To describe trends in fertility in Spain before (pre-recession; 1998-2008) and during (recession period; 2009-2013) the economic crisis of 2008, taking into account women's age and regional unemployment in 2010.

MethodThe study consisted of a panel design including cross-sectional ecological data for the 17 regions of Spain. We describe fertility trends in Spain in two time periods, pre-recession (1998-2008) and recession (2009-2013). We used a cross-sectional, ecological study of Spanish-born women to calculate changes in fertility rates for each period using a linear regression model adjusted for year, period, and interaction between them.

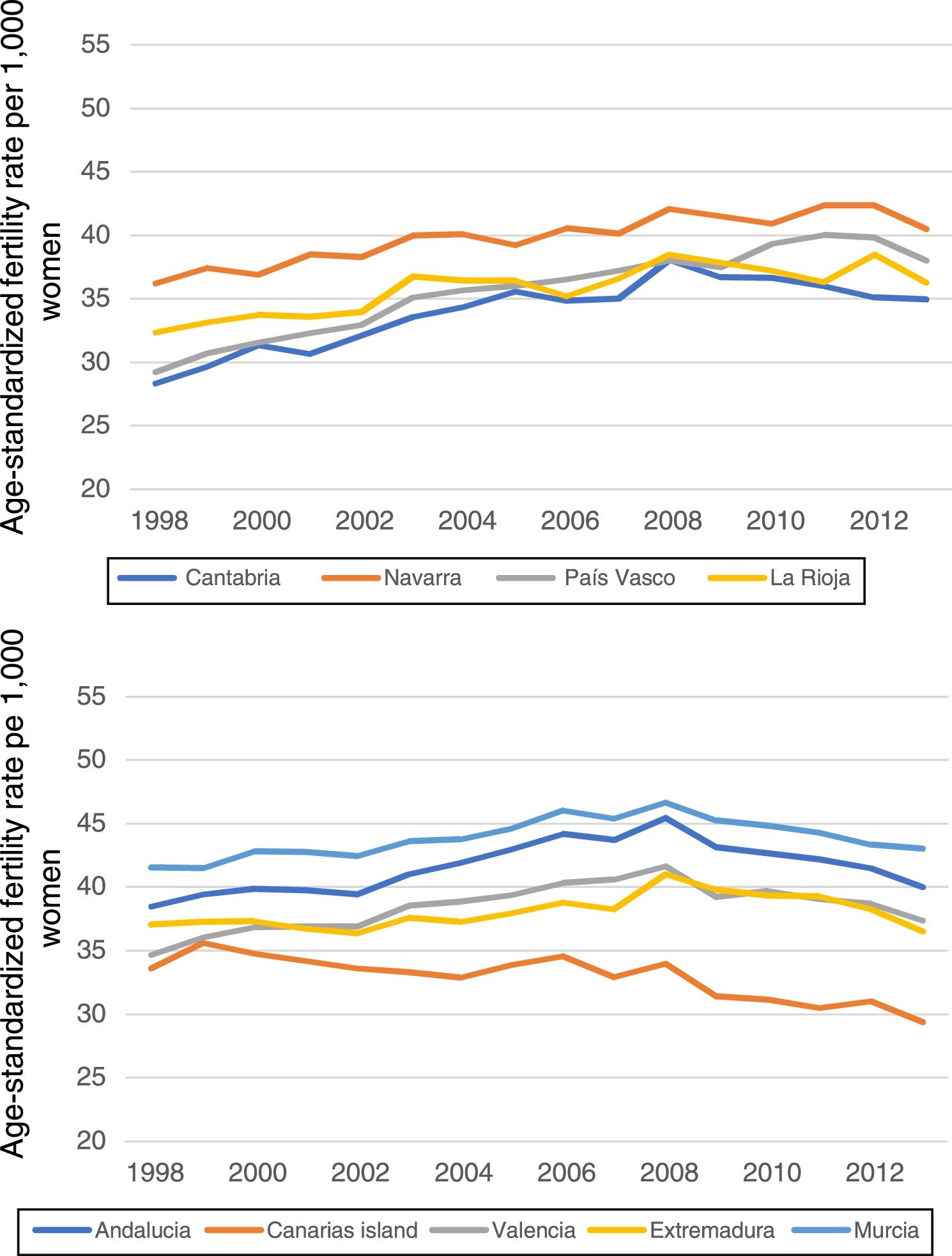

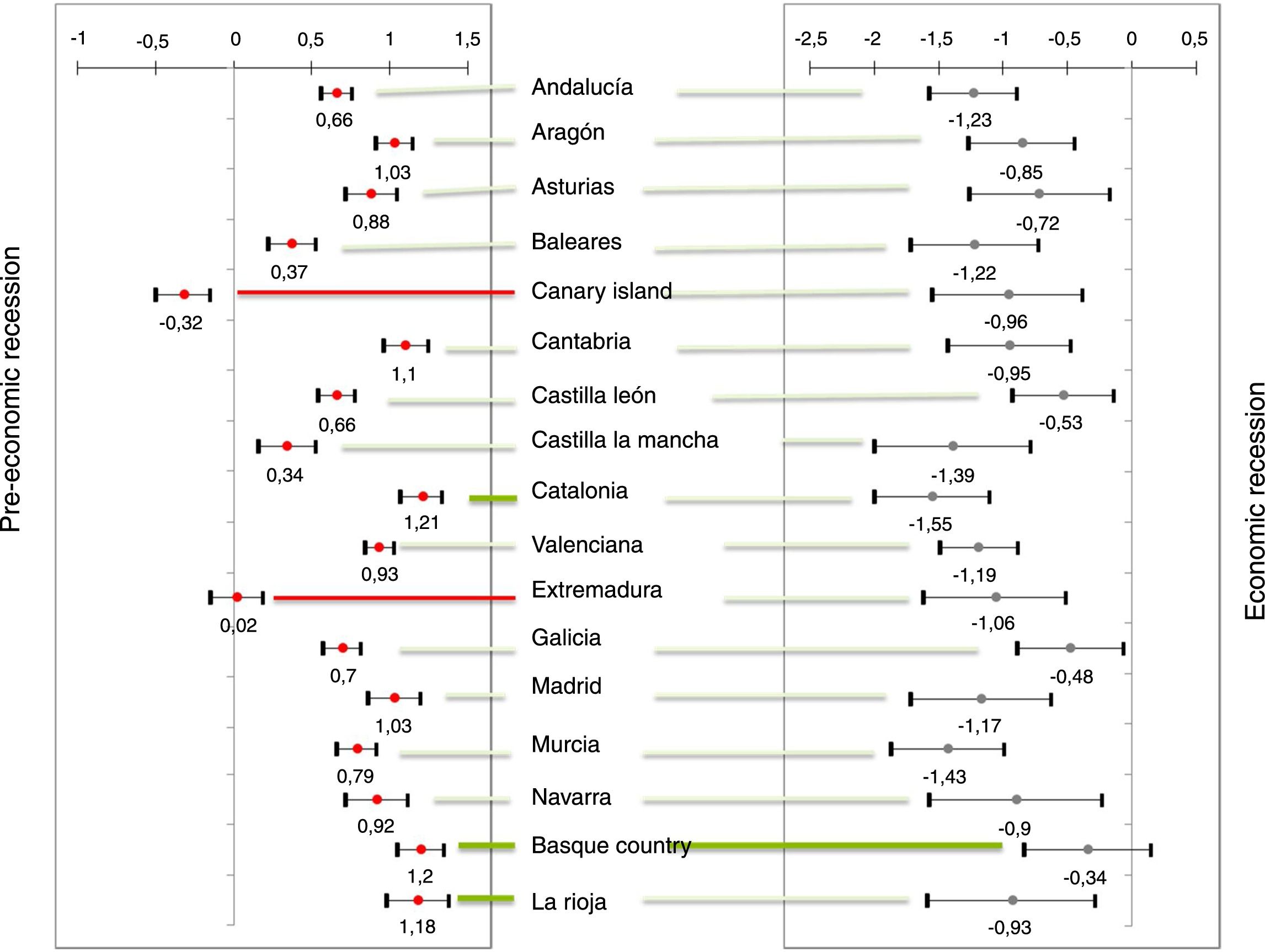

ResultsWe found that compared to the pre-recession period, the fertility rate in Spain generally decreased during the economic recession. However, in some regions, such as the Canary Islands, this decrease began before the onset of the recession, while in other regions, such as the Basque country, the fertility rate continued to grow until 2011. The effects of the recession on the fertility rate are clearly observed in women aged 30-34 years.

ConclusionsThe current economic recession has disrupted the positive trend in fertility that began at the start of this century. Since Spain already had very low fertility rates, the further decline caused by the economic recession could jeopardize the sustainability of welfare-state systems.

Describir las tendencias de la fecundidad en España en la época precrisis (1998-2008) y durante la crisis (2009-2013) económica, teniendo en cuenta la edad de las mujeres y el desempleo regional en 2010.

MétodoSe utiliza un diseño panel que incluye datos ecológicos transversales para las 17 comunidades autónomas de España. Se describen las tendencias de fecundidad en los dos periodos. Para calcular los cambios en las tasas de fecundidad se utiliza un modelo de regresión lineal ajustado por año, periodo e interacción de ellas.

ResultadosEn comparación con el periodo anterior, la tasa de fecundidad global en España disminuyó durante la crisis económica. Sin embargo, en algunas comunidades, como las Islas Canarias, esta disminución comenzó antes del inicio de la crisis, mientras que en otras, como el País Vasco, la tasa de fecundidad continuó creciendo hasta 2011. Los efectos de la crisis en la fecundidad se observan claramente en mujeres de 30 a 34 años.

ConclusionesLa crisis económica actual ha interrumpido la tendencia positiva en la fecundidad que comenzó a principios de este siglo. Dado que España ya tenía tasas de fecundidad muy bajas, el descenso causado por la crisis económica podría poner en peligro la sostenibilidad de los sistemas de bienestar social.

The decision to have children is conditioned by many factors at the level of the individual and/or couple, their social relationships and networks, and the cultural and institutional setting.1 Economic uncertainty has a profound impact on forming a family and deciding whether to have more children. Several studies link unemployment and precarious employment to delaying long-term commitments such as parenthood.2

Various theories relate economic context to fertility response, with most evidence supporting the idea that fertility responds negatively to economic downturn. Studies have generally found a pro-cyclical relationship between fertility and economic growth in high-income countries. In other words, recession, which leads to delayed childbearing, especially of the first child,3 is followed by a compensatory period in times of economic prosperity.4 In contrast, other theories suggest a counter-cyclical relationship between economic growth and fertility, albeit with less evidence. In line with this latter theory, increasing the level of employment among women would induce a decline in fertility.5

Spain is one of the European countries that has been most directly affected by the international financial crisis. The Spanish economy entered recession in the last quarter of 2008, when the GDP fell for two consecutive quarters, with negative growth of ∼1.5%. In the first quarter of 2010, unemployment increased rapidly to 20%, with over 43% of the unemployed population being under 25 years of age, being young unemployment rate the highest rate in the European Union.6 There were marked differences in unemployment across the country, ranging from 31.7% in Southern regions to 13.6% in Northern regions (Fig. 1). The Spanish government responded with a radical program of social services cuts and labor market reforms. Together with further internationalization of production and the labor market, this has led to changes in employment and working conditions towards an increase in labor flexibility and precarious work.7 The level of social cuts varied markedly between the various autonomous regions because, under the system of regional decentralization, each region has some sovereignty to implement social cuts and protection policies, including healthcare.8 Consequently, the Spanish population is suffering increased impoverishment and inequality.

Spain has had a low fertility rate since the last decades of the 20th century9 compared with other countries with a similar economic situation, fertility initially declined in upper social classes, and later in the manual social class.10

Here, we hypothesized that the economic recession would affect fertility all of Spain's autonomous regions, and that regions with a higher unemployment rate would be most affected. The aim of our study is to describe trends in fertility in Spain before (pre-recession; 1998-2008) and during (recession period; 2009-2013) the economic crisis of 2008, taking into account women's age and regional unemployment in 2010.

MethodsDesign, study population and data sourcesThis study is part of a coordinated project examining the effects of the economic crisis on health and health inequalities in Spain. The study design was based on panel data including cross-sectional ecological unemployment rates and longitudinal fertility rates for the 17 autonomous regions of Spain. The study population consisted of women 15- to 49-year-old women of Spanish nationality who were resident in Spain between 1998 and 2013. Residents of the two autonomous cities (Ceuta and Melilla) were excluded from our study. The study focused on the fertility rates during two distinct periods: 1998-2008 and 2009-2013. We analysed government vital statistics for new births, and the 2010 Economically Active Population Survey for unemployment rates. All data were obtained from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics.11

Variables and indicatorsThe main outcome (dependent variable) in our study was fertility rate, the number of live births in a given year per 1000 women aged 15-49 years. To compare fertility rates between autonomous regions during the two study periods, we calculated the standardized fertility rate (SFR) using the direct method. Standard population was calculated adding the number of women for all year in the period of study in each age group. We also calculated age-specific fertility rates as the number of births per 1000 women within specific age groups. We computed these rates for the recession and pre-recession periods. We also determined age-specific fertility rates for autonomous regions grouped into quartiles of the 2010 unemployment rate.

We considered the following stratification variables: 1) mother's age, grouped into seven intervals of five years (15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-44, and 45-49 years); 2) autonomous region, grouping the 17 regions according to quartiles of the 2010 unemployment rate (for statistical interest given the sparsity of the data); 3) year, from 1998 to 2013; and 4) time period, either pre-recession (1998 to 2008) or recession (2009 to 2013).

Statistical analysisFirst, we described the SFR trends in 15 to 49-year-old women separately for each autonomous region, and for all years between 1998 and 2013. Second, we obtained age-specific fertility rates, and fertility rates for autonomous regions grouped by unemployment quartile. To explain the annual change in fertility rate, we adjusted fixed-effects linear regression models for balanced panel data (see online Appendix). Since our observations depended on the autonomous region, we clustered the standard errors of the coefficient estimates for possible dependence in the residuals. We include the following explanatory variables in the models: year, period (pre-recession versus recession), and the interaction between year and period. We used the coefficients of the interaction term, their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and the p-values to estimate the annual change in fertility rate. We fit three different models: 1) fertility rate in women aged 15 to 49; 2) age group-stratified fertility rate in autonomous regions grouped by unemployment quartiles; and 3) fertility rate in each autonomous region.

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11.

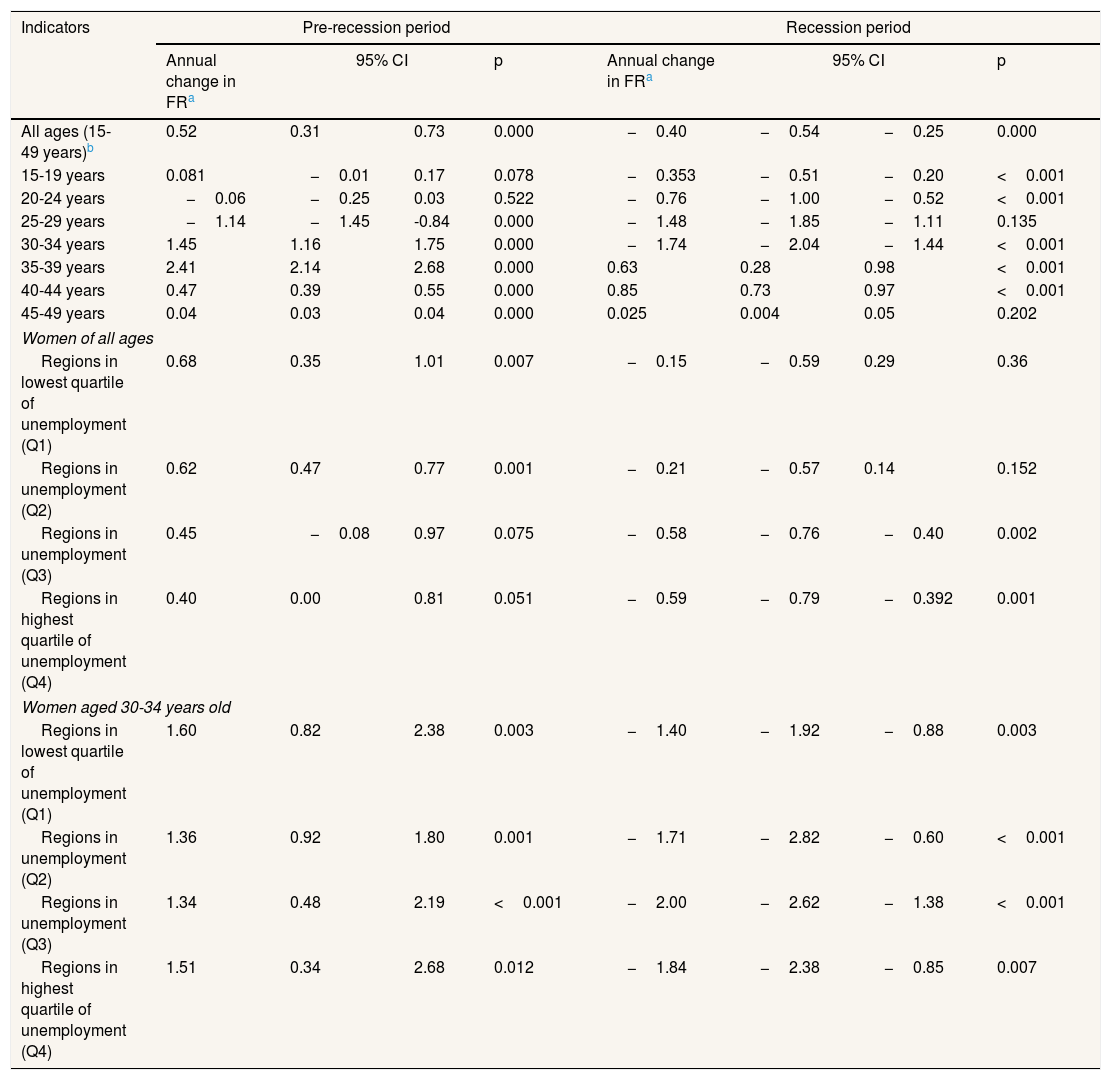

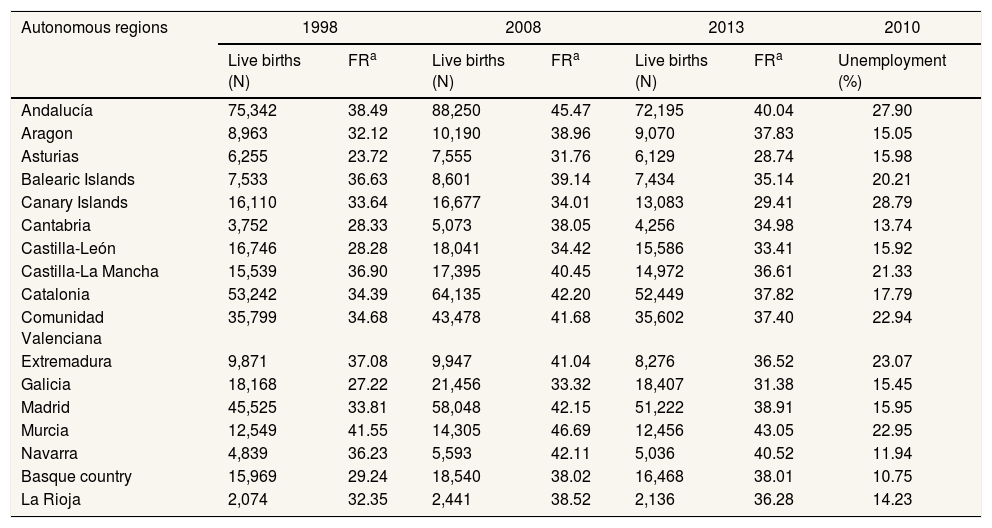

ResultsThe average number of births per year in Spain between 1998 and 2013 was 367,593. In almost all the autonomous regions of Spain, SFR increased until 2008 and decreased thereafter until 2013. Similarly, the fertility rate in women aged 15-49 years significantly increased before the economic recession but decreased significantly during the economic recession (pre-recession 0.52; 95% CI: 0.31-0.73; recession 0.40; 95% CI: -0.54 -0.25).

With respect to age, young women showed a significant decrease in fertility during the recession period. Similarly, middle aged women (30 to 34 and 35 to 39 year old), who have the highest fertility rate) showed a significant increase in fertility before the recession but an opposite effect during the recession period– in the first group is positive and in the other negative (Table 1). The fertility rate of women in the older age groups increased during both periods.

Change in fertility rate in Spain during the pre-recession (1998 to 2008) and recession (2009-2013) periods as a function of age group and autonomous regions grouped by quartile of unemployment.

| Indicators | Pre-recession period | Recession period | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual change in FRa | 95% CI | p | Annual change in FRa | 95% CI | p | |||

| All ages (15-49 years)b | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.73 | 0.000 | −0.40 | −0.54 | −0.25 | 0.000 |

| 15-19 years | 0.081 | −0.01 | 0.17 | 0.078 | −0.353 | −0.51 | −0.20 | <0.001 |

| 20-24 years | −0.06 | −0.25 | 0.03 | 0.522 | −0.76 | −1.00 | −0.52 | <0.001 |

| 25-29 years | −1.14 | −1.45 | -0.84 | 0.000 | −1.48 | −1.85 | −1.11 | 0.135 |

| 30-34 years | 1.45 | 1.16 | 1.75 | 0.000 | −1.74 | −2.04 | −1.44 | <0.001 |

| 35-39 years | 2.41 | 2.14 | 2.68 | 0.000 | 0.63 | 0.28 | 0.98 | <0.001 |

| 40-44 years | 0.47 | 0.39 | 0.55 | 0.000 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 0.97 | <0.001 |

| 45-49 years | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.000 | 0.025 | 0.004 | 0.05 | 0.202 |

| Women of all ages | ||||||||

| Regions in lowest quartile of unemployment (Q1) | 0.68 | 0.35 | 1.01 | 0.007 | −0.15 | −0.59 | 0.29 | 0.36 |

| Regions in unemployment (Q2) | 0.62 | 0.47 | 0.77 | 0.001 | −0.21 | −0.57 | 0.14 | 0.152 |

| Regions in unemployment (Q3) | 0.45 | −0.08 | 0.97 | 0.075 | −0.58 | −0.76 | −0.40 | 0.002 |

| Regions in highest quartile of unemployment (Q4) | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.81 | 0.051 | −0.59 | −0.79 | −0.392 | 0.001 |

| Women aged 30-34 years old | ||||||||

| Regions in lowest quartile of unemployment (Q1) | 1.60 | 0.82 | 2.38 | 0.003 | −1.40 | −1.92 | −0.88 | 0.003 |

| Regions in unemployment (Q2) | 1.36 | 0.92 | 1.80 | 0.001 | −1.71 | −2.82 | −0.60 | <0.001 |

| Regions in unemployment (Q3) | 1.34 | 0.48 | 2.19 | <0.001 | −2.00 | −2.62 | −1.38 | <0.001 |

| Regions in highest quartile of unemployment (Q4) | 1.51 | 0.34 | 2.68 | 0.012 | −1.84 | −2.38 | −0.85 | 0.007 |

95% CI=95% confidence interval; FR: fertility rate (number of births per 1000 women).

In some autonomous regions, mainly the northern regions, where unemployment is generally lower (Fig. 1), global SFR continued to increase increased until the end of the pre-recession period. The global SFR varied markedly between autonomous regions. In 2008, for example, the SFR in Murcia (in the south) was 46.69, while that in Asturias (in the north) was 31.76. This variability in SFR between regions was slightly greater at the start of the study period (1998) than in 2008 or 2013 (Table 2).

Age-standardized fertility rate in women aged 15 to 49 in 1998, 2008, and 2013, and the 2010 unemployment rate in Spain's autonomous regions.

| Autonomous regions | 1998 | 2008 | 2013 | 2010 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Live births (N) | FRa | Live births (N) | FRa | Live births (N) | FRa | Unemployment (%) | |

| Andalucía | 75,342 | 38.49 | 88,250 | 45.47 | 72,195 | 40.04 | 27.90 |

| Aragon | 8,963 | 32.12 | 10,190 | 38.96 | 9,070 | 37.83 | 15.05 |

| Asturias | 6,255 | 23.72 | 7,555 | 31.76 | 6,129 | 28.74 | 15.98 |

| Balearic Islands | 7,533 | 36.63 | 8,601 | 39.14 | 7,434 | 35.14 | 20.21 |

| Canary Islands | 16,110 | 33.64 | 16,677 | 34.01 | 13,083 | 29.41 | 28.79 |

| Cantabria | 3,752 | 28.33 | 5,073 | 38.05 | 4,256 | 34.98 | 13.74 |

| Castilla-León | 16,746 | 28.28 | 18,041 | 34.42 | 15,586 | 33.41 | 15.92 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 15,539 | 36.90 | 17,395 | 40.45 | 14,972 | 36.61 | 21.33 |

| Catalonia | 53,242 | 34.39 | 64,135 | 42.20 | 52,449 | 37.82 | 17.79 |

| Comunidad Valenciana | 35,799 | 34.68 | 43,478 | 41.68 | 35,602 | 37.40 | 22.94 |

| Extremadura | 9,871 | 37.08 | 9,947 | 41.04 | 8,276 | 36.52 | 23.07 |

| Galicia | 18,168 | 27.22 | 21,456 | 33.32 | 18,407 | 31.38 | 15.45 |

| Madrid | 45,525 | 33.81 | 58,048 | 42.15 | 51,222 | 38.91 | 15.95 |

| Murcia | 12,549 | 41.55 | 14,305 | 46.69 | 12,456 | 43.05 | 22.95 |

| Navarra | 4,839 | 36.23 | 5,593 | 42.11 | 5,036 | 40.52 | 11.94 |

| Basque country | 15,969 | 29.24 | 18,540 | 38.02 | 16,468 | 38.01 | 10.75 |

| La Rioja | 2,074 | 32.35 | 2,441 | 38.52 | 2,136 | 36.28 | 14.23 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; FR: fertility rate (number of births per 1000 women).

Coefficient of variation for 1998=14%; for 2008=11%; for 2013=11%.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of global fertility rates in autonomous regions grouped by unemployment quartile. Except for the Basque country, the global fertility rates of the autonomous regions in the first (lowest) unemployment quartile began to decrease in 2008 with the onset of the economic recession. In the Basque Country, the rate continued to increase until 2011, after which it decreased only slightly. In the fourth (highest) unemployment quartile the decrease in global fertility rate also generally started in 2008. In contrast, the rate in the Canary Islands began to decrease even before the recession. Notably, the regions in the fourth unemployment quartile showed the highest global SFR (Fig. 2).

Trends in global fertility rates in women aged 15-49 years old in autonomous regions grouped by unemployment quartiles, Spain 1998-2013 (population of 11,016,410 women aged 15-49).

Quartile 1 - Autonomous regions with the lowest unemployment levels

Quartile 4 - Autonomous regions with the highest unemployment levels.

All four unemployment quartiles showed an increase in the global fertility rate for the pre-recession period, but a decrease during the recession, with the largest decrease in regions in the fourth quartile (Table 1). The pattern of fertility rates among women aged 30 to 34 years (the age group with the highest fertility) is consistent with that for all ages, albeit with less variability.

The linear regression analyses for each autonomous region show a general annual increase in fertility rates during the pre-recession period, except for the Canary Islands, which has experienced declining fertility since 1998, and Extremadura. Interestingly, both of these regions are in the highest quartile of unemployment. The highest annual increase in fertility rates during the pre-recession period were observed in the Basque country, La Rioja and Catalonia (Fig. 3). In contrast, we observe a decrease in the annual fertility rate in all regions during the recession, although this trend was not statistically significant for the Basque Country, a region that has been growing more than the rest (Fig. 3).

DiscussionThis study shows that, compared to the pre-recession period, the fertility rate in Spain generally decreased during the economic recession. However, in some regions, such as the Canary Islands (high unemployment rate region), this decrease began before the onset of the recession, while in other regions, such as the Basque country (low unemployment rate region), the fertility rate continued to grow until 2011. The effects of the recession on the fertility rate are clearly observed in women aged 30-34 years.

Our results are similar to those obtained in other studies, where fertility rates in other European countries stopped increasing after 2008.12 Moreover, as in Spain, recession-related unemployment has been linked to reduced fertility rates in other European countries.13 Spain is known to have unstable job entry patterns, and the recession has further exacerbated the problems young Spanish people face.14

In previous economic crises, fertility rates are known to have decreased mainly because of labor uncertainty, which hinders planning. A poor economic situation can postpone starting a family through generating higher unemployment, lower employment stability, greater uncertainty about the future, changes in the housing market, prolonged enrolment in education, and delayed union formation.15

These adverse economic conditions and high levels of unemployment significantly reduce fertility rates, especially in women in the manual social class.16 Furthermore, the recovery of fertility rates is associated with access to labor markets and/or entry into cohabiting unions.17 The impact of uncertainty, however, is mediated by regional factors, such as how much welfare protection young adults receive,18 and also by individual factors, including the mother's level of education or women income.19 Family and other welfare policies also have an effect on fertility rates.

Since recovering democracy in 1977, Spain has progressively evolved into a low birth-rate country, possibly because of greater access to education for women, a massive incorporation of women into the labor market, and a gradual increase in the use of contraception. This new structural situation for women contrasts with the “traditional family policy model” defined by Korpi.20 In this traditional model, the gender division of labor and preservation of traditional family patterns is encouraged by high levels of family support and inadequate approval for female participation in the labor force. Spain continues to have a traditional gender division of labor, with men acting as the breadwinners and women as the main caregivers and secondary earners. Scarce provision of childcare and other services compel women to take care of their own children, especially during the pre-school years, as the public schooling system for children under 3 has insufficient coverage. Thus, Spanish women tend to have fewer children than they desire. The difficulty in establishing an independent household and in combining motherhood and employment appear to be responsible for the delay in having the first child and often even the second.21

In Scandinavian European countries, governments generally spend more on family policies than in other parts of Europe, notably Spain. It has also been shown that fertility trends are influenced by family income as well as by the direct and indirect costs of having children.22 These factors could also influence the low fertility rates seen in Spain.23 However, this argument might only be valid for Spanish women, as the fertility pattern for women of foreign nationality residing in Spain differs, in that it is mainly characterized by higher fertility rates and lower income.24

With the onset of the economic recession, the Spanish government implemented a social policy aimed at boosting Spain's population. Although it had no effect on fertility, between 2007 and 2010 the so-called’baby chequé was a direct payment given to the mothers of newborn babies. Some of the initiatives in family policies coincided with increasing concerns in European countries about low fertility and the sustainability of Welfare-state systems. These concerns revived debates about family policies as a remedy against fertility decline and its presumed consequences. Further findings suggest that policies directed at employment and income maintenance, gender equality, and care support may be more conducive to fertility increases in Europe than explicitly fertility-focused family policies.25

At the same time, however, Spain was one of the European Union countries that adopted austerity policies with large cuts in public spending and public sector reforms. It has recently been pointed out that, compared to European Union countries who opted for fiscal stimulus, these austerity measures adversely affected the economic recovery of countries who applied them.26

Moreover, the policies implemented in response to the economic crisis have been highly gender-biased. Austerity measures undermined important employment and social protection programs, with the effect of prolonging gender inequality. Consequently, there has been an ideological retreat favoring regression to traditional, backward-looking gender roles.27 Together with declining family incomes, this has caused the recession to mainly affect women (e.g., eating more frequently at home and removing children from expensive nurseries).

Furthermore, the regions of Spain that experience higher unemployment tend to show a greater decline in fertility (not statistically significant) while fertility rates in Spain are still higher in the recession period in the regions with lowest unemployment. With regards to these lower fertility rates, the regional differences in gender policy cuts can be attributed not only to differences in political ideology but also in regional wealth.28 Also, in the specific case of the current recession, its impact on European countries as a whole has been described, highlighting its greater effect on Spain, as well as the role that different policies can play in mitigating or increasing this impact.29

One of the limitations of this study is that we only used unemployment to measure the effects of the economic crisis. There are, however, other consequences of economic recession such as cuts in welfare policies, which we have not considered. Nevertheless, global unemployment is a good indicator of the impact of economic crisis on society, a common indicator of the labor market situation, and has been used as such in many of the studies referenced above. We used unemployment levels from 2010 as a fixed effect in our analysis of longitudinal fertility rates. While the unemployment rate in 2010 was higher than in other years, its distribution among the autonomous regions shows the same pattern consistently over time.

Another limitation of our study is that we did not explore the relationship between fertility and labor market. Furthermore, we did not examine the effect of youth unemployment on fertility rate. In this sense, there is a notable positive relationship between fertility and some productive sectors, such as the public sector, which is mainly composed of women. It would also be interesting to examine how fertility is affected by eliminating civil servant positions.30 Finally, we did not evaluate whether the recession affects fertility patterns among immigrants differently to those among Spanish-born women.

Other indicators could also be used as the Synthetic Fertility Index. It expresses the number of children that a hypothetical woman would have at the end of her fertile life, if, during the same period, her behavior corresponded, at each age, with that which reflects the series of specific fertility rates by age. This indicator is not influenced by the irregularities of women of childbearing age. One of the most important criticisms of the use of the Synthetic Fertility Index is that its calculation is influenced by the delay of having children as occurs in Spain. It use would need important corrections of intensity, calendar and variance effects.

As strengths, it is worth noting the significant number of years used in the pre-crisis period from 1998 to 2008. Also, since it is the official source of the country's birth data, the data used are of good quality and exhaustive. Another strength is the use of standardization to calculate the fertility which is not usual in demographic context. Standardized fertility rate allows us to compare fertility between regions of the country along the study years.

ConclusionThe current economic recession has disrupted the positive trend in fertility that began at the start of this century. Since Spain already had very low fertility rates, the further decline caused by the economic recession jeopardizes the future of the country's welfare system.

There is evidence supporting the idea that fertility responds negatively to economic downturn in a pro-cyclical although other theories suggest a counter-cyclical relationship between economic growth and fertility, albeit with less evidence.

What does this study add to the literature?The current economic recession has disrupted the positive trend in fertility that began at the start of this century. The regions of Spain that experience higher unemployment tend to show a greater decline in fertility. Since Spain already had very low fertility rates, the further decline caused by the economic recession jeopardizes the future of the country's welfare system.

Mercedes Carrasco Portiño.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsV. Puig-Barrachina, M. Rodríguez-Sanz and G. Perez have made substantial contributions to conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data. V. Puig-Barrachina, G. Perez and M.A. Luque have been involved in drafting the manuscript. M.F. Domínguez-Berjón, U. Martín and M. Ruiz have made substantial contributions, to the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data. All authors revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and given final approval of the version to be published.

AcknowledgmentsWe thank Dr. Gavin Lucas and colleagues at ThePaperMill for critical reading and editing of this paper.

FundingThis study was partially supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (cofinanced by the European Regional Development Fund) in the Acción estratégica en salud 2013-2016 (PI13/02292), and the social determinants of health program of the CIBER of Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP).

Conflicts of interestNone.