To describe the objectives, the methodological approach, the response rate of the Genetic, Environmental and Life-style Factors Study in Castilla y León (Spain).

MethodThe Health Sentinel Network studied a sample of long-lived individuals aged 95 or more (LLI). The study included biological samples processed with the Global Screening Array v3.0 that contains a total of 730,059 markers. Written consent was obtained before the examination.

ConclusionsThe LLI contacted were 944, and 760 were completed studied. The 87.4% of LLI were born in Castile and Leon and only 1% were non-native of Spain. Severe cognitive impairment was declared in 8.1% of men and 19.2% of women. Genotyping was performed in 739 LLI, the 78.3% of the contacted sample. Family doctors and nurses achieve high participation in population-based studies. DNA samples were taken from 94% of fully studied LLI, and 100% of these samples where successfully genotyped.

Describir los objetivos, la metodología y la respuesta del estudio «Factores genéticos, ambientales y de estilo de vida asociados a la longevidad en Castilla y León» (España).

MétodoLa Red Centinela Sanitaria estudió una muestra de personas longevas de 95 y más años de edad. Se pidió el consentimiento informado y se tomaron muestras biológicas para genotipificación, que fueron procesadas con el Global Screening Array v3.0 que contiene 730.059 marcadores.

ConclusionesFueron contactados 944 longevos y 760 completaron el estudio. El 87,4% de los longevos habían nacido en Castilla y León, y solo el 1,5% no eran naturales. El 8,1% de los hombres y el 19,2% de las mujeres presentaban un deterioro cognitivo grave. Los médicos de familia y las enfermeras consiguen una alta participación y una buena calidad de la información en estudios de base poblacional. Se tomaron muestras de ADN en el 94% de los longevos y el 100% fueron genotipificadas con éxito.

Longevity is considered a personal achievement and social success but also a challenge for the health and welfare systems. The study of exceptional human longevity addresses the identification of genetic and environmental factors related to both length and quality of life. It has also been emphasized that translations in research on aging should be in the agenda priorities of any public health policy in countries with aged populations.1

Genetic studies in this field, are based on small number of candidate gene analyses2–4 and more recently, are expanded to larger and more complex whole-genome analyses.5–7.

As the result, several so-called “longevity genes” have been identified to date, although confirmatory studies in larger cohorts and from different populations are required. In addition, the interactions between these “longevity genes” with environment and life-style factors are still unexplored.

The study of very old people is conditioned by their cognitive status, disabilities and their short life expectancy that limits both the information and the follow-up. The studies in Spanish population have been mostly carried out in limited series of cases,8 focused in healthy ageing9 or in particular diseases, like Alzheimer's disease.10

The increase in the population of very old people is remarkable worldwide. In Spain, the Spanish Statistical Office predicts around 100,000 centenarians by the year 2050.11 In Castile and Leon, 3053 men y 8599 women were ≥95 years old, which represented the 0.48% of the total population in 2018.

This project (LONGECYL Study) aims to fully describe a representative population of nonagenarians-centenarians from the region of Castile and Leon from both the genetic and epidemiological point of view, in order to identify the genetic background, environmental, life-style and socioeconomic factors related to their health status. In this article, we will describe the general objectives, the methodological approach, the response rate as well as the main characteristics of the studied population.

MethodWe designed a collaborative study among the Health Sentinel Network of Castile and Leon (HSNCyL) (Valladolid), the National DNA Bank (BNADN, University of Salamanca; www.bancoadn.org) and the Human Genotyping Unit at the Spanish National Cancer Research Center (GU-CNIO) in Madrid, (1) to describe the health of the regional population aged ≥95, (2) to identify the environment and life-style factors associated with their health status and quality of life, (3) to confirm/rule out already described genetic risk factors associated with longevity in the Spanish population, (4) to identify novel genetic risk factors related to longevity, (5) to study the interaction among genetic and non-genetic factors, and (6) to assess the epigenetic profile related to longevity.

The HSNCyL is a health information system made up of epidemiologist and healthcare professionals at primary care units, with a wide experience in surveillance and epidemiological research in different topics,12–14 working together within well-defined areas comprising a representative cohort of the population living in the region.15–17

Sample and proceduresThe sentinel population covered by the HSNCyL in 2019 was 186,123 inhabitants. We identified 1298 long-lived individuals (LLI) whose 95th or higher birthday was between the 1st of March 2019 and 28th February 2020, which represented 0.70% of the sentinel population (73% female; 76.6%<98, 14.9% between 98 and 99, and 8.5% ≥100 years old).

The sentinel doctors and nurses received a list of the eligible population with their address and telephone number. The persons, their relatives or nursery home responsible, in case of residents in institutions, were contacted to explain the study's main objectives and to arrange a medical appointment to describe the research in detail and sign the written informed consent by themselves or their tutors.

A blood sample was drawn into EDTA-collection tube or, alternatively, a saliva sample was collected from every voluntary donor, when venipuncture was not clinically recommended. Thereafter, biological samples were immediately sent to the BNADN facilities by refrigerated express transport in a category B biological substance biosafety (UN3373) shipping box. DNA was obtained by a salting out (manual) method, including two additional steps of proteinase K digestion and RNAsa A treatment, in the case of saliva samples. Extracted DNA was assessed for quantity and quality, using spectrophotometry and agarose gel electrophoresis, respectively. If enough blood sample volume was available, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were obtained by Ficol-paque gradient centrifugation and viable cells were stored in liquid nitrogen for subsequent analysis.

The sentinel doctors and nurses filled a standard interview questionnaire (with or without the help of a relative) that included social and demographic information, clinical and anthropometric data, medical background, the 3-level version of EQ-5D,18 life-style habits (including diet), working life and family health and demographic history (see online Supplementary material, Appendix 1).

DNA samples were sent to the GU-CNIO and quantified using Picogreen® method (Invitrogen). A total amount of 250 ng of DNA was processed according to the Infinium HTS assay Protocol (Part # 15045738 Rev. A, Illumina™), including amplification, fragmentation and hybridization using the Global Screening Array v3.0. This array contains a total of 730,059 markers and was scanned on an iScan platform (Illumina™). Clustering and genotypes calling were performed using Genome Studio v2.0.4 (Illumina™, San Diego, U.S.A.).

Ethical considerationsIn March 2018, the Clinical Research Ethical Committee approved the protocol and in November 2018, the HSNCyL Steering Committee included the study in the 2019 annual program.

Doctors and nurses were instructed to inform the selected person, their relatives or caregivers about the objectives of the study, the procedures of the survey, the clinical examination and the blood sample. The person or legal guardian were asked to sign the written consent for the survey, the examination, the access to their medical record and the blood sample. They should also sign the future contact acceptance for a follow up or for receiving relevant clinical results.

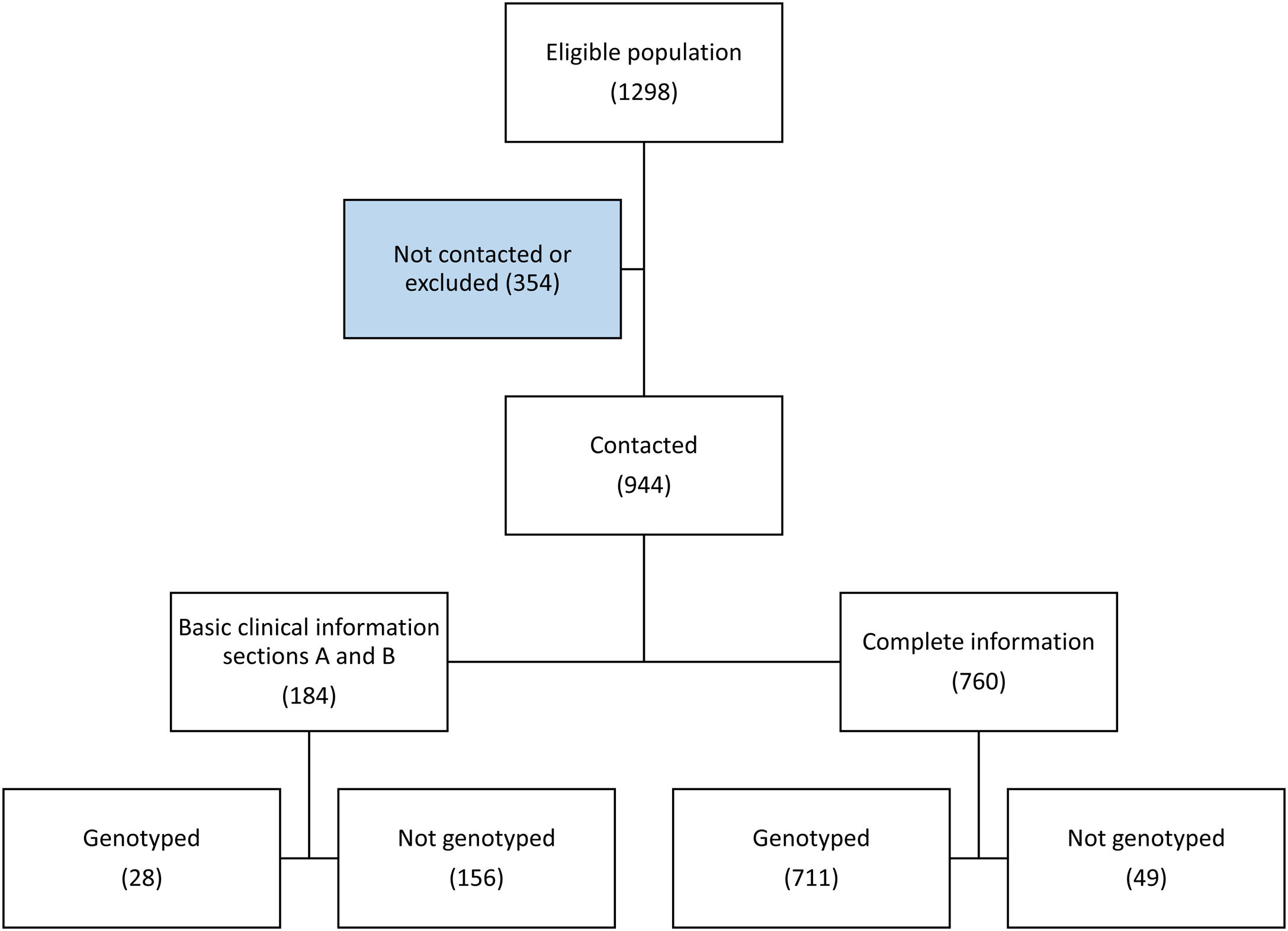

DiscussionFrom the 1298 LLI eligible for the study, 354 could not be contacted or were excluded because of death before the survey (65), declined to participate in the study (43), others showed advanced cognitive impairment (5), some others were not located or not accessible (219) or other causes (22). The final sample was constituted of 944 LLI, 72.7% of the eligible population, from which 760 were fully studied and interviewed. In 184, only vital status and clinical information was obtained from the patient, relatives, caregiver and medical records (fig. 1).

Females represented 72.5% (non-statistical differences with 74.3% of the eligible population), and age distribution showed 77.1% below 98 years old and 7.5% ≥100 (non- statistical differences with the eligible population). Blood or saliva samples were obtained, and genotyping was performed in 739 LLI (78.3% of the studied sample).

Most of the studied LLI were born in Castile and Leon and only 1% were non-native of Spain. Almost one out three were institutionalized and between 40-45% were cared by their offspring. Around 5% of LLI lived alone without any caregiver, more women than men (table 1).

Demographic and main health status of long life individuals by sex.

| Male | Female | All | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (260) | % | N (684) | % | N (944) | % | |

| Age group, years | ||||||

| 95-97 | 213 | 81.9 | 515 | 75.3 | 728 | 77.1 |

| 98-99 | 36 | 13.8 | 109 | 15.9 | 145 | 15.4 |

| 100 and more | 11 | 4.2 | 60 | 8.8 | 71 | 7.5 |

| Place of birth | ||||||

| Castile and Leon (Spain) | 234 | 90.0 | 591 | 86.4 | 825 | 87.4 |

| Rest of Spain | 16 | 6.2 | 63 | 9.2 | 79 | 8.4 |

| Other countries | 1 | 0.4 | 8 | 1.2 | 9 | 1.0 |

| Unknown | 9 | 3.5 | 22 | 3.2 | 31 | 3.3 |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| At own home with family | 117 | 45.0 | 227 | 33.2 | 344 | 36.4 |

| At own home alone | 30 | 11.5 | 94 | 13.7 | 124 | 13.1 |

| At family home | 24 | 9.2 | 111 | 16.2 | 135 | 14.3 |

| Nursing home | 85 | 32.7 | 236 | 34.5 | 321 | 34.0 |

| Unknown | 4 | 1.5 | 16 | 2.3 | 20 | 2.1 |

| Marital/civil status | ||||||

| Single | 25 | 9.6 | 59 | 8.6 | 84 | 8.9 |

| Married/partner | 87 | 33.5 | 31 | 4.5 | 118 | 12.5 |

| Widow/er | 138 | 53.1 | 553 | 80.8 | 691 | 73.2 |

| Separated/divorced | . | . | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Unknown | 10 | 3.8 | 40 | 5.8 | 50 | 5.3 |

| Caregiver | ||||||

| Without caregiver | 15 | 5.8 | 27 | 3.9 | 42 | 4.4 |

| Partner | 17 | 6.5 | 1 | 0.1 | 18 | 1.9 |

| Offspring | 103 | 39.6 | 293 | 42.8 | 396 | 41.9 |

| Formal caregiver | 32 | 12.3 | 104 | 15.2 | 136 | 14.4 |

| Institution | 85 | 32.7 | 236 | 34.5 | 321 | 34.0 |

| Unknown | 8 | 3.1 | 23 | 3.4 | 31 | 3.3 |

| Barthel Index | ||||||

| Independency | 15 | 5.8 | 17 | 2.5 | 32 | 3.4 |

| Slight dependency | 14 | 5.4 | 23 | 3.4 | 37 | 3.9 |

| Moderate dependency | 87 | 33.5 | 174 | 25.4 | 261 | 27.6 |

| Severe dependency | 58 | 22.3 | 199 | 29.1 | 257 | 27.2 |

| Total dependency | 37 | 14.2 | 177 | 25.9 | 214 | 22.7 |

| Unknown | 49 | 18.8 | 94 | 13.7 | 143 | 15.1 |

| Cognitive impairment | ||||||

| No | 116 | 44.6 | 236 | 34.5 | 352 | 37.3 |

| Slight | 64 | 24.6 | 150 | 21.9 | 214 | 22.7 |

| Moderate | 37 | 14.2 | 109 | 15.9 | 146 | 15.5 |

| Severe | 21 | 8.1 | 131 | 19.2 | 152 | 16.1 |

| Unknown | 22 | 8.5 | 58 | 8.5 | 80 | 8.5 |

Only 3.4% of the LLI were completely independent for their basic activities of daily living, and 14.2% of men and 25.9% of women were absolutely dependent. Severe cognitive status was quite well preserved in the sample cohort, with 44.6% of men and 34.5% of women without dementia. Severe cognitive impairment was declared in 8.1% and 19.2%, respectively.

Primary care has been proved as the best place for getting their life trajectory and health background in population-based epidemiological studies.13,19,20 Family doctors and nurses are close to their patients and families, and have a special relationship to recruit people and establish the necessary confidence bond to take part in a research project.

Health Sentinel Networks show a large methodological experience in epidemiological studies where accessibility to general population can be compromised.12,21–23. Research field work implemented in primary health care obtains high participation coverage and high quality of information.19,24

This study was particularly difficult because of the age of the reference population and the assumed limited life expectancy. Some previous study designs25,26 were reviewed to adapt the methodological approach to this particular scenario.

The high mortality rate in this aged cohort forced us to reduce the time of the field work. Even so, 65 person died before they could be studied.

The number of subjects who declined to participate within the study represents only 5%, and most of the LLI not studied were due to change of residence or death before their 95th birthday. We obtained clinical and demographic information from more than 70%.

The difficulties of working with a small, aged, dependent population with potential cognitive impairment was compensated by the confidence, closeness, approachability and wisdom of the Sentinel Network family doctors and nurses, proving to be the ideal reporters for this research. Severe or total dependence was observed in half of the studied population, whereas 60% had a fairly well-preserved cognitive function.

We obtained a high number of DNA samples (94% of fully studied LLI), and 100% of these samples where successfully genotyped. The interdisciplinary collaboration among HSNCyL, BNADN, GU-CNIO has been the key for this exceptional response rate and subsequent laboratory achievement.

Editor in chargeCarlos Álvarez Dardet.

Authorship contributionsAll authors, provided substantial contributions to the global project, researched the literature, and define the objectives of this article. T. Vega wrote the article; T. Vega, F. Hilario and M. Pérez-Caro managed the field work and quality control; A. González-Neira, R. Núñez-Torres and R.M. Pinto completed the first draft and reviewed and/or edited the final manuscript. All authors discuss the content before submission.

AcknowledgementsTo the Sentinel Family doctors and Nurses, for their excellent field work. To the provincial epidemiology sections, for their logistic support. To the people, relatives and caregivers, who consented to take part in this study.

FundingThis study has been financed by the “Acción Estratégica de Salud” (Strategic Health Action). ISCIII. PI19-00991 and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Conflicts of interestNone.

T. Vega, A. Ordax, J. Lozano, F. Hilario, L. Estévez, R. Álamo, M.J. Alonso (Dirección General de Salud Pública, Consejería de Sanidad, Valladolid); A. González-Neira, R. Nuñez-Torres, G. Pita (Unidad de Genotipado Humano-CEGEN, Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Oncológicas, Madrid); E. Arrieta, A. Díaz (Gerencia Regional de Salud, Consejería de Sanidad de Castilla y León); A. Santos-Lozano (i+HeALTH, European University Miguel de Cervantes, Valladolid); J. Yáñez (Servicio Territorial de Sanidad, Burgos); M. Pérez-Caro, R.M. Pinto, M. Márquez, M. Morante (Banco Nacional de ADN, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca).