After expiry of the patent, price competition can lead to savings. However, in Spain, competition in the retail price of prescription off-patent medicines in pharmacies is rare, while large discounts are negotiated in the wholesale market. Some countries have moved from “competition by discount” to “competition by price”. This article compares retail prices in Spain with other countries, and the factors that promote price competition.

MethodThis article reviews the literature comparing prices and the factors influencing competition. A detailed analysis of the design of the market was conducted for Spain and Sweden. Interviews were conducted with experts. The systems were compared for the definition of exchange groups, prescription and substitution, how retail prices and profit margins are regulated, and safeguards to avoid risk of shortages.

ResultsDepending on sample and methodology, prices in Spain may be on average 51% to 109% greater than Sweden. Broadly, the literature recommends that the off-patent market should be regulated by competitive forces rather than price caps. Spain and Sweden have many features in common. Key differences are: 1) Sweden allows price differences between medicines, and for prices to rise as well as fall, 2) the tendering process, 3) patient choice, and 4) the architecture of the exchange groups

ConclusionsIn Spain, first generic or biosimilar entry provokes a 25-40% discount, but thereafter prices are static. In Sweden, price competition is dynamic. This includes, within limits, freedom to set prices, product differentiation, and patient choice.

En España, la competencia en el precio de venta al público de los medicamentos sin patente con receta en las farmacias es escasa, mientras que en el mercado mayorista se negocian grandes descuentos. Algunos países han pasado de la «competencia por descuento» a la «competencia por precio». Este artículo compara los precios en España con los de otros países, y los factores que promueven la competencia.

MétodoSe realizaron una revisión de la literatura y un análisis detallado del diseño del mercado en España y Suecia. Se llevaron a cabo entrevistas con expertos. Se compararon los sistemas para la definición de las agrupaciones homogéneas, la prescripción y la sustitución, cómo se regulan los precios y los márgenes, y las salvaguardas para evitar el desabastecimiento.

ResultadosDependiendo de la metodología, los precios en España pueden ser entre un 51% y un 109% mayores que en Suecia. La literatura recomienda que el mercado sin patente se regule por las fuerzas competitivas en lugar de por topes de precios. España y Suecia tienen muchas características en común. Las diferencias clave son: 1) Suecia permite diferencias de precios, 2) la subasta, 3) la elección del paciente, y 4) la arquitectura de las agrupaciones homogéneas.

ConclusionesEn España, la primera entrada de un genérico o biosimilar provoca un descuento del 25-40%, pero luego los precios son estáticos. En Suecia, la competencia de precios es dinámica. Esto incluye, dentro de unos límites, la libertad de precios, la diferenciación de productos y la elección del paciente.

Once a medicine loses its patent and other market and data protections, competitor companies can market generic or biosimilar versions. Nevertheless, the off-patent market also presents challenges for medicine regulators and health systems. In some countries, entry of generics or biosimilars leads to competition in retail prices, with financial savings for the benefit of patients and health systems,1–3 but in other circumstances, the competition manifests as discounts in the wholesale price negotiated between community pharmacies and manufacturers.4 There are also concerns about the risk of very low prices (by competition or imposed by regulation) on continuity and security of supply,5–9 the reaction of patients to changes in their medicine,10,11 and the risk of price spikes.12,13

This article discusses the current system for pricing and dispensation of off-patent medicines in community pharmacies in Spain and how it might be better regulated for the benefit of patients and the national health service. The community pharmacy is a crucial intermediary between the patient, the prescriber, and the regional health authority (the health service payer), providing for many patients a vital service and advice from a health professional without the need for an appointment. The law governing reimbursement of medicines14 is extremely complex, regulating the prices of the medicines, how community pharmacies are reimbursed, the profit margins of the pharmacies, the prescription, and substitution by the pharmacist of lower-priced alternatives. A reform of this law is imminent,15 presenting an opportunity to make it work more effectively, while providing adequate supply-side incentives for pharmacies and manufacturers.

Spain in 2003 established a reference price system (RPS) for off-patent medicines. In its original form, the RPS was designed as a mechanism to encourage price competition and use of generics.16 In a RPS, the regulator or health ministry decides on a single maximum reimbursement price for a group of equivalent medicines (an “exchange group”), and then the patient pays the difference if the chosen medicine is more expensive.17 Companies in an RPS are free to set their own prices (often within maximum and minimum limits).

The legislation in Spain was then modified several times over the next 20 years, until it has become a “pseudo-RPS”;16de facto, it has been transformed into a system for direct price control. Many of the modifications were intended to unilaterally force reductions in prices, especially as urgent cost-cutting measures during the 2008-2012 financial crisis.16 Under the current regulation, the entry of the first generic alternative is usually accompanied by a reduction in the price compared with the original patented medicine of 40%.18,19 Prices for biosimilar alternatives are negotiated, and usually represent a discount of about 25-30% compared with the price of the originator brand.18 In principle, a manufacturer can voluntarily choose to lower the retail price of their product to capture a larger market share14 (13th disposition). However, all medicines in an exchange group are required to lower their price within 3 months to match that of the product with the lowest price14 (Article 98). Therefore, this system generates tacit incentives among manufacturers not to voluntarily reduce the retail price.10,16 In the first 9 months after the introduction of the mechanism, there were 60 requests for voluntary price reductions, but this represented only 0.56% of medicines in the RPS. There were few further requests from 2015 to 2019.20 Indeed, the voluntary price reductions requested in 2022 and 2025 were so unusual that the phenomena generated reports in the national newspapers.21,22

Instead, manufacturers or distributors negotiate wholesale price discounts with the retail pharmacies to increase market share, as it is the pharmacist, and not the doctor or the patient, who acquires stock from the manufacturers and chooses which product to dispense within the alternatives allowed in the exchange group.18,20 This occurs despite the law only allowing non-exclusive discounts for early payment or volume, and where they do not influence the dispensing decision14 (Article 4). This regulation has been circumvented by “two-for-one” type deals,23 or declared on invoices as if they were discounts on the wholesale prices of over-the-counter medicines, which the pharmaceutical manufacturers bundle together with the supply of prescription medicines and represent almost one-third of total expenditure on retail medicines in Spain.24

Competitive discounts in the distribution chain have been observed in other countries, notably the UK, France,4 Poland25 and Netherlands.26 Indeed, these discounts are greatest when there are more competitors,27 indicating that generic entry almost always induces vigorous price competition, but that, in systems with rigid retail price regulation, the financial savings from this competition are displaced in favour of pharmacies and distributors, at the expense of patients and health systems.26,28 A possible reason is that a retail price cap acts as a focal point for prices.29 Numerous studies have found that, on a like-for-like comparison, ex-factory (i.e. before tax and retailers’ fees) prices for medicines with competition vary substantially between European countries,1,29–41 suggesting that the extent to which prices approach long-run marginal costs may be influenced by the regulatory environment.30

Some countries have been remarkably successful in moving away from “competition by discount in the distribution chain” to “competition by retail price”.26,28 In Sweden and Denmark, this has been achieved by auction or tendering systems, and prices in these countries are amongst the lowest in Europe.

This article compares the working of the Swedish model with the Spanish system. Sweden is a good benchmark because the system has been essentially unchanged since 2010,29 and has generated substantial savings from price competition, rather than price cuts.42 Crucially, the Spanish and Swedish systems have many key features in common, as will be explained in the following sections. Nevertheless, there are differences, and the literature shows that apparently small modifications to the regulatory system can have substantial impact on the incentives faced by the private economic agents involved (the community pharmacies, the manufacturers and the patients) and their behaviour.43–47 It is hypothesised that these differences are the features that encourage competitive by retail price, rather than by discounts for distributors, and by systematically identifying these factors, it may be possible to make recommendations to reform the system in Spain without excessive costs of transition, while retaining essential safeguards to protect against shortages and price spikes.18,48

MethodA literature review was conducted to compare prices of off-patent medicines in Spain with other countries, and identify the factors influencing prices (see Supplementary Material). A detailed comparison was made of the price and reimbursement systems in Spain and Sweden, described in law and normative documentation. In Spain, this is the Royal Legislative Decree 1/2015 of 24th July.14 In Sweden, this is available on the Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency (TLV) website,49 translated to Spanish and English using the premium version of DeepL (Cologne, Germany). To check facts and obtain a first-hand interpretation, one-hour face-to-face discussions were scheduled with experts from Sweden and Spain (see Acknowledgements). The systems were compared with the following questions in mind, which the literature highlights as key parameters of a price and reimbursement system for off-patent medicines:10,34,45

- •

How tightly are the exchange groups defined (e.g. are active ingredient, dose, route of administration, pack sizes and the pharmaceutical form the same for all medicines in the group)?

- •

Which medicine is prescribed (e.g. the commercial name; the non-proprietary name), does the pharmacist substitute for another (e.g. a generic or biosimilar alternative; the cheapest within the interchangeable group) and can the patient choose a more expensive alternative and pay the difference?

- •

How are the ex-factory prices of the medicines set (e.g. by regulation; by the manufacturer), are there maximum and minimum prices, and how often are they updated (e.g. monthly; yearly; at the decision of the manufacturer?)

- •

How are the profit margins or fees of the dispensing pharmacist regulated (e.g. fixed fee per prescription; proportion of price of medicine?)

- •

What safeguards are in place to avoid risk of shortages?

The literature review identified 78 relevant papers. These were classified in five themes (see Supplementary Material): empirical studies comparing prices of off-patent or generic medicines in Spain, Sweden and other countries; the design and regulation of markets for off-patent medicines; factors influencing generic entry and exit and the degree of competition; factors influencing pharmacy margins and discounts; and factors influencing shortages and price spikes.

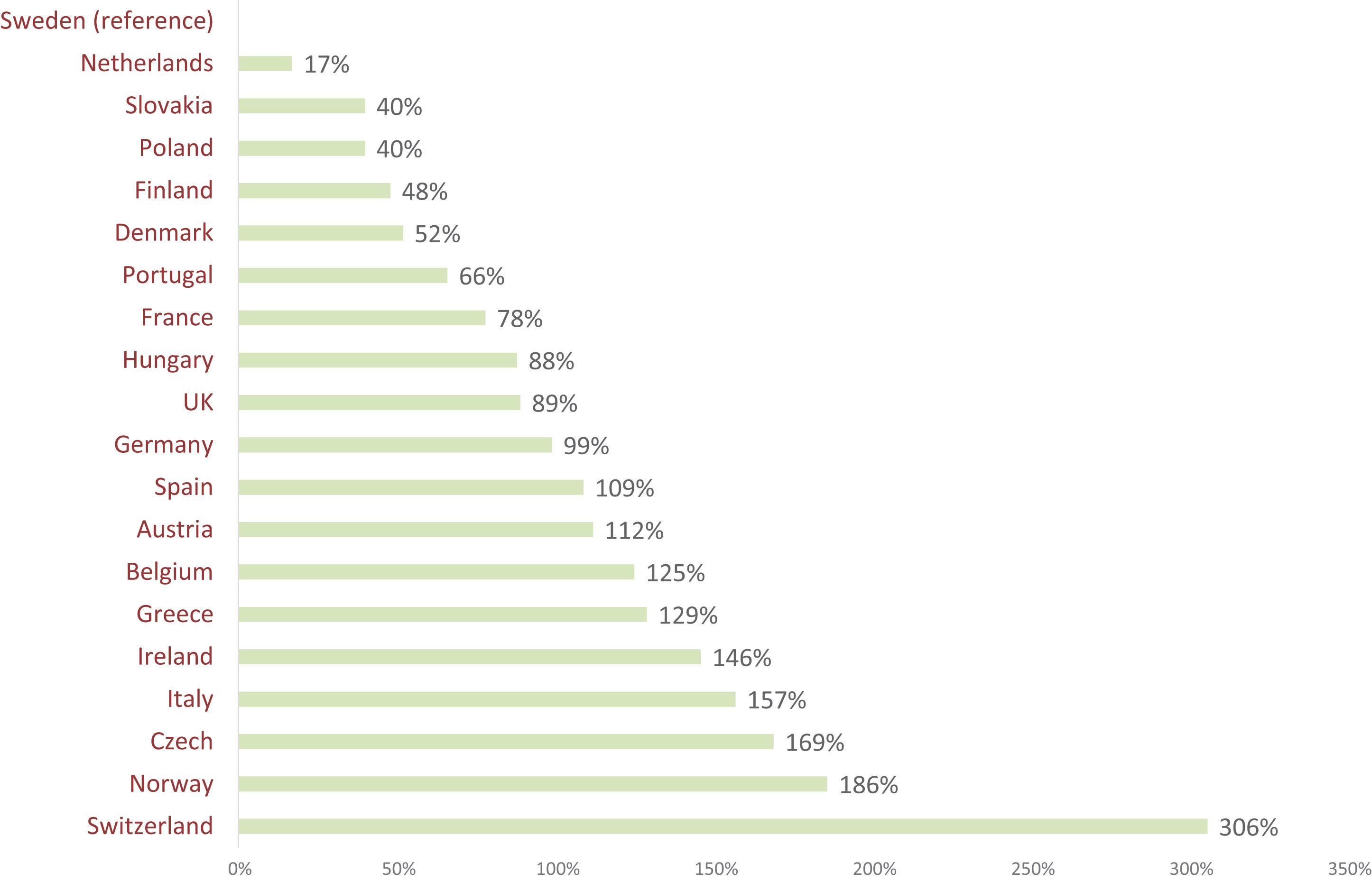

Prices of off-patent and generic medicinesDepending on the sample and methodology, prices of off-patent medicines with competition have been estimated to be 51%,41 64%36 or 109%40 (Fig. 1) greater in Spain than Sweden (see Supplementary Material). These figures are weighted averages; in some specific cases, prices are lower in Spain.36

Matched comparison of prices for off-patent medicines with competition in 2020, compared with prices in Sweden.40

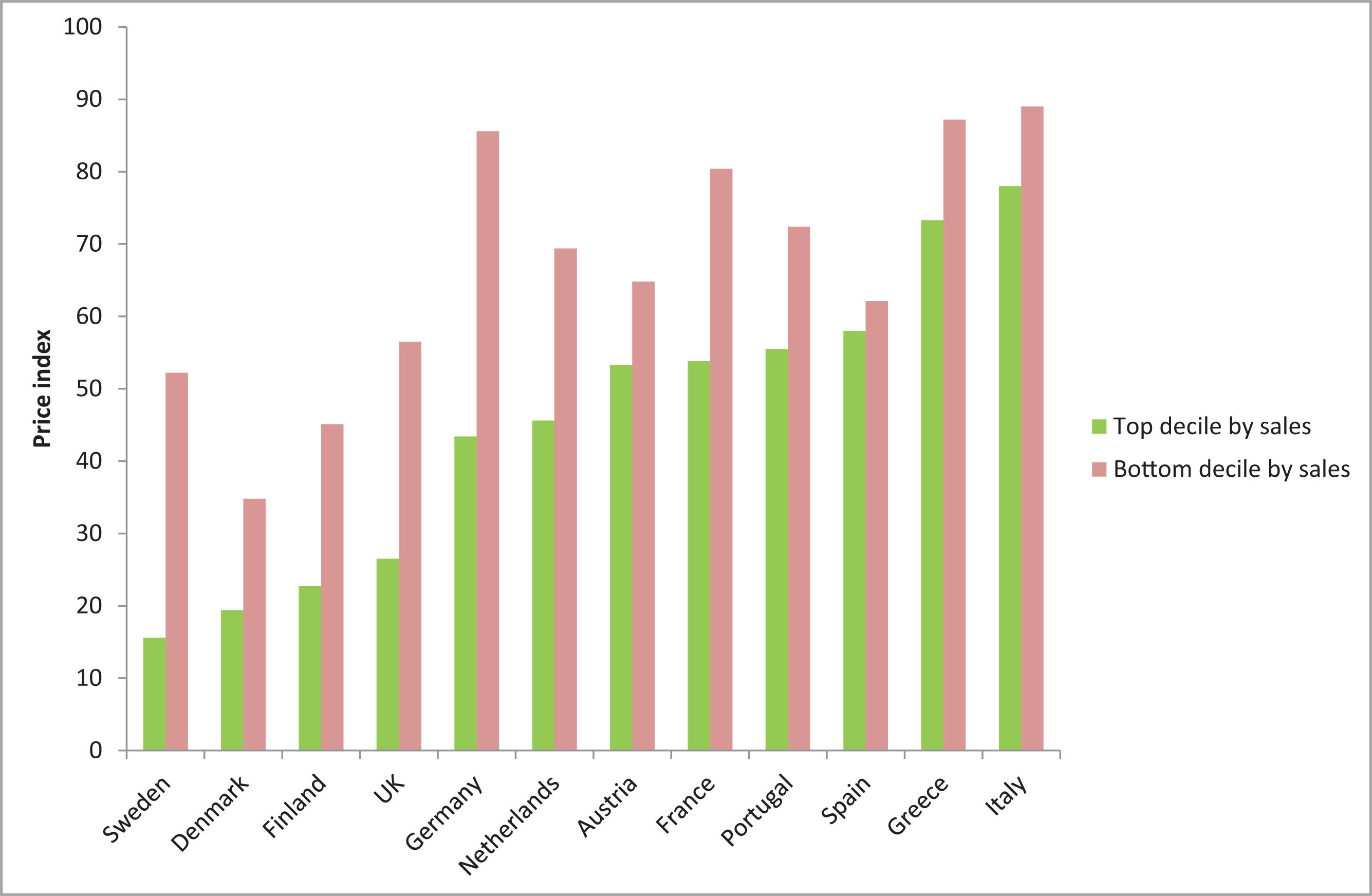

After generic entry in Spain, retail prices for both generic and original medicines fall by 40% but subsequently have tended to be static over time.34Figure 2 shows that in most countries, the discount is greater in high-volume markets than low-volume markets (indicating that the discount arises from competitive pressure) but retail prices in Spain are 40% lower after generic entry irrespective of volume (indicating the discount arises from regulation). There is little difference between the price of original and generic alternatives after generic entry.50,51

Volume-adjusted price indices 24 months after patent expiry for all molecules with generic entry in the top decile and bottom decile by sales. The price index on the vertical axis refers to the price of pharmaceuticals 24 months after generic entry, compared with the price before generic entry (index value of 100).34

In Sweden, retail prices reductions average 40% after 3 months and 65% after 2 years.42 While the general trend in Sweden is for prices to fall, they can increase month-on-month (for example, as occurred for rampiril36). In exchange groups with zero, one or two competitors, the reduction is only around 20%, but in groups with 5 or more competitors, reductions reach on average 70% after 6 months and 90% after 2 years.42 Another study estimated the price of generics to decrease by 81% when the number of firms in the same exchange group is increased from 1 to 10.35 Only competition within exchange groups matters; the effect of competition in one exchange group on firms selling the same active substance in another exchange group is only a tenth as large.35 In Spain, there are 6.7 competitors per exchange group compared with 3.2 in Sweden,34 but unlike Sweden, in Spain the retail price discount is the same regardless of the number of competitors.

The discounts offered by manufacturers to pharmacies in Spain have been estimated to average around 30-40% 10,23,27 and that discounts are greater when there are more competitors in an exchange group.4 Confidential discounts in the distribution chain can be negotiated In Sweden for parallel imports competing with patent brands43, but are not permitted in the off-patent market.35

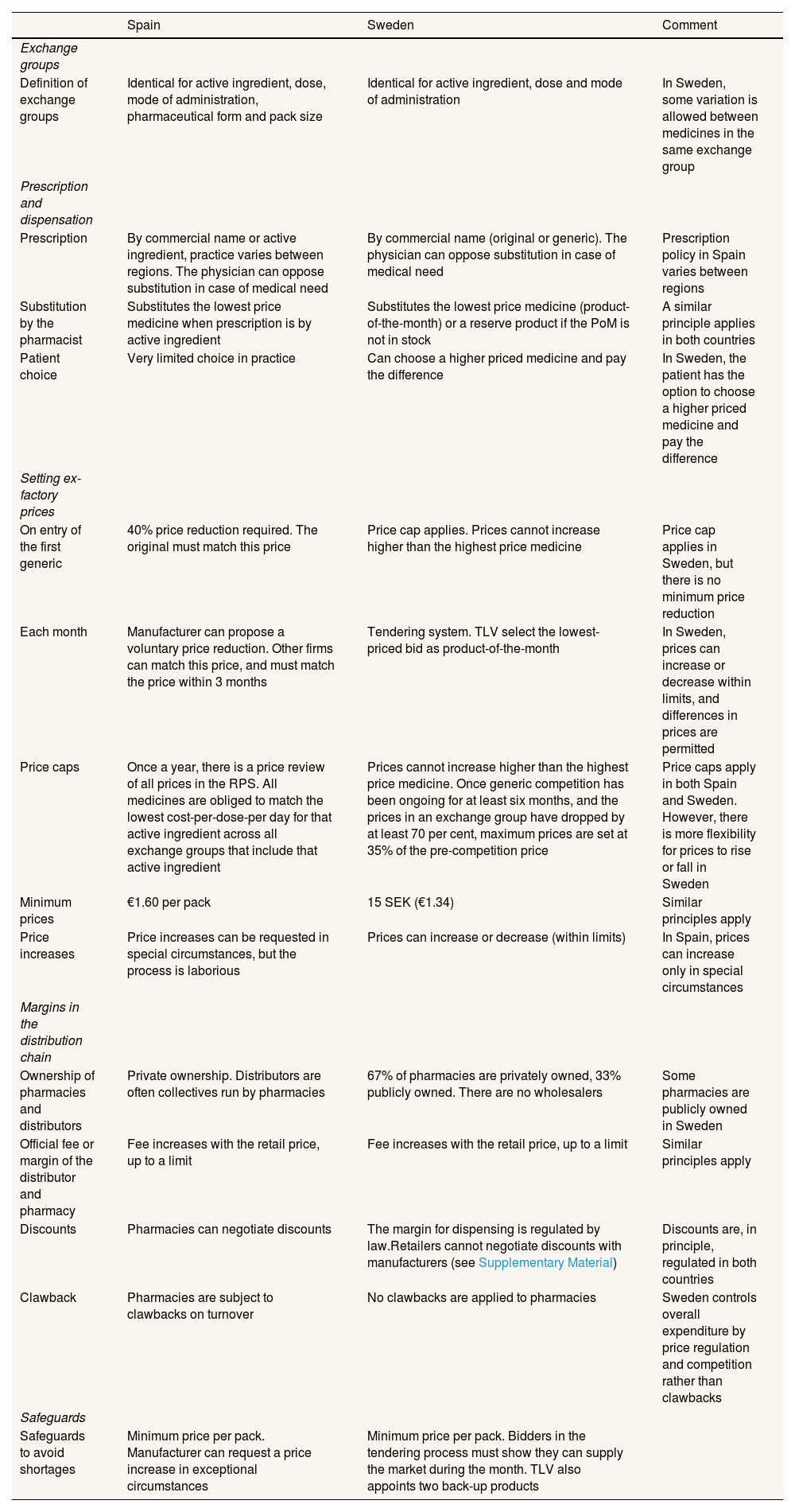

The design and regulation of markets for off-patent medicinesA detailed narrative description of both systems is given in the Supplementary Material. It is instructive to compare Sweden with Spain because the systems share many features (Table 1). Regulators in both systems define “exchange groups” of medicines that are chemically equivalent, and the pharmacist is usually required to substitute the product with the lowest price. Both systems set a maximum and minimum range within which prices can vary. Both systems have mechanisms to allow manufacturers to reduce retail prices to capture greater sales. Both systems regulate the distribution and dispensing margin between the official ex-factory price and the retail price. Both systems disallow, or place narrow limits on, the ability of the pharmacy to negotiate prices directly with the manufacturer or distributor. Nevertheless, the systems differ in significant details. In Spain these features incentivise competition by sometimes opaque discounts to pharmacies, whereas in Sweden the system is configured to broadly encourage competition in the retail price.

Parameters of the pricing and reimbursement systems for retail prescription medicines with generic competition in Spain and Sweden.

| Spain | Sweden | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange groups | |||

| Definition of exchange groups | Identical for active ingredient, dose, mode of administration, pharmaceutical form and pack size | Identical for active ingredient, dose and mode of administration | In Sweden, some variation is allowed between medicines in the same exchange group |

| Prescription and dispensation | |||

| Prescription | By commercial name or active ingredient, practice varies between regions. The physician can oppose substitution in case of medical need | By commercial name (original or generic). The physician can oppose substitution in case of medical need | Prescription policy in Spain varies between regions |

| Substitution by the pharmacist | Substitutes the lowest price medicine when prescription is by active ingredient | Substitutes the lowest price medicine (product-of-the-month) or a reserve product if the PoM is not in stock | A similar principle applies in both countries |

| Patient choice | Very limited choice in practice | Can choose a higher priced medicine and pay the difference | In Sweden, the patient has the option to choose a higher priced medicine and pay the difference |

| Setting ex-factory prices | |||

| On entry of the first generic | 40% price reduction required. The original must match this price | Price cap applies. Prices cannot increase higher than the highest price medicine | Price cap applies in Sweden, but there is no minimum price reduction |

| Each month | Manufacturer can propose a voluntary price reduction. Other firms can match this price, and must match the price within 3 months | Tendering system. TLV select the lowest-priced bid as product-of-the-month | In Sweden, prices can increase or decrease within limits, and differences in prices are permitted |

| Price caps | Once a year, there is a price review of all prices in the RPS. All medicines are obliged to match the lowest cost-per-dose-per day for that active ingredient across all exchange groups that include that active ingredient | Prices cannot increase higher than the highest price medicine. Once generic competition has been ongoing for at least six months, and the prices in an exchange group have dropped by at least 70 per cent, maximum prices are set at 35% of the pre-competition price | Price caps apply in both Spain and Sweden. However, there is more flexibility for prices to rise or fall in Sweden |

| Minimum prices | €1.60 per pack | 15 SEK (€1.34) | Similar principles apply |

| Price increases | Price increases can be requested in special circumstances, but the process is laborious | Prices can increase or decrease (within limits) | In Spain, prices can increase only in special circumstances |

| Margins in the distribution chain | |||

| Ownership of pharmacies and distributors | Private ownership. Distributors are often collectives run by pharmacies | 67% of pharmacies are privately owned, 33% publicly owned. There are no wholesalers | Some pharmacies are publicly owned in Sweden |

| Official fee or margin of the distributor and pharmacy | Fee increases with the retail price, up to a limit | Fee increases with the retail price, up to a limit | Similar principles apply |

| Discounts | Pharmacies can negotiate discounts | The margin for dispensing is regulated by law.Retailers cannot negotiate discounts with manufacturers (see Supplementary Material) | Discounts are, in principle, regulated in both countries |

| Clawback | Pharmacies are subject to clawbacks on turnover | No clawbacks are applied to pharmacies | Sweden controls overall expenditure by price regulation and competition rather than clawbacks |

| Safeguards | |||

| Safeguards to avoid shortages | Minimum price per pack. Manufacturer can request a price increase in exceptional circumstances | Minimum price per pack. Bidders in the tendering process must show they can supply the market during the month. TLV also appoints two back-up products | |

PoM: product of the month; RPS: reference price system; SEK: Swedish Krona; TLV: Sweden Dental and Pharmaceutical Benefits Agency.

The weak incentives for retail price competition in Spain means that patients (through co-payments) and the regional health authorities are paying higher retail prices than the market will bear, and this represents a transfer of economic surplus in favour of pharmacies and manufacturers, at the expense of patients and taxpayers.

The key features that differ between the Spanish and Swedish system can be summarised as 1) price differences between medicines, 2) the tendering process, 3) patient choice, and 4) the architecture of the exchange groups.

Authors in Spain, Sweden and other countries overwhelmingly agree that differences in prices, particularly between the original and generics, is crucial for promoting competition and allowing generics to gain market share.10,17,18,20,26,28,30,33,46,50,52–56 Spain forces all retail prices to be the same, and cannot easily be increased. Manufacturers prefer to negotiate discounts with pharmacies because they can be reversed if market conditions change and because they do not affect external reference prices.43 Unlike Spain, manufacturers in Sweden can increase or reduce retail prices month-on-month. Low prices are one of the principal reasons for firms to leave the market5,6,9, and the flexibility to increase prices provides a safeguard against changes in prices of raw materials or exchange rates, and reduces risk of stock-outs.

In the current system in Spain, manufacturers can voluntarily reduce retail prices to gain market share, but prefer to compete with discounts. Sweden, Denmark, Hungary and Netherlands have implemented tender mechanisms with broadly positive results.26,31,57 Disadvantages of the tendering model have been raised in theory and practice, though some of these can be safeguarded. The lowest-priced medicine may change, with different colour or form, which may affect adherence by elderly and chronic patients.11 This can be mitigated by permitting the physician or pharmacist to block the substitution for medical reasons. Delivery problems can arise particularly where smaller companies win the bid.11 This can be mitigated by appointing reserve products, or requiring winning manufacturers to have minimum inventories to hand.7 Frequent changes of the selected product may create stock problems for pharmacists. In Sweden this has been mitigated by allowing 2 weeks for pharmacists to dispense left-over stock from the previous period's winning bid.42 There are concerns that choosing medicines only on the basis of lowest price will drive local manufacturers out of the market in favour of imports from low-cost countries such as India.22,58 However, the current system provides high retail prices for local and foreign manufacturers alike the acquisition price is heavily discounted, and all companies use globalised supply chains.21

In Spain, the Andalusian regional government set up centralised tendering between 2007 and 2019, with estimated savings of €540 million.59 Nevertheless, the scheme had some weaknesses.18,60 The long duration of the contracts (2 years) and winner-take-all exclusivity could drive competitors out of the market. Some winning bidders were not able (or willing) to meet the commitment to supply the quantity agreed and walked away from the contract, leaving the health service without a reserve supplier.11

Evidence from Sweden has estimated that 10-20% of patients oppose substitution and pay out-of-pocket for another brand.35,55 This suggests that generics and more expensive brands can coexist in the market, while most patients are price -elastic in demand and this should encourage generic diffusion by price competition.

The exchange groups regulate which medicines can be substituted for another by the pharmacist, and thereby constitute miniature markets within which similar products can compete. Spain only allows substitution between products that are identical in almost every respect (active ingredient, mode of administration, dose, pack size and pharmaceutical form). The groups are defined more loosely in Sweden, allowing products to differ in pack sizes and pharmaceutical form (where considered therapeutically equivalent by the regulator). Allowing some product differentiation permits brands with different prices to coexist in the market and encourages galenic innovation. Allowing medicines with the same dose but different pack sizes (e.g. 28 units and 30 units) to coexist potentially increases options for prescribers, promotes competition and avoids wastage.

The “official” profit margin for pharmacies is regulated,14,42 and privately negotiated discounts with manufacturers are disallowed in Sweden42 or strictly limited in Spain.14 The experience in Spain16,23 and elsewhere4,30 show that these restrictions can be circumvented. The incentive to game the system seems weaker in Sweden as manufacturers can compete in price through the monthly tender, price reductions can be reversed if market conditions change, and established brands and galenic innovators can compete by product differentiation with no additional cost to the public payer.55 The margin for dispensing prescription drugs in Spain increases with the ex-factory price on a sliding scale up to a cap. There are documented cases of pharmacies steering patients towards a more expensive product when there are price differences.25,44 To avoid this potential conflict of interest, as part of the reform in 2009-10 in Sweden, the regulated margin was modified to pay a fixed element of 10 SEK (€0.89) per prescription as well as a variable element. The fixed element meant overall profitability of pharmacies was unaffected by the reform, and weakened the incentive to recommend a higher price product.29

There are several limitations to this study. The experiences of other countries may not be generalizable to Spain. The population in Sweden is 10.5 million, about one-quarter of Spain. Medicines packaged for distribution in Sweden can be sold in other Nordic countries, which facilitates parallel imports. One third of pharmacies are publicly owned in Sweden.29 The performance of the off-patent market depends on many actors, private and public.61 Low prices are a cause of shortages.5,6 However, low prices can be the result of excessive regulation, especially the obligation for prices to always fall.62 A free market can be self-correcting: prices are likely to fall when there are many competitors and increase if there are few competitors.5 The tendering system should grant non- exclusive contracts to mitigate risks of stock-outs.7,18 Incumbents sometimes use anti-competitive practices to block generic entry,63 confuse,64 collude,55 undercut competitors, or price-gouge.12,13 Regulators must vigilantly monitor the market and sanction anti-competitive behaviour.65 Strategic medicines can be financed by a separate mechanism.66

Policy makers in Spain have signalled that a fundamental reform of the system for financing off-patent medicines is a strategic priority.15,50,66 The details are very important. This paper offers precise insights on how a reformed system could be configured that could be of interest to lawmakers drafting these reforms. The recommendations can be summarised as 1) allow price differences between medicines, and allow manufacturers to increase prices as well as reduce them, within limits, 2) set a tendering process that requires manufacturers to actively notify their price to the regulator at regular intervals, select medicines based on lowest prices and ability to supply the market, and appoint reserve products, 3) encourage patient choice with appropriate information, 4) modify the architecture of the exchange groups to allow some differences in pack size and possibly pharmaceutical form, 5) carefully design incentives for pharmacies that are based on the services rendered and for dispensing the lowest priced medicine, rather than the value of the medicine, and 6) the regulator should actively monitor the market for cartels, pricing below cost, and risks of shortages.

The market for prescription drugs in retail pharmacies is highly regulated in Spain. Retail price competition is rare, but pharmacies and manufacturers negotiate discounts in the wholesale market.

What does this study add to the literature?It offers a comparison of prices between the Spanish system and other countries, the factors that determine price competition, and a detailed comparison between the Swedish and Spanish systems.

What are the implications of the results?Health policy makers in Spain have published their intention to reform the regulation of the market for off-patent medicines to promote competition for the benefit of patients and the public health system. The comparison with Sweden provides decision-makers with a possible model for achieving this objective. This includes, within limits, freedom of prices, differentiation of products by non-clinical characteristics, and patient choice.

D. Epstein is the sole author of the article.

AcknowledgementsThe author would like to thank Félix Lobo Aleu, Jaume Puig, Guillem López Casanovas, Vicente Ortún, Jenny Carlsson, Catarina Bernett, Carlos Martín Saborido, César Hernández García, Jaime Espín, Gemma Pérez López and Manuel Correa Gómez, and researchers at the Centre for Research in Economics and Health. All errors are the author's.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.