The 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health

Más datosHealth problems are complex problems the resultant of various environmental problems that are natural and man-made, socio-cultural, behavior, population, and genetics.

MethodThis research is a qualitative type with an ethnographic approach which is also supported by a phenomenological approach.

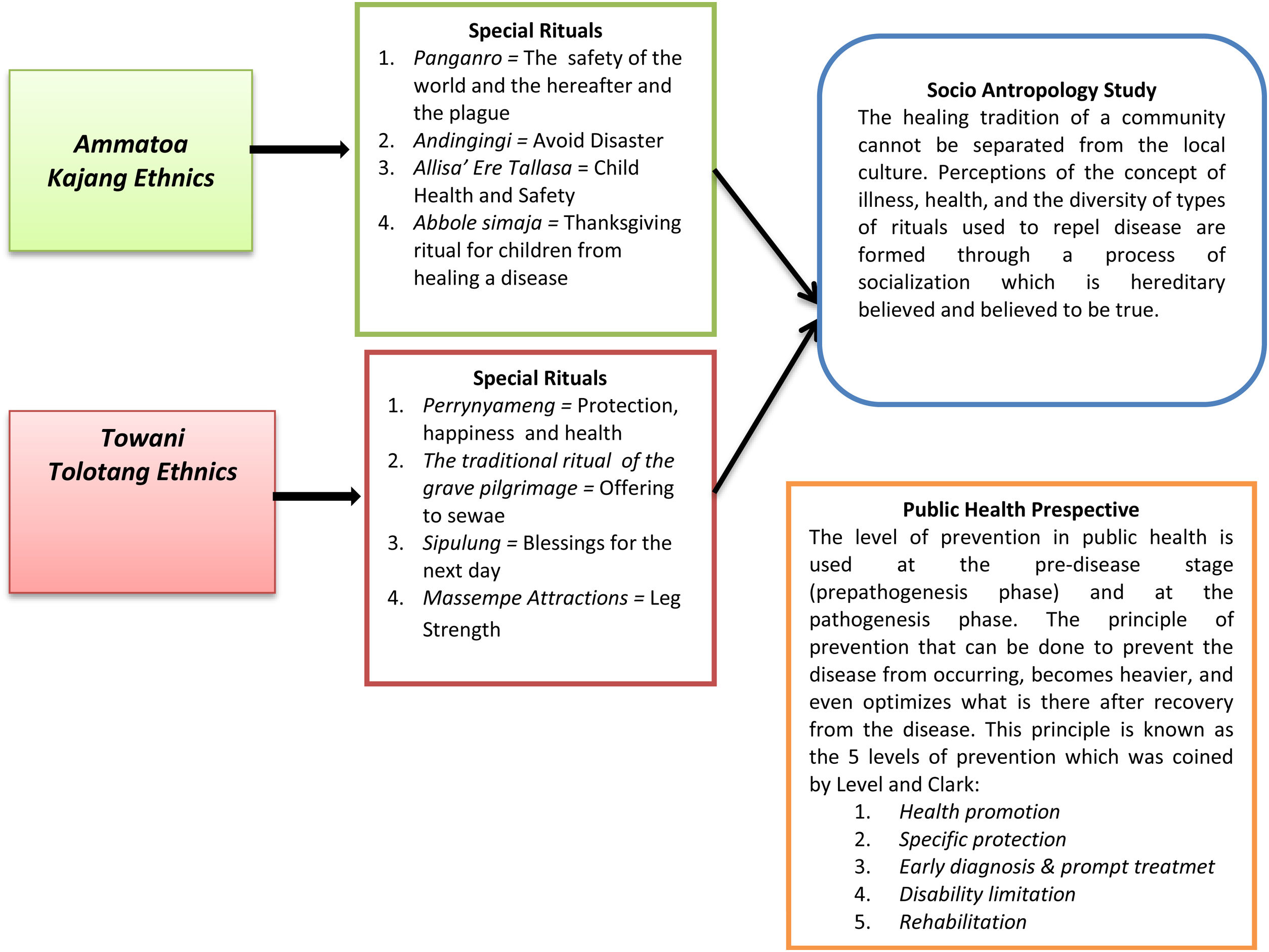

ResultsIn the Ammatoa Kajang tribe, there are 4 special rituals related to health, namely Panganro (safety of the world and the hereafter and disease outbreaks), Andingingi (avoiding disasters), Allisa’EreTallasa (health and safety of children), and Abbolesimaja (healing of diseases in children). The Towani Tolotang tribe has a Perrynyameng ritual, Sipulung ritual which aims to ask for protection, happiness, and health. Massempe attractions to test leg strength in children.

ConclusionsPerceptions of the concept of illness, health, and the diversity of types of rituals used to repel disease are formed through a process of socialization which is hereditary believed and believed to be true.

Indonesia is famous for its various ethnic groups and cultures, in South Sulawesi Province there are four major tribes, namely Toraja, Mandar, Makassar, and Bugis. The Toraja tribe is dominated by the Christian community by adhering to the Aluk Todolo belief. Meanwhile, the majority of the Makassar and Bugis tribes are Muslim and among them are patuntung (Kajang) and Tolotong (Sidrap).1 Belief and religious factors will certainly have an impact on thinking and a series of different patterns of behavior. This will also affect the individuals and community in maintaining their health. The culture of health behavior that exists in society is diverse and is inherent in social life. So that the effort that must be made to change this culture is to study their culture and create an innovative culture in accordance with patterns, norms, and objects made by humans.

The behavior that develops in society is the contribution of previous community behavior which is passed onto future generations, such as rituals, magical, religious interests as symbols or status symbols of the opening work between places is called modernization, fulfilling individual and group needs including ritual, human treatment of the environment, processing of the natural environment to achieve goals, livelihoods and beliefs, objects that are made and used as life defense against the environment, creation of tools to maintain health, and producing protecting oneself.2 Culture and behavior are not only obstacles and challenges to health, but can also be supporting factors, Research conducted shows that the traditional culture of people is a culture that is passed down from generation to generation.3

Based on this phenomenon, the researchers wanted to conduct an in-depth study related to rituals and health in the Towani Tolotang and Amma Toa Kajang Tribe. The Towani Tolotang community is interesting to study because it adheres to a social system from the concept of religion that they understand which makes religion the basis of the pattern of social life in society and as a measure of good and bad in social life. Regardless of the dynamics of this community, which are always wracked with cynicism and are considered conservative, they persist with their understanding, one of which is the paradigm of healthy living. They still maintain beliefs about how someone can maintain health, take medication, and prevent disease. Referring to the cultural essence of the Towani Tolotang Tribe and the Amma Toa Kajang Tribe, cultural values are an integral part of their existence as an effort to create a healthy life and are part of a culture that is found universally. From the cultural structure that is owned, public health can be traced, namely through special rituals that developed in the Towani Tolotang Tribe and the Amma Toa Kajang Tribe.

MethodThis research is a type of qualitative research with an ethnographic approach which is also supported by a phenomenological approach, which explores and studies information in a structured and in-depth manner about special rituals carried out by the Tolotang and Ammatoa tribes related to public health.

ResultsBasically, the Amma Toa Kajang area has many rituals as explained by Ammatoa, namely Injo Panganro (rituals for lino and ahere safety and disease outbreaks), Andingingi (rituals to avoid disasters), Allisa’Ere Tallasa (rituals for health and child safety), Abbole simaja (thanksgiving ritual for children from healing a disease). In addition, there are certain prohibitions that must be followed by all Amma Toa Kajang customary communities.

Information obtained from the Amma (Ammatoa/leader) in AmmatoaThe panganro, andingingi, allisa ere tallasa, and the abbole simaja event. Because our descendants didn’t wear sandals, didn’t wear trousers, didn’t wear shirts. But now only those who live in the village are defensive, the areas outside are modern too, but indeed the descendants of the past don’t wear sandals (Inf. 005, Amma, male 68 years).

The Towani Tolotang Sidrap community is famous for its perrynyameng ritual which is held on Mount Lowa every January with the aim of getting protection, happiness and health. There is no special characteristic that distinguishes this community from the surrounding community, which is predominantly Bugis, in fact they also maintain their identity as Bugis. However, they have different beliefs from other residents who are predominantly Muslim. Overall, the Tolotang belief has a strong influence, or even dominates the way of life of its adherents, including its culture and social system.

Information obtained from the Uwa (Uwatta/leader) in TolotangThe traditional ritual here, usually called perrynyameng on Mount Lowa, is usually done in January, to get protection, happiness and health from Dewata Seawae (Inf. 015, Uw, male 61 years).

Another explanation from the informants was that they also had the habit of not wearing sandals when performing traditional rituals, and had a habit of bathing at dawn.

This is a hereditary habit here. At dawn – at dawn we take a shower, wash our new bodies into the fields. Here there is also a ritual for us to go to the mountain on foot without wearing sandals, maybe that's what makes us healthy (Inf. 012, Dha, female 51 years).

DiscussionThe people of the Amma Toa Kajang tribe have a ritual of the Pa’nganro ceremony, which is a ceremony to say prayers to be given safety and to avoid disasters such as long droughts and disease outbreaks. In addition, this ceremony is also usually performed to pray for rain. Meanwhile, the Allisa’Ere Tallasa ceremony, which is the ceremony when a child first sets his foot on the ground. This ceremony is carried out to ask for blessings so that the steps of their children in the future become useful steps for the family and society, this ritual is believed to be the health and safety of children. The Towani Tolotang people have a ritual known as Perrynyameng which aims to ask for protection, happiness, and health from the patotoe/ancestors. The traditional ritual of the grave pilgrimage for offerings to the lease to avoid accidents including certain diseases, the Sipulung event for blessings in the next day, and Massempe attractions to test the strength of the legs in children (Fig. 1).

Ethnicity, cultural differences and social groups greatly influence disease and health.4 The traditional medicine system is not just a medical and economic phenomenon, but more broadly as a socio-cultural phenomenon. Ordinary people or experts tend to view traditional medicine from an economic and medical perspective only, rarely or even there has been no more specific research through a social and cultural perspective by engaging directly in people's lives, for example by measuring the extent to which traditional medicine and medicines are seen as health care needs by the community.5

Beliefs and practices regarding disease, which are the result of indigenous cultural development and which do not explicitly originate from the framework of modern medicine, are a direct sequence of the anthropologists’conceptual framework of Rivers’ non-western medical systems (medicine, magic, and religion).6 Religious beliefs and practices have major consequences for personal and public health. From dietary restrictions and substance use and avoidance to family planning, organ donation, and the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases, religious customs affect the quality of life of millions of people around the world.7–9

Anthropological and evolutionary-science literature offers a psychological account of the social functions of ritual for group behavior. Solving the adaptive problems associated with group living requires psychological mechanisms for identifying group members, ensuring their commitment to the group, facilitating cooperation with coalitions, and maintaining group cohesion. The intersection of these lines of inquiry yields new avenues for theory and research on the evolution and ontogeny of social group cognition.10

The study of rituals has a rich history in the anthropological, sociological, and psychological literature, with a particular focus on the interpersonal effects of rituals. Previous research has identified both functional and dysfunctional consequences of group rituals.11–13 Socio Anthropology has views on the importance of a cultural approach. Culture itself is passed down from one generation to the next by using symbols, language, art, and rituals that are carried out in the form of everyday life. On the other hand, cultural background has an important influence on various aspects of human life (beliefs, behavior, perceptions, emotions, language, religion, rituals, family structure, diet, clothing, attitudes toward illness, etc.). Furthermore, these things will certainly affect the health status of the community and the pattern of desperate health services in the community.14,15

Health anthropology helps to study the socio-cultural of all societies associated with illness and health as the center of culture, including diseases related to belief (misfortunes).16,17 There is an intimate and inexorable relationship between disease, drugs, and culture. Disease theory including etiology, diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and improvement or treatment are all part of the culture. Ethnomedicine initially studied medicine in primitive societies or those that are still considered traditional, although in further development this stereotype should be avoided because traditional medicine is not always backward or wrong.18–20

ConclusionsPerceptions of the concept of illness, health, and the diversity of types of rituals used to repel disease are formed through a process of socialization which is hereditary believed and believed to be true. A health program is needed with community involvement in accordance with customs without reducing the essence of public health in maintaining, enhancing, and protecting the health and the environment based on local cultural institutions. The focus of the program is dealing with bad habits that cause health problems and handling participation.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 1st International Conference on Safety and Public Health (ICOS-PH 2020). Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.