This study examines the psychometric properties of the revised Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES-2010) in a context of economic crisis and growing unemployment.

MethodsData correspond to salaried workers with a contract (n=4,750) from the second Psychosocial Work Environment Survey (Spain, 2010). Analyses included acceptability, scale score distributions, Cronbach's alpha coefficient and exploratory factor analysis.

ResultsResponse rates were 80% or above, scores were widely distributed with reductions in floor effects for temporariness among permanent workers and for vulnerability. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were 0.70 or above; exploratory factor analysis confirmed the theoretical allocation of 21 out of 22 items.

ConclusionThe revised version of the EPRES demonstrated good metric properties and improved sensitivity to worker vulnerability and employment instability among permanent workers. Furthermore, it was sensitive to increased levels of precariousness in some dimensions despite decreases in others, demonstrating responsiveness to the context of the economic crisis affecting the Spanish labour market.

Este estudio examina las propiedades psicométricas de la versión revisada de la Escala de Precariedad Laboral (EPRES-2010) en un contexto de crisis económica y creciente desempleo.

MétodosMuestra de personas ocupadas con contrato (n=4750) provenientes de la segunda Encuesta de Riesgos Psicosociales (España, 2010). Se evaluaron la aceptabilidad, la distribución de puntuaciones, la consistencia interna y el análisis factorial exploratorio.

ResultadosLa aceptabilidad estuvo en torno al 80%, con puntuaciones ampliamente distribuidas y una reducción del efecto suelo para «vulnerabilidad» y «temporalidad». La consistencia interna estuvo en torno a 0,70. El análisis factorial confirmó la pertenencia de 21 de 22 ítems a las escalas correspondientes.

ConclusiónLa versión revisada de la EPRES demostró adecuadas propiedades psicométricas y mayor sensibilidad para medir la vulnerabilidad, así como la inestabilidad laboral en personas con contrato permanente. Además, fue sensible a incrementos de la precariedad en algunas dimensiones, a pesar de su disminución en otras, demostrando sensibilidad a los profundos cambios ocurridos en el mercado laboral español.

The Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES), developed by researchers from the Health Inequalities Research Group - Employment Conditions Network (GREDS-EMCONET),1,2 was first validated in Spain with 2004-05 data, demonstrating good psychometric properties and construct validity,3 with subsequent applications in epidemiologic studies further reinforcing its construct validity.4

A revised version of the EPRES (hereafter EPRES-2010 for clarity), with changes aimed at overcoming limitations identified in the previous validation study,3 was included in the 2010 edition of the Psychosocial Work Environment Survey, a population-based survey conducted by the Spanish Union Institute of Work, Environment and Health (ISTAS).5

This revised version of the questionnaire (EPRES-2010) was applied in 2010, in the context of the highest unemployment rate (20%) seen in Spain since 1997, after which unemployment continued rising steeply, reaching 27% by the first trimester of 2012 and exceeding the highest unemployment rates observed since 1975.6 The importance of this lies in the fact that precarious employment is understood to be tightly linked to the unemployment rate: high unemployment rates reduce workers’ bargaining power and capacity to refuse poor employment and working conditions, thus increasing the precariousness of employment overall.

Thus, this study serves the double purpose of assessing the psychometric properties of the revised version of the EPRES (EPRES-2010) and, by doing so in a context of high unemployment, assessing its suitability for use under adverse labour market circumstances.

MethodsSampleThe Psychosocial Work Environment Survey was conducted on nationally representative sample of workers, which for this study was restricted to salaried workers with a contract (n=4,750). The survey protocol was approved by the Spanish Union Institute of Work, Environment and Health (ISTAS) Research Committee.

The revised Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES-2010)The EPRES is a six-dimensional scale, including ‘temporariness’, ‘disempowerment’, ‘vulnerability’, ‘wages’, ‘rights’, and ‘exercise rights’. In the development of the revised EPRES-2010 version, changes were performed on the questionnaire based on previous validation results (see Online supplementary material).3 Significant changes (three subscales) included: changing one item in ‘temporariness’ to improve the assessment of instability among permanent workers and reduce floor effects; reducing one item and increasing response categories in ‘disempowerment’; rewording of the items in ‘vulnerability’ to limit the subjective appraisal of experiences of defencelessness and avoid double barrelled questions, in order to reduce floor effects. Minor changes (three subscales) included: homogenizing the number of response categories in ‘wages’ items; reducing the number of items in ‘rights’ in order to reduce questionnaire length and overlap with ‘exercise rights’; adding one item in ‘exercise rights’ to distinguish between getting a day off for personal reasons or family affairs. Scale management followed the same steps as for the first version of the questionnaire.3

AnalysisAcceptability (proportion of subjects with at least one missing item), means and standard deviations, observed score ranges, and floor and ceiling effects (proportion of subjects with lowest and highest possible scores) were assessed separately for temporary and permanent workers. We assessed reliability with Cronbach's alpha coefficient, and the placement of items into subscales with principal axis exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. We calculated frequency distributions for individual items and item-scale and inter-scale Pearson correlations (available upon demand). Analyses were performed using SPSS v 19.0 for Windows.

ResultsStudy subjects (n=4,750) are in greater proportion male (56.2%), aged 30 to 49 years (56.9%), have complete primary (30.6%) or secondary education (24.5%), work in commerce (16.8%) and manufacturing (12.2%), hold permanent contracts (75.9%), and report tenures greater than 5 years (48.2%).

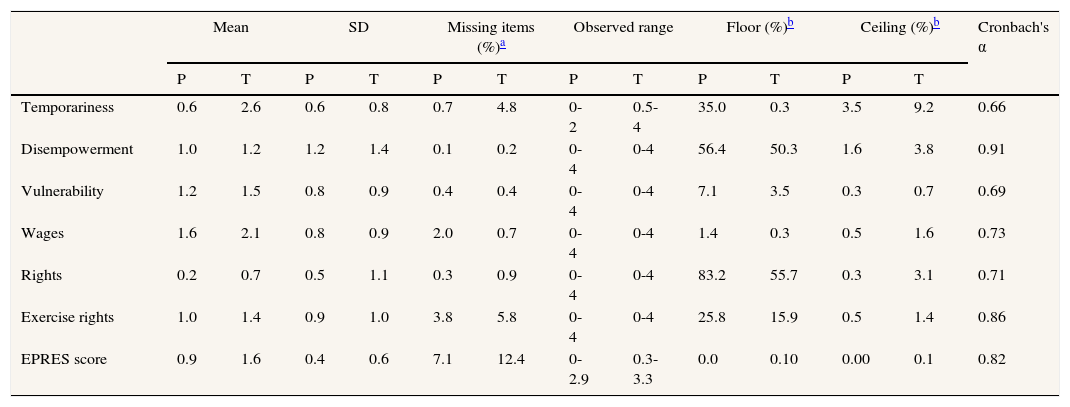

All item response categories were used. The proportion of missing items was low, although somewhat higher for temporary than permanent workers. Means for ‘disempowerment’, ‘vulnerability’ and ‘exercise rights’ were roughly around 1, but lower for ‘rights’ and for ‘temporariness’ among permanent workers, and higher for ‘wages’ and for ‘temporariness’ among temporary workers. Standard deviations were roughly around 1, with few exceptions.

With the exception of ‘temporariness’, subscale score ranges coincided with the theoretical 0-4 range. Percentages of ceiling effects were low, but floor effects were high for ‘rights’ and ‘disempowerment’, and for ‘temporariness’ among permanent workers. Subscale reliability coefficients were all at or above 0.7. The global score ranged from 0 to 3.3, had neither floor nor ceiling effects, and a reliability coefficient of 0.82 (Table 1).

Scale descriptive statistics: mean, standard deviation (SD), missing items, range, floor and ceiling effects, and Cronbach's alpha coefficient of the Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES-2010). Salaried workers, PWES survey, Spain, 2010.

| Mean | SD | Missing items (%)a | Observed range | Floor (%)b | Ceiling (%)b | Cronbach's α | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | T | P | T | P | T | P | T | P | T | P | T | ||

| Temporariness | 0.6 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 4.8 | 0-2 | 0.5-4 | 35.0 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 9.2 | 0.66 |

| Disempowerment | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0-4 | 0-4 | 56.4 | 50.3 | 1.6 | 3.8 | 0.91 |

| Vulnerability | 1.2 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0-4 | 0-4 | 7.1 | 3.5 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.69 |

| Wages | 1.6 | 2.1 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0-4 | 0-4 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 1.6 | 0.73 |

| Rights | 0.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0-4 | 0-4 | 83.2 | 55.7 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 0.71 |

| Exercise rights | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 3.8 | 5.8 | 0-4 | 0-4 | 25.8 | 15.9 | 0.5 | 1.4 | 0.86 |

| EPRES score | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 7.1 | 12.4 | 0-2.9 | 0.3-3.3 | 0.0 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.1 | 0.82 |

EPRES: Employment Precariousness Scale; P: permanent; T: temporary; SD: standard deviation; PWES: Psychosocial Work Environment Survey.

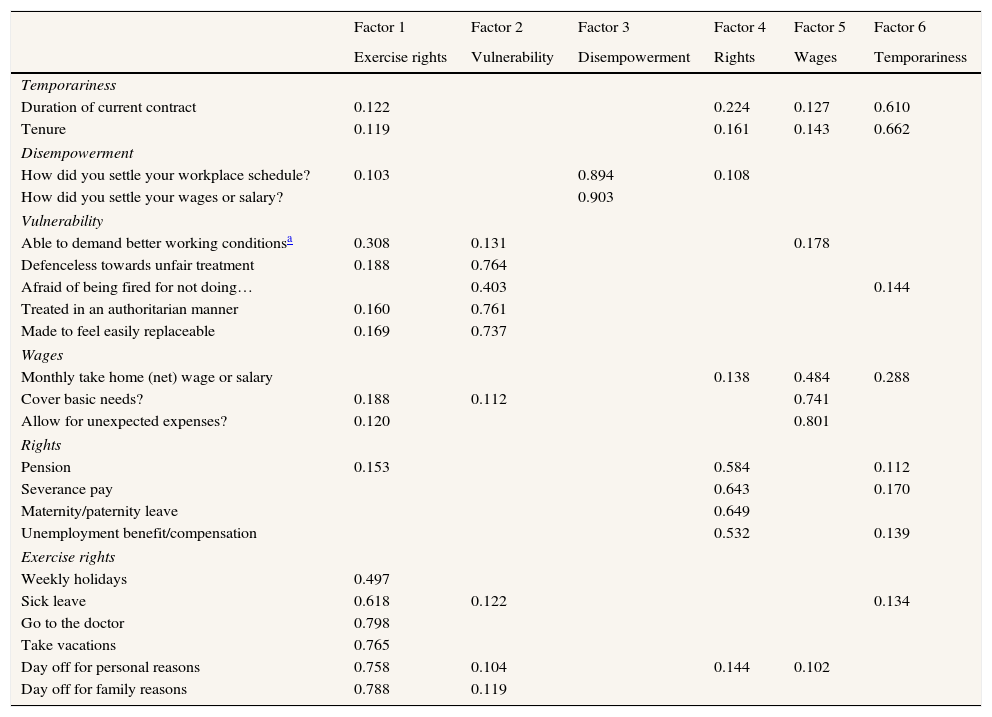

Table 2 shows all items presented the highest loading within their theoretical subscale; loadings were all above 0.35. The only exception was item 1 in ‘vulnerability’, which loaded highest in ‘exercise rights’ (0.31). The rotated factor model explained 51% of cumulative variance (and 53% if item 1 in vulnerability is removed).

Exploratory factor analysis of the Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES-2010). Salaried workers, PWES survey, Spain, 2010.

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 | Factor 5 | Factor 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise rights | Vulnerability | Disempowerment | Rights | Wages | Temporariness | |

| Temporariness | ||||||

| Duration of current contract | 0.122 | 0.224 | 0.127 | 0.610 | ||

| Tenure | 0.119 | 0.161 | 0.143 | 0.662 | ||

| Disempowerment | ||||||

| How did you settle your workplace schedule? | 0.103 | 0.894 | 0.108 | |||

| How did you settle your wages or salary? | 0.903 | |||||

| Vulnerability | ||||||

| Able to demand better working conditionsa | 0.308 | 0.131 | 0.178 | |||

| Defenceless towards unfair treatment | 0.188 | 0.764 | ||||

| Afraid of being fired for not doing… | 0.403 | 0.144 | ||||

| Treated in an authoritarian manner | 0.160 | 0.761 | ||||

| Made to feel easily replaceable | 0.169 | 0.737 | ||||

| Wages | ||||||

| Monthly take home (net) wage or salary | 0.138 | 0.484 | 0.288 | |||

| Cover basic needs? | 0.188 | 0.112 | 0.741 | |||

| Allow for unexpected expenses? | 0.120 | 0.801 | ||||

| Rights | ||||||

| Pension | 0.153 | 0.584 | 0.112 | |||

| Severance pay | 0.643 | 0.170 | ||||

| Maternity/paternity leave | 0.649 | |||||

| Unemployment benefit/compensation | 0.532 | 0.139 | ||||

| Exercise rights | ||||||

| Weekly holidays | 0.497 | |||||

| Sick leave | 0.618 | 0.122 | 0.134 | |||

| Go to the doctor | 0.798 | |||||

| Take vacations | 0.765 | |||||

| Day off for personal reasons | 0.758 | 0.104 | 0.144 | 0.102 | ||

| Day off for family reasons | 0.788 | 0.119 | ||||

Loadings <0.1 are not presented.

Correlations between EPRES-2010 subscales were all lower than their reliability coefficients, indicating unique reliable variance is being measured by each subscale.7 All inter-scale correlations were positive and low (≈0.3); correlations between the global score and each subscale were substantial (0.47-0.64). Although not a central objective of the study, we additionally performed all psychometric analyses for women (n=2,079) and men (n=2,671) separately, obtaining highly similar results.

DiscussionThe revised Employment Precariousness Scale (EPRES-2010) demonstrated good psychometric properties (acceptability, score distributions, reliability and structure) overall and for both women and men, with improvements in those aspects that were modified following previous recommendations.3

Regarding subscales subject to significant changes, we observed several expected improvements: a notable reduction of floor effects (and increased mean) in ‘temporariness’ among permanent workers, and a notable reduction of overall floor effects in ‘vulnerability’. The latter is possibly due both to the rewording of items and to changes in the socioeconomic context that increase workers’ labour market insecurity and vulnerability. In fact, unmodified ‘vulnerability’ items also exhibited increased means in 2010 (data not shown). Consistent with this, lower floor effects were also observed in ‘exercise rights’, which underwent minor changes, although the magnitude of this change was comparatively small.

In contrast, floor effects increased for ‘disempowerment’ for temporary and permanent workers. While this could be due to the broader range of response categories, we observed similar changes in both direction and magnitude for ‘rights’, which underwent no significant changes. Jointly, these increased floor effects suggest higher worker awareness regarding their terms of employment in 2010. In fact, the endorsement of ‘I don’t know’ responses fell on all comparable items in both subscales. This may be partly due to the greater proportion of long-tenured workers in this sample, who are better informed of their employment conditions.

Factor analysis showed that the reworded item ‘ability to demand better working conditions’, did not load into its corresponding subscale (vulnerability), possibly due to the positive wording now used, closer to that of ‘exercise rights’ items. In future applications of EPRES this item should be reworded in order to fit its corresponding subscale.

The study is not without limitations. Differences between this and the 2004-05 study3 must be interpreted with caution given important sample differences. The 2010 sample includes a smaller proportion of women, young workers, temporary workers, and short tenured workers (most precarious), and a larger proportion of workers aged 50 or more, with secondary education, and with permanent contracts (least precarious). Being a sample with less labour market disadvantage may explain the higher floor effects of ‘disempowerment’ and ‘rights’, whereas the reduction in floor effects in ‘temporariness’ and ‘vulnerability’ are most likely due to improvements in the questionnaire and the deterioration of the labour market situation.

The EPRES-2010 preserved the scale's good metric properties while improving its ability to capture employment instability among permanent workers and its capacity to measure ‘vulnerability’. Results also indicate that EPRES-2010 is appropriate for use in high-unemployment contexts. Furthermore, the multidimensionality of the scale appears most suitable in these circumstances, demonstrating increases in the employment precariousness of workers in some dimensions (vulnerability, exercise rights), despite falls in other more contractual dimensions (disempowerment, wages, rights) which reflect the disproportionate out-selection, from the labour market, of workers with temporary jobs.

The Employment Precariousness Scale was first validated with 2004-05 Spanish data. Suggestions were then made to improve some aspects of the scale. A revised version of EPRES was used in 2010, requiring evaluation both of the changes performed and of its functioning in a high unemployment context.

What does this study add to the literature?The revised EPRES demonstrated improved psychometrics and the capacity to capture how high unemployment is affecting the degree of employment precariousness of workers still in the workforce. In addition to providing with a useful instrument for occupational health research, this study illustrates the importance of a multidimensional approach for the assessment of employment conditions for both monitoring and research in changing socioeconomic contexts.

This study was partially supported by CONICYT/FONDECYT Iniciación 11121429, by Pontificia Universidad Católica VRI/DID/104/2011, the European Community‘s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under grant agreement n° 278173 (SOPHIE project), Programa Estatal de Fomento de la Investigación Científica y Técnica de Excelencia del Ministerio de Economía y competitividad n° CS02013-45528-P (CriSol), and Fundación para la Prevención de Riesgos Laborales and the Generalitat de Catalunya.

Authorship contributionsA. Vives and F. González designed the analysis. A. Vives drafted the manuscript. F. González performed the analysis. A. Vives, J. Benach, C. Llorens and S. Moncada worked in the adaptation of the questionnaire. S. Moncada and C. Llorens provided all the data for this study. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results, critically revised the work and approved the final version to be published.

Editor in chargeCarlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would particularly like to thank Marcelo Amable for his advice in the adaptation of the questionnaire.