In this paper, we describe our experience of using the Putting Women First protocol in the design and implementation of a cross-sectional study on violence against women (VAW) among 1607 immigrant women from Morocco, Ecuador and Romania living in Spain in 2011. The Putting Women First protocol is an ethical guideline for VAW research, which includes recommendations to ensure the safety of the women involved in studies on this subject. The response rate in this study was 59.3%. The prevalence of VAW cases last year was 11.7%, of which 15.6% corresponded to Ecuadorian women, 10.9% to Moroccan women and 8.6% to Romanian women. We consider that the most important goal for future research is the use of VAW scales validated in different languages, which would help to overcome the language barriers encountered in this study.

En este trabajo se describe la experiencia de la aplicación del protocolo Putting Women First en el diseño y la realización de un estudio transversal sobre violencia contra las mujeres en 1607 mujeres inmigrantes procedentes de Marruecos, Ecuador y Rumanía residentes en España (2011). Este protocolo es un código ético para la investigación sobre la violencia contra las mujeres que incluye recomendaciones para preservar la seguridad de quienes participan en estudios sobre el tema. Se obtuvo una tasa de respuesta del 59,3%. La prevalencia de casos declarados de violencia contra las mujeres en el último año fue del 11,7%: el 15,6% en las mujeres ecuatorianas, el 10,9% en las marroquís y el 8,6% en las rumanas. El reto que consideramos más relevante para futuras investigaciones es la utilización de escalas sobre violencia contra las mujeres validadas para diferentes idiomas, con el objeto de romper las barreras lingüísticas encontradas en este caso.

The Putting Women First protocol is a well-known safety and ethical guideline for research on violence against women (VAW).1 It was drawn up in 2001 by a research team led by Claudia García-Moreno after carrying out a WHO multi-country study on the prevalence, risk factors and health consequences of VAW.2

The protocol contains recommendations concerning the ethical and safety factors to be taken into consideration when conducting VAW research and the methodological approaches required by this type of study.2

The aim of this paper is to describe the use of the Putting Women First protocol in a cross-sectional study carried out on the most numerous groups of immigrant women in Spain: Moroccan, Romanian and Ecuadorian women living in the provinces of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia (2011–2012). The differences between them as regards their sociodemographic and migratory process characteristics, combined with the paucity of VAW studies on Ecuadorian,3 Rumanian4 and Moroccan women meant that this study provided the opportunity to assess the strengths and limitations to be taken into account in future research.

The safety factor as a priority in violence against women researchBattered women could be at further risk if their violent partners were to discover that they had participated in a study on VAW. Therefore, careful planning during the study design stage as regards where and how to conduct the interview is of paramount importance. Access to immigrant women may be further complicated due to linguistic barriers and their employment and legal situation. Consequently, when planning data collection strategies, it is also necessary to identify a list of suitable places to contact the target population.5

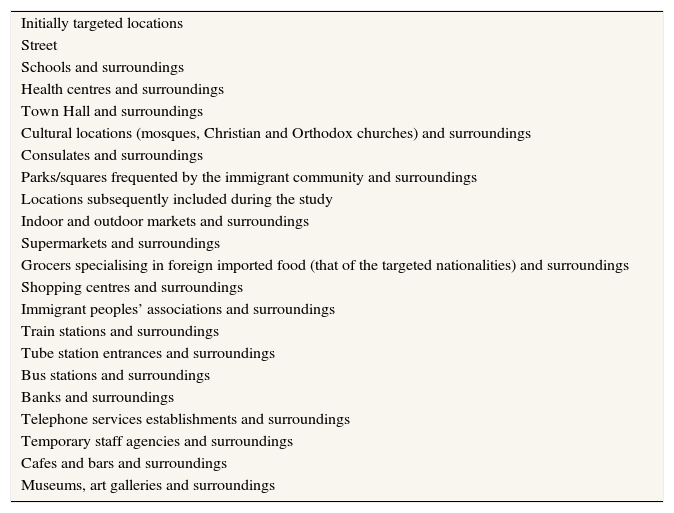

As a first safety measure, the research team decided not to conduct interviews in interviewees’ homes, but rather to try to find potential participants in the street. To this end, we designed and took routes which passed through the places which were most frequented by the group of women targeted according to information provided by public service and non-governmental organisation professionals. The interviewers and research team added other places to the final list (Table 1).

Locations included in the routes for targeting women for the violence against women study on Romanian, Moroccan, and Ecuadorian women (Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia, 2011–2012).

| Initially targeted locations |

| Street |

| Schools and surroundings |

| Health centres and surroundings |

| Town Hall and surroundings |

| Cultural locations (mosques, Christian and Orthodox churches) and surroundings |

| Consulates and surroundings |

| Parks/squares frequented by the immigrant community and surroundings |

| Locations subsequently included during the study |

| Indoor and outdoor markets and surroundings |

| Supermarkets and surroundings |

| Grocers specialising in foreign imported food (that of the targeted nationalities) and surroundings |

| Shopping centres and surroundings |

| Immigrant peoples’ associations and surroundings |

| Train stations and surroundings |

| Tube station entrances and surroundings |

| Bus stations and surroundings |

| Banks and surroundings |

| Telephone services establishments and surroundings |

| Temporary staff agencies and surroundings |

| Cafes and bars and surroundings |

| Museums, art galleries and surroundings |

It was also decided that interviews would only be conducted with women who were alone at the time of the interviews and who felt safe enough to express their opinions.

In addition, the interviews were not always conducted in the same place where the women had been found. Sometimes it was necessary to conduct the interview elsewhere, in order to provide the participant with more privacy and peace of mind. If another person appeared during an interview, such as someone who appeared to be her partner, the interview was abandoned as stipulated in the Putting Women First protocol. Although this situation only occurred in 0.2% of the interviews (8 of the 1637 interviews conducted), it was an essential measure in order to ensure the safety of the women involved.

Breaking the silence. Strategies for detecting cases of violence against womenAs with other sensitive topics, VAW situations tend to be silenced. Tackling this secrecy presents a challenge, and requires an exhaustive debate on the most effective strategies to be used in order to achieve better contact with the women concerned.

Our first strategy was to select interviewers from the same country of origin, or who spoke the same language as that of the interviewees in order to establish a closer relationship with the women concerned5. The Putting Women First protocol also formed part of the contents of the training session that interviewers received before starting interviews.

The second strategy was to administer the Index of Spouse Abuse (ISA) questionnaire in order to be able to target cases of VAW. It was used the version of this scale which was previously validated in Spanish with both, native and immigrant women.6,7

The decision to use a validated questionnaire in Spanish rather than the same questionnaire translated into the interviewees’ native language but not validated was based on the need to avoid biased calculations on the prevalence of VAW. This would have constituted a greater limitation than a linguistically-biased one. This decision was also in line with the Putting Women First protocol recommendation of using reliable methodology in research on the prevalence of gender-based violence.

In order to respect participants’ privacy, they answered the ISA questionnaire independently, and interviewers only assisted in questionnaire completion when requested to do so by participants who encountered linguistic difficulties.

Almost a third of the immigrant women targeted by the interviewers (1240 of a total of 3940) were excluded from the study, as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (partner, language, age, length of residence in Spain). In addition, 1078 women refused to participate or abandoned the interview, and 24 questionnaires were eliminated during the data-refinement stage. We do not know why some women refused to answer the survey. It could be a limitation of the study if some of these women were in situations of abuse and were subject to strict control by their partners. In total, 1607 questionnaires were completed. A response rate of 59.3% was obtained based upon the American Association for Public Opinion Research standard definition for response rate, type 2.8

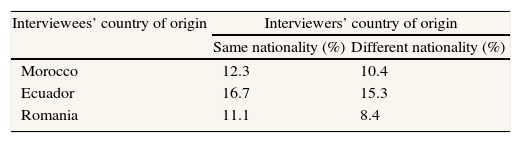

The prevalence of VAW last year was 11.7%, of which 15.6% corresponded to Ecuadorian women, 10.9% to Moroccan women, and 8.6% to Romanian women. Slight differences were observed when women had been interviewed by someone of a different nationality to that of their own. However, these were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Prevalence of violence against women according to the nationality of interviewers and interviewees (Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, 2011–2012).

| Interviewees’ country of origin | Interviewers’ country of origin | |

| Same nationality (%) | Different nationality (%) | |

| Morocco | 12.3 | 10.4 |

| Ecuador | 16.7 | 15.3 |

| Romania | 11.1 | 8.4 |

The prevalence differences between interviewers’ country of origin are not statistically significant for α=0.05 (ji-squared contrast).

VAW research is not based solely on the concept of gathering data. It also provides an opportunity to inform women of potential sources of support. The interviewers ensured that an atmosphere of safety and trust prevailed during field work, as some of the interviewees stated that they either were or had been in an abusive situation. The interviewers were well-informed with regard to listening to and informing the women in question. All women were given written information on local and national VAW helplines at the end of the interview, which would be able to provide further information on existing health, legal and social services and educational resources in the community –as recommended by the Putting Women First protocol.

A preliminary pilot study revealed that the women rejected a folio-sized VAW helpline leaflet. The problem was overcome by folding it up either once or several times, thus making it more discreet so that it could be safely put away without their partners noticing it –a suggestion made by the interviewers.

Future challengesAdherence to the Putting Women First protocol in a VAW study on Moroccan, Romanian and Ecuadorian women living in Spain prompted the research team to pay particular attention to the selection and training of interviewers, to design ideal routes for targeting the immigrant women in question and to devise the most effective strategies to ensure that the women's safety was not compromised prior to, during, or after taking part in the study. Among the limitations, the linguistic barriers encountered in this study should be highlighted. In future research on VAW using self-administered questionnaires, it would be more effective to employ questionnaires validated in the interviewees’ native tongue.

Author's contributionsThe signing authors have contributed to the conception of the study, design and interpretation of the data. Data analyses were carried out by J. Torrubiano-Dominguez with supervision of C. Vives-Cases. Both, the signing authors and collective signing, revised critically the successive drafts of the paper and contributed intellectually to its improvement. All the authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study has been funded by the Carlos III Institute and The Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness for the 2011–2012 period. It is also part of the Health and Immigration sub-programme of the CIBERESP.

Conflicts of interestThis paper will be used as part of J. Torrubiano Domínguez's PhD training programme and dissertation at the Universitat of Alicante, Spain. The second author of this article is on the editorial board of Gaceta Sanitaria but was not involved in the editorial process.

The authors are grateful to all women who have participated in this study, both interviewers and interviewees. The authors are also grateful to Dr. Elena Ronda-Pérez for her comments and suggestions to the final version of the manuscript.

Andrés Alonso Agudelo-Suárez (University of Antioquia, Colombia), Diana Gil-González (University of Alicante, Spain), Daniel La Parra Casado (University of Alicante, Spain), M. Carmen Davó (University of Alicante, Spain), M. Asunción Martínez-Román (University of Alicante, Spain), M Carmen Pérez-Belda (University of Alicante, Spain).