To compare, from an empirical point of view, the use of focus group and photovoice as we conducted two studies on food environment in neighbourhoods with different socio-economic profiles.

MethodThe European project Heart Healthy Hoods studied the association between the physical and social environment of Madrid (Spain) and the cardiovascular health of its residents. Two ancillary studies were developed to further expand the study of urban health inequalities using focus group and photovoice. Both studies, similar in their objectives and study populations, are the basis for comparing both techniques. The comparison considered the following methodological aspects: study design, logistic aspects, commitment and involvement, ethical issues, and data analysis.

ResultsWe identified differences, similarities, potentialities, and limitations of each technique with their corresponding results. We found that depending on the research objectives, one technique was more beneficial than the other. If the objective is producing new knowledge, using focus group would be the most appropriate technique, whereas if the objective includes generating social change, photovoice would be more suitable. We found that photovoice is a powerful technique in public health, especially studying social processes related to population health, requiring extra effort from researchers and a special care with the related ethical considerations.

ConclusionsIncreasing participants’ awareness, involving decision makers to channel proposals, the atypical role of researchers and ethical implications of photography are aspects to be considered when choosing photovoice instead of focus group.

Comparar empíricamente el uso del grupo focal y el fotovoz en investigación sobre el entorno alimentario en barrios con diferente perfil socioeconómico.

MétodoEl proyecto europeo Heart Healthy Hoods estudió la asociación entre el entorno físico y social de Madrid y la salud cardiovascular de sus residentes. Dentro de él se desarrollaron dos estudios para analizar las desigualdades en salud utilizando las técnicas del grupo focal y el fotovoz. Ambos estudios, similares en sus objetivos y población diana, fueron la base para comparar las dos técnicas. Consideramos los siguientes aspectos metodológicos: diseño, aspectos logísticos, compromiso e implicación del equipo investigador y de las personas participantes, cuestiones éticas y análisis de los datos.

ResultadosIdentificamos diferencias, similitudes, potencialidades y limitaciones de cada técnica utilizada con sus correspondientes resultados. Dependiendo de los objetivos, una técnica sería más beneficiosa que la otra. Si el objetivo es producir nuevo conocimiento, el grupo focal sería la técnica más adecuada, mientras que, si el objetivo incluye generar cambio social, el fotovoz sería más apropiado. Consideramos el fotovoz una técnica muy provechosa para la investigación en salud pública, especialmente para estudiar procesos sociales en relación con la salud de la población, aunque requiere un esfuerzo adicional por parte del equipo investigador y de los participantes, y un cuidado especial con las consideraciones éticas.

ConclusionesAumentar la conciencia de las personas participantes, involucrar a decisores políticos para canalizar las propuestas resultantes, el papel atípico del equipo investigador y las implicaciones éticas de la fotografía son aspectos a considerar si elegimos el fotovoz frente al grupo focal.

The application of qualitative research in public health has produced very important insights, especially in the field of social determinants of health. The most common qualitative health research techniques are semi-structured interview and focus group (FG).1 Otherwise, different approaches using visual methods like photo-elicitation or photovoice have been successful in studying health issues.2 Considering these advances in the application of qualitative techniques and their scope, we propose a comparison of two group techniques such as FG and photovoice in public health research.

FG was originated in sociology by Merton and Kendall.3 It consists of a formal meeting of 5-10 people selected for being representative of a population group with similar characteristics or experiences. It is used to deeply understand the point of view of the subjects involved in a phenomenon of study and how the collective discourses related to a particular theme, are socially shared and co-constructed.4

FG research has reported relevant results in the study of factors influencing food habits in diverse population groups5 as well as in other urban health topics, like air pollution or alcohol environment.6

On the other hand, photovoice is a relatively new technique. It uses photography to study participants’ perspectives considering their opinions as the main actors of a particular problem. Recently, the inclusion of the perspective of people participating in qualitative studies is taking steps towards their participation not only as subjects-objects of study, but also considering their capacity of originating changes. This approach is also classified within citizen science7 and is usually framed under the umbrella of participatory action research.8 It was first formulated by Wang and Burris,9 who developed it for studying life and health conditions of women in rural China. It consists in putting cameras in participants’ hands and using the photographs they take with their narratives, to evaluate community resources, while stimulating critical reflection and social action.

The objective of this article was to compare, from an empirical point of view, the use of FG and photovoice as techniques for health research. Our goal was to identify differences, similarities, potentialities, and limitations of each technique through the analysis of two studies with the same object of study.

MethodContextThe European project Heart Healthy Hoodsstudied the association between the physical and social environment of the city of Madrid (Spain) and the cardiovascular health of its residents.10 Two ancillary studies were funded to further expand the study of urban health inequalities using FG and photovoice, respectively. These two studies, very similar in their objectives and study population, are the basis for making the comparison of the two techniques used.

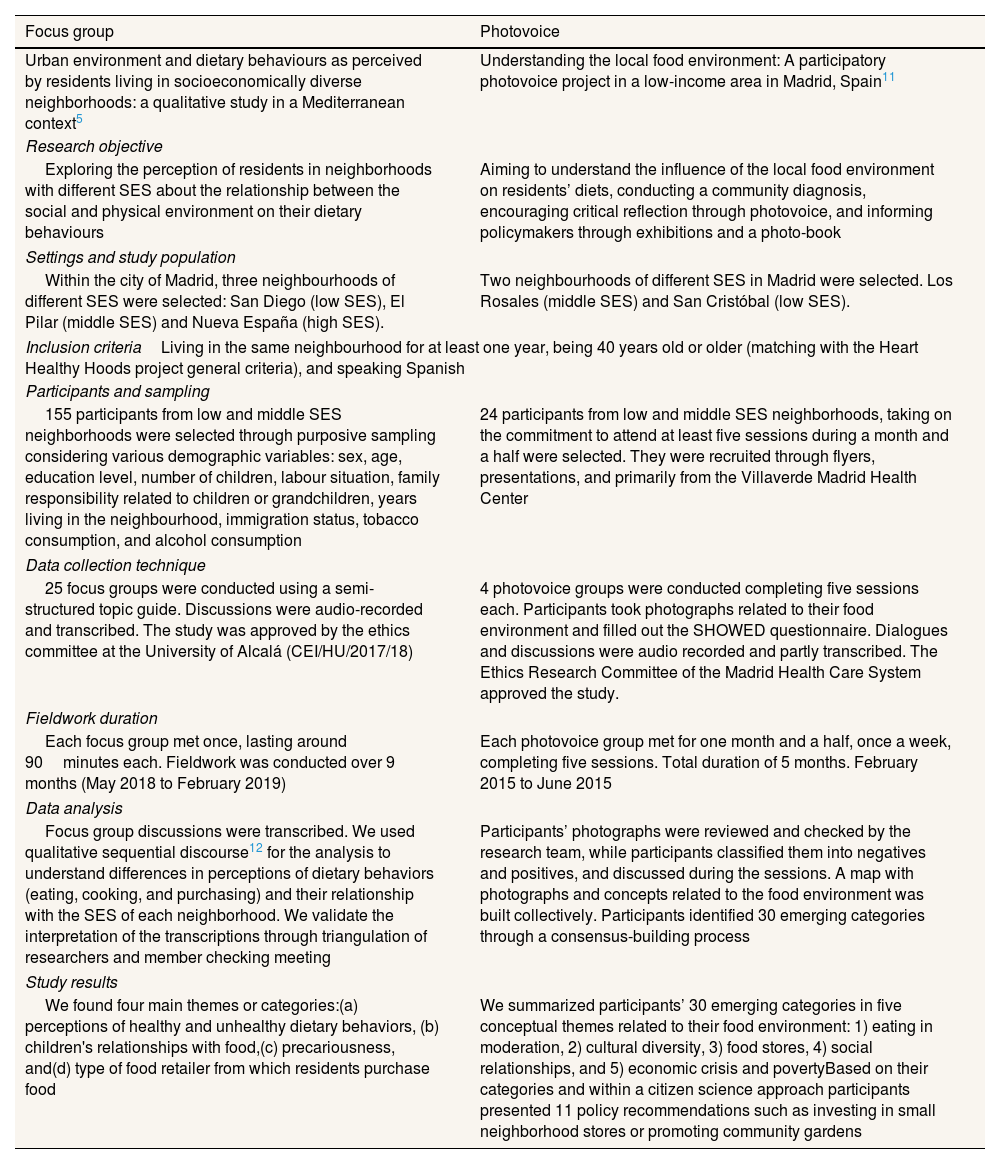

Study designs, settings, participants, field works and resultsIn Table 1 we briefly describe each study.

Heart Healthy Hoods studies using focus group and photovoice.

| Focus group | Photovoice |

|---|---|

| Urban environment and dietary behaviours as perceived by residents living in socioeconomically diverse neighborhoods: a qualitative study in a Mediterranean context5 | Understanding the local food environment: A participatory photovoice project in a low-income area in Madrid, Spain11 |

| Research objective | |

| Exploring the perception of residents in neighborhoods with different SES about the relationship between the social and physical environment on their dietary behaviours | Aiming to understand the influence of the local food environment on residents’ diets, conducting a community diagnosis, encouraging critical reflection through photovoice, and informing policymakers through exhibitions and a photo-book |

| Settings and study population | |

| Within the city of Madrid, three neighbourhoods of different SES were selected: San Diego (low SES), El Pilar (middle SES) and Nueva España (high SES). | Two neighbourhoods of different SES in Madrid were selected. Los Rosales (middle SES) and San Cristóbal (low SES). |

| Inclusion criteriaLiving in the same neighbourhood for at least one year, being 40 years old or older (matching with the Heart Healthy Hoods project general criteria), and speaking Spanish | |

| Participants and sampling | |

| 155 participants from low and middle SES neighborhoods were selected through purposive sampling considering various demographic variables: sex, age, education level, number of children, labour situation, family responsibility related to children or grandchildren, years living in the neighbourhood, immigration status, tobacco consumption, and alcohol consumption | 24 participants from low and middle SES neighborhoods, taking on the commitment to attend at least five sessions during a month and a half were selected. They were recruited through flyers, presentations, and primarily from the Villaverde Madrid Health Center |

| Data collection technique | |

| 25 focus groups were conducted using a semi-structured topic guide. Discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed. The study was approved by the ethics committee at the University of Alcalá (CEI/HU/2017/18) | 4 photovoice groups were conducted completing five sessions each. Participants took photographs related to their food environment and filled out the SHOWED questionnaire. Dialogues and discussions were audio recorded and partly transcribed. The Ethics Research Committee of the Madrid Health Care System approved the study. |

| Fieldwork duration | |

| Each focus group met once, lasting around 90minutes each. Fieldwork was conducted over 9 months (May 2018 to February 2019) | Each photovoice group met for one month and a half, once a week, completing five sessions. Total duration of 5 months. February 2015 to June 2015 |

| Data analysis | |

| Focus group discussions were transcribed. We used qualitative sequential discourse12 for the analysis to understand differences in perceptions of dietary behaviors (eating, cooking, and purchasing) and their relationship with the SES of each neighborhood. We validate the interpretation of the transcriptions through triangulation of researchers and member checking meeting | Participants’ photographs were reviewed and checked by the research team, while participants classified them into negatives and positives, and discussed during the sessions. A map with photographs and concepts related to the food environment was built collectively. Participants identified 30 emerging categories through a consensus-building process |

| Study results | |

| We found four main themes or categories:(a) perceptions of healthy and unhealthy dietary behaviors, (b) children's relationships with food,(c) precariousness, and(d) type of food retailer from which residents purchase food | We summarized participants’ 30 emerging categories in five conceptual themes related to their food environment: 1) eating in moderation, 2) cultural diversity, 3) food stores, 4) social relationships, and 5) economic crisis and povertyBased on their categories and within a citizen science approach participants presented 11 policy recommendations such as investing in small neighborhood stores or promoting community gardens |

SES: socioeconomic status.

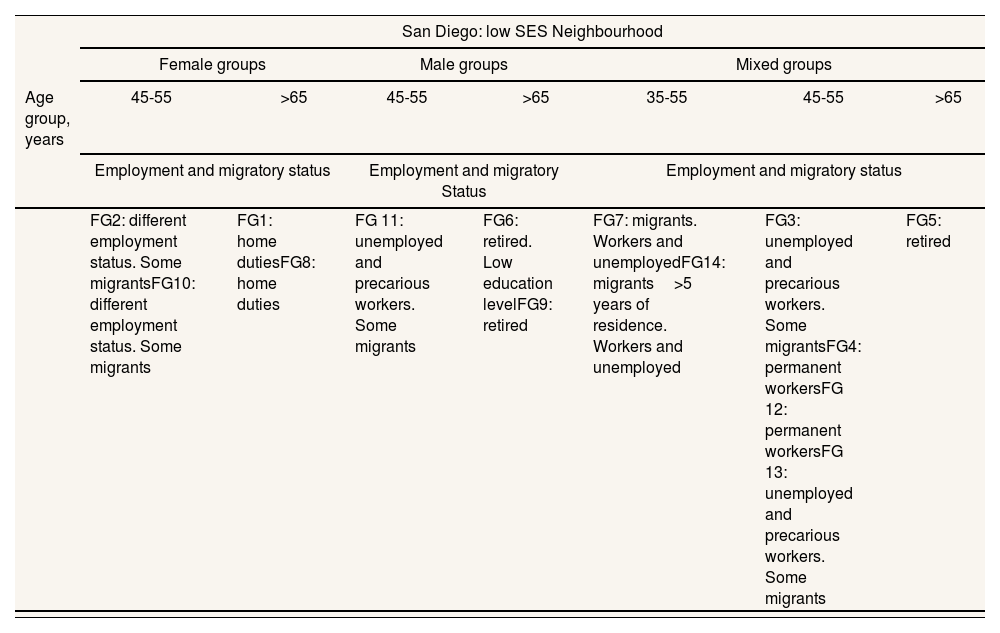

According to the socioeconomic status (SES) of the study areas and the variables of interest before mention, we conducted 14 FG in the low SES neighbourhood, and 11 FG in the middle SES neighbourhood (Table 2).

Number and social composition of focus groups.

| San Diego: low SES Neighbourhood | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female groups | Male groups | Mixed groups | |||||

| Age group, years | 45-55 | >65 | 45-55 | >65 | 35-55 | 45-55 | >65 |

| Employment and migratory status | Employment and migratory Status | Employment and migratory status | |||||

| FG2: different employment status. Some migrantsFG10: different employment status. Some migrants | FG1: home dutiesFG8: home duties | FG 11: unemployed and precarious workers. Some migrants | FG6: retired. Low education levelFG9: retired | FG7: migrants. Workers and unemployedFG14: migrants>5 years of residence. Workers and unemployed | FG3: unemployed and precarious workers. Some migrantsFG4: permanent workersFG 12: permanent workersFG 13: unemployed and precarious workers. Some migrants | FG5: retired | |

| El Pilar: middle SES neighbourhood | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female groups | Male groups | Mixed groups | |||||

| Age group, years | 45-55 | >65 | 45-55 | >65 | 35-55 | 45-55 | >65 |

| Employment and migratory status | Employment and migratory Status | Employment and migratory status | |||||

| FG15: home dutiesFG21: home duties | FG22: retired | FG20: migrants>5 years living in SpainMigrantsUnemployed and workersFG25: migrants>5 years living in SpainUnemployed and workers | FG16: different family compositionFG17: unemployed and precarious workersFG18: permanent workersFG23: permanent workersFG24: unemployed and precarious workers | FG19: retired | |||

FG: focus group; SES: socioeconomic status.

We started each FG with a briefing about the objective of the study (i.e., we like to know how living in your neighbourhood is related to health) to not condition excessively the discourse of participants. Although we wanted the topics of interest to emerge spontaneously, the research team designed a semi-structured topic guide to be followed in all FG (see online Appendix A). In doing so we considered a few different aspects related to urban health, like food environment, physical activity, tobacco, alcohol consumption as well as perception of public services. As we conducted the FG, when we felt information was becoming repetitive and no new core themes or issues were mentioned, we determined we had reached data saturation and concluded the FG. The qualitative sequential discourse method we used consists in identifying categories and applying them to the data. Researchers read all the transcripts and made a list of codes, subcategories, and categories, highlighting all main categories in the text. These categories sometimes matched with core topics previously determined by the researchers, such as the use of big supermarkets to purchase food. We grouped refined categories into broader themes to detect conceptual similarities, refine differences between categories, and discover discursive patterns.

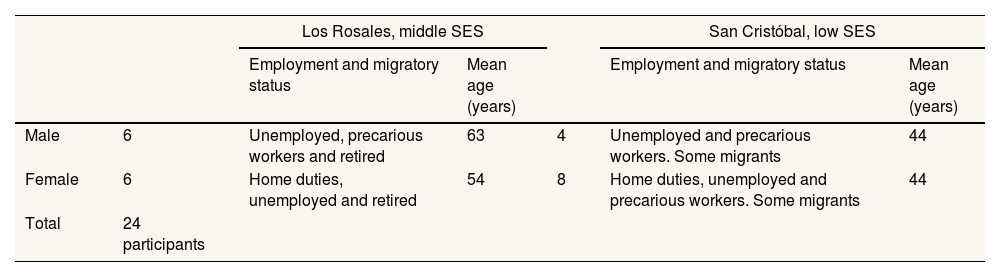

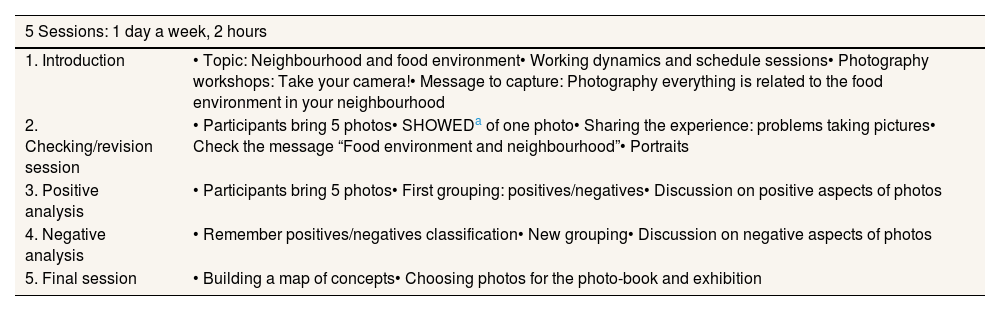

Photovoice study of the food environment in VillaverdeTwenty-four men and women in between 40 and 70 years old participated in the study (Table 3). The number of photovoice sessions usually described in literature are in between three and nine.13 According to the study objectives, we decided that five sessions were appropriate. In an introduction session, all participants received information about the study, with a presentation of the objective: the topic of interest (food environment and their neighbourhood) and the importance of engaging citizens in the research. An overview of the five sessions schedule was presented to set a day and time to meet once a week for the next five weeks (Table 4). They also received one hour's workshop on photography covering issues like the use of digital camera but also ethics and safety. Every participant signed an informed consent allowing us to audio and video record every photovoice session, self-images, and taken pictures.

Photovoice participants and groups distribution within neighbourhoods.

| Los Rosales, middle SES | San Cristóbal, low SES | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment and migratory status | Mean age (years) | Employment and migratory status | Mean age (years) | |||

| Male | 6 | Unemployed, precarious workers and retired | 63 | 4 | Unemployed and precarious workers. Some migrants | 44 |

| Female | 6 | Home duties, unemployed and retired | 54 | 8 | Home duties, unemployed and precarious workers. Some migrants | 44 |

| Total | 24 participants | |||||

SES: socioeconomic status.

Photovoice schedule sessions.

| 5 Sessions: 1 day a week, 2 hours | |

|---|---|

| 1. Introduction | • Topic: Neighbourhood and food environment• Working dynamics and schedule sessions• Photography workshops: Take your camera!• Message to capture: Photography everything is related to the food environment in your neighbourhood |

| 2. Checking/revision session | • Participants bring 5 photos• SHOWEDa of one photo• Sharing the experience: problems taking pictures• Check the message “Food environment and neighbourhood”• Portraits |

| 3. Positive analysis | • Participants bring 5 photos• First grouping: positives/negatives• Discussion on positive aspects of photos |

| 4. Negative analysis | • Remember positives/negatives classification• New grouping• Discussion on negative aspects of photos |

| 5. Final session | • Building a map of concepts• Choosing photos for the photo-book and exhibition |

SHOWED is an acronym that groups the following five questions: What do you See here? What is really Happening? How does this relate to Our lives? Why does this problem or Strength exist? What can we Do about it?13.

At the end of the study every participant had to fill at least one SHOWED about their five final photos. Photovoice groups sorted together their photographs into categories, emerging from their photographs and discussions arising from these images. In the final session, groups build a map with photographs and concepts related, that best reflected their neighborhood food environment (see online Appendix B). Among all photographs taken, each participant chose one photo to be presented in the future photo-book and exhibition. Based on their photos and categories they presented 11 policy recommendations to decision makers in a citizen science meeting. Additionally, and as remarkable aspect, two of the participants from photovoice Villaverde collaborated in writing the photobook and one of them collaborated in the photovoice article that we used for this comparison.

Factors of comparisonTwo of the researchers, experts in qualitative research, participated in the field work and analysis of both studies, facilitating and analyzing FG and photovoice sessions. During the field work of the photovoice study, the first author compiled a list of common and different aspects between the techniques, especially the most practical aspects. After carrying out the second study with the FG, this list was completed. This list was shared by the first author with the other researcher who had participated in both techniques, and with another researcher who had participated only in the FG. From that moment on, the comparison was made in a balanced way between empirical aspects and theoretical aspects based on the literature review regarding these two techniques. Finally, we reached a consensus considering the following factors:

- •

Study design: if the objective of the study is purely scientific (to gain new knowledge about a problem) or it pretends to identify an intervention that will improve the life of the study population. Within the design, the number of meetings with participants, as well as the number and type of participants are elements to keep in mind.

- •

Logistic aspects: when choosing a technique, important aspects must be considered such as human resources not included in the research team to carry out some tasks, devices needed like cameras, printers or laptops, food for the meetings, availability of different spaces to hold them, or the previous existence of a social network.

- •

Commitment and involvement: these elements are especially relevant in photovoice technique. Participants must commit to attend and participate in at least five meetings, as well as taking photographs. The research team must commit to transfer the study results to policy makers.

- •

Data analysis: FG data is analysed by researchers, whereas in photovoice participants produce and analyse their own data.

- •

Discourses construction: there are also important differences in the way discourses are elaborated. Discourses obtained from photovoice will be more charged with “emotion” and encouraging the social change than those produced in FG.

- •

Ethical issues: taking and displaying photographs raises data protection and privacy issues, adding complexity to the photovoice technique.

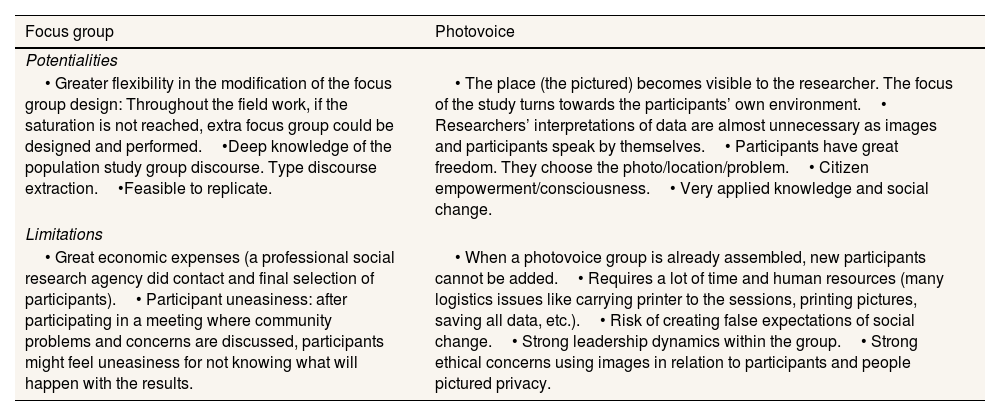

We show key differences and similarities between the two techniques in Table 5, as well as their potentialities and limitations in Table 6.

Differences and similarities of conducting focus group and photovoice techniques.

| Focus group | Photovoice |

|---|---|

| Differences | |

| • Textual data.• 5-10 participants.• 90minutes meeting/session.• Takes place once.• Purposive sampling.• Little directive facilitation.• Participants do not know each other.• Participants may or may not acquire new knowledge.• Researchers do the analysis.Type of food retailers where residents purchase their foodAa: I mean, there were stores everywhere… Of fried potatoes, stores of all kinds, food markets and everything. And now everything has changed. Now there is none of that.JA: Sure. I...A: All that has changed completely. Now there is Mercadona b, it is all full of Chinese stores, new fruit stores…(disappointed)…I mean, on that topic, for me, the whole neighborhood has gotten worse, it's not like in old days. Logically, it will have to change with time, but I liked the way the neighborhood was in the past more than how it is now.JA: …and the old shopkeeper, the one who left you things on credit or...Exactly.JA: That has been lost. (FG11: males 45 to 55 years old, unemployed and precarious job. Low-SES neighbourhood.)AccessibilityL: So, the... the... the sidewalks, the roads are a shame...A: Sure. On the streets, you have to go... (paying attention to not fall).S: The other day I almost crashed myself with a bollard.L: Right.E: Besides, the sidewalks are all lifted, you have to go looking... Well, it's absurd. (FG2: female 45-55 years old. Different degree of family responsibility and labor status. Some immigrants. Low-SES neighbourhood.)PrecariousnessP: At the beginning when I arrived (to Spain) I was quite screwed, I went to Cáritasc. Cáritas was helping me with food. (…) You saw a line of shopping carts of 40 or 50 people waiting for food. But then you saw the gypsies on the corner waiting for the woman with an awesome Mercedes that freaked you out. You said, oh well. What a pity. How sad this is. That's why Cáritas, from what we can see, has already stopped giving food to almost everyone, due to the issue of... of course, everyone went. Anyone went. (FG3: mixed group (male and female) 45-55 years old. Unemployed and precarious workers. Some immigrants. Low-SES neighbourhood.)• Scientific research approach. | • Textual data+photography.• 5-8 participants.• 5 sessions, 2hours each.• Monitoring of 5 weeks-1 year.• Purposive+convenience sampling.• Active and complex facilitation. Facilitator engages with participants concerns.• They could know each other.• They will become experts.• Participants do the analysis.Food storesIn relation to photo of two fishmongers:J: Traditional shopkeepers are the ones that give more confidence, there (at supermarkets) you purchase products randomly, you do not really know…, here (at the neighborhood fishmongers) you deal directly with the vendor, which always inspires trust (…) we have to protect these stores against other retail types especially in terms of places where you can by fresh food.P: They are the fishmonger shop assistants: the joy, the charm and the naturalness that both transmit. (Photovoice male group: middle SES neighbourhood.)Ageing and food accessibilityIn relation to photo of a ramp access to a supermarket:A: If I cannot access, do I have the same opportunities?J: A ramp access with a ridiculous incline and lots of difficulties. Lack of access to fresh food for a large part of the population. There is a lack of public administration interest. We have to demand policy makers to make adequate access. (Photovoice male group: middle SES neighbourhood.)Poverty and crisisIn relation to a photo of a man waiting to get some sardinesJU: He asked me if I could please give him more, that he was in dire need.R: There is a lot of poverty in the neighborhood (…) The association spent an amount money to buy 100 kilos of sardines and sharing with all the neighborhood (…) If people were more supportive, maybe they would not be so hungry either, if we all put a little, I think that this wouldn’t exist. Some people have a very high salary and others have nothing.• (Photovoice female group: low SES neighbourhood.)Research for change approach. |

| Similarities | |

| • Validation or member checking: ideally, besides the ethical commitment of returning data to participants, extra feed-back sessions are needed to validate the results. | • Constant member checking: being a multi-session process reaching a consensus among participants and their messages, the validation with participants is produced constantly. |

FG: focus group; SES: socioeconomic status.

Potentialities and limitations of conducting focus group and photovoice techniques.

| Focus group | Photovoice |

|---|---|

| Potentialities | |

| • Greater flexibility in the modification of the focus group design: Throughout the field work, if the saturation is not reached, extra focus group could be designed and performed.•Deep knowledge of the population study group discourse. Type discourse extraction.•Feasible to replicate. | • The place (the pictured) becomes visible to the researcher. The focus of the study turns towards the participants’ own environment.• Researchers’ interpretations of data are almost unnecessary as images and participants speak by themselves.• Participants have great freedom. They choose the photo/location/problem.• Citizen empowerment/consciousness.• Very applied knowledge and social change. |

| Limitations | |

| • Great economic expenses (a professional social research agency did contact and final selection of participants).• Participant uneasiness: after participating in a meeting where community problems and concerns are discussed, participants might feel uneasiness for not knowing what will happen with the results. | • When a photovoice group is already assembled, new participants cannot be added.• Requires a lot of time and human resources (many logistics issues like carrying printer to the sessions, printing pictures, saving all data, etc.).• Risk of creating false expectations of social change.• Strong leadership dynamics within the group.• Strong ethical concerns using images in relation to participants and people pictured privacy. |

The aspects included in Table 5 and Table 6 correspond precisely to characteristics previously described in literature that define and differentiate each of the techniques. Related to the differences, we describe two of them; the facilitation and the data analysis.

The facilitation model used for FG or for a photovoice group is quite different. Conducting FG requires moderation tasks only the day of the meeting. In photovoice, facilitators had to monitor/accompany participants for at least one month and a half. The facilitator in photovoice usually gets personally involved in the problem addressed by the group, while in FG the role of the research team in relation to participants is more traditional.

The process of data analysis is different. In FG, researchers work together to interpret the transcripts and in photovoice the analysis is mainly done by participants. In the last session participants also summarize their results by presenting a map of categories and photos (see online Appendix B) as an overview of the findings “constructed” over the five sessions

DiscussionConsidering the purpose of the study was to compare from an empirical perspective, the use of FGs and photovoice as we conducted two studies on food environment in neighbourhoods with different socio-economic profiles, both techniques proved to be very fruitful, providing novel and useful results.5 We cannot state that one technique is better than the other for the study of urban health. In fact, in addition to our work, several studies have used these techniques with equally remarkable results.14 Some of the differences showed in the results, had already been described in literature. For example, our approach to moderating FG was framed within the Qualitative School of Madrid15 and other authors,16 in which moderator intervenes little and concentrates on listening and observing. There are no clear rules on how to facilitate photovoice groups.17 In practice, we carried out some of the facilitator functions or skills used in action research,18 such as balancing interventions, giving meaning or encouraging group meaning-making, among others. Related to results, from FG these are drawn from the readings and analyses done by different researchers19 of the literal transcriptions of the FG. We used the qualitative sequential discourse method.12 In photovoice, as Wang and Burris9 propose, participants themselves analyse their photos and debates. Results would be analysed as if it were a qualitative description. Qualitative descriptive studies produced findings closer to the data as given.20 In our photovoice study, several participants in Villaverde wrote proposals for policy recommendations, explained those to decision makers and actively collaborated in the writing of a book and scientific articles.11

Given all of above, we found advantages and difficulties with each technique, which are explained bellow.

The importance of the discourse could be a noteworthy reason to use FG in a study. Discourses gathered through FG allowed us to use different theories for analysis. For example, in our qualitative study, we used grounded theory to analyse the perceived effects of a comprehensive smoke-free law according to the socioeconomic status of neighbourhoods,21 and the qualitative sequential discourse method to understand how the residents’ perceptions of their food environment affect their dietary habits.5 Despite the only analytical purpose in photovoice is giving participants the ability to voice their analysis of the situation, we also found some theoretical analysis conducted after the whole participative and action process, based on the transcripts, photos and/or the processes experienced.22

We consider several key elements when choosing the photovoice technique instead of FG: increasing the critical awareness of participants, involving local or regional decision makers before starting the study, the atypical role of the research team and the implications of using photography. In photovoice, social intervention was not sought, although it was not disdained either. An attempt was made to empower participants so that they were aware of the reality of their neighbourhood and acted accordingly. In this sense, we highlight the relevance that participatory studies with transformative vocation and social intervention could have in the general framework of public health.

FG does not intend to increase the critical awareness or knowledge of the study population. However, according to some authors the mere fact of participating in FG makes participants reflect and acquire new ideas on the research topic. FG are not simply a mean of eliciting knowledge from participants but are often reported to be significantly creative and transformative experiences for them.23

Despite the possibility of increasing critical awareness through FG, the difference with photovoice in this sense is enormous. Our study gave us the opportunity to see how the fact that participants met five times raised awareness about the problem,24 as other photovoice studies have shown.25

Furthermore, sometimes in classic FG, participants do not agree with how researchers have analysed their discourses. In photovoice the results are validated simultaneously during the analysis of participants. In qualitative research, the validation of results, or member checking, is a fundamental step that does not normally occur.26 We consider this type of extra feedback session necessary to listen to participants, making sure they feel represented by the researchers’ interpretations.27

In addition, within FG based research, post-project evaluation is not usually implemented either. We found very few publications regarding the design of specific interventions supported by FG findings.28

Considering the application of both techniques in several evidence-based decision-making studies, like changes in drug prescriptions by general practitioners after participating in a qualitative study28 or generate policy recommendations on alcohol urban environment using photovoice,29 we highlight the potentialities of these techniques as a great input in citizen science.30

As mentioned previously, in photovoice, at the end of the five sessions, results are ready: the concept map, the photos and the SHOWED forms. No further analysis by researchers is required. According to the objectives of the technique, the only thing left to do would be presenting the results publicly informing policy/decision makers. That is, after a month and a half of work, there would be results. While transcribing every FG and then conducting a triangulate analysis can be very time consuming, photovoice requires more dedication during and between sessions.

Another characteristic of the role the research team will play in photovoice is the involvement with local or regional policy makers and the close collaboration with other organizations within the community (non-governmental organizations, neighbourhood associations, community centres, etc.). This collaboration demands great efforts synchronizing agendas, languages, and priorities (for example, the time a researcher concerned with scientific papers is different as those of a social worker focused on the needs of the community).

Photography is a tool only included in photovoice. Although there are FG studies supported by images,31 we cannot make an empirical comparison with the way we designed and conducted our FG study.

Regarding potentialities, using FG we get a deep knowledge of the study population, by extracting the type or expected discourse of that population.32,33 In photovoice, participants provided new knowledge, and also gained social recognition that transformed their self-perception.25 Results could be transformed into recommendations for policymakers related to food.

Related to ethical considerations, informed consent, and release of images (both by the participants and by the people who may appear in the photographs) are essential, but not enough. Special care must be taken with sensitive or marginalized populations.34

Limitations and strengths of the studyComparing both techniques, corresponding theoretical postulates were kept in mind. Nevertheless, the fact of having participated as facilitators in both studies may have introduced certain personal biases when evaluating one technique compared to the other. To reduce this bias, considerations previously described by other authors have been used to define and differentiate each technique more objectively.

The study has strengths like its practical and empirical approach. This comparison of techniques facilitates and supports other researchers who consider the design of one type of study or another beyond what it could be review at a theoretical level about these two techniques. It provides a very pedagogical vision when thinking about and designing a possible study of a participatory or qualitative nature.

ConclusionsThis article should serve as a guide for other qualitative studies planning to use the techniques of photovoice and/or FG.

Depending on the research objectives, one technique may be more beneficial than the other. Both techniques are complementary and may even be used within the same study.

If the research objective is to increase or produce new scientific knowledge within a specific topic, FG would be the most appropriate technique. If the objective includes involving the population to generate changes like acquiring new knowledge and developing awareness of certain troublesome and/or approaching political decision spaces, photovoice would be more suitable.

We found that photovoice is a powerful methodology in the study of physical aspects connected to health or social issues requiring extra effort from researchers and participants. In addition, photovoice requires special care with related ethical considerations.

We found that the effect of participating in FG studies has not been sufficiently assessed. Analyses of possible changes in awareness, self-consciousness and/or behaviour should be included in the design of qualitative research in general, at least when it comes to communities or population groups that are vulnerable or susceptible to such changes.

FG may be the most appropriate technique for producing new scientific knowledge within a specific topic. Photovoice is a participatory action research technique focused on social change that necessarily increases participants’ engagement and awareness, and involves decision makers to channel proposals. The atypical role of photovoice researchers and ethical implications of photography must be considered.

Availability of databases and material for replicationData made available to people who request it by contacting the corresponding author.

New qualitative approaches using photography as a tool for collecting perceptions have shown to be fruitful in public health research, as shown in studies based on photovoice. However, it is worth considering their scope, implications, potentialities, and limitations of these techniques compared to other classic qualitative techniques.

What does this study add to the literature?After developing two studies very similar in terms of objectives and study population, one using photovoice and the other using focus group, we provide a comparison guide for health researchers planning to use these techniques.

What are the implications of the results?Increasing participants’ awareness, involving decision makers to channel proposals, the atypical role of researchers and ethical implications of photography are aspects to be considered when choosing photovoice instead of focus group.

Jorge Marcos Marcos.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsConceptualization: P. Conde. Investigation: P. Conde, J. Rivera-Navarro, M. Gutiérrez-Sastre, I. González-Salgado, M. Franco and M. Sandín Vázquez. Formal analysis: P. Conde, J. Rivera-Navarro and M. Sandín Vázquez. Funding acquisition: J. Rivera-Navarro, M. Franco. Supervision: J. Rivera-Navarro and M. Sandín Vázquez. Writing original draft: P. Conde, J. Rivera-Navarro and M. Sandín Vázquez. Writing, review and editing: P. Conde, J. Rivera-Navarro, M. Gutiérrez-Sastre, I. González-Salgado, M. Franco and M. Sandín Vázquez.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Jorge Barriuso and Ulises Díaz-Ropero for their linguistic assistance on this article, and every person (residents and health workers) who participated and assisted in any of the focus groups or photovoice sessions and meetings.

FundingThis work was funded by Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness [CSO 2016-77257-P] and by the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme [FP7/2007-2013/ERC] Starting Grant Heart Healthy Hoods agreement no. 336893.

Conflicts of interestNone.