The 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health

Más datosTo identify factors related to the stress levels among pregnant women in Indonesia.

MethodThe study was used cross sectional design. The participants were 92 pregnant women who worked at a footwear manufacturer at Banten, Indonesia. Half of the participants worked less than 40h per week and the other half worked 40h or more per week. A test instrument to measure stress in pregnant women was developed and conducted in this study. Dependent and independent factors were analyzed by the chi-square test.

ResultsOur results showed that 59.78% of respondents had their gestational age was more than 31 weeks; 53.00% of workers experienced moderate stress; and as many 53.26% of respondents experienced a high workload.

ConclusionsOur conclusion confirmed gestational age, workload, and working time related with work stress level of pregnant women significantly.

Pregnant women stress plays an important role in maternal and fetal conditions. Moreover, it is necessary to prevent the possible reactions that come from the stressors confronting pregnant women in their everyday life including their working situation. Only if the possible factors relating to the stress level of pregnant working women are discovered, then the possible strategies and methods can be derived against the effects of the stressors.1 Otherwise, it is important to investigate the stress factors among working women with pregnancy from other socio-cultural backgrounds, so that future research in this area can achieve a more holistic view of the phenomenon of pregnancy and work stress crossing the socio-economic aspects.2

WHO in 2019 calculated that the global Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) in 2017 is at 211 per 100000 live births [with uncertainty interval from 199 to 234). In fact, the MRR in East Asia and the Pacific in 2017 was 69 per 100000 live births. Despite that, MMRs in each country could be different due to how people read the statistical data.3 For instance, the MMR in Indonesia in 2017 was at 177 per 100000 live births.4 If this circumstance was observed on the regional level, then - for instance - Banten Province had MMR at 240 per 100000 live births in 2016.5 The Public Health Office of Banten Province claimed, that one of the reasons for the high MMR in Banten was the social economic issues. Based on the Banten Province Statistics Agency in 2018, around 2.87 million people worked as laborers, and 50.7% of them were women.5,6 All those social economic adversities were the motivation and interest of this study to investigate the factors relating to work stress levels in pregnant working women.

MethodStudy designCross sectional study design was used to prove the hypothesis of this study for investigating the assumed relation between perceived pregnancy-related work stress level as an outcome variable and the intrapersonal character of pregnant mother as well as the working conditions as an exposure variable. Ninety two pregnant women working at an athletic and casual footwear manufacturer in Banten – Indonesia participated in this study. Half of the participants worked less than 40h per week and the other half worked 40h or more per week.

MeasurementWork stress was recorded through the questionnaire for work stress during pregnancy. A valid and reliable test instrument to measure stress in pregnant women was developed and conducted in this study. The participants were grouped regarding their score in the questionnaire for work stress during pregnancy, namely: low work stress level, moderate stress work level, and high work stress level. Questions regarding risk age for pregnant, gestational age, workload level. Every respondent could choose the right answer regarding the age (“20–35 years old” or “≤19 or ≥35 years old”), the gestational age (“≤31 weeks” or “≥31 weeks”). The workload level was measured by questionnaire for workload and consisted of four questions. The workload level was defined as a low workload and high workload. The procedure in the questionnaire was that all participants filled out the informed consent. Ethical research was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitas Nasional, Indonesia. For ethical research, the anonymity of participants was conducted for the protection and confidence of the data.

Statistical analysisA chi-square test was conducted to investigate the relations between age, gestational age, workload, working hours, and work stress. For the inference statistic, the α level was set at below .05. The parameter used in this study was Yates's correction for continuity (χYates2) due to one degree of freedom from the sample and 2×2 cross table-related analysis plan.7 The odds ratio (OR) was provided in this research to forecast how big the risk was that the low work stress level in the relation to moderate work stress level experienced by pregnant working women regarding their intrapersonal characters and work conditions.8 All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Version 23.

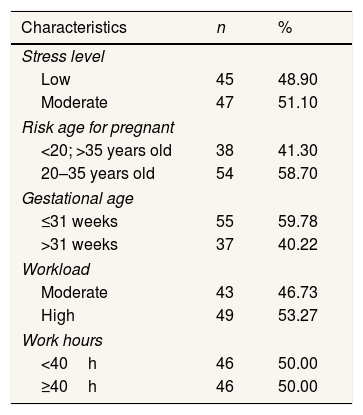

ResultsCharacteristics of participantsData shows the characteristics and frequency of stress level, risk age for pregnant, gestational age, workload, and work hours of the participants (Table 1).

Characteristic and frequencies (N=92).

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Stress level | ||

| Low | 45 | 48.90 |

| Moderate | 47 | 51.10 |

| Risk age for pregnant | ||

| <20; >35 years old | 38 | 41.30 |

| 20–35 years old | 54 | 58.70 |

| Gestational age | ||

| ≤31 weeks | 55 | 59.78 |

| >31 weeks | 37 | 40.22 |

| Workload | ||

| Moderate | 43 | 46.73 |

| High | 49 | 53.27 |

| Work hours | ||

| <40h | 46 | 50.00 |

| ≥40h | 46 | 50.00 |

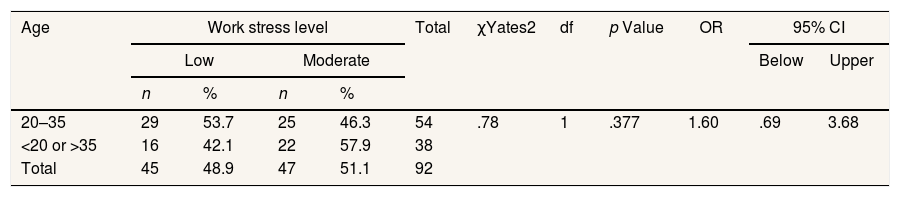

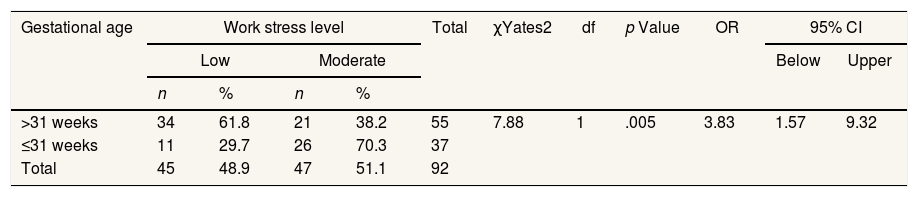

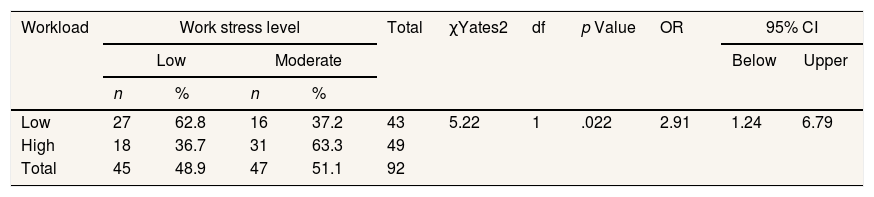

Data for correlations between work stress level as a dependent factor with age risk for pregnant, gestational age, workload and work hours as independent factors show in Tables 2–5.

Correlation between gestational age and work stress level (N=92).

| Gestational age | Work stress level | Total | χYates2 | df | p Value | OR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | Below | Upper | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||||||

| >31 weeks | 34 | 61.8 | 21 | 38.2 | 55 | 7.88 | 1 | .005 | 3.83 | 1.57 | 9.32 |

| ≤31 weeks | 11 | 29.7 | 26 | 70.3 | 37 | ||||||

| Total | 45 | 48.9 | 47 | 51.1 | 92 | ||||||

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

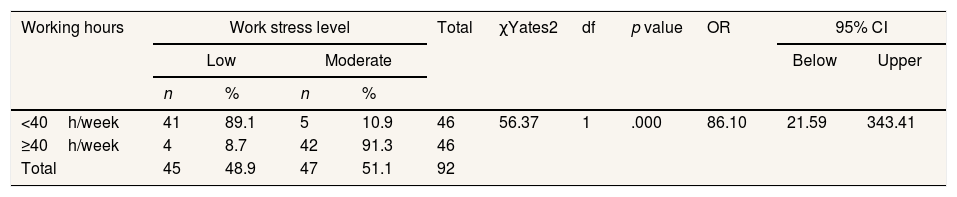

Correlation between working hours and work stress (N=92).

| Working hours | Work stress level | Total | χYates2 | df | p value | OR | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | Below | Upper | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||||||

| <40h/week | 41 | 89.1 | 5 | 10.9 | 46 | 56.37 | 1 | .000 | 86.10 | 21.59 | 343.41 |

| ≥40h/week | 4 | 8.7 | 42 | 91.3 | 46 | ||||||

| Total | 45 | 48.9 | 47 | 51.1 | 92 | ||||||

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Table 2 showed the results of the chi-square test. The analysis showed that the correlation between stress level and risk age for pregnant could not support the assumption of the relationship between risk age for pregnant and work stress level in pregnant working women (χYates2 = .78, df=1, p=.38).

The analysis result of the assumption of relationships between gestational age with work stress levels in pregnant women was significantly granted (χYates2 = 7.88, df=1, p<.01). The further analysis showed the OR was 3.83. It meant that gestational age ≤31 weeks had 3.83 times higher risk of being a moderate work stress level, compared to pregnant women with a gestation of more than 31 weeks (Table 3).

The analysis result of the assumption of relationships between workload and work stress levels in pregnant women (χYates2 = 5.22, df=1, p<.05). The further analysis showed the OR was 2.91. It meant that pregnant women with high workload had 2.91 times higher risk of being a moderate work stress level, compared to pregnant women with low workload (Table 4).

The analysis result of the assumption of relationships between workload and work stress levels in pregnant women (χYates2 = 56.37, df=1, p<.001). The further analysis showed the OR was 86.10. It meant that pregnant women who worked for 40h or more per week had 86.10 times higher risk of being a moderate work stress level, compared to pregnant women who worked for less than 40h (Table 5).

DiscussionThis study could not confirm the assumed association between age and work stress levels during pregnancy. The postulates the lack of association between age and stress experienced by pregnant women.9 This finding may correspond with the meta-analytic finding from the report of the partly lack of relation between age and work-related stress.10 Although the study had not included the specified pregnant women, there was an indication that age was associated with work stress by the moderation of gender.10 The average response to stress increased with the increased age.11 On the other side, older workers perceived slightly more work stress than the younger once, which this study showed the opposite. However, their study did not put pregnant women in the center of investigation.12

Otherwise, the finding in this study has been still leaving the question regarding the propositional reproductive age as postulated, that age between 20 and 35 years old was the good and safe age interval to give birth.13 U-curve of pregnancy-related stress could be one of the reasons why age did not appear to have any association with the work stress.14 So, the effect of age to stress development and pregnancy-related stress could not be differentiated during pregnancy.

Moreover, the assumed correlation between gestational age and work stress level was supported in this study. Increasing gestational age was associated with advancing pregnancy-related stress and anxiety. Maternal prenatal stress developed along with U pattern, in which the stress level of pregnant women high in the first trimester and became lower in the second trimester and reached a high level again in their third trimester.15 Consequently, the risk of delivering a birth a small-for-gestational-age infant was in accordance with the increasing work stress found in pregnant women.16 A similar result informing the association between work stress and small-for-gestational-age.17

The assumed association between workload and work stress levels was granted in this study. According to the effort-reward-imbalance (ERI) model, “the lack of reciprocity between effort spent a reward received in work elicits sustained reactions in the autonomic nervous and endocrine systems”.18 Workload in the term of ERI appeared to be associated with the perceived maternal prenatal work stress.

The result showed that working hours correlated with work stress levels perceived by pregnant women significantly. The OR was 86.10. It was very high compared to the OR results of other factors. The length of working hours can influence the stress level of employees because working generally demands on cognitive, emotional, and physical resources.19 On the cognitive level, working hours more than eight hours per day was associated with decreased attentiveness function.20 The alertness is reduced in relation to increasing working hours.21 Decreased attentiveness function and reduced alertness can not only reduce employee productivity but also was associated with an accident at work.22 Working in excessive periods could also reduce mental health like burnout19 or depression.23 For the pregnant women the increased risk of cardiovascular diseases influenced by stress made by longtime working hours can be also very relevant to protect the maternal and fetal health.24

ConclusionsOur result confirmed that gestational age, workload, and working hours are related to the work stress level of pregnant women significantly.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health (ICOS-PH 2020). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.