Assess the risk associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women on maternal and neonatal outcomes in Catalonia (Spain) in 2020, before the beginning of COVID-19 vaccination campaign.

MethodCross-sectional descriptive study with all pregnant women (41,560) and their live newborns (42,097) (1st March to 31st December 2020). Women were classified: positive and negative COVID-19 diagnosis during pregnancy. The outcomes analysed were complications during pregnancy, gestational age, admission of newborns to neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and birth weight. Associations among positive COVID-19 and maternal and infant variables were measured with logistic regression models. Results were expressed as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Models were adjusted for nationality, maternal age, socioeconomic status, type of pregnancy and type of centre where the delivery occurred (public or private management hospital).

ResultsA total of 696 women (1.7%) were diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy. Women with COVID-19 were 4.37 times more likely to have complications during pregnancy (4.37; 3.52-5.40). A total of 713 newborns (1.7%) were from mothers with COVID-19. A positive diagnosis of COVID-19 increased the risk of preterm birth (1.41; 1.03-1.89), admission to NICU (1.40; 1.06-1.82) and low birth weight (1.35; 0.99-1.80) in babies.

ConclusionsPregnant women with COVID-19 had higher risk of developing complications during pregnancy and their newborns were more likely to be admitted to NICU and had prematurity.

Evaluar el riesgo asociado de COVID-19 y los resultados en mujeres embarazadas y sus recién nacidos en Cataluña (España) antes del inicio de la campaña de vacunación.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo transversal de mujeres gestantes (41.560) y sus recién nacidos (42.097) (del 1 de marzo al 31 de diciembre de 2020). Las gestantes fueron clasificadas según diagnóstico COVID-19 positivo o negativo durante el embarazo. Los resultados analizados fueron complicaciones gestacionales, semana gestacional, ingreso del recién nacido en la unidad de cuidados intensivos neonatales (UCIN) y bajo peso al nacer. Las asociaciones entre COVID-19 positivo y variables maternas y perinatales se midieron con regresión logística. Los resultados se expresaron con odds ratio e intervalo de confianza del 95%. Los modelos se ajustaron por nacionalidad, edad materna, nivel socioeconómico, tipo de embarazo y titularidad (pública o privada) del hospital donde se dio a luz.

ResultadosUn total de 696 gestantes (1,7%) fueron diagnosticadas de COVID-19 durante el embarazo. Las gestantes con COVID-19 presentaron 4,37 veces mayor probabilidad de tener complicaciones durante el embarazo (4,37; 3,52-5,40). Hubo 713 recién nacidos (1,7%) de gestantes con COVID-19. El diagnóstico positivo de COVID-19 incrementó el riesgo de prematuridad (1,41; 1,03-1,89), ingreso en UCIN (1,40; 1,06-1,82) y bajo peso al nacer (1,35; 0,99-1,80) de los recién nacidos.

ConclusionesLas gestantes con COVID-19 presentaron mayor riesgo de desarrollar complicaciones durante el embarazo y sus hijos tuvieron mayor probabilidad de ingreso en la UCIN y de prematuridad.

Up to 1 May 2022, the novel SARS-CoV-2 had resulted in 512,690,034 confirmed cases and 6,252,316 deaths worldwide, including 11,953,481 cases and 104,668 deaths in Spain.1,2 Specifically in Catalonia, a North-Eastern region of Spain with a population of 7,780,479 in 2020,3 from the first confirmed case on 25 February 2020 until 1 April 2022, there were 2,410,351 confirmed cases and 18,993 deaths, being one of the most affected region in Spain.2 The COVID-19 pandemic has unfolded in several waves and led to major changes in society, economy and healthcare systems. These changes have had an impact on issues including maternal and perinatal health and affected the health and wellbeing of pregnant women and their babies.4

Pregnant women are considered a vulnerable population group to respiratory virus infections since immunological and physiological changes during pregnancy make them more susceptible to infectious diseases.5–7 This may also affect their babies.6,7 Infections by other respiratory viruses, including the influenza virus or other types of coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV, have been associated with complications during pregnancy.5,8

The most frequent conditions in COVID-19 include an increased risk of preeclampsia, eclampsia, HELLP syndrome (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver Enzymes and Low Platelets), severe infections requiring antibiotics, maternal admission, and maternal death. Their babies have higher rates of neonatal morbidity, perinatal mortality, prematurity and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission.9,10

Catalonia participates in the Euro-Peristat Network in order to monitor indicators of perinatal health in Europe.11 The birth rate in Catalonia has fallen steadily over recent years as a result of the economic slump in 2008 and declined further in 2020 (4.8% fewer births than in 2019).12 This drop is consistent with other European countries.13 Furthermore, comparing before the pandemic, the prevalence of prematurity and low birth weight decreased during 2020. In 2020 vs. 2019, preterm birth (6.2% vs. 6.4%) and low birth weight (6.9% vs. 7.4%) declined slightly, meanwhile pregnant complications increased during 2020 (4%) compared with 2019 (3.5%).12

Matching two databases (Registry of newborns and TAGA COVID-19 registry of confirmed COVID-19 cases), allowed us to develop this work. The findings investigated were before the vaccination campaign against COVID-19 that started on December 27, 2020.

The aim of this study was to assess the risk associated with COVID-19 in pregnant women on maternal and neonatal outcomes in Catalonia in 2020.

MethodWe performed a cross-sectional descriptive study aiming to analyse pregnant women and their live newborns in Catalonia in 2020, with more than 58,000 pregnant women and 50,000 live births.

SourcesTwo sources of information were used. On the one hand, the Registry of Newborns of the Catalan Government of Health. This registry, covering all babies born alive and their mothers, collects all notifications from the epidemiological records of the newborn screening programme. On the other hand, we used the confirmed COVID-19 cases reported to the Epidemiological Surveillance Net of the Catalan Government of Health (TAGA COVID-19) (see Figure I in online Appendix). This registry includes results from tests performed among the Catalan population. We excluded from the analysis mothers (and their babies) who gave birth in January and February, as there were no confirmed COVID-19 cases, yet (17.07% of registers). We matched pregnant women from the registry of newborns from March to December and the cases of TAGA COVID-19 registry from the same period and linked databases using the personal identification number in pregnant women cases. When the personal identification number was not available, cases were removed (see Figure I in online Appendix).

Pregnant women were classified in two groups: pregnant women with confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis, and pregnant women without confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis (a negative COVID-19 diagnosis or no tested).

Variables- 1)

Outcomes

The primary outcomes assessed were complications during pregnancy. Complications during pregnancy were classified in three groups: hypertensive and hematologic disorders (preeclampsia/eclampsia/HELLP syndrome, gestational anemia, metrorrhagia, gestational thrombocytopenia), neonatal conditions (intrauterine growth restriction, threatened preterm labor and premature rupture of membranes) and other disorders (gestational diabetes, bacterial infection, obstetric cholestasis, placenta praevia) (see Table I in online Appendix).

Also, gestational age at birth (term ≥37 weeks or preterm<37 weeks), birth weight (normal weight ≥2,500g or low weight <2,500g) and admission of the baby to NICU. Variables were categorized as binary.

- 2)

Explanatory variables

Variables in the analysis referred to sociodemographic and socioeconomic characteristics of mothers: maternal age, nationality (Spanish or non-Spanish), socioeconomic index (standardized index based on the municipality where women lived, categorized as low (average income per person <90), medium (average income per person ≥90 and <110), and high (average income per person ≥110), and environment (rural/urban, based on the number of inhabitants of the municipality being higher or lower than 10,000).14 In addition, we included maternal health characteristics, such as tobacco use (before and during pregnancy), parity (primiparous or multiparous) and type of pregnancy (single or multiple). Variables referred to newborns: sex and breastfeeding at birth. Twins were also included in the analysis. Moreover, we also considered characteristics of the birth, such as type of centre where the delivery occurred (public or private hospitals), the trimester of pregnancy when women were diagnosed with COVID-19: first, second, third trimester, or at the time of delivery and the wave of the pandemic when the delivery took place (categorized as “first wave”, “second wave”, “third wave” or “in between waves”). During the study period, there were three COVID-19 waves in Catalonia. The first, from March 1st to June 6th 2020, the second, from September 23rd to December 12th 2020, the third started in December 13th and lasted until the end of our study period. The period from 7th June to 22th September 2020 was classified as “in between waves”.15

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis with frequencies for categorical variables, and median and standard deviation for numerical variables. All analyses were stratified for women with and without COVID-19 diagnosis. In addition, we used Chi-square and Fisher test to check for differences among categorical variables, while mean differences for numerical variables between the two groups of women were tested using the non-parametric Wilcoxon-test.

Associations between COVID-19 diagnosis and the different outcomes, expressed as binary outcomes, were assessed using logistic regression models with a log link function and robust standard errors expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). The models for our primary mothers’ outcomes were adjusted for nationality, maternal age, socioeconomic index, type of pregnancy and type of centre where the delivery occurred. Models for our primary newborns’ outcomes were adjusted for nationality, maternal age, socioeconomic index, type of pregnancy and type of centre where the delivery occurred. In the logistic regression models, we selected the independent variables according to their association with the primary outcomes analysed, whereas the independent variables were introduced in the models as factor variables. We performed sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the main model.

All analyses were performed with R software (version 4.0.3).

Ethical considerationsAll data used in the analysis were collected during routine public health surveillance activities, as part of the legislated mandate of the Health Department of Catalonia, the competent authority for the surveillance of communicable diseases, which is officially authorized to receive, treat and temporarily store personal data on cases of infectious disease. Therefore, all study activities were part of the public surveillance and were exempt from institutional board review, and did not require informed consent. All data were fully anonymized.

ResultsDuring the study period, 41,560 pregnant women successfully completed their pregnancies and 42,097 babies were born alive in Catalonia. Of the total number of women, 696 (1.7%) were diagnosed with COVID-19 during pregnancy.

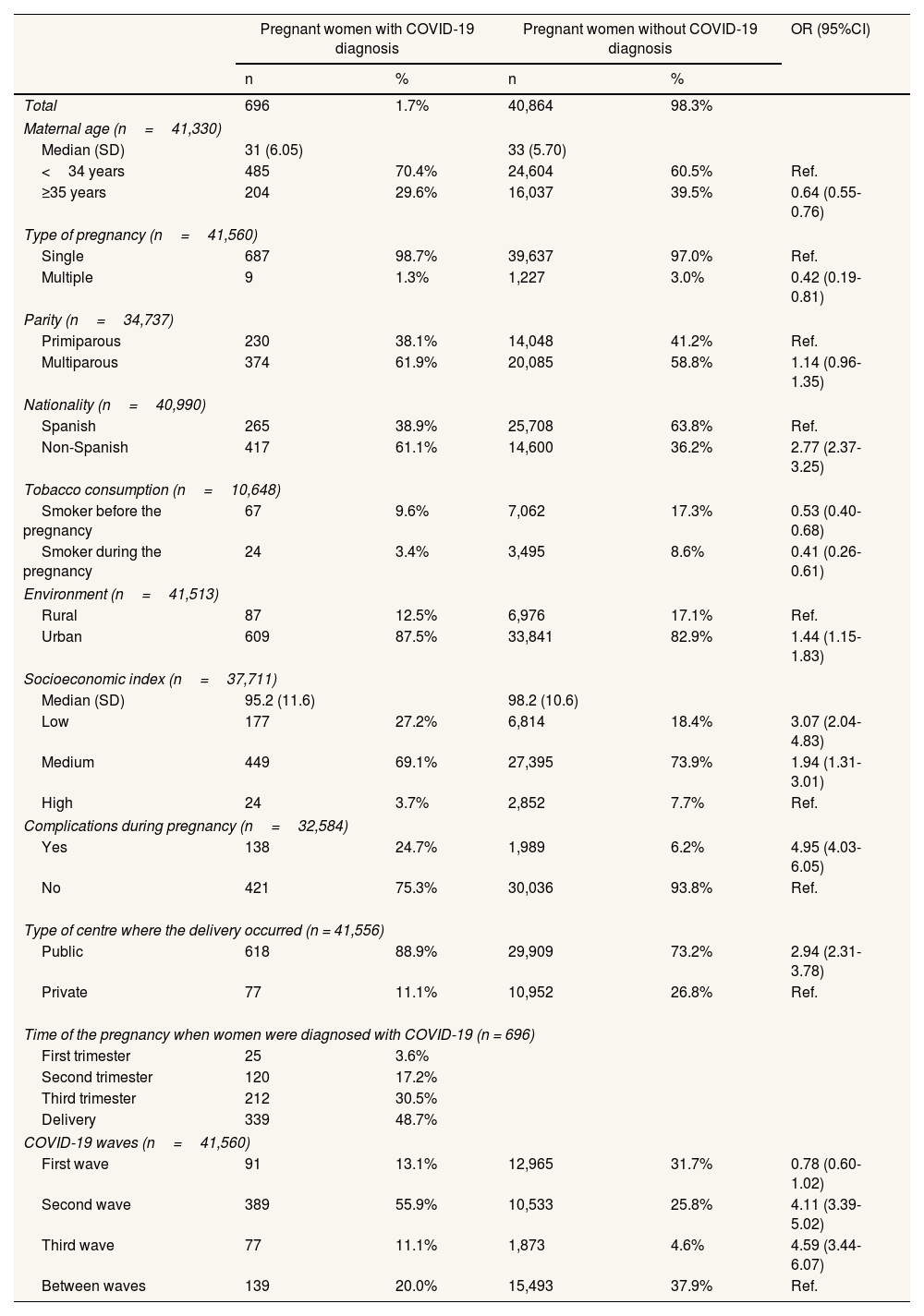

Table 1 shows the characteristics of pregnant women with and without COVID-19. A total of 61.1% of women with COVID-19 were non-Spanish nationality, about 25% more than women without COVID-19 (OR: 2.77; 95%CI: 2.37-3.25). Women with COVID-19 reported less tobacco consumption before (OR: 0.53; 95%CI: 0.40-0.68) and during pregnancy (OR: 0.41; 95%CI: 0.26-0.61) than women without COVID-19. In terms of area of residence, 87.5% of women with COVID-19 lived in urban areas, a higher percentage than women without COVID-19 (82.9%; OR: 1.44; 95%CI: 1.15-1.83). We observed significant differences according to socioeconomic status, having women with COVID-19 lower socioeconomic level (OR: 3.07; 95%CI: 2.04-4.83). In addition, 88.9% of women with COVID-19 gave birth in public hospital while the percentage fell to 73.2% in women without COVID-19 (OR: 2.94; 95%CI: 2.31-3.78). Likewise, women with COVID-19 had more complications during pregnancy (24.7% vs. 6.2%, respectively; OR: 4.95; 95%CI: 4.03, 6.05). There were no statistically significant differences between male and female neonates from COVID-19 women and complication of pregnancy (65 females vs. 73 male; p=0.891). Finally, women with COVID-19 gave birth mainly during the second wave (55.9%) while deliveries among women without COVID-19 occurred mostly between waves period (37.9%) (OR: 4.11; 95%CI: 3.39-5.02). Women were most frequently diagnosed at delivery (48.7%) and in the third trimester of gestation (30.5%). A total of 46% of women with COVID-19 presented symptoms (see Table II in online Appendix).

Characteristics of pregnant women with and without COVID-19 diagnosis.

| Pregnant women with COVID-19 diagnosis | Pregnant women without COVID-19 diagnosis | OR (95%CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 696 | 1.7% | 40,864 | 98.3% | |

| Maternal age (n=41,330) | |||||

| Median (SD) | 31 (6.05) | 33 (5.70) | |||

| <34 years | 485 | 70.4% | 24,604 | 60.5% | Ref. |

| ≥35 years | 204 | 29.6% | 16,037 | 39.5% | 0.64 (0.55-0.76) |

| Type of pregnancy (n=41,560) | |||||

| Single | 687 | 98.7% | 39,637 | 97.0% | Ref. |

| Multiple | 9 | 1.3% | 1,227 | 3.0% | 0.42 (0.19-0.81) |

| Parity (n=34,737) | |||||

| Primiparous | 230 | 38.1% | 14,048 | 41.2% | Ref. |

| Multiparous | 374 | 61.9% | 20,085 | 58.8% | 1.14 (0.96-1.35) |

| Nationality (n=40,990) | |||||

| Spanish | 265 | 38.9% | 25,708 | 63.8% | Ref. |

| Non-Spanish | 417 | 61.1% | 14,600 | 36.2% | 2.77 (2.37-3.25) |

| Tobacco consumption (n=10,648) | |||||

| Smoker before the pregnancy | 67 | 9.6% | 7,062 | 17.3% | 0.53 (0.40-0.68) |

| Smoker during the pregnancy | 24 | 3.4% | 3,495 | 8.6% | 0.41 (0.26-0.61) |

| Environment (n=41,513) | |||||

| Rural | 87 | 12.5% | 6,976 | 17.1% | Ref. |

| Urban | 609 | 87.5% | 33,841 | 82.9% | 1.44 (1.15-1.83) |

| Socioeconomic index (n=37,711) | |||||

| Median (SD) | 95.2 (11.6) | 98.2 (10.6) | |||

| Low | 177 | 27.2% | 6,814 | 18.4% | 3.07 (2.04-4.83) |

| Medium | 449 | 69.1% | 27,395 | 73.9% | 1.94 (1.31-3.01) |

| High | 24 | 3.7% | 2,852 | 7.7% | Ref. |

| Complications during pregnancy (n=32,584) | |||||

| Yes | 138 | 24.7% | 1,989 | 6.2% | 4.95 (4.03-6.05) |

| No | 421 | 75.3% | 30,036 | 93.8% | Ref. |

| Type of centre where the delivery occurred (n = 41,556) | |||||

| Public | 618 | 88.9% | 29,909 | 73.2% | 2.94 (2.31-3.78) |

| Private | 77 | 11.1% | 10,952 | 26.8% | Ref. |

| Time of the pregnancy when women were diagnosed with COVID-19 (n = 696) | |||||

| First trimester | 25 | 3.6% | |||

| Second trimester | 120 | 17.2% | |||

| Third trimester | 212 | 30.5% | |||

| Delivery | 339 | 48.7% | |||

| COVID-19 waves (n=41,560) | |||||

| First wave | 91 | 13.1% | 12,965 | 31.7% | 0.78 (0.60-1.02) |

| Second wave | 389 | 55.9% | 10,533 | 25.8% | 4.11 (3.39-5.02) |

| Third wave | 77 | 11.1% | 1,873 | 4.6% | 4.59 (3.44-6.07) |

| Between waves | 139 | 20.0% | 15,493 | 37.9% | Ref. |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation.

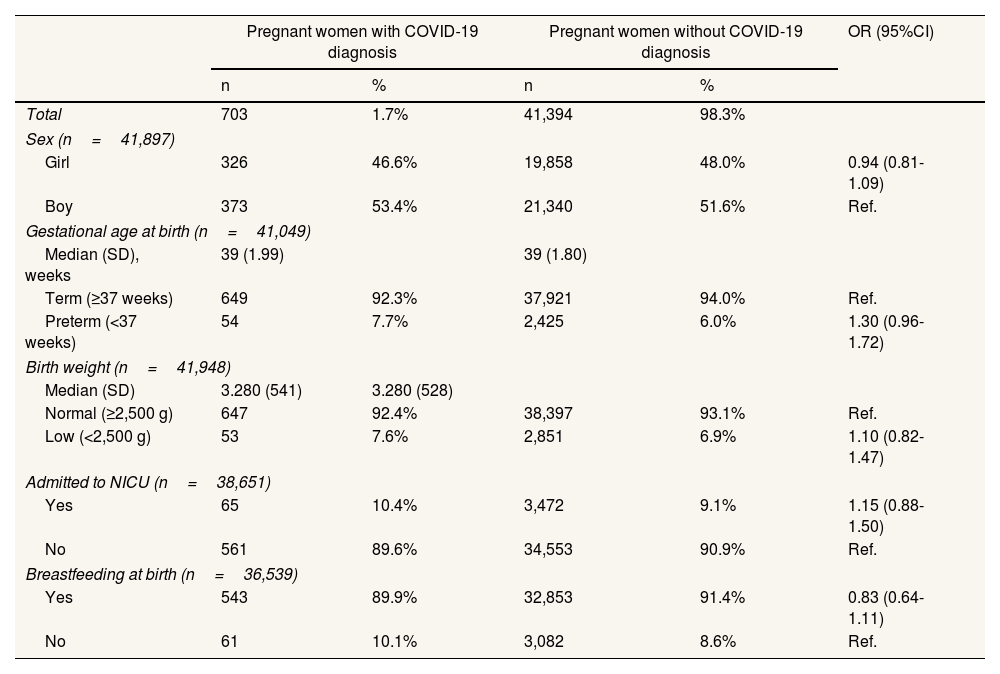

The characteristics of the babies are presented in Table 2. A total of 42,097 babies were born, of which 703 (1.7%) were from mothers with COVID-19. The mean gestational week at birth for both groups of women with and without COVID-19 was 39 weeks, with no significant differences. There were also no significant differences in the other variables analysed. Neonates from mothers with COVID-19 and non- Spanish nationality had a higher prevalence of NICU (10.7%) than neonates from Spanish mothers with COVID-19 (8.6%) (see Table III in online Appendix).

Characteristics of newborns of pregnant women with and without COVID-19 diagnosis.

| Pregnant women with COVID-19 diagnosis | Pregnant women without COVID-19 diagnosis | OR (95%CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Total | 703 | 1.7% | 41,394 | 98.3% | |

| Sex (n=41,897) | |||||

| Girl | 326 | 46.6% | 19,858 | 48.0% | 0.94 (0.81-1.09) |

| Boy | 373 | 53.4% | 21,340 | 51.6% | Ref. |

| Gestational age at birth (n=41,049) | |||||

| Median (SD), weeks | 39 (1.99) | 39 (1.80) | |||

| Term (≥37 weeks) | 649 | 92.3% | 37,921 | 94.0% | Ref. |

| Preterm (<37 weeks) | 54 | 7.7% | 2,425 | 6.0% | 1.30 (0.96-1.72) |

| Birth weight (n=41,948) | |||||

| Median (SD) | 3.280 (541) | 3.280 (528) | |||

| Normal (≥2,500 g) | 647 | 92.4% | 38,397 | 93.1% | Ref. |

| Low (<2,500 g) | 53 | 7.6% | 2,851 | 6.9% | 1.10 (0.82-1.47) |

| Admitted to NICU (n=38,651) | |||||

| Yes | 65 | 10.4% | 3,472 | 9.1% | 1.15 (0.88-1.50) |

| No | 561 | 89.6% | 34,553 | 90.9% | Ref. |

| Breastfeeding at birth (n=36,539) | |||||

| Yes | 543 | 89.9% | 32,853 | 91.4% | 0.83 (0.64-1.11) |

| No | 61 | 10.1% | 3,082 | 8.6% | Ref. |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; NICU: neonatal intensive care unit; OR: odds ratio; SD: standard deviation.

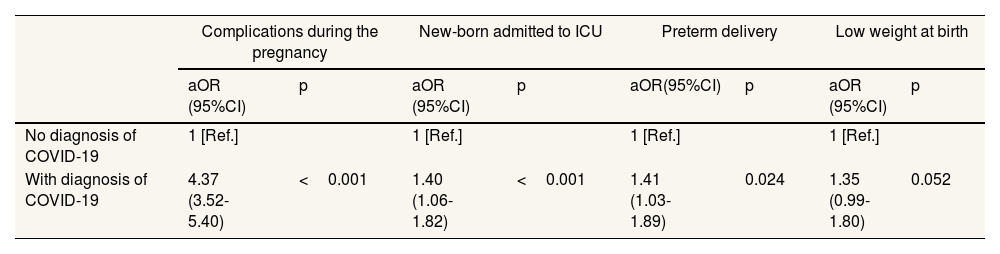

Table 3 shows the results of the logistic regression models by outcomes. Women with COVID-19 had a 4.37 times higher risk (OR: 4.37; 95%CI: 3.52-5.40) of having complications during pregnancy than women without COVID-19. In addition, diagnosis of COVID-19 during pregnancy increased the risk of preterm birth (OR: 1.41; 95%CI: 1.03-1.89), newborns admitted to the NICU (OR: 1.40; 95%CI: 1.06- 1.82) and low birth weight (OR: 1.35; 95%CI: 0.99-1.80), although this one was not significant.

Adjusted odds ratio (and 95% confidence interval) of the relationship between maternal and neonatal outcomes among women with a positive diagnosis of COVID-19 compared to women without a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19.

| Complications during the pregnancy | New-born admitted to ICU | Preterm delivery | Low weight at birth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR(95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | |

| No diagnosis of COVID-19 | 1 [Ref.] | 1 [Ref.] | 1 [Ref.] | 1 [Ref.] | ||||

| With diagnosis of COVID-19 | 4.37 (3.52-5.40) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.06-1.82) | <0.001 | 1.41 (1.03-1.89) | 0.024 | 1.35 (0.99-1.80) | 0.052 |

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; NICU: neonatal intensive care unit.

In the sensitivity analysis adjusted for additional confounders (COVID-19 waves) and excluding mothers who had twins, the association of having COVID-19 during pregnancy and the outcomes analysed was found to be similar to that reported in the main results (see Table IV in online Appendix).

DiscussionThe results of this study show that women with COVID-19 in Catalonia in 2020 had a greater risk of complications during pregnancy with a higher probability that their babies would be admitted to NICU and be premature.

Fifty-five point nine percent of pregnant women with COVID-19 became diagnosed in the second wave. This may be due to different elements: on the one hand, government relaxed COVID-19 control measures, students returned to school and universities, companies called employees to return to office, and people began to increase the use of public transport. On the other hand, the greater availability of diagnostic tests and mass screening made it easier to detect cases. Also the higher rate of cases in the whole population would have led a higher number of infections among pregnant women.16 The third wave coincided with the winter holiday season that in Spain begins in early December, when people increased family and friends’ gatherings.

Most of the pregnant women with COVID-19 lived in urban areas, had a low socioeconomic status and were foreign nationals. These results are consistent with published studies that describe the greater risk of getting COVID-19 to various causes such as overcrowding in homes, poor ventilation and inadequate disinfection measures. People who are more disadvantaged may also use more public transport and hold more precarious jobs which cannot be developed home-based.17–19

Three out of four pregnant women in Catalonia in 2020 gave birth in the public hospitals, a figure similar to previous years.12 This percentage was higher in women with COVID-19 (88.9% with COVID-19 vs. 73.2% without COVID-19). This might be due to socioeconomic and socio-cultural factors. Some studies suggest that there are differences in access to the healthcare system between the local and migrant populations.20 More than 60% of the women with COVID-19 were foreign nationals (33% of which were from Morocco and 10% from Honduras). These findings are in line with other works that suggest various reasons for these disparities, including social determinants of health, comorbidities and potentially genetic influences.21

Women with COVID-19 are at higher risk of complications during pregnancy than women without COVID-19 (24.7% vs. 6.2%), and the most frequent complication were gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, eclampsia and HELLPS syndrome. Other researchers found similar results with percentages of complications in women with COVID-19 ranging from 19.7% to 34.6%.22–24 Some publications report that pregnant women may have a greater risk of complications in the third trimester of pregnancy than in early pregnancy.21,25,26 Our study shows that 79.2% of women with COVID-19 were diagnosed in the third trimester of pregnancy or at the time of delivery. These results are consistent with those of Salem et al.,27 who reported that the third trimester of pregnancy appears to be the most vulnerable period for infection. However, in our case the difference between the proportion of women diagnosed in the first and second trimester and the proportion of women diagnosed in the third trimester and at the time of delivery could it be due to different exposure: there were less women exposed during the first and second trimester, especially those who gave birth during the first months of the pandemic because of the restriction measures and the reduce mobility. Moreover, during the first months of the pandemic (March-June) there was a lower capacity of testing. Also, protocols were continuously changing during 2020. The generalized extension of testing to symptomatic or asymptomatic people attending at hospitals only become from July 2020.28

Prematurity is associated with increase perinatal mortality and long-term morbidity.29 Our results show that babies born to women with COVID-19 had a 50% higher risk of preterm birth. Allotey et al.30 reported similar findings in a systematic review of pregnant women with COVID-19 in which their babies were at greater risk of preterm birth (OR: 1.47; 95%CI: 1.14-1.91). Although we could not differ iatrogenic from spontaneous prematurity, other authors found that iatrogenic preterm births were more frequent in babies born to women with COVID-19 due to maternal complications or foetal compromise.29,31

Babies born to women with COVID-19 had a higher frequency of low birth weight (7.6%) than babies born to women without COVID-19 (6.9%), although there was no statistical difference. While some authors also revealed no significant relationship between low birth weight and pregnant women with COVID-19,32,33 other authors reported an increased risk of low birth weight in babies born to mothers with COVID-19 and indicate that could be a confounded by a high incidence of preterm birth.23,25,34

A total of 10.4% of babies born to mothers with COVID-19 were admitted to NICU with a 41% higher risk of admission than babies born to mothers without COVID-19. We observed higher rates of NICU in neonates from non-Spanish women with COVID-19 than from Spanish women. This is a matter of concern and should be investigated further. Similar findings have been observed in other studies.25 A study in Spain also found an increased risk of NICU admission for babies born to women with COVID-19 (OR: 4.62; 95%CI: 2.43-8.94).35 While there are studies that found that prematurity and respiratory distress were reasons for admission to NICU, other studies suggest preventable reasons.23,25,36,37

The strength of this study is the use of administrative data that included all the population-based data of an entire region. Another strength is that include Spanish and migrant population. Moreover, the availability of a computerised registry (TAGA-COVID-19) of all diagnosed cases of COVID-19 in Catalonia made it possible to gather data on live births and pregnant women with COVID-19. The database matching from the two registers to develop this study has made it possible to identify areas of improvement in both registers. Further, this study can contribute evidence about effects of COVID-19 in the health of women and their babies during the pandemic.

There are some limitations. First, data collection was affected by the healthcare workload during the pandemic, which led to loss of information such as the type of delivery (caesarean or vaginal), where studies have found an increase in caesarean incidence in women with COVID-19.25 Second, at the beginning of the pandemic, the COVID-19 diagnosis was affected by the lack of test kits. Consequently, there might have been women who had been infected but were not diagnosed. However, other studies had the same limitations and our results are similar.9 Third, we had not information about underlying medical conditions in pregnant women, although literature reported that pregnant women with pre-existing comorbidities were at increased risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes and adverse birth outcomes.26,30 To reduce possible bias, it is necessary future studies including this information. Another limitation of the study was the amount of missing information on pregnancy complications, which made difficult us to classify them. This highlighted the need of improving reported information for future research of pregnancy complications associated with COVID-19 as well as other infections. Finally, although we did not report maternal mortality, there are studies that associate a higher maternal mortality in pregnant women with COVID-19, especially if they were from ethnic minorities or had underlying medical conditions.9,30

In conclusion, this study shows that pregnant women are more vulnerable to COVID-19 as they have a higher risk of complications during pregnancy while there is also an impact on their babies such as a greater risk of admission to NICU and preterm birth. These findings highlight the need to reinforce reported routine data to better monitoring pregnant women and newborns as a vulnerable group to COVID-19.

Availability of databases and material for replicationAuthors are not owner of the data. In order to request the database used in this study, contact with Pilar Ciruela (pilar.ciruela@gencat.cat) or Maria José Vidal (mjose.vidal@gencat.cat).

Pregnant women are considered an important vulnerable population group to respiratory virus infection, including SARS-CoV-2. Moreover, they have a higher risk of developing complications during pregnancy and their newborns were more likely to be admitted to neonatal intensive care unit and have prematurity.

What does this study add to the literature?This study use administrative data that included all the population-based data of an entire region to produce evidence and to offer an overview about effects of COVID-19 in the health of women and their babies during the pandemic in 2020.

What are the implications of the results?This study shows the effects of COVID-19 on pregnant women and their newborns. These findings highlight the need to reinforce reported routine data to better monitoring pregnant women and newborns as a vulnerable group to infections.

Lucero Aída Juárez Herrera y Cairo.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsAll authors have made substantial contribution to the whole of the manuscript. P. Ciruela was the manager leadership. P. Ciruela, J. Mendioroz and M.J. Vidal thought on the conceptual design of the matching of database to research and produce evidence about effects of COVID-19 in the heath of women and their babies. N. Sala and M.J. Vidal debugged and filtered the variables of the registry of newborns. N. Sala and E. Martínez worked in methodology section. S. Mendoza debugged and filtered the variables of the TAGA-COVID-19 and made the matching of the two database with an identification variable. E. Martínez analysed and made the first step in data interpretation. She made the draft of results section with M. Jané and M.J. Vidal. Then all the authors contributed in the interpretation of data. M.J. Vidal, N. Sala, P. Ciruela and J. Mendioroz made the drafting introduction and discussion section. Then, M. Jané made a critical review. All the authors made a critical reviewed, discussed and approved the final version.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestsNone.