Gender-based violence against women migrant domestic workers (WMDW) is a serious public health concern in the Middle East region. The current study is the first to explore abuse of WMDW as perceived by recruitment agency managers.

MethodA qualitative study was conducted using 42 personal semi-structural interviews with agency managers in Lebanon. The interview guidelines were designed based on the standards set by the International Labor Organization (ILO) Convention No. 189. The information was transcribed in Arabic, and data was analyzed using thematic analysis.

ResultsThe interviewees believe that WMDW are subject to abusive practices that represent various violations of the ILO Convention No. 189, including harassment and violence, compulsory labour, misinformation about conditions of employment, denial of periods of rest and restriction of movement and travel documents. In many situations, the interviewees justified some of these practices as being necessary to protect their business and to protect the workers.

ConclusionThe results of this study have several policy implications for the protection of WMDW against abuse.

La violencia basada en el género contra las trabajadoras domésticas inmigrantes es un problema serio de salud pública en Medio Oriente. El presente estudio es el primero que explora el abuso de trabajadoras domésticas inmigrantes tal como lo perciben los/las gerentes de empresas de contratación de trabajo doméstico.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio cualitativo basado en 42 entrevistas personales semiestructuradas con gerentes de agencias en Líbano. El guion de la entrevista se basó en los estándares establecidos por el Convenio N.° 189 de la Organización Internacional del Trabajo (OIT). La información se transcribió en árabe y los datos se analizaron utilizando un análisis temático.

ResultadosLas personas participantes creen que las trabajadoras domésticas inmigrantes están sujetas a prácticas abusivas que representan diversas violaciones del Convenio N.° 189 de la OIT, incluidos el acoso y la violencia, el trabajo forzado, la desinformación sobre las condiciones de trabajo, la negación de periodos de descanso, el encierro y el confinamiento del pasaporte. En muchas situaciones se justifican algunas de estas prácticas como necesarias para proteger sus negocios y proteger a las trabajadoras.

DiscusiónLos resultados de este estudio tienen varias implicaciones de política para la protección de las trabajadoras domésticas inmigrantes contra el abuso.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) issued the convention No. 189 in 2011 to set standards for the treatment of women migrant domestic workers (WMDW), and to prevent labor exploitation.1 The convention is made of 27 articles, which include: eliminating all forms of compulsory labor (Article 3), giving WMDW the right to keep their travel documents, giving the freedom of residency and the liberty to leave the household during periods of rest (Article 9), and giving the right to take 24 consecutive hours of weekly rest (Article 10). However, many Arab countries, including Lebanon have not yet ratified this convention. WMDW in Lebanon are still excluded from most laws and policies covering national workers. In general, the legal and policy framework in Lebanon does not provide protection of human and labor rights of WMDW and make them vulnerable to exploitation and abuse.

Lebanon is a middle-income country and one of the top nations relying on WMDW with over 250,000 WMDW working in private households.2 The largest proportion of WMDW comes from Bangladesh, the Philippines, and Ethiopia, with the great majority being recruited through recruitment agencies.3 There is no set minimum wage for WMDW in Lebanon, with salaries ranging from $150-300/month depending on nationality, experience and language proficiency. The recruitment of Bangladeshi (recently also Ethiopian) workers has the lowest cost, as the travel costs are often deducted from their salaries. The recruitment of Filipina workers has the highest cost, as they are smuggled through Gulf countries after the ban that the Philippines had established against domestic work in Lebanon.3 The recruitment process of WMDW through agencies costs employers between $2000-3000, including the costs of travel, visa, residency, work permit, notary fees and health insurance.

The subject became of particular relevance in this region with the emergence of recurrent reports on human right violations and abuse of WMDW.2 A recent study described injuries and psychological trauma among Sri-Lankan WMDW returning home from the Middle East, and documented widespread complaints concerning confiscation of travel documents and restriction of movement.4 Another study described exploitative treatment, forced confinement of movement, and undermining of cultural identity among Ethiopian WMDW, which resulted in adverse outcomes on their psychological wellbeing.5

With the estimated 250,000 WMDW working in private households, exploitation, abuse and discrimination of WMDW are well documented in Lebanon.6,7 An assessment of psychiatric morbidity among WMDW detected frequent sexual, physical, and verbal abuses against workers, who were regularly diagnosed with a wide spectrum of psychotic disorders, including psychotic episodes, acute anorexia, nudity, catatonic features and delusion of pregnancy8. In 2008, the Human Rights Watch documented an average of one death per week of WMDW, mainly due to suicide and falls from buildings.9 More recently, a Human Rights Watch report of The Guardian in 2014 documented that most of the common complaints registered by civil society organizations and embassies of countries of WMDW include non-payment or delayed payment of wages, forced confinement, refusal to provide time off, forced labor and physical and verbal abuse10. The Lebanese non-governmental organization KAFA also documented a widespread of forced long working hours (˃14h/day) and reported various cases of sexual abuse by employers.11 The Lebanese justice system has never punished employers who confined movement of WMDW or withheld the employees travel documents, and the worst sentence for physical abuse is one month in prison.12

Migrant labor in Lebanon is regulated under the General Security's Kafala13 or sponsorship system. In this system, recruitment agencies are held responsible for the workers and act as mediators between workers and employers. Kafala, being a set of customary practices that has been taken for granted and not really a law per se, deprives WMDW from basic protection through national labor laws. Kafala also ties residence and work permits of WMDW to one specific employer, thus limiting their capacity to refuse working under exploitative or abusive working conditions.

The sponsor (kafeel) covers travel costs, medical insurance and residence permits, and is legally responsible for the worker. In this context, the labor law does not contain adequate provisions to guarantee the basic human rights of WMDW, but practically generates, facilitates and foments abuse. Actually, the Kafala system itself contradicts the ILO convention No.189, and makes workers increasingly vulnerable to abuse14. Firstly, the kafeel is able to cancel WMDW's residency and deport them without prior notice, violating the ILO convention No.189, Article 3. Secondly, the kafeel is entitled to change employment conditions, leaving the worker with no choice but to surrender to unfair terms of employment, lower wages and deficient living conditions, which violate Article 7. In addition, workers sign a compulsory standard employment contract available only in Arabic language, representing another violation of Article 7 that states: “Domestic workers must be informed of their terms and conditions of employment in an easily understandable manner, preferably through a written contract”. The objective of this study is to explore the perceptions of recruitment agencies managers towards abuse of WMDW in Lebanon and to explore the violations of the 189-ILO convention.

MethodDesign and study populationA qualitative descriptive study was conducted through personal semi-structural interviews with managers of agencies that recruit WMDW. The study population included 42 agency managers in Lebanon. After obtaining the official list of registered recruitment agencies from the Ministry of Labor, agencies were selected from the five main provinces in Lebanon using a stratified random sampling technique. From the 497 agencies, 22 agencies were selected from Beirut, 7 agencies from each of the North and South governorates, and 6 agencies from Bekaa. From the 42 selected agencies, 8 agency managers refused to be interviewed; they were replaced by alternative agencies from the same province. The selection of the replacement agencies took into consideration the criteria of feasibility and convenient access to participants.

Data collectionThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the researchers’ university. Data was collected by the three authors who were public health researchers trained on qualitative techniques. Data collectors did not have any relationship with any of the interviewees. Researchers approached the managers face-to-face at their agencies and briefed them about the study objectives. Verbal informed consent was obtained before starting the interviews and participants were guaranteed that the data would be kept anonymous and confidential. Verbal consents were given, as the interviewees were not familiar with the research modality and many were reluctant to sign a written consent form.

All interviews were audio-recorded using a digital recorder, except for three interviews, where managers refused to be recorded. In these interviews, data was taken in written form. Interviews were conducted in Arabic language, lasted around 40minutes, and were held at the agencies. The interview guideline (available as supplementary material) was inspired by the standards set by the ILO Convention No. 189. Only standards that were applicable under the Lebanese Kafala system were adopted. The guideline included questions related to three main areas: employment contract terms, protection of WMDW from abuse, and conditions of deportation after employment. Examples of questions include: “Describe the most common practices of WMDW that hurt recruitment agencies”; “Which of these practices violate the contract terms?”; “Discuss the most common registered complaints of WMDW about abuse?”. Field notes were taken after concluding the interviews.

The required number of interviews (42 interviews) was determined after reaching data saturation,15 when no new information was likely to be obtained to answer the study objectives, and sufficient information was collected to replicate the findings.16

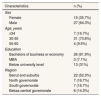

27 males and 15 females participated in the study. Participants aged between 35-50 years old and had more than 5 years of experience in agency work. Characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Socio-demographic and work-related characteristics of participants.

| Characteristics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 15 (35.7%) |

| Male | 27 (64.3%) |

| Age, years | |

| ≤34 | 7 (16.7%) |

| 35-50 | 31 (73.8%) |

| 50-60 | 4 (9.5%) |

| Education | |

| Bachelors of business or economy | 26 (61.9%) |

| MBA | 3 (7.1%) |

| Below university level | 13 (31%) |

| Region | |

| Beirut and suburbs | 22 (52.3%) |

| North governorate | 7 (16.7%) |

| South governorate | 7 (16.7%) |

| Bekaa central governorate | 6 (14.3%) |

In the analysis, authors aimed to identify emergent themes that arise from the content of the interviews to any topic related to the abuse, discrimination, and maltreatment of WMDW, as reflected by the recruitment agency managers. Thematic analysis was applied to data as authors tried to understand the information gathered from the interviews and to analyze their content in order to provide an understanding of the phenomenon of abuse against WMDW from the perspective of recruitment agency managers. As the research also aimed at exploring violations of the ILO 189 Convention, some of the codes were pre-established a priori under deductive labels corresponding to some of the articles of the 189-ILO convention articles.

Sentences with the same meaning were identified, which were coded and grouped by the first two authors to form categories. Representative quotes were chosen to support the interpretation of findings. Core information was obtained about the reasons, patterns and justification of abusive practices against WMDW were described after coding and categorizing data and assembling the themes. After data collection, interviews were transcribed in English and entered into Atlas Ti5 software for facilitating the analysis.

ResultsThree main themes were derived from the data, which explain the phenomenon of abuse against WMDW and the violations of the 189-ILO convention. The first theme summarized how agency managers perceive WMDW according to their nationality, and highlighted some of their behaviors that were considered by the managers as unacceptably harmful. The second theme highlighted the reasons that drive WMDW to adopt these negative behaviors based on the opinions of agency managers. The third theme described the types of abuse practiced against WMDW, and how agency managers sometimes justified this abuse. Under this theme, categories and subthemes explained violations of the 189-ILO convention.

WMDW as perceived by agency managerParticipants complained about several practices of WMDW that cause harm to the agency and the employers. The most highlighted practices were: running away, refusing to work, demanding to go back home, demanding periods of free time, demanding to go out on their own during free time and having psychological disturbances that could lead to violence. Participants shared several negative attitudes towards WMDW and stereotypic behaviors according to their nationality. Participants believed that Bengali workers are “famous for escaping and entering the freelance business”. They reported that some Bengali workers “create gangs that practice theft and prostitution”. Filipina workers were generally considered “educated, strong and demanding. Absolutely all of Filipina workers require going out on Sunday on their own. Workers of other nationalities are rarely allowed… well it depends on the employer too”. Filipina workers also “escape with boyfriends and occasionally get married to Lebanese citizens”. It was frequently mentioned that Ethiopian workers “could be dangerous, get mad and get haunted by devil”. Many times, they “refuse to work and demand to travel back home”. Sometimes, they “threaten the host family members by killing themselves or swallowing huge amounts of pills”. They are also considered “fast learners and smart” but have a “problematic character and frequent psychological disturbances”. Superstitions around Ethiopian workers who “practice black magic” were frequently encountered in participants’ discourses. One agency manager described a situation when he witnessed an Ethiopian worker “haunted by the demon”: “Her eyes were still as glass, she started to pull her hair and to hit her head against the wall”. Workers from Sri Lanka were mostly described as being “peaceful, loyal and committed to work”, although, some interviewees complained about their frequent escape.

Why do WMDW abuse agencies?Agency managers explained why WMDW would run away, refuse to work and become aggressive and psychologically disturbed. One participant proclaimed: “when they are mistreated or denied a day off to visit the church on Sunday, they feel demotivated and refuse to work”. Another reason is that workers become frustrated when they realize that they are taken advantage of by employers that define labor duties not mentioned explicitly in the contract. These duties include “working in weekends and taking care of the elderly”. Many times, workers “accept the contract, with its misleading terms, as an opportunistic transit act and remain unaware about its particularities” added another. For instance, “upon arrival, many workers are unaware that they are expected to remain on standby 24/7”. One participant further explained that another reason that provokes these WMDW's practices is the issue of withholding wages: “Some employers withhold wages until the end of the year and often threaten the worker not to pay, causing anxiety and instability in the relationship”. This issue could cause psychological distress and disturbances and could lead WMDW to refuse to work further, try to escape.

Abuse against WMDW through violations of the 189-ILO conventionThe analysis of the content of the discourses revealed that there are several abusive and discriminating acts practiced by employers, by agencies working in the black market, and by agency managers themselves against WMDW. Agency managers condemned some forms, but also justified other forms of abuse practiced by employers against WMDW. It appeared that many managers discriminate, and in certain ways themselves, abuse WMDW and encourage their clients to take protective measures that most of the times violates the 189-ILO convention. The protection of the agency business was the managers’ main priority, and workers’ rights came next. One participant (I12, Beirut) illustrated this viewpoint: “Each worker costs me around $2000. They sign a contract; why did they come since the beginning, why do they suddenly decide that they no longer want to work? Isn’t it a commitment? I mean, I won’t allow that I lose my investment for a worker's caprice. It is necessary to be firm, to control and to prevent them from abusing us”.

In the following paragraphs we summarize the abusive practices described by agency managers during the interviews, describing certain situations where agency managers disapproved abuse and others where they justified it. Abuse was classified according to the violations of articles of 189-ILO convention.

Compulsory labor and discrimination (Article 3, Convention 189-ILO)Agency managers pronounced several manifestations that discriminate WMDW by race and by work class:

- •

“Since they are not Lebanese, they cannot be rewarded in an equal way as Lebanese”– I3, Beirut.

- •

“They would never dream about gaining such money in their home country”– I9, Beirut.

- •

“You cannot treat them like doctors”– I25, North governorate.

- •

“If you hire a servant, she should expect what is waiting for her”– I17, Beirut.

On the other hand, participants described situations where WMDW become victims of compulsory labor. One stated: “many employers treat their workers as machines and make them work at three different houses all week long without extra payment”. Participants clarified that the issue of payment for such extra labor is usually left to the courtesy of the employers. While all managers considered compulsory labor as economic abuse, one explained that sometimes it is difficult to differentiate between compulsory labor, labor due to bulling or labor with the WMDW's consent: “They are expected to work only in one house as per the contract. Now when they are offered extra money to clean houses of relatives, usually they accept with pleasure, and what is the problem if they like to gain extra money? Although sometimes, they are not paid enough to work in extra houses and this is abuse. Sometimes employers falsely believe that they are fair, but the worker is just intimidated or bullied and do not dare to complain”– I30, South governorate.

Abuse, harassment and violence (Article 5, Convention 189-ILO)Many participants witnessed situations in which host family members physically abused WMDW. They also frequently receive calls from their partner recruitment agencies at the workers’ home country with complaints about physical abuse. Other interviewees described situations when workers were brought to their offices by host family members with “visible signs of heavy beatings with shoes or sticks, or slaps on the face”. Participants assured that physical abuse is widely practiced by agencies in the black market. Most participants clearly condemned physical abuse and considered that violence is never justifiable regardless of the situation:

- •

“Whenever I hear physical abuse allegations, I immediately break the contract with the employer”– I38, Bekaa;

- •

“Many employers threaten workers and use force in ways that don’t leave visible signs, like frequently pulling the worker's hair, inflicting severe pain”. She angrily described some agencies as “resembling torture houses for workers who misbehave”– I2, Beirut.

Few participants justified physical and verbal violence against the worker. They even recommended their clients to be strict and to threaten workers with beating if they refuse to work:

- •

“We have to be harsh sometimes with those who must know that they cannot simply refuse to work or fail to do her duties as per the contract terms”– I1, Beirut

- •

“When the client complains that the worker does not obey orders, I tell them to bring her to the office…usually after being shown the red eye (colloquial Arabic term that means the hard way, like after being yelled), they go back to work as sharp as a clock”– I36, South governorate.

Three participants (all males) acknowledged that they approve using force when necessary in order to exert control: “Sometimes, there is no other solution but to use force. You know they could be dangerous and aggressive and should be controlled somehow”– I1, Beirut.

All participants clearly condemned rape and sexual harassment. However, it is important to mention that two agency managers indirectly rationalized sexual abuse, saying “sometimes the worker is happy when her employer approaches her and it becomes her problem when she does not want to resist”.

Understanding the terms and conditions of employment (Article 7, Convention 189-ILO)Throughout the interviews, it became clear that worker's duties are not mentioned explicitly in the contract and are instead defined by the employer. These duties include “working in the weekends and at night” and “having to take care of elderlies in the house”. Another explained that “in some agencies, especially those of the black market, workers are usually left with misleading contract terms and are commonly taken advantage of… they sign a contract in Arabic and most of the times they have no idea about its content. Agencies usually do not translate the contract into Ethiopian or Bengali”.

Periods of rest and standby hours (Article 10, Convention 189-ILO)The analysis of the content of the interviews revealed that both employers and agency managers generally take for granted that WMDW remain pending all the time to attend to all of the employers’ demands. One participant (I4, Beirut) explained his point of view: “It is a question of mutual understanding; first that the worker understands that being a helper, she should do her best to help whenever needed, when guests come at night or whenever there is much workload in the house. Second, that the demanding employer understands that overloading the worker with tasks in any unexpected moment would put her under pressure and psychological distress.”

The language of asking appeared to matter in this regards: “When the worker feels discriminated, she becomes nervous and unhappy. She certainly differentiates between being addressed by orders and by compassion”.

Several quotes illustrated how participants justified long working and standby hours:

- •

“The worker is a normal resident of the house. She does not have a fixed work schedule as office workers do. She is expected to assist family members whenever needed”– I10, Beirut;

- •

“They know from the beginning that they should remain on standby for 24hours without being paid extra money, why are you so concerned about their rights?”– I1, Beirut;

- •

“Fine, it is not heavy work always, but for example, they are expected to help simply anytime when needed to help preparing breakfast, lunch and dinner. I mean she is here for that, even if at night”– I41, Bekaa.

However, one manager clarified his point of view: “It can sometimes be too much to handle when the WMDW has to be on hold and has to quickly respond to any little request from her employer, ranging from bringing the remote control to the sofa while she is lying, or cleaning her employer's shoes quickly before he leaves the house. There is a thin line of abusing the worker with demands and expecting help.”– I32, South governorate.

Obligation to remain in household during rest, and possession of travel documents (Article 9, Convention 189-ILO)It appeared that employers, also advised by agencies, usually “forbidden them to leave without permission, rarely give them the apartment keys, and many times lock them in the apartments when they go out”. In fact, agency managers considered that WMDW should not be allowed to leave the house during free time “unless employers gain confidence that they will not escape”.

All participants considered that retaining travel documents at the agency or with employers is a normal and necessary practice to prevent them from escaping: “It is a standard practice, a guarantee to protect the investment of the agency and employer”. Even the general security officers advise employers and their family members to withhold the worker's passport to prevent possible escape”– I3, Beirut

Most managers considered that confining WMDW's movement is always justified, as WMDW are under the custody of their employers during their stay in Lebanon. The following quotes highlight this perspective:

- •

“It's for her own safety”-I1, Beirut;

- •

“They are not familiar with the places in Lebanon. If they want to go to churches, the hosting family members would better accompany her to avoid any contact with people that might harm or convince her of escaping, stealing or prostitution”– I30, North governorate;

- •

“It protects them from being involved in relationships, getting pregnant and catching disease”– I9, Beirut;

- •

“There are gangs everywhere, and they are well covered from the police, they seduce the worker to leave her house and work for them, without telling her that it is prostitution”– I7, Beirut;

- •

“You cannot trust them to go out alone, what happens if they escape?”– I42, Bekaa.

One of the participants (I21, Beirut) defined the financial obligations of the employers towards WMDW: “All logistic fees in Lebanon should be borne by the employer including airfare, three-month working visa, residency and work permits, notary fees and medical insurance”.

Some participants condemned agencies that do not pay WMDW for their services during their first two or three months: “Many agencies agree with workers upon signing the contract that the remuneration of the first few months will pay back the flight ticket. This way they are able to offer cheaper services for clients”– I25, North governorate.

Others did not perceive any abuse in deducting salaries from the remuneration of WMDW to pay her ticket back. One proclaimed: “If they accept the contract as such, then there is no harm in this. You have to understand that they consider lucky those who have the chance to come here”– I6, Beirut.

On the other hand, participants described how many employers withhold wages in order to prevent WMDW from escaping before the end of the contract duration. Most managers disapproved this practice.

DiscussionEmployment agency managers described how employers practice abuse and exploitation of WMDW in violation to various articles of the ILO Convention No. 189. In some instances, they justified some of these practices. Driven by fear that workers would escape and concerns for the protection of the agency's financial investment in the recruitment process, employers and agency managers exercise strict control over WMDW's movement and withhold their travel documents. This results in a lack of trust in the relationship between the WMDW and their employers,17 which in turn might cause WMDW to do harmful practices, in accordance with Ortner's transformative potential caused by fundamental instability.18

Participants justified these practices using industry-driven notions such as “risk minimization” and “cost-benefit” and did not hide that their main concern is “fair profit”. Most of the times, agency managers appeared more concerned to protect their profit, and in return treated workers as trade items, giving the human aspect less priority.

The conception of stereotypes about WMDW according to their nationality shaped employers and family members’ practices towards workers in attempt to dealing with them adequately. Agency managers believed that vulnerability of WMDW is attributed to the absence of protective legislations and to limited opportunities of WMDW to take control over their basic rights.

Although Lebanon reviewed the provisions and voted on the ILO Convention No.189, it still has to take active steps to ratify the convention. In this context, the Lebanese justice system does not defend the rights of WMDW. For instance, judges address WMDW in either English or French without offering them a translator to their mother language, opposing the Standard Unified Contract.19

Abuse practiced against WMDW and violations of the ILO Convention No.189 have been previously observed in Lebanon and in other settings.6,20–22 Previous reports showed that almost all employers in Lebanon withhold the travel documents, the majority do not provide WMDW with a copy of their contract and 20% of them lock WMDW inside the house.6 Other studies have described the vulnerability and social and health inequalities among WMDW23 and associated physical, psychological and economic abuse of WMDW with various adverse health events.24 Other studies described psychopathologies among Filipina and Indonesian WMDW in the Hong Kong25 and showed that WMDW in Sri Lanka, especially in young age groups, have more risk of death relative to their counterparts.26

Study limitationsThe current research has several limitations that should be taken into consideration upon interpreting the findings. First, although most interviews were recorded, information from the three interviewers who refused to take records was taken in written form, which might have introduced some information bias to the results. In addition, data was gathered from officially registered agencies. It would be interesting to collect data from agencies that work in the black market, especially when interviewers indicated that they quite frequently practice abuse against WMDW. To reduce possible bias and misinterpretation of the collected information, data was jointly coded and categorized by two researchers. Furthermore, findings were discussed with the research team including sociologists in order to improve data accuracy. However, another qualitative study should be conducted with WMDW to ensure the validity of the findings.

Policy implicationsPrevious studies on this topic were based on the opinion of the domestic workers and the employers,27,28 knowing that recruitment agencies are key stakeholders in this context. This study, being the first to explore this issue from the perspective of recruitment agencies have important policy implications. International organizations and civil society organizations should continue their advocacy efforts for taking into consideration WMDW in the Lebanese labor law and modifying the Kafala system to the relevant international standards that protect WMDW. For instance, the government should also take active steps for the ratification of ILO Convention No.189. Agencies should also be held responsible for safeguarding the provision of basic human and labor rights of WMDW. They should inform workers about their rights and responsibilities through providing them with copies of the contract and should actively monitor abusive employers. Agency managers should be trained on how to educate and encourage employers to respect the rights of WMDW. Lastly, agencies and employers should understand that practices such as the use of violence, locking workers at home, and the prohibition of workers from 24-hours consecutive rest are unacceptable violation to their terms of the contract. Furthermore, as agency managers recommended, authorities should regulate the industry of WMDW through fighting trafficking and illegal freelance work in the black market. Moreover, it is important for policy makers to set regulations aimed at reducing the inequities among WMDW that inevitably compromise every aspect of their lives.29 Lastly, it is important that agencies and civil society organizations should increase their efforts to provide psychosocial support for WMDW exposed to abuse in order to improve their social coping strategies.

Abuse against women migrant domestic workers is a serious public health concern in the Middle East. In Lebanon, several forms of abuse have been documented including non-payment of wages, forced long working hours, forced confinement, refusal to provide time off, confinement of travel documents and physical, verbal and sexual abuse. Previous studies described abuse as perceived by workers or by employers. This study is the first that explores abuse of women migrant domestic workers as perceived by recruitment agency managers.

What does this study add to the literature?In this study, agency managers described how employers abuse women migrant domestic workers in violation to the ILO Convention No. 189. Agency managers justified some of the abusive practices against women migrant domestic workers in order to protect their financial part of the investment in the recruitment process. Findings call policy makers in Lebanon to take active steps towards ratifying the International Labor Organization Convention 189 for the protection of workers from abuse.

Mercedes Carrasco Portiño.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsA. Ghaddar developed the study design, coordinated data collection, drafted the manuscript, and approved the final version of the article. S. Khandaqji performed the literature review, transcribed the audio-records of the interviews, and drafted the manuscript. J. Ghattas performed data collection.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to acknowledge the NGO: CRTDA, Lebanon for supporting this research.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.