To analyze the factors associated with sexual risk behavior in adolescent girls and boys in order to plan future school health interventions.

MethodsA cross-sectional study with two-stage cluster sampling that included 97 schools and 9,340 students aged between 14 and 16 years old was carried out in 2005-2006 in Catalonia (Spain). For the survey, a self-administered paper-based questionnaire was used. The questionnaire contained items on sociodemographic variables, use of addictive substances and mood states, among other items. These variables were tested as risk factors for unsafe sexual behavior.

ResultsThis study included 4,653 boys and 4,687 girls with a mean age of 15 years. A total of 38.7% of students had had sexual relations at least once and 82.3% of boys and 63.0% of girls were engaged in sexual risk behaviors. The prevalence of sexual relations and risk behaviors was generally higher in boys than in girls, independently of the variables analyzed. Boys had more sexual partners (P<.001) and used condoms as a contraceptive method less frequently than girls (P<.001). Foreign origin was related to unsafe sexual activity in both genders. Alcohol consumption was also a risk factor in boys.

ConclusionsSexual risk behaviors among adolescents in Catalonia are higher in boys than in girls. Factors related to unsafe sexual activity in boys were foreign origin and alcohol consumption. In girls only foreign origin was a significant risk factor.

El objetivo de este estudio es analizar aquellos factores relacionados con conductas sexuales de riesgo en chicos y chicas para poder plantear futuras intervenciones.

MétodosEstudio transversal basado en un muestreo por conglomerados bietápico, que incluía 97 escuelas y 9.340 estudiantes de entre 14 y16 años, llevado a cabo en Cataluña durante 2005-2006. La información se recogió mediante una encuesta autoadministrada que incluía, entre otras, variables sociodemográficas, uso de sustancias adictivas y estado de ánimo de los adolescentes. Estas variables fueron analizadas como factores de riesgo de conducta sexual insegura.

ResultadosEl estudio incluyó 4.653 chicos y 4.687 chicas con una edad media de 15 años. El 30,7% de los estudiantes habían tenido al menos una relación sexual. El 82,3% de los chicos y el 63% de las chicas tenían un aumento de riesgo de experimentar una relación sexual insegura. La prevalencia de relaciones sexuales y de relaciones sexuales de riesgo era en general mayor en los chicos que en las chicas, independientemente de la variable analizada. Los chicos tenían más parejas sexuales (p<0,001) y habían utilizado el condón menos frecuentemente que las chicas (p<0,001). El factor que estaba relacionado con una conducta insegura en ambos sexos era el origen inmigrante, y en los chicos también el consumo de alcohol.

ConclusionesLas conductas de riesgo sexual entre los adolescentes catalanes son más elevadas en los chicos. Los factores relaciondos con una actividad insegura en los chicos son ser de origen inmigrante y el consumo de alcohol. En las chicas sólo ser de origen inmigrante resultó ser un factor de riesgo.

Adolescence is a phase with rapid changes when adolescents feel secure, making it easy for them to participate in activities considered risky such as sexual relations.1 This is when a higher probability of sexual risk behaviour is present,2,3 and therefore a higher risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections.4 Recently, the incidence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among adolescents has been increasing.5 In the US, three million adolescents are infected with a STI each year.6 In Catalonia, although the most affected age groups by the STIs submitted to notification are in the 25-44 years old age range, an increase in notified young people's cases (15-24 years) was observed in 2006.7 In 2006, females younger than 25 years accounted for 22.9% of all STI declarations and males of the same age group accounted for 9.2% of all declarations. While the mandatory declaration system does not completely reflect what is occurring in our population, it is practically the best tool we have to understand tendencies.

Gender differences in norms for sexual behaviour exist and factors associated with sexual relations may differ by sex. In studies by Faílde JM et al. and Teva I et al.8,9 it was found that, in general, males tend to have more sexual partners than females, and they also tend to use condoms less frequently than women during vaginal intercourse. In other words, at any given adolescent age, risky sexual behaviour is more likely among males than among females.10 However, little research has been conducted on socio-demographic factors or the effect of addictive substances on sexual behaviour, especially in relation to gender; therefore, when implementing intervention it is necessary to take into account sexual behaviour patterns, socio-demographic factors and gender.

Sexual risk behaviour are preventable by a coordinated effort between families, schools, health and education agencies and community organizations.11,12 So as to learn more about the health of Catalan adolescents, the Catalan Government promoted the Health and School Survey amongst 14-16 year old students.

The aim of the study was to analyse those factors associated to sexual risk behaviour in males and females in order to plan future school health interventions.

MethodsThe data obtained from the survey “Health and School” promoted by the Department of Health of the Catalan Government within the framework of the Healthy Schools Program Initiative have been analysed. The survey took place between February and June during the school year 2005-2006, with the objective to establishing the prevalence of health risks among students in the third and fourth years of Compulsory Secondary Education in Catalonia.

A cross-sectional study using a two-stage sampling of the schools was carried out. During the first stage, the primary sampling unit was the school, which had been previously stratified in 10 Health Care Regions with non-proportional sampling. Within each Health Region it was stratified by type of school according to the funding (public or private). It was a proportional to size sampling. In the second stage all the students of the third and four-degree classes from these schools were selected.

The sample size was calculated based on a sampling frame of 978 schools with an estimated 125,389 students (according to data available from the school year 2004-2005). The sample size was calculated independently for each stratum. Given the cluster design, an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.0213-17 was assumed, the average number of students per school per Health Regions, a 50% event rate, an alpha two-tailed significance level of 0.07 in the small Health Regions, an alpha two-tailed of 0.05 in the others ones, and a statistical power of 80%. To reduce the effect of possible non-participation of some of the schools selected in the sample size, the sample size was increased by 20%. Under these assumptions, 111 schools were selected with an estimated population of 13,165 students between 14 to 16 years old. Finally, we obtained 9,340 correctly answered questionnaires, which represent an estimated response rate of 70.9%.

Participation was voluntary for both the schools and the students. Each school had to give its informed consent before administering the questionnaire.

The questionnaire guaranteed the anonymity of the students and it was largely based on: the questionnaire of the Barcelona Public Health Agency “Risk factors in school children (FRESC)”,18 a series of new questions agreed on by a group of experts from the Department of Health, a bibliographical review19,20 and other national21,22 and international questionnaires.23

A pilot test of the pre-final version in identical conditions to those that would be used in the real survey was conducted in two groups of students.

The final questionnaire included 94 questions, which collected information about the abuse of addictive substances, mood states, accidents and injuries, diet and sexual habits, among others. Thirty-three of the questions measured aspects relating to the sexual behaviour of the students.

The sexual behaviour questions collected information regarding: If they had experienced sexual relations at least once, either oral, vaginal or anal; the method of contraception used in the last 3 months: no sexual intercourse, pills, condoms, diaphragm, intrauterine device, rhythm method, spermicides, coitus interruptus, others and no method; access to condoms: this refers to if they have ever bought condoms (yes/no); frequency of sexual relations: once, rarely, few times per month, few times per week and every day; number of sexual partners: 1, 2, 3,4, 5, 6 or more; the use of the morning after pill at some time: yes/no; reported pregnancy: yes/no/does not know; number of times advice was solicited from health professional related to sexuality: never, before first sexual intercourse, <1 month after first sexual relation, 1-3 months after, 3-6month after, > 6 months after and > 1year after; frequency of condom use during sexual intercourse: always, almost always, 50% of times, few times and never; refused sexual intercourse without condom: yes/no.

Other variables in addition to those related to sexual behaviour were considered in the analysis. We collected information regarding sociodemographic, individual and school characteristics such as: age; gender; characteristics of the nuclear family as has both parents, has only father/mother, or does not have either parent; foreign origin, a student is considered foreign or of foreign origin if either he/she or one of his/her parents was been born outside Spain; general health status, the adolescent's perception of his/her general health, classified as excellent, very good and good against low-average or poor; academic performance, the adolescent's perception of his/her academic performance compared to his/her peers, classified as high, medium or low; type of school funding categorized as public/ private and mood states considered as either having 3 or more negative mood states, or not having them (tiredness, insomnia, sadness, despair, anxiety and boredom). Finally, addictive substances were also considered for the analysis. Cannabis, cigarettes and alcohol were included as dichotomous variables (yes/no use in the previous month).

Considering that the objective of the study was to analyse the factors associated with risky sexual behaviour, a global composite variable that would reflect this risk was suggested according to recent practices of using composite measures of sexual risk taking.24,25 The creation of a composite variable that provided a comprehensive view of overall sexual risk resulted more realistic than considering each measure separately. To obtain this global measure of risky health behaviour, experts in STI prevention among youths selected a group of items that would be the basis of the composite variable. These items were: number of partners: having 3 or more than 3 partners was considered risk behaviour; admitting to having sexual intercourse without the use of a condom as opposed to not having sexual intercourse in the past three months or having sexual intercourse using a condom in the past three months; frequency of use of the condom: always versus almost always, 50% of times, few times and never; not having refused penetration without a condom, either because they did no have it or because the sexual partners refused to use it.

If the student gave a positive answer to any of these questions, which were considered unsafe, he/she was classified as an adolescent with sexual risk behaviour. When none of these behaviour patterns were present the adolescent was classified within the category of safer sex.

Statistical methods for analyzing data for complex samples were used. Data were weighted to adjust for probability of selection. To account for sample design effects (stratification, clustering and weighting), we used the svy commands with the jackknife method for variance estimation (Stata User's Guide: Release 9. Chapter: Survey Data. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2005). The procedures to estimate parameters are design-based.

Thus, in order to test the independence of variables and gender, a Chi-Square test or t-test was used.

An unconditional logistic regression model was used to estimate the factors associated with the existence of sexual risk behaviour. We have used the purposeful selection method to select a subset of covariates to include in the final logistic regression model.26 The authors checked for confounders and interactions among the independent variables (age, citizenship, health status, family structure, mood state, school funding, alcohol last month, smoking last month, cannabis last month and academic performance). We tested the significance of the interaction coefficients using the adjusted Wald test. These analyses were conducted with Stata/SE version 9.1 and SPSS statistical package for Windows version 13.0.

ResultsThe study included 49.8% of males. The mean age was 15.24 years old (CI 95% 15.21-15.28). Of all students, 30.5% had sexual relations at least once, 33.6% of males and 27.4% of females (P<.001).

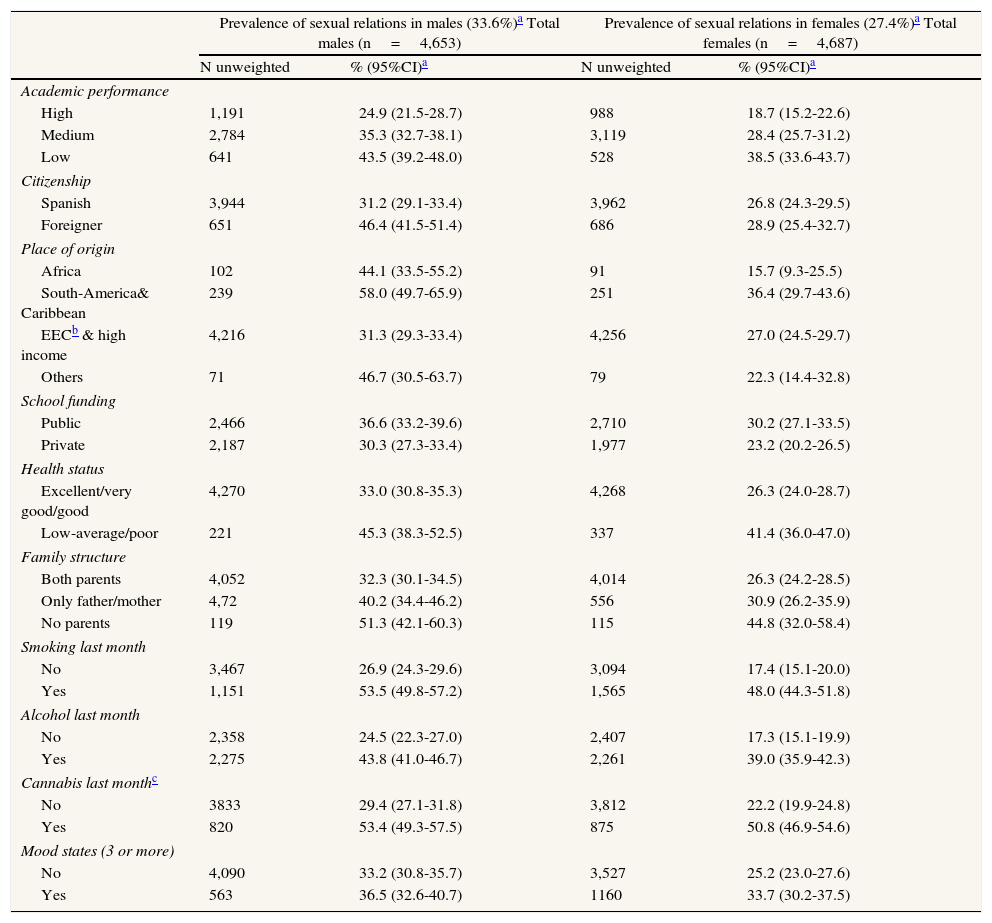

The prevalence of sexual relations and risky sexual relations for different prognostic factors is shown in Table 1 and Table 2. In relation to the prevalence of sexual relations among males, higher percentages were observed in the following categories: foreigner, South Americans, those with low academic performance, those attending schools with public funding, those with regular or poor health status, those without parents, smokers, consumers of alcohol, cannabis users and in those that had three or more mood problems. In females, although the prevalence of sexual relations was lower than males, a similar pattern was observed.

Prevalence of sexual relations for each category of the independent variables, stratified by gender.

| Prevalence of sexual relations in males (33.6%)a Total males (n=4,653) | Prevalence of sexual relations in females (27.4%)a Total females (n=4,687) | |||

| N unweighted | % (95%CI)a | N unweighted | % (95%CI)a | |

| Academic performance | ||||

| High | 1,191 | 24.9 (21.5-28.7) | 988 | 18.7 (15.2-22.6) |

| Medium | 2,784 | 35.3 (32.7-38.1) | 3,119 | 28.4 (25.7-31.2) |

| Low | 641 | 43.5 (39.2-48.0) | 528 | 38.5 (33.6-43.7) |

| Citizenship | ||||

| Spanish | 3,944 | 31.2 (29.1-33.4) | 3,962 | 26.8 (24.3-29.5) |

| Foreigner | 651 | 46.4 (41.5-51.4) | 686 | 28.9 (25.4-32.7) |

| Place of origin | ||||

| Africa | 102 | 44.1 (33.5-55.2) | 91 | 15.7 (9.3-25.5) |

| South-America& Caribbean | 239 | 58.0 (49.7-65.9) | 251 | 36.4 (29.7-43.6) |

| EECb & high income | 4,216 | 31.3 (29.3-33.4) | 4,256 | 27.0 (24.5-29.7) |

| Others | 71 | 46.7 (30.5-63.7) | 79 | 22.3 (14.4-32.8) |

| School funding | ||||

| Public | 2,466 | 36.6 (33.2-39.6) | 2,710 | 30.2 (27.1-33.5) |

| Private | 2,187 | 30.3 (27.3-33.4) | 1,977 | 23.2 (20.2-26.5) |

| Health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 4,270 | 33.0 (30.8-35.3) | 4,268 | 26.3 (24.0-28.7) |

| Low-average/poor | 221 | 45.3 (38.3-52.5) | 337 | 41.4 (36.0-47.0) |

| Family structure | ||||

| Both parents | 4,052 | 32.3 (30.1-34.5) | 4,014 | 26.3 (24.2-28.5) |

| Only father/mother | 4,72 | 40.2 (34.4-46.2) | 556 | 30.9 (26.2-35.9) |

| No parents | 119 | 51.3 (42.1-60.3) | 115 | 44.8 (32.0-58.4) |

| Smoking last month | ||||

| No | 3,467 | 26.9 (24.3-29.6) | 3,094 | 17.4 (15.1-20.0) |

| Yes | 1,151 | 53.5 (49.8-57.2) | 1,565 | 48.0 (44.3-51.8) |

| Alcohol last month | ||||

| No | 2,358 | 24.5 (22.3-27.0) | 2,407 | 17.3 (15.1-19.9) |

| Yes | 2,275 | 43.8 (41.0-46.7) | 2,261 | 39.0 (35.9-42.3) |

| Cannabis last monthc | ||||

| No | 3833 | 29.4 (27.1-31.8) | 3,812 | 22.2 (19.9-24.8) |

| Yes | 820 | 53.4 (49.3-57.5) | 875 | 50.8 (46.9-54.6) |

| Mood states (3 or more) | ||||

| No | 4,090 | 33.2 (30.8-35.7) | 3,527 | 25.2 (23.0-27.6) |

| Yes | 563 | 36.5 (32.6-40.7) | 1160 | 33.7 (30.2-37.5) |

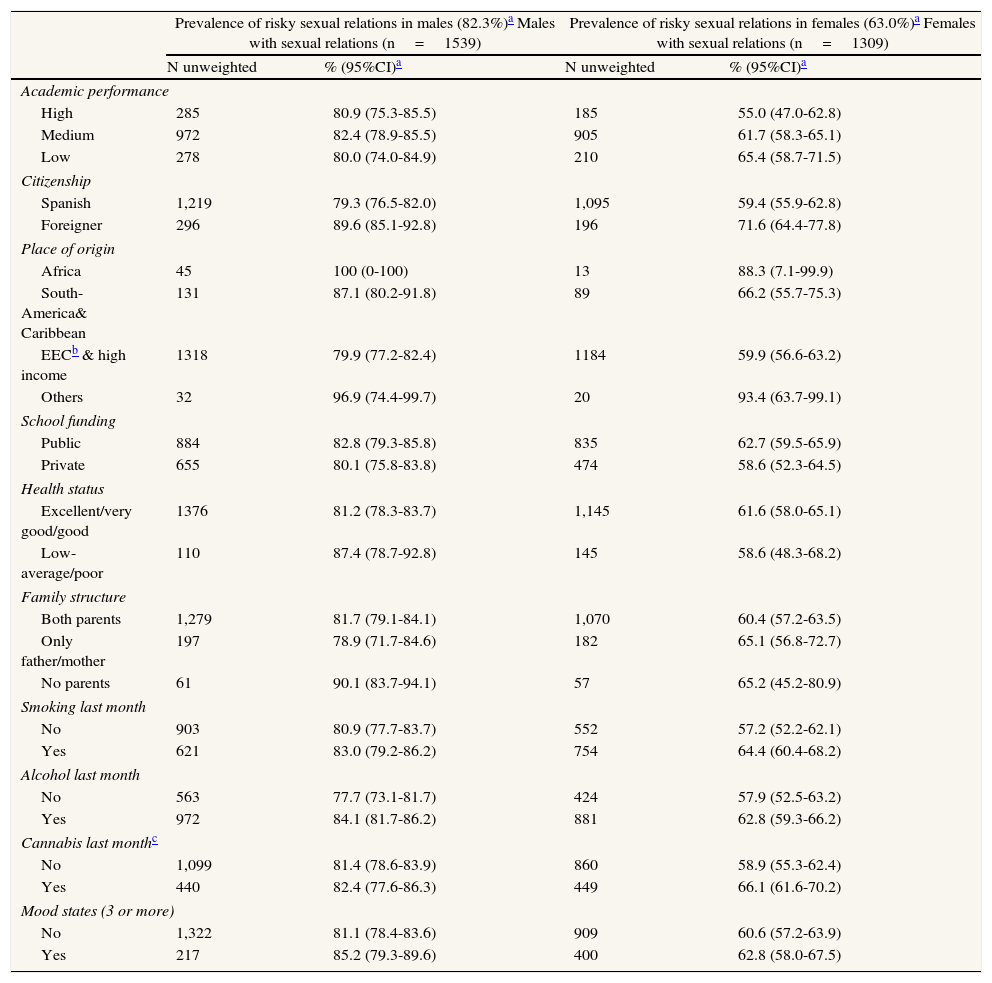

Prevalence of risky sexual relations for each category of the independent variables, stratified by gender.

| Prevalence of risky sexual relations in males (82.3%)a Males with sexual relations (n=1539) | Prevalence of risky sexual relations in females (63.0%)a Females with sexual relations (n=1309) | |||

| N unweighted | % (95%CI)a | N unweighted | % (95%CI)a | |

| Academic performance | ||||

| High | 285 | 80.9 (75.3-85.5) | 185 | 55.0 (47.0-62.8) |

| Medium | 972 | 82.4 (78.9-85.5) | 905 | 61.7 (58.3-65.1) |

| Low | 278 | 80.0 (74.0-84.9) | 210 | 65.4 (58.7-71.5) |

| Citizenship | ||||

| Spanish | 1,219 | 79.3 (76.5-82.0) | 1,095 | 59.4 (55.9-62.8) |

| Foreigner | 296 | 89.6 (85.1-92.8) | 196 | 71.6 (64.4-77.8) |

| Place of origin | ||||

| Africa | 45 | 100 (0-100) | 13 | 88.3 (7.1-99.9) |

| South-America& Caribbean | 131 | 87.1 (80.2-91.8) | 89 | 66.2 (55.7-75.3) |

| EECb & high income | 1318 | 79.9 (77.2-82.4) | 1184 | 59.9 (56.6-63.2) |

| Others | 32 | 96.9 (74.4-99.7) | 20 | 93.4 (63.7-99.1) |

| School funding | ||||

| Public | 884 | 82.8 (79.3-85.8) | 835 | 62.7 (59.5-65.9) |

| Private | 655 | 80.1 (75.8-83.8) | 474 | 58.6 (52.3-64.5) |

| Health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1376 | 81.2 (78.3-83.7) | 1,145 | 61.6 (58.0-65.1) |

| Low-average/poor | 110 | 87.4 (78.7-92.8) | 145 | 58.6 (48.3-68.2) |

| Family structure | ||||

| Both parents | 1,279 | 81.7 (79.1-84.1) | 1,070 | 60.4 (57.2-63.5) |

| Only father/mother | 197 | 78.9 (71.7-84.6) | 182 | 65.1 (56.8-72.7) |

| No parents | 61 | 90.1 (83.7-94.1) | 57 | 65.2 (45.2-80.9) |

| Smoking last month | ||||

| No | 903 | 80.9 (77.7-83.7) | 552 | 57.2 (52.2-62.1) |

| Yes | 621 | 83.0 (79.2-86.2) | 754 | 64.4 (60.4-68.2) |

| Alcohol last month | ||||

| No | 563 | 77.7 (73.1-81.7) | 424 | 57.9 (52.5-63.2) |

| Yes | 972 | 84.1 (81.7-86.2) | 881 | 62.8 (59.3-66.2) |

| Cannabis last monthc | ||||

| No | 1,099 | 81.4 (78.6-83.9) | 860 | 58.9 (55.3-62.4) |

| Yes | 440 | 82.4 (77.6-86.3) | 449 | 66.1 (61.6-70.2) |

| Mood states (3 or more) | ||||

| No | 1,322 | 81.1 (78.4-83.6) | 909 | 60.6 (57.2-63.9) |

| Yes | 217 | 85.2 (79.3-89.6) | 400 | 62.8 (58.0-67.5) |

Risky sexual relations were observed in 73.6% of sexually active students, 82.3% of males and 63% of females (P<.001). The Odds Ratio (OR) of females versus males of having a sexual risk behaviour was 0.36 (95%CI:0.29-0.43). In both genders, a high prevalence of risky practices was observed, independently of the category of prognostic variables.

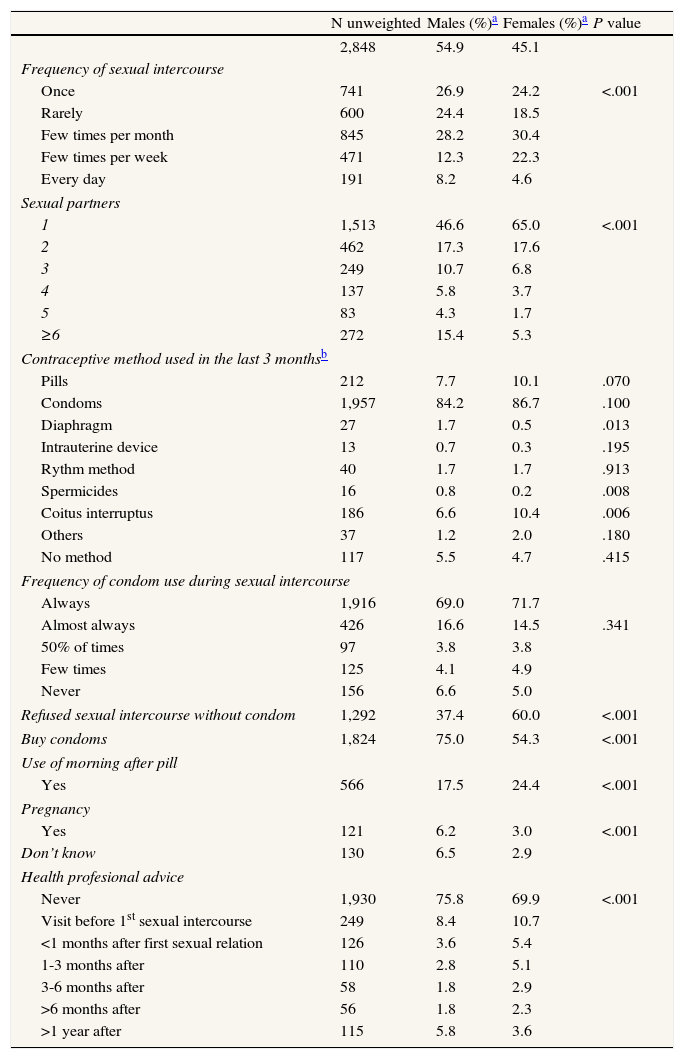

Table 3 shows the distribution of sexual behaviour characteristics according to gender; it refers only to those students that had had sexual relation at least once during their lifetime. Males had more sexual partners than females (3 or more), 36.2% versus 17.5%, and they used condoms as a contraceptive method (84.2%) less frequently than females (86.7%); however, this last difference was not statistically significant. Also, more women than men, 60.0% versus 37.4% said that they had refused to have sexual relations without protection. More females than males, 24.4% and 17.5% respectively, reported having taken the morning after pill and 6.2% of males versus 3.0% of females reported a pregnancy. More males than females reported never having turned to a health professional for advice, 75.8% versus 69.9%.

Characteristics of sexual behaviour in adolescents that have had sexual relations at least once (n=2848) according to gender.

| N unweighted | Males (%)a | Females (%)a | P value | |

| 2,848 | 54.9 | 45.1 | ||

| Frequency of sexual intercourse | ||||

| Once | 741 | 26.9 | 24.2 | <.001 |

| Rarely | 600 | 24.4 | 18.5 | |

| Few times per month | 845 | 28.2 | 30.4 | |

| Few times per week | 471 | 12.3 | 22.3 | |

| Every day | 191 | 8.2 | 4.6 | |

| Sexual partners | ||||

| 1 | 1,513 | 46.6 | 65.0 | <.001 |

| 2 | 462 | 17.3 | 17.6 | |

| 3 | 249 | 10.7 | 6.8 | |

| 4 | 137 | 5.8 | 3.7 | |

| 5 | 83 | 4.3 | 1.7 | |

| ≥6 | 272 | 15.4 | 5.3 | |

| Contraceptive method used in the last 3 monthsb | ||||

| Pills | 212 | 7.7 | 10.1 | .070 |

| Condoms | 1,957 | 84.2 | 86.7 | .100 |

| Diaphragm | 27 | 1.7 | 0.5 | .013 |

| Intrauterine device | 13 | 0.7 | 0.3 | .195 |

| Rythm method | 40 | 1.7 | 1.7 | .913 |

| Spermicides | 16 | 0.8 | 0.2 | .008 |

| Coitus interruptus | 186 | 6.6 | 10.4 | .006 |

| Others | 37 | 1.2 | 2.0 | .180 |

| No method | 117 | 5.5 | 4.7 | .415 |

| Frequency of condom use during sexual intercourse | ||||

| Always | 1,916 | 69.0 | 71.7 | |

| Almost always | 426 | 16.6 | 14.5 | .341 |

| 50% of times | 97 | 3.8 | 3.8 | |

| Few times | 125 | 4.1 | 4.9 | |

| Never | 156 | 6.6 | 5.0 | |

| Refused sexual intercourse without condom | 1,292 | 37.4 | 60.0 | <.001 |

| Buy condoms | 1,824 | 75.0 | 54.3 | <.001 |

| Use of morning after pill | ||||

| Yes | 566 | 17.5 | 24.4 | <.001 |

| Pregnancy | ||||

| Yes | 121 | 6.2 | 3.0 | <.001 |

| Don’t know | 130 | 6.5 | 2.9 | |

| Health profesional advice | ||||

| Never | 1,930 | 75.8 | 69.9 | <.001 |

| Visit before 1st sexual intercourse | 249 | 8.4 | 10.7 | |

| <1 months after first sexual relation | 126 | 3.6 | 5.4 | |

| 1-3 months after | 110 | 2.8 | 5.1 | |

| 3-6 months after | 58 | 1.8 | 2.9 | |

| >6 months after | 56 | 1.8 | 2.3 | |

| >1 year after | 115 | 5.8 | 3.6 | |

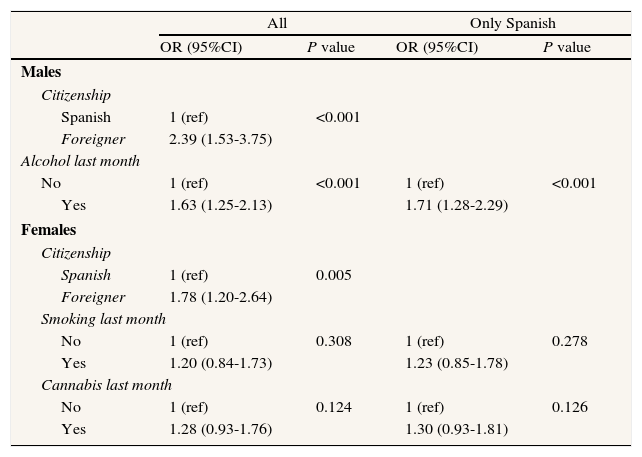

In males, the multivariate model showed that risk behaviours were higher among students with foreign origin (OR=2.39;95%CI:1.53-3.75) and among those who drank alcohol in the last month (OR=1.63;95%CI:1.25-2.13) (Table 4). When the analysis was restricted to Spanish students, alcohol consumption remained as a risk factor (OR=1.71;95%CI:1.28-2.29).

Risk factors associated with unsafe sexual behaviour in males and females. Multivariate logistic regression analysis.

| All | Only Spanish | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Males | ||||

| Citizenship | ||||

| Spanish | 1 (ref) | <0.001 | ||

| Foreigner | 2.39 (1.53-3.75) | |||

| Alcohol last month | ||||

| No | 1 (ref) | <0.001 | 1 (ref) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1.63 (1.25-2.13) | 1.71 (1.28-2.29) | ||

| Females | ||||

| Citizenship | ||||

| Spanish | 1 (ref) | 0.005 | ||

| Foreigner | 1.78 (1.20-2.64) | |||

| Smoking last month | ||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 0.308 | 1 (ref) | 0.278 |

| Yes | 1.20 (0.84-1.73) | 1.23 (0.85-1.78) | ||

| Cannabis last month | ||||

| No | 1 (ref) | 0.124 | 1 (ref) | 0.126 |

| Yes | 1.28 (0.93-1.76) | 1.30 (0.93-1.81) | ||

Adjusted for significant and confounder variables.

The multivariate model in females included foreign origin and smoking and use of cannabis during the last month. However, only the foreign origin was significantly related to the risk of having an unsafe sexual behaviour (OR=1.78;95%CI:1.20-2.64). The use of cannabis was also associated with the outcome, but this association was no longer significant when adjusted for cigarette smoking (Table 4). When the analysis was restricted to Spanish students, no variable was associated to the outcome; however, cigarette smoking and the use of cannabis were left in the model, as cigarette smoking was found to be a confounder for the use of cannabis.

DiscussionThe results of our study show that a high proportion of young students have had sexual relations and have been engaged in sexual risk behaviours. More males than females (33.6% and 27.4% respectively) from our study admitted to having had sexual relations at least once. This is a slightly higher proportion than the one found in other studies conducted in subjects approximately the same age as in our study.18,27 As found in other studies conducted in adolescents of a similar median age, our study found that of those who reported having sexual relations, more males than females reported being engaged in sexual risk behaviours.11,28

These differences in sexual relations between genders could be due to the behaviours of adolescent males. More sexually active males than females reported having multiple partners, and even though condom use is strongly associated with the reduction of several STIs,29 in our sample 15.8% of males and 13.3% of females did not use it as a contraceptive method. This percentage is even higher in other series. 30 It is important to point out that among our adolescents, a high proportion of males did not refuse to have sex without a condom. Contrarily, the female gender was significantly associated with safer sexual behaviour11 because they had fewer partners20,31 and held a more positive attitude towards the use of condoms than males.32

Aside from these sexual behaviours in adolescents, we studied other factors that could be associated with sexual risk behaviour. Some of these factors, such as age, ethnicity and family structure, have been reported in the literature as factors related to sexual relations; 33,34 however, other factors studied, such as academic performance, school funding or health status, have not been reported and could be factors associated with unsafe sexual behaviour in both genders. We also studied the consumption of addictive substances, as in the literature it has been seen that adolescents who have a history of smoking or alcohol and drug use are at a higher risk of engaging in sexual intercourse31,33-35 and these addictive substances may contribute to an increase of sexual risk behaviour among students.36

Of all the variables studied as potential factors associated with unsafe sexual relations, only foreign origin showed a higher risk for having unsafe sexual behaviour in both genders. In females no other factor was significant. An association was also found with cannabis; however, the association was not statistically significant after adjusting for smoking. It has been described in the literature that girls who have voluntary sexual relations reported multiple risk behaviours such as smoking cigarettes, smoking marijuana or alcohol consumption.35

In males, aside from foreign origin, alcohol consumption in the last month was also associated with having unsafe sex. A review of the literature found a significant positive association between drinking and risk of acquiring a STI although their causal relationship cannot be determined with certainty. The relationship did not appear to vary according to gender.37 Some of the studies in this review were carried out in adolescents. The results of these studies varied, as some reported that alcohol was a risk factor in males and others reported it to be a risk factor in females. Furthermore, the definition of alcohol consumption varied as well; some studies referred only to alcohol use, while others referred to the abuse of alcohol or alcohol dependence.

The variable foreign origin included many different countries and different cultures; however, sample sizes for ethnic groups were not large enough to allow for comparisons among them. Students of foreign origin could have had a different pattern of sexual relations from Spanish students, and for this reason we re-analysed the multivariate analysis including only Spanish people.

Even though immigrants have a well-known increased risk for STIs,38,39 there are few studies describing immigrants behaviours in Europe. In Spain and other European countries, the growing immigration movements have become very important and should be considered in school health interventions.

The study has some limitations. The information was self-reported and therefore is probably not completely accurate, either because some health risk behaviours are difficult to recall or because respondents may not want to report them. In addition, some adolescents, particularly males, may perceive the need to exaggerate their sexual involvement.

Furthermore, extensive information related to sexuality has not been collected. The current work is based on a health survey that collects information on general health related behaviours and conditions. In our study, no distinction was made between romantic and non-romantic sexual relationships, or between sequential or concurrent relationships. In addition, the survey we used did not collect information related to sexual orientation, nor did it collect information about what students considered sexual activity (vaginal, oral or anal sex, or practices that do not necessarily involve penetration).

Despite these limitations, this study, which includes 9,340 subjects representing a total population of 125,389 students, is one of the largest series in Spain that analyses adolescents’ health and provides useful information.

From our data it is possible to conclude that prevalence of sexual risk behaviour is high among adolescents in our setting, specifically in males. Aside from alcohol, there are no differences between genders with regards to socio-demographic factors and other addictive habits that increase the risk of having risky sexual relations. Therefore, a higher prevalence of risky behaviour in males may be due to factors such as attitude towards the use of condoms or attitude towards sexuality in general, as has been commented. Policymakers and social agents should put interventions into place to address sexual risk behaviours. Strategies such as providing health care and sexual education to males and females before they become sexually active should be prioritized. Schools appear to be an excellent place to intervene, and these results will be used to assess the possible future impact of the program initiated; however, in order to reduce risks, parents and the community will also have to become involved.

FundingCatalan Government Health Department, Catalonia, Spain.

Author's contributionContribute to conceiving and designing the work represented by the article or analyzing and interpreting the data: D. Puente, E. Zabaleta, B. Bolíbar, T. Rodríguez-Blanco, N. Mestre and M. Merdader. All authors have participated by drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content and by giving final approval of the version to be published.

Human subjects approval statementThe present work has been revised by the “Clinical Research Ethics Committee” of the IDIAP Jordi Gol.

Conflict of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

With thanks to the Barcelona Public Health Agency for granting permission to adapt and use some items from its previous questionnaire “Risk factors in school children”. The study was conducted with the support of the Network of Preventive Activities and Health Promotion in Primary Care [Red de Actividades Preventivas y Promoción de la Salud en Atención Primaria; redIAPP] granted by the Carlos III Health Institute [Instituto de Salud Carlos III] (RD06/0018). We would also like to thank IDIAPJGol and Mamta Advani for its support in the correction of the translation.