To analyze the evolution of hypnosedative use in the Spanish population aged 15 to 64 (2005-2022), identifying regional variations and changes in users profile.

MethodWe used data from the Survey on the Use of Alcohol and other Drugs in Spain. Past 30-day use was analyzed by sex, age and autonomous community between 2005 and 2022. A multivariate logistic regression was used to identify characteristics of consumption; the temporal trend of prevalence and adjusted odds ratio were evaluated using joinpoint regression models.

ResultsBetween 2005 and 2022, the prevalence of hypnosedative use in Spain increased (from 3.7% to 9.7%) with an annual percentage change of 4.7%. The maximum increase was observed among women aged 55 to 64, reaching a prevalence of 21.4% in 2022. Use increased in all autonomous communities, with Cantabria, La Rioja and Andalusia standing out. The likelihood of using hypnosedatives was higher among women, the oldest age groups, those with basic or intermediate education, those unemployed or economically inactive, those not living with a partner or family, Spanish citizens, and tobacco or cannabis users.

ConclusionsAn upward trend in the use of hypnosedatives in Spain has been observed since 2005, with variations according to sex, age, and autonomous community. It is crucial to update regional addiction plans, promote preventive strategies and foster collaboration between health authorities, medical professionals and the population to address mental health inequalities and ensure adequate care and responsible prescribing.

Analizar la evolución del consumo de hipnosedantes en la población española de 15 a 64 años desde 2005 hasta 2022, identificando variaciones regionales y cambios en el perfil de los consumidores.

MétodoSe utilizaron datos de la Encuesta sobre Uso de Alcohol y otras Drogas en España. Se analizó el consumo en los últimos 30 días, desglosado por sexo, edad y comunidad autónoma entre 2005 y 2022. Se realizó una regresión logística multivariante para identificar las características asociadas al consumo y se evaluó la tendencia temporal de las prevalencias y las odds ratio ajustadas utilizando modelos de regresión joinpoint.

ResultadosEntre 2005 y 2022 aumentó la prevalencia de consumo (del 3,7% al 9,7%), con un porcentaje de cambio anual del 4,7%. El mayor incremento se observó en mujeres de 55 a 64 años, alcanzando una prevalencia de 21,4% en 2022. En todas las comunidades autónomas aumentó el consumo, destacando Cantabria, La Rioja y Andalucía. La probabilidad de consumir hipnosedantes fue mayor en las mujeres, en los de mayor edad, con nivel educativo básico o medio, desempleados o inactivos laboralmente, que no conviven con pareja o familia, de nacionalidad española y consumidores de tabaco o cannabis.

ConclusionesEn España se observa un aumento del consumo de hipnosedantes desde 2005, con variaciones por sexo, edad y comunidad autónoma. Es crucial actualizar los planes regionales de adicciones, promover estrategias preventivas y la colaboración entre autoridades sanitarias, profesionales médicos y la población para abordar las desigualdades en salud mental y asegurar una atención adecuada y una prescripción responsable.

A mental disorder, according to the 11th Revision of the International Classification of Diseases, is characterized by a marked change in a person's thinking, emotions or behavior, reflecting problems in mental and biological processes.1 Mental disorders represent a public health challenge due to their increasing prevalence, impact on quality of life, and contribution to the overall burden of morbidity and mortality. In addition, they are a leading cause of years lived with disability, responsible for approximately one in six years lived with disability worldwide.2

The COVID-19 pandemic caused a significant increase in the prevalence of mental disorders worldwide. In 2020, a meta-analysis recorded a 25.6% increase in the prevalence of anxiety and a 27.6% increase in the prevalence of major depression, based on data collected before and during the pandemic.3,4

Patients diagnosed with mental health problems are often prescribed psychotropic drugs (anxiolytics, antidepressants or hypnosedatives).5 In 2019, Spain ranked third globally for psychotropic consumption.6 In addition, hypnotic and anxiolytic use has been increasing in the Spanish population.7 To cite an example, anxiolytic use in the community of Castile and Leon grew by 14.4% between 2015 and 2020.7 According to data from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Health Products, the number of defined daily doses of hypnosedatives per 1000 Spanish inhabitants increased by 20.6% between 2010 and 2021.8

A study by González-López et al.9 in 2022, based on psychiatric prescription data from Andalusia (Spain) revealed a notable increase in psychotropic drug use during the COVID-19 pandemic. When considering gender and age groups, women aged 75 and older experienced the most pronounced rise in medication use.9 The Spanish Alcohol and Other Drug Use Survey 2022 (EDADES) reveals 9.7% of adults aged 15-64 reported using hypnotics or anxiolytics with or without a prescription within the past 30 days, showing a higher prevalence among women (12.1%) compared to men (7.3%).10

Concern about inappropriate hypnotic or anxiolytic use highlights the need for periodic evaluations of prescriptions by health professionals, as well as individual awareness of the negative health effects of prolonged use. These effects include an increased risk of addiction; mortality, when combined with other drugs; suicide attempts; aggressive and antisocial behavior, all with significant impact on social and healthcare costs.11

From a public health point of view, a deeper analysis of the evolution of hypnotic or anxiolytic consumption in Spain is essential, considering the differences between autonomous communities (AC), and variations in consumers profile.

The aim of this study is to describe the temporal evolution of the prevalence of hypnotic or anxiolytic use in the last 30 days with or without prescription in the adult population aged 15 to 64 years in Spain and its AC, and to identify how users characteristics have changed between 2005 and 2022.

MethodData source and sample sizeMicrodata from EDADES, whose main objective is to determine the prevalence and trends in psychoactive substance use and behavioral addictions, were analyzed. EDADES has been performed in Spanish households biennially since 1995 in all AC. It is directed to the general Spanish population, between 15 and 64 years.

The study population is selected by means of a three-stage cluster sampling without substitution. In the first stage, the census tracts are selected; in the second, the households and in the third, one individual per household. The sample is stratified considering the AC, the size of the municipality and the sex and age of the individual.

A trained interviewer collects information in the home through personal interview. A two-section questionnaire is used: one completed by the interviewer and one self-completed by the respondent.

Variables studiedEDADES collects data on drug use over different time periods (ever in life, within the last 12 months, within the last 30 days, and daily in the past 30 days); however, this study only examined responses related to use within the past 30 days. In line with established EDADES nomenclature, the term “hypnosedatives” will be used to refer collectively to anxiolytics and hypnotic-sedative drugs, which are categorized under the N05B and N05C groups of The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.12 Information on hypnosedative consumption is derived from the question: “Have you used tranquilizers, sedatives and/or sleeping pills (drugs to calm nerves or anxiety or sleep medications, such as Lexatin, Orfidal, Noctamid, Trankimazin, Rohypnol, Tranxilium, diazepam, Valium, Stilnox, zolpidem, hypnotics, benzos, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, etc.) in the last 30 days?”. The questions regarding hypnosedative consumption in the last 30 days have changed throughout the different editions of EDADES. In this analysis, a consumer in the last 30 days was considered to be someone who answered at least “1-3 days” or “between 1-3 days” in the case of days of use (2005-2011) or “yes” in the case of use in this time frame (2013-2022), whether the consumption of the hypnosedatives was asked separately for tranquilizers/sedatives and sleeping pills (2005-2013) or together in the same question (2015-2022). A similar question with the added terms “without prescription” and “for non-medical use” derived information on nonprescription hypnosedative use. Those who answered affirmatively to this question are considered nonprescription hypnosedative users. In this study, users of prescription and nonprescription hypnosedatives were combined into a single category: hypnosedative users. Users of valerian, purple passionflower, Dormidine® or melatonin are not included.

To characterize users, the following sociodemographic variables were assessed:

- •

Sex: male or female.

- •

Age group: 15-24 years; 25-34 years; 35-44 years; 45-54 years; and 55-64 years.

- •

Educational level: a) basic: no education, or complete or incomplete primary education; b) intermediate: first or second stage secondary education, and c) high: university studies.

- •

Employment status: a) employed, b) unemployed, and c) inactive (retired, disabled, pensioners, students and those engaged in housework).

- •

Cohabitation with a partner and immediate family members: yes or no.

- •

Country of birth: Spain or other.

- •

Substance use: consumption of tobacco, alcohol and cannabis in the last 30 days assessed independently: yes or no.

The prevalence of hypnosedative use in Spain was estimated overall, by sex and age group, and also by AC for the period 2005-2022. Relative changes by AC were obtained.

To identify the factors associated with consumption in the last 30 days, a bivariate analysis was performed. Afterwards, a multivariate logistic regression model was adjusted by including the variables with a p-value <0.2 of the previous bivariate analysis. The model was adjusted for each year of data and odds ratios (OR) were obtained.

Finally, the trend in the prevalence of hypnosedative use in the last 30 days between 2005 and 2022 was analyzed by sex, age group and AC using joinpoint regression models. These models were also applied on the adjusted OR to identify temporal changes in the characteristics of hypnosedative users. A maximum of three points of change and a significance level of 5% were considered. For each period identified, the annual percentage change (APC) was obtained.

Prevalences, adjusted OR and APC are presented with their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Statistical analysis was performed with the Stata program v17.0, taking into account the sample design. The trend of the prevalences and adjusted OR were analyzed with Joinpoint Regression Program v.9.1.0.

ResultsIn this study, information provided by 205,055 individuals in 2005 (n=27,934), 2007 (n=23,715), 2009 (n=20,109), 2011 (n=22,128), 2013 (n=23,136), 2015 (n=22,541), 2018 (n=21,249), 2020 (n=17,899), and 2022 (n=26,344) editions of EDADES was analyzed. Supplementary Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample for each survey year.

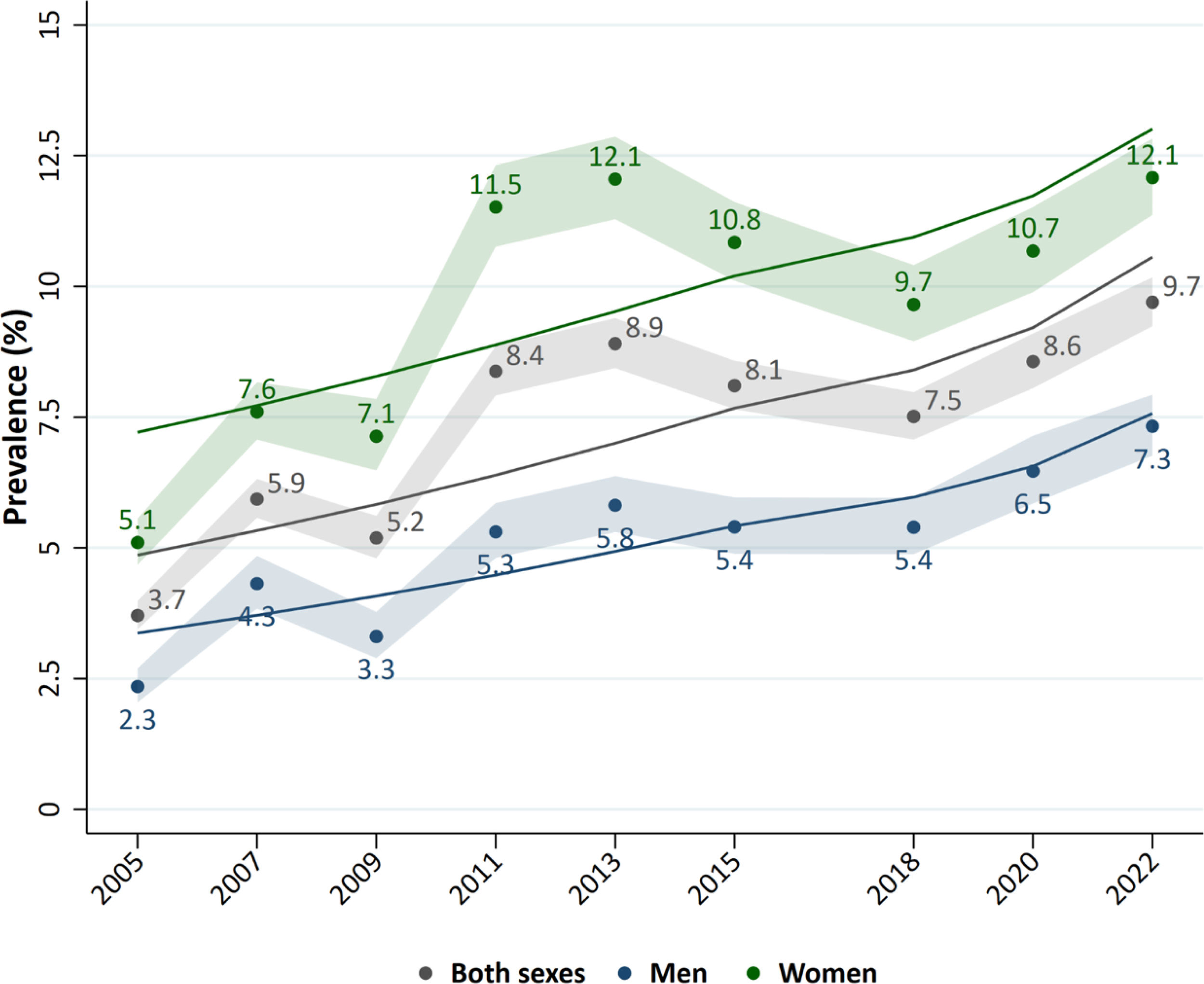

The overall prevalence of use in the last 30 days increased during the study period: it was 3.7% (95%CI: 3.4-4,0) in 2005 and 9.7% (95%CI: 9.2-10.2) in 2022. An increased trend in the prevalence of consumption was observed in both sexes. The highest prevalence of consumption in both women and men was reached in 2022: 12.1% (95%CI: 11.3-12.9) and 7.3% (95%CI: 6.8-7.9), respectively (Fig. 1).

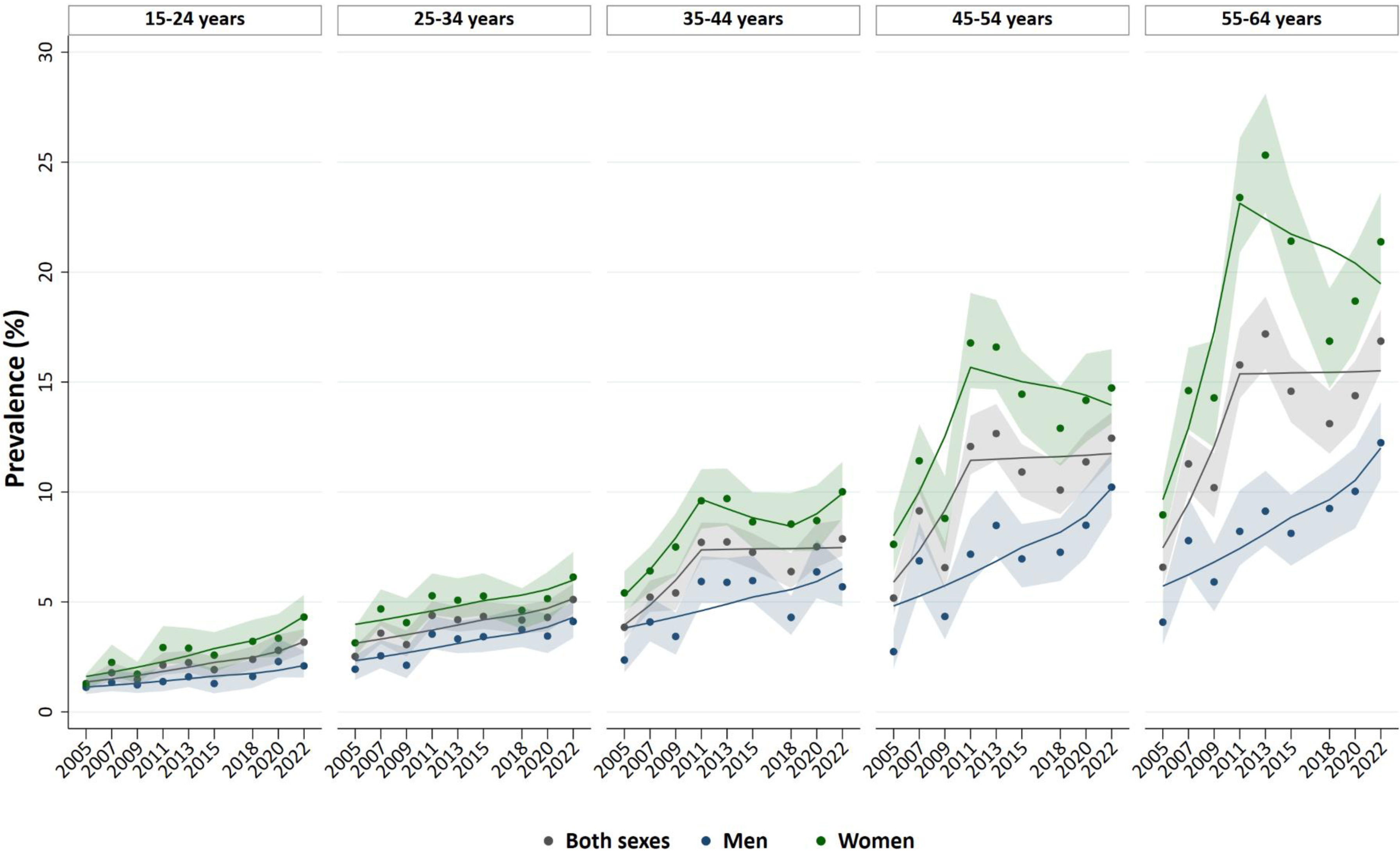

In 2022, the prevalence of hypnosedative use in the 55-64 age group exceeded that of the 15-24 age group by 13.7 percentage points: 16.9% and 3.2%, respectively (Fig. 2). Women aged 55-64 years maintained the highest prevalence of hypnosedative use in all study years (Fig. 1). When considering both sexes, the consumption trend between 2005 and 2022 showed an increase among individuals aged 15-24 and 25-34, with APC of 5.1% and 3.0%, respectively (see Supplementary Table 2). In men aged 35-44 years and women aged 45-64 years, the APC were stable during the study period (see Supplementary Table 2). In women aged 35-44 years, a fluctuating consumption pattern was observed, characterized by an increase between 2005 and 2011 (APC: 10.6%), stability from 2011 to 2017 (APC: −2.2%) and a subsequent rise between 2017 and 2022 (APC: 3.3%) (see Supplementary Table 2).

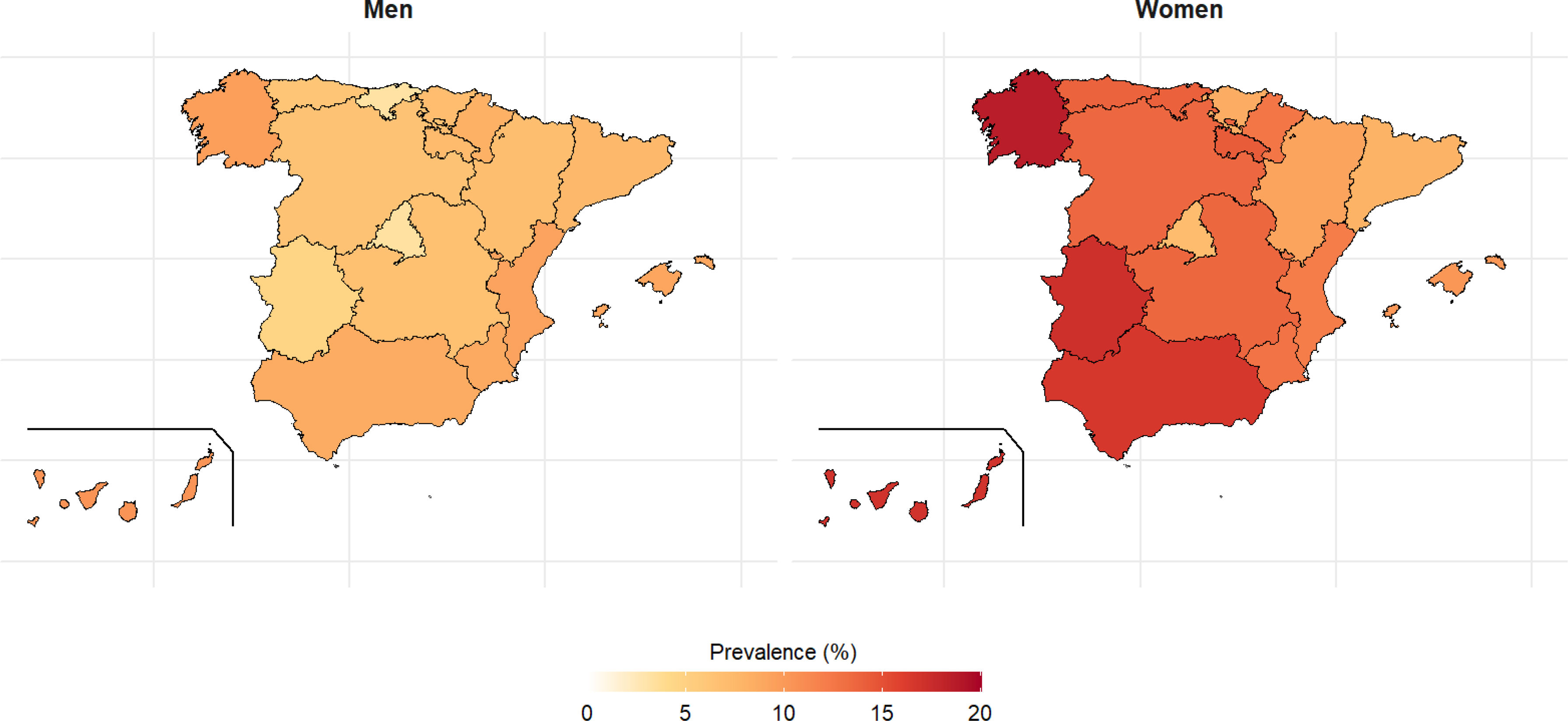

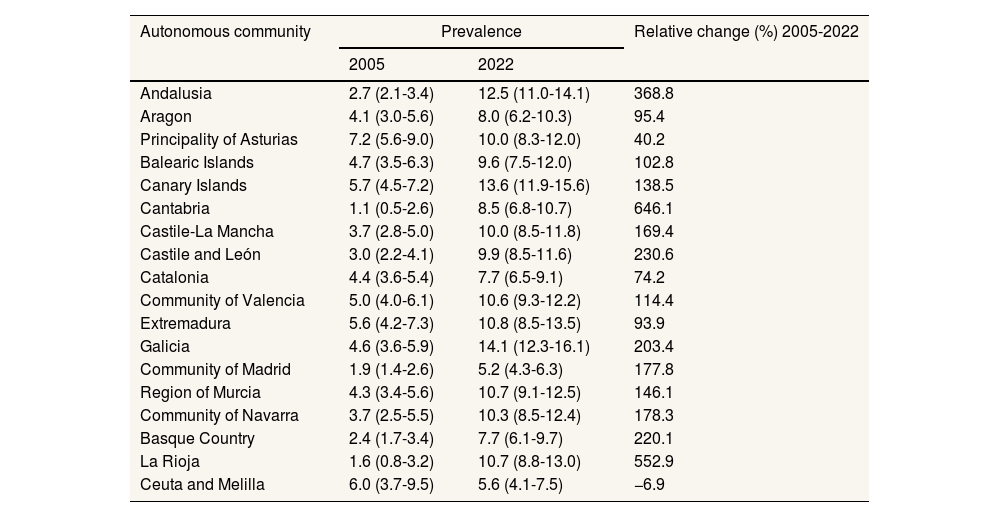

The prevalence of hypnosedative use varied according to the AC (Table 1). In 2022, the highest prevalence of consumption was observed in Galicia (14.1%), Canary Islands (13.6%) and Andalusia (12.5%). When considering the relative changes in prevalence between 2005 and 2022, the greatest increases occurred in Cantabria, La Rioja and Andalusia (Table 1). In all AC, the prevalence of consumption in 2022 was higher in women than in men (Fig. 3). The highest prevalence in women was observed in Galicia (18.5% [95%CI: 15.8-21.6]), followed by Extremadura and the Canary Islands (17.1% [95%CI: 13.2-21.9] and 16.9% [95%CI: 14.2-20.0], respectively), whereas the lowest prevalence was observed in the Community of Madrid (7.1% [95%CI: 5.7-8.9]). In men, the highest prevalence of consumption was recorded in the Canary Islands (10.4% [95% CI: 8.3-12.9]), and the lowest in the Community of Madrid (3.3% [95%CI: 2.3-4.5]) (Fig. 3).

Prevalence of hypnosedative use by autonomous community in the period 2005-2022 and relative change.

| Autonomous community | Prevalence | Relative change (%) 2005-2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2022 | ||

| Andalusia | 2.7 (2.1-3.4) | 12.5 (11.0-14.1) | 368.8 |

| Aragon | 4.1 (3.0-5.6) | 8.0 (6.2-10.3) | 95.4 |

| Principality of Asturias | 7.2 (5.6-9.0) | 10.0 (8.3-12.0) | 40.2 |

| Balearic Islands | 4.7 (3.5-6.3) | 9.6 (7.5-12.0) | 102.8 |

| Canary Islands | 5.7 (4.5-7.2) | 13.6 (11.9-15.6) | 138.5 |

| Cantabria | 1.1 (0.5-2.6) | 8.5 (6.8-10.7) | 646.1 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 3.7 (2.8-5.0) | 10.0 (8.5-11.8) | 169.4 |

| Castile and León | 3.0 (2.2-4.1) | 9.9 (8.5-11.6) | 230.6 |

| Catalonia | 4.4 (3.6-5.4) | 7.7 (6.5-9.1) | 74.2 |

| Community of Valencia | 5.0 (4.0-6.1) | 10.6 (9.3-12.2) | 114.4 |

| Extremadura | 5.6 (4.2-7.3) | 10.8 (8.5-13.5) | 93.9 |

| Galicia | 4.6 (3.6-5.9) | 14.1 (12.3-16.1) | 203.4 |

| Community of Madrid | 1.9 (1.4-2.6) | 5.2 (4.3-6.3) | 177.8 |

| Region of Murcia | 4.3 (3.4-5.6) | 10.7 (9.1-12.5) | 146.1 |

| Community of Navarra | 3.7 (2.5-5.5) | 10.3 (8.5-12.4) | 178.3 |

| Basque Country | 2.4 (1.7-3.4) | 7.7 (6.1-9.7) | 220.1 |

| La Rioja | 1.6 (0.8-3.2) | 10.7 (8.8-13.0) | 552.9 |

| Ceuta and Melilla | 6.0 (3.7-9.5) | 5.6 (4.1-7.5) | −6.9 |

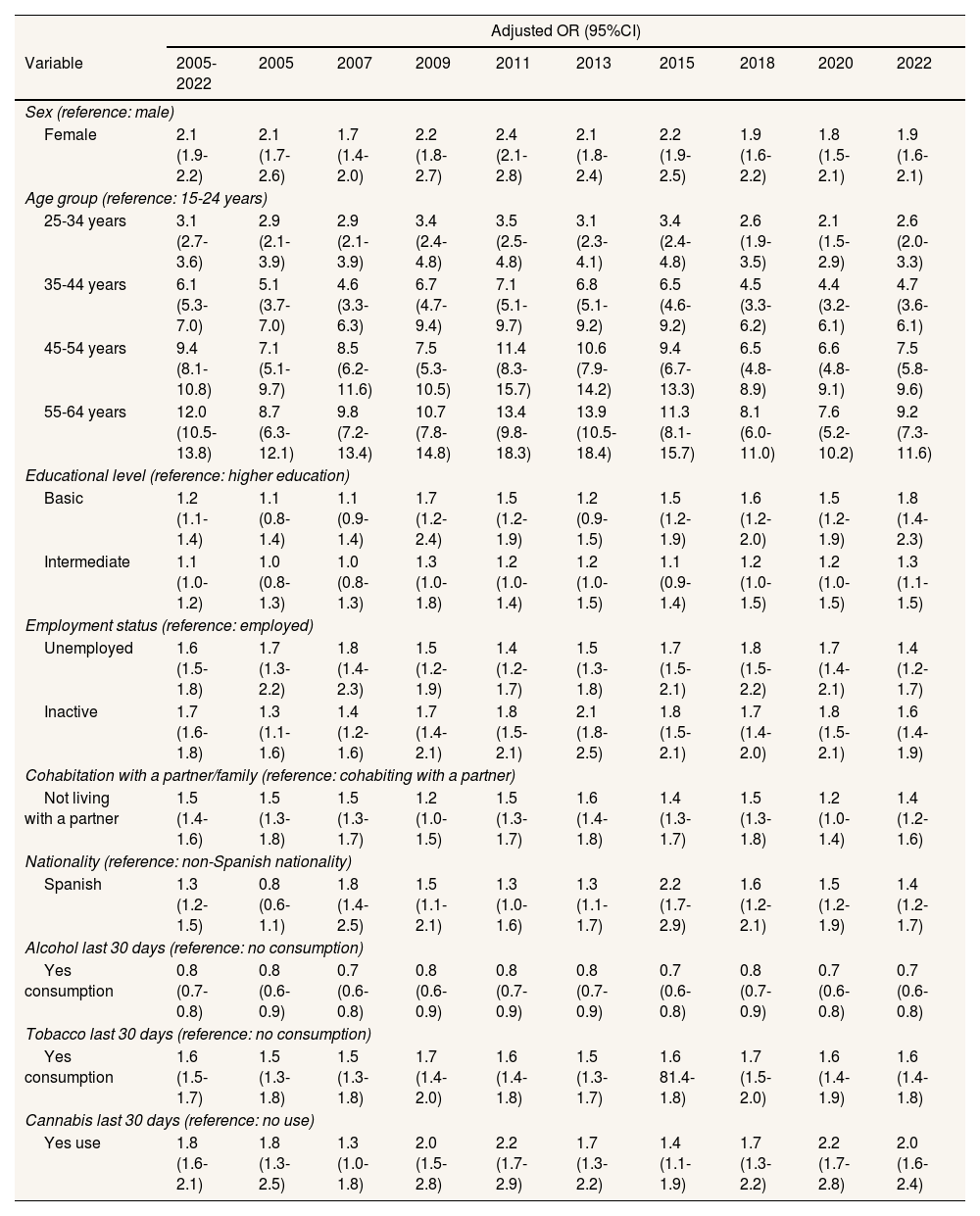

The probability of consuming hypnosedative drugs was higher among women, in older age groups, those with basic or intermediate education, unemployed or inactive people, those who do not live with a partner or immediate family, those born in Spain, and those who had consumed tobacco or cannabis in the last 30 days (Table 2).

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence interval for hypnosedative use for each year of the 2005-2020 period.

| Adjusted OR (95%CI) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | 2005-2022 | 2005 | 2007 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2018 | 2020 | 2022 |

| Sex (reference: male) | ||||||||||

| Female | 2.1 (1.9-2.2) | 2.1 (1.7-2.6) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 2.2 (1.8-2.7) | 2.4 (2.1-2.8) | 2.1 (1.8-2.4) | 2.2 (1.9-2.5) | 1.9 (1.6-2.2) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | 1.9 (1.6-2.1) |

| Age group (reference: 15-24 years) | ||||||||||

| 25-34 years | 3.1 (2.7-3.6) | 2.9 (2.1-3.9) | 2.9 (2.1-3.9) | 3.4 (2.4-4.8) | 3.5 (2.5-4.8) | 3.1 (2.3-4.1) | 3.4 (2.4-4.8) | 2.6 (1.9-3.5) | 2.1 (1.5-2.9) | 2.6 (2.0-3.3) |

| 35-44 years | 6.1 (5.3-7.0) | 5.1 (3.7-7.0) | 4.6 (3.3-6.3) | 6.7 (4.7-9.4) | 7.1 (5.1-9.7) | 6.8 (5.1-9.2) | 6.5 (4.6-9.2) | 4.5 (3.3-6.2) | 4.4 (3.2-6.1) | 4.7 (3.6-6.1) |

| 45-54 years | 9.4 (8.1-10.8) | 7.1 (5.1-9.7) | 8.5 (6.2-11.6) | 7.5 (5.3-10.5) | 11.4 (8.3-15.7) | 10.6 (7.9-14.2) | 9.4 (6.7-13.3) | 6.5 (4.8-8.9) | 6.6 (4.8-9.1) | 7.5 (5.8-9.6) |

| 55-64 years | 12.0 (10.5-13.8) | 8.7 (6.3-12.1) | 9.8 (7.2-13.4) | 10.7 (7.8-14.8) | 13.4 (9.8-18.3) | 13.9 (10.5-18.4) | 11.3 (8.1-15.7) | 8.1 (6.0-11.0) | 7.6 (5.2-10.2) | 9.2 (7.3-11.6) |

| Educational level (reference: higher education) | ||||||||||

| Basic | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 1.1 (0.8-1.4) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 1.7 (1.2-2.4) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 1.2 (0.9-1.5) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 1.6 (1.2-2.0) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) |

| Intermediate | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.1 (0.9-1.4) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.3 (1.1-1.5) |

| Employment status (reference: employed) | ||||||||||

| Unemployed | 1.6 (1.5-1.8) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | 1.8 (1.4-2.3) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 1.7 (1.5-2.1) | 1.8 (1.5-2.2) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) |

| Inactive | 1.7 (1.6-1.8) | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 1.7 (1.4-2.1) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | 2.1 (1.8-2.5) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 1.8 (1.5-2.1) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) |

| Cohabitation with a partner/family (reference: cohabiting with a partner) | ||||||||||

| Not living with a partner | 1.5 (1.4-1.6) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | 1.2 (1.0-1.5) | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 1.2 (1.0-1.4) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) |

| Nationality (reference: non-Spanish nationality) | ||||||||||

| Spanish | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 1.8 (1.4-2.5) | 1.5 (1.1-2.1) | 1.3 (1.0-1.6) | 1.3 (1.1-1.7) | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | 1.6 (1.2-2.1) | 1.5 (1.2-1.9) | 1.4 (1.2-1.7) |

| Alcohol last 30 days (reference: no consumption) | ||||||||||

| Yes consumption | 0.8 (0.7-0.8) | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 0.8 (0.6-0.9) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) | 0.7 (0.6-0.8) |

| Tobacco last 30 days (reference: no consumption) | ||||||||||

| Yes consumption | 1.6 (1.5-1.7) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 1.5 (1.3-1.8) | 1.7 (1.4-2.0) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) | 1.5 (1.3-1.7) | 1.6 81.4-1.8) | 1.7 (1.5-2.0) | 1.6 (1.4-1.9) | 1.6 (1.4-1.8) |

| Cannabis last 30 days (reference: no use) | ||||||||||

| Yes use | 1.8 (1.6-2.1) | 1.8 (1.3-2.5) | 1.3 (1.0-1.8) | 2.0 (1.5-2.8) | 2.2 (1.7-2.9) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | 1.4 (1.1-1.9) | 1.7 (1.3-2.2) | 2.2 (1.7-2.8) | 2.0 (1.6-2.4) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratios.

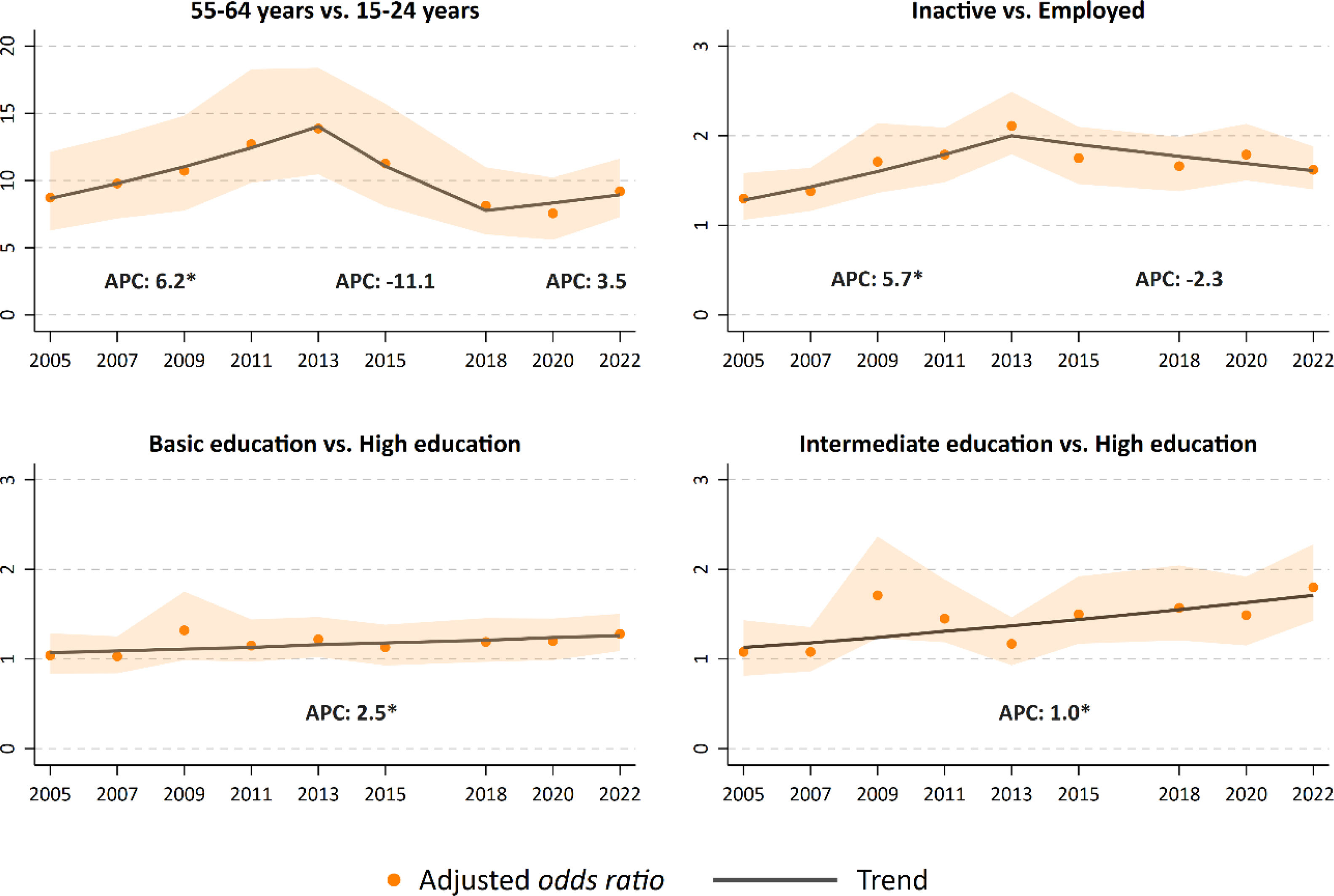

Changes have been observed in the characteristics of hypnosedative users between 2005 and 2022. Specifically, the probability of consumption varied in the 55-64 age group, in people who were inactive at work and, to a lesser extent, in people with basic and intermediate education. The probability of use in the 55-64 age group increased over time. This increase occurred in two stages: a first stage between 2005 and 2013 characterized by an increase (APC: 6.2% [95%CI: 3.6-8.8]), and a second stage of stability between 2018 and 2022 (APC: 3.5% [95%CI: −3.0-10.6]). In occupationally inactive people, the probability of consumption with respect to the employed group increased between 2005 and 2013 (APC: 5.7% [95%CI: 2.4-9.0]). Since 2013, the probability of consumption has decreased although the decrease is not significant (APC: −2.3% [95%CI: −4.7-0.1]). In those with basic and intermediate studies, the probability of consumption increased throughout the study period (APC: 2.5% [95%CI: 0.5-4.5] and 0.9% [95%CI: 0.1-1.8], respectively) (Fig. 4).

DiscussionThe results of this study show that approximately 20% of Spanish women aged 55-64 years consumed hypnosedatives in 2022. Consumption has increased since 2005 in almost all Spanish regions and age groups, including women and men aged 15-24 years. People more likely to use hypnosedatives are women, belong to an older age group, have a basic or intermediate educational level, are unemployed or inactive in the labor market, live without a partner, are Spanish citizens, and tobacco or cannabis users.

In Spain, the increase in the use of hypnosedatives has been associated with an increase in anxiety disorders and depression caused by family and economic difficulties, work stress, uncertainties and social changes resulting from the financial crisis in the 2010s.13

The prevalence of hypnosedative use in Spain peaked in 2022, a phenomenon observed elsewhere and linked to the psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.14 Stress, anxiety, insomnia, social isolation, job related worries, and uncertainty about the future contributed to the increase in demand.14 This increase has also been associated with the need to resort to medical telecare. This situation, together with the saturation of the healthcare system, could have led to rapid prescription of hypnosedatives in response to patient demands.15

Our study reveals a progressive increase in the consumption of hypnosedatives among 15 to 24-year-olds. According to the ESTUDES surveys from 2016 to 2021 in Spain,16 these drugs are the fourth most consumed substances among high school students. In 2021, approximately 20% of Spanish students had tried hypnosedatives.16 This trend is also observed at the European level, according to the ESPAD17 study, which highlights a significant increase in the use among young men and women during the period 2005-2019. The stress generated by academic pressure, social dependence, body image issues, economic difficulties, and uncertainty about the future may explain the increase in use among adolescents.18 Accessibility to hypnosedatives in the home may also play a crucial role in consumption. Parents, particularly mothers, may offer them to alleviate their children's distress, unaware of the associated dangers.19 Several studies link consumption among young people with social determinants such as the lower educational level of parents.20

The differences observed between AC can be explained by factors such as the prevalence of mental disorders, the aging index, the unemployment rate, or the preventive strategies implemented in AC. According to data from the European Health Survey in Spain, in 2020, Asturias, Galicia and Castile and Leon had the highest prevalence of depression, and Galicia and the Canary Islands had the highest prevalence of chronic anxiety. This could explain their higher prevalence of use compared to other AC.21 In this study, we observed that hypnosedative consumption increases with age, and communities such as Asturias, Galicia and Castile and Leon had the highest aging index in 2023.22 In addition, unemployment is associated with higher hypnosedative consumption23 and in 2023, data from the Labour Force Survey indicated that Andalusia, the Canary Islands and Extremadura had the highest unemployment rates among all AC.24 Other studies carried out in Seville (Andalusia) and Castilla and Leon have also shown this increase over the same time period.7 It is worrying that the regional addiction plans do not adequately reflect this reality. For example, the Andalusian Plan on Drugs and Addictions25 does not prioritize hypnosedative use, even though our data shows that in 2022, Andalusia ranked among the top three regions for consumption. Recently, the Andalusian Health Service has launched the BenzoStopJuntos campaign to raise awareness. Early reports suggest a reduction in prescription rates across most provinces.

Older Spanish women are the main consumers of hypnosedatives.5 Our study revealed a 21.4% prevalence of use among Spanish women aged 55-64 in 2022. However, the absence of comparable national or international data for this age group and year limited our ability to fully interpret these findings. This highlights the need for additional research that provides recent prevalence rates, categorized by sex and age group, to allow for more meaningful comparisons and a better understanding of trends. In addition to the increase observed among older women, our findings reveal the need for a focused investigation into the factors driving use in the younger demographic because of a concerning rise in consumption among women in their teens and early twenties. An intersectional approach, which considers both age and gender, is crucial for developing effective prevention and intervention strategies. A thorough understanding of the social, psychological, and cultural factors contributing to this increase will aid in creating targeted policies and educational initiatives.

The higher prevalence of use among women may be linked to the greater incidence of somatization disorders, anxiety, and depression. Women's greater awareness of mental health and their predisposition to seek professional help, as well as the high prevalence of mental disorders could influence the greater demand.18 The attitude of health professionals could also contribute to gender disparity. Sometimes, the therapeutic approach with female patients focuses more on psychological aspects than on the physical causes of their symptoms, in contrast to men.26 Understanding the causes of higher hypnosedative use in women is crucial to develop more effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Being born in Spain also appears to be a factor associated with hypnosedative use, which could be attributed to various demographic, socioeconomic, cultural, and health system factors.27 Cultural rules around stress management, and easy access to medications could have contributed to the increase in use among those born in Spain.27

Previous studies, in line with our results, have shown a relationship between low socioeconomic status, as measured by educational level and/or employment status, and higher hypnosedative use. This association is mainly attributed to the higher levels of anxiety and depression, probably attributed to poorer working conditions and opportunities, greater exposure to stressful situations in precarious jobs, and difficulties in accessing mental health services.5,13,28 To address these disparities, it is crucial to implement policies that ensure equitable access to healthcare and provide robust social support. Social prescribing, which connects individuals to community-based services that address underlying social and economic factors, has shown promise in improving mental health and reducing visits to primary care and emergency services by addressing social needs.29 Further research is necessary to confirm the potential reduction of reliance on hypnosedatives.

Education is a fundamental social determinant of health and should be prioritized in public health interventions.30 The European Union's Health in All Policies approach exemplifies the integration of health considerations across various policy areas, recognizing that many factors influencing health extend beyond the healthcare sector.30 Frieden's Health Impact Pyramid emphasizes the considerable public health benefits of targeting social determinants such as education. Interventions at the base of the pyramid have the potential to improve population health on a broad scale, reduce health inequities, and yield long-term benefits by addressing root causes.30

Zimmerman et al.31 highlights the importance of contextual factors in understanding the relationship between education and health; these factors can influence educational attainment and contribute to poorer mental health outcomes. Aligning with the psychosocial environment model by Hahn and Truman,30 which emphasizes the role of social support and stress in health outcomes, integrating these insights into policy and practice, particularly through comprehensive models like Integrated Care Systems, can effectively address these social determinants and help reduce health inequalities.32

Our results show that the use of psychoactive substances such as tobacco and cannabis increases the probability of consuming hypnosedatives in the Spanish population. This relationship could be attributed to the higher prevalence of mental disorders in less advantaged socioeconomic contexts, where tobacco and cannabis use is more common.33 In contrast, alcohol consumption is associated with a lower likelihood of consuming hypnosedatives, possibly because it is perceived as an alternative for treating anxiety and depression.27

This study has both strengths and limitations. Among its strengths, the sample size stands out, as well as the correspondence of the EDADES questionnaire and methodology with those used in other countries of the European Union and the United States, facilitating international comparisons.10 In addition, the representativeness of the population and the inclusion of recent EDADES data, collected over 17 years, provide a detailed view of trends in hypnosedative use. This study is a pioneer in assessing the temporal evolution of consumption, characterizing consumers, and providing specific prevalence data for each AC of Spain, thus enriching the understanding of regional disparities in consumption patterns.

However, the study has limitations. Hypnosedative use is self-reported, which may introduce misreporting biases.34 Nevertheless, the survey's confidentiality and the social acceptance of hypnosedatives mitigate potential social desirability bias. The survey adds value by capturing data not typically included in real world data analyses, which primarily focus on prescribed medications. The survey also captures nonprescription and over-the-counter use, enhancing the robustness of findings. However, the low prevalence of nonprescription use makes detailed analysis challenging, as stratification could yield imprecise estimates. Additionally, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference regarding variable associations and does not differentiate between occasional and prolonged use. Future studies should include individual data to understand long-term implications better.

The lack of data on variables like job type and working hours restricts exploration of factors influencing consumption patterns.35 Furthermore, the limited number of data points in joinpoint regression models hampers accurate estimates of consumption trend changes. Finally, regional prevalence could not be analyzed by sex and age jointly due to small sample sizes in each AC.

ConclusionsOur study highlights a significant rise in hypnosedative consumption in Spain from 2005 to 2022, with notable demographic and geographic disparities. Older women remain the largest user group, while a worrisome increase is emerging among younger populations. These findings highlight the need for comprehensive public health interventions.

In addition, regional disparities further emphasize the importance of tailored strategies. To address these variations, addiction plans in each AC must incorporate current prevalence data and customize interventions to specific consumer profiles. Effective management requires ongoing monitoring of consumption patterns and emerging trends, prioritizing early intervention, harm reduction, and expanded access to comprehensive treatment services.

Hypnosedative users are predominantly women, older adults, individuals with lower education levels, the unemployed, and those with recent tobacco or cannabis use. Targeted interventions for these high-risk groups should include integrating mental health support into substance use treatment and promoting responsible prescribing practices. Regular prescription monitoring and reassessment is vital to prevent misuse and ensure treatments remain appropriate and effective.

Health plans must be regularly updated to address hypnosedative use by incorporating preventive measures, targeted interventions, and mental health services. These updates will enhance care coordination, expand access to treatment, and improve the management of substance-related issues. Ongoing research is essential to ensure strategies are grounded in the latest data and best practices.

This study provides a foundation for future research to explore the underlying causes of these trends and evaluate the effectiveness of implemented interventions. A deeper understanding of the factors driving hypnosedative use will be key to developing more precise and impactful prevention strategies.

People with mental health issues often receive prescriptions for psychotropic drugs such as hypnosedatives. Concern is rising over the prolonged use of hypnosedatives and their adverse health effects. Spain is among the countries with the highest consumption of these substances worldwide.

What does this study add to the literature?This study is a pioneer in providing data on the hypnosedative consumption trends in Spain from 2005 to 2022, characterizing consumers, and detailing specific regional disparities in prevalence.

What are the implications of the results?Findings emphasize the need for focused prevention strategies. Collaboration among healthcare sectors and authorities is crucial to address mental health disparities and ensure responsible prescribing.

Salvador Peiró.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsN. Mourino participated in the methodology, extraction and analysis of results, writing, review and editing of the manuscript. A. Teijeiro extracted and analyzed results, reviewed and edited the manuscript. M. Pérez-Ríos acquired the funds and participated in the conceptualization, methodology, extraction and analysis of results, and review and editing of the manuscript. C. Guerra-Tort participated in the methodology, extraction and analysis of results, and review and editing of the manuscript. L. Varela-Lema, J. Rey-Brandariz, C. Candal-Pedreira, L. Martín-Gisbert, M. Mascareñas-García and G. García participated in the review and editing of the final manuscript.

FundingThis work was supported by a project of the National Plan on Drugs (code 2022I006).