 43.0 | −0.1 | 41.7 | −0.4 | 43.3 | 0.92608 |

| 1 | 23.0 | −0.9 | 28.5 | 0.9 | 25.9 | −0.2 | 26.5 | ||

| 2 | 11.5 | −0.5 | 13.0 | −0.1 | 14.8 | 0.6 | 13.1 | ||

| 3 | 19.5 | 0.7 | 15.5 | −0.8 | 17.6 | 0.2 | 17.0 | ||

| Midwife | Correct advice | 45.2 | 0.4 | 44.3 | 0.3 | 40.7 | −0.7 | 43.5 | 0.2026 |

| Incorrect advice | 3.6a | −2.1 | 9.8 | 0.2 | 13.9 | 1.8 | 9.6 | ||

| No advice | 51.2 | 0.9 | 45.9 | −0.4 | 45.4 | −0.4 | 46.9 | ||

| Obstetrician | Correct advice | 26.7 | 0.6 | 23.9 | −0.2 | 23.1 | −0.3 | 24.3 | 0.1758 |

| Incorrect advice | 0.0 | −1.7 | 2.1 | −0.6 | 5.6 a | 2.3 | 2.6 | ||

| No advice | 73.3 | 0.1 | 73.9 | 0.4 | 71.3 | −0.5 | 73.0 | ||

| General practitioner | Correct advice | 23.5 | 0.8 | 19.8 | −0.3 | 18.9 | −0.5 | 20.4 | 0.08068 |

| Incorrect advice | 2.4 | −0.3 | 1.0a | −2.2 | 6.6b | 2.7 | 2.9 | ||

| No advice | 74.1 | −0.7 | 79.2 | 1.1 | 74.5 | −0.6 | 76.8 | ||

All differences tested with χ2 test categorical variables.

Prior to the multiple regression, an analysis of the correlations among the variables in play (number of health professionals that give advice, educational level, employment situation, number of pregnancies, pregnancy planning, and alcohol consumption before the pregnancy) was carried out. No significant effect sizes were detected (none of the correlations reached the value of 0.3). Regarding the number of health professionals that gave advice, a negative correlation was found with regard to the number of pregnancies; that is, the more pregnancies a woman had had, the less she remembered receiving advice on the subject (−0.159; p <0.01). With respect to educational level, a positive correlation was detected: women with higher levels of education remembered to a higher degree having received information from the health professionals that attended them (0.104; p <0.05). Lastly, the multiple regression (after excluding the employment situation, given that it does not present a clearly ordinal sequence in its categories) only showed a relation with regard to the number of pregnancies, which is inversely proportional to the number of professionals informing on the subject (β:−0.172; p <0.01).

DiscussionThe aim of this study was to analyse whether pregnant women remembered having received advice related to alcohol consumption during pregnancy from healthcare professionals providing care to them, to identify the messages perceived and to analyse if there was any social inequality in the accessibility of this information.

Although in this study the actual practices of health professionals in this area have not been investigated —the information was retrieved from the perception and memory of the pregnant women— the results suggest that giving health advice related to alcohol consumption during pregnancy is not a widespread practice among the health professionals who provide healthcare to them. It is remarkable that 43% of the interviewees stated that they had not received any health advice at all regarding this matter, while only 30.5% remembered having been informed on this crucial subject by more than one source.

Social differences can also be detected —fundamentally according to educational level— in the recall of having received some advice on this matter. Women with lower educational levels (only primary education) are precisely those who remembered having been advised by the midwife or the obstetrician in this regard to a lesser extent.

Overall, only a minority of pregnant women remembered having received the correct advice (to avoid any alcohol consumption during pregnancy) from the professionals that provide healthcare to them (specifically, 43.5% regarding the midwife, 25% with regard to the obstetrician and 20.3% regarding the GP).

Social differences are also detected in terms of the content of the remembered message. Women with university studies, as well as those who work full time, stood out in terms of stating that the midwife had advised them not to drink any alcohol. In other words, the presumably most educated and generally better informed women were those who to a higher degree had received (or retained) the right advice on this matter from their midwife. In contrast, women that fell under the category “other employment situations” stood out for being those who in greater percentage remembered having received from the midwife a message different from the correct one.

The social inequality that is observed both in the statement of having or not received some type of health advice on the subject, as well as in the specific content of the message that is remembered, lends itself to different interpretations. On the one hand, it may reflect individual differences, related to educational level, in the capacity for remembering advice provided by healthcare professionals. It may also be that the most educated women (or those who are in better employment situations) are more proactive when it comes to gathering information in the healthcare provider's office. It is also possible that in certain aspects of the relationship between the providers and the pregnant women there may be a differential treatment, depending on the cultural level of the latter. Socio-economic barriers in provider-patient communication have been detected regarding other issues, such as physical activity or nutrition counselling during pregnancy.32 All these findings suggest the need of increasing providers’ awareness of socio-economic disparities in communication with users.

In any case, one should not forget that, from a preventive perspective, the truly important message is the one that users remember having received, even if it does not coincide with the one given by the provider, because it can influence the pregnant women's behavior. Therefore, the low proportion of pregnant women who remember having received the correct message is particularly worrisome, since it points to a prominent preventable cause of congenital anomalies.

The results of this study are similar to those of research carried out in some other countries, like Denmark. In 2009, only 53% of GPs working in the Antenatal Care Centre in Aarhus (Denmark) recommended not consuming any alcohol during pregnancy.33 In turn, midwives of the same center (n=54) in general knew the official recommendation about alcohol consumption during pregnancy (abstention), yet only 61% informed pregnant women accordingly.23

In studies of professional practices related to the prevention, diagnosis and management of cases of FASD, it has been noted that broad professional sectors are calling for tools to carry out their work in this field more easily and recognise the difficulties involved in discussing this subject with users.24 They request training in communication skills, which will allow them to guide and motivate pregnant women or women of childbearing age effectively.20,25,34,35

On the other hand, it is striking that the number of pregnancies is inversely proportional to the number of professionals informing on the subject, according to the retrieved data. This could reflect, among other factors, a greater receptivity of women who are in their first pregnancy toward health related advice, or a greater educational effort from healthcare professionals toward these women.

It has also been noted that alcohol consumption prior to the pregnancy introduces some modifications regarding the pregnant women's statements, both in terms of whether or not they remembered having been guided on alcohol consumption during pregnancy and the specific content of the remembered message. If the women who report that they did not consume alcohol before their pregnancy are those who to a greater extent claim to have received advice from the midwife on this matter, and those who consumed the most are the ones who to a larger extent remember having received a different message than to avoid all alcohol consumption, this may reflect both an attitudinal bias in the memory of the women and differential health practices depending on the user's alcohol consumption pattern prior to the pregnancy. From the data collected in this study, it cannot be determined whether the first or the second is more likely, but, in any case, it would be paradoxical that midwives made a greater preventive effort towards the women who claimed to be abstainers before their pregnancy.

The study results suggest that the healthcare system must urgently make an institutional effort to ensure that all healthcare professionals who provide preconception care or care to women who are already pregnant receive training in this field, with the aim of enabling them to carry out their role in the prevention of FASD. This implies receiving the necessary training to be able to assess alcohol consumption patterns effectively and efficiently among pregnant women (or women of childbearing age). It also involves receiving training in ideal communication strategies related to this and other aspects of the user's lifestyle. As with other aspects of perinatal care, low-risk women should receive brief advice, those classified as moderate risk should receive a brief intervention, whereas those who are high risk need referral to specialty care.36

The situation reported in this study highlights the need for adopting suitable plans for continued training of healthcare professionals in this field, as well as for verifying whether future healthcare professionals are receiving proper training in this area. Other professional sectors, such as social services personnel, the staff of school guidance departments and of early childhood intervention centers, should also receive information about FASD. The impact of FASD training on professional practice has already been shown in countries such as the United States and Sweden.24,37

The WHO European Action Plan to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol (2012-2020) establishes, amongst other measures, the relevance of interventions carried out by the healthcare provider with pregnant women. In this regard, the clinical practice protocols in pregnancy care should include, in all countries, the evaluation of alcohol consumption in pregnant women, and it should provide information about the risks involved and, whenever necessary, the supplementary support they may need to achieve avoidance.

In addition, since prenatal alcohol exposure can be teratogenic from the start of pregnancy and a relevant proportion of pregnancies are unplanned, women of a childbearing age must be advised about the risks of consuming alcohol while pregnant before they get pregnant.27

Strengths and limitations of the studyThis study explores the present status of health preventive practice in relation to a key issue in the prevention of congenital defects that has been scarcely studied. The sample was chosen at random from pregnant women receiving care in outpatient clinics of their hospital (a public university hospital), all approximately in the 20th week of pregnancy. Sociologically, the sample is heterogeneous and reflects the social diversity of the population served in the community health area. The feminine population of the geographical area served by the hospital is quite similar to the average Andalusian feminine population. The interviews were carried out face-to-face by trained healthcare professionals, in a private space prepared in the hospital's outpatient clinic, ensuring preservation of anonymity. The interviewees were asked for recent retrospective data. The rates of omission in the responses were 0% or close to 0% (depending on the question). All of the above represent the strengths of the study.

However, it also has its limitations. It is a descriptive study with a cross-sectional design, which prevented us from identifying causal relations between the variables studied. The sample did not include foreigners who did not speak Spanish, since interpreters were unavailable. The socio-demographic characteristics of the women who declined to participate in the study were not recorded. The data were declared by the women themselves, without actually verifying the information given by the healthcare professionals.

Conclusions- •

According to the recall of pregnant women, only approximately half of the midwives and a quarter of the obstetricians and the GPs gave them some type of information (not always correct) about alcohol consumption during pregnancy.

- •

43% of the interviewees stated that they had not received any health advice regarding this matter.

- •

Only 43.5% of the sample remembered having received the correct message (not to consume any alcohol at all during pregnancy) from their midwife, 25% from their obstetrician and 20.3% from their GP.

- •

Women with a low educational level were those who to the least extent declared having received health advice on the issue.

Carlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Prenatal alcohol exposure can cause permanent brain damage and is usually accompanied by abnormal facial features and congenital deformities, all with lifelong consequences. It can be prevented by avoiding alcohol consumption throughout pregnancy.

What does this study add to the literature?Only a minority of pregnant women cared for in a community health area of Seville (Spain) remembered having received the correct advice (not to consume any alcohol at all during pregnancy) from health care practitioners. Women with a low educational level were those who to the least extent declared having received health advice on the issue.

The corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsR. Mendoza, I. Corrales, E. Morales-Marente, M.S. Palacios and C. Rodríguez-Reinado conceived and designed the study, advised by O. García-Algar. I. Corrales and R. Mendoza coordinated the data collection. E. Morales-Marente was responsible for the data analysis. All authors interpreted the results, drafted, reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

Preliminary versions of this paper were presented in the Social Epidemiology Seminar of the Carlos III Health Institute (Madrid, May 2016) and in the XXXIV Scientific Meeting of the Spanish Epidemiology Society-XI Congress of the Portuguese Epidemiology Association (Seville, September 2016).

AcknowledgementsThe authors acknowledge Diego Gómez-Baya (University of Huelva), Fátima Larios (University of Sevilla) and Rocío Medero (Hospital N.S. Valme, Andalusian Health Service) for their contributions to the design and development of this study as research team members.

FundingThe study has been funded by the Research Group on Health Promotion and Development of Lifestyle across the Life Span (University of Huelva, Spain), with funding received from the Scientific Policy Strategy of the University of Huelva and the Andalusian Plan for Research, Development and Innovation (PAIDI).

Conflicts of interestNone.