To estimate the prevalence of young people's involvement in violence measured as participation in physical fights or being physically, sexually or emotionally abused. We also aimed to understand the role of social, demographic and other behavioural characteristics in violence.

MethodsWe evaluated 7511 adolescents (4243 girls and 3268 boys) aged 15 to 19 years old, enrolled in public schools. Information was obtained using an anonymous, self-administrated questionnaire.

ResultsThe most frequently reported type of violence was emotional abuse (15.6%). Boys reported greater involvement in fights (3.6 vs. 13.6%, p<0.001) and physical abuse (7.5 vs. 19.5%, p<0.001). The prevalence of emotional abuse (16.2 vs. 14.8%, p=0.082) and sexual abuse (2.0 vs. 1.8%, p=0.435) was similar in girls and boys. After adjustment, increasing age decreased the odds of being involved in fights in both genders but increased the odds of emotional abuse. Living in a rented home was associated with physical abuse in girls (odds ratio [OR]: 1.4; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 1.0–1.9) and boys (OR: 1.6; 95%CI: 1.2–2.0). In girls the odds of being emotionally abused increased with greater parental education. Smoking and cannabis use were associated with all types of violence in both genders.

ConclusionsThe most frequently reported form of violence was emotional abuse. We found differences by gender, with boys reporting more physical abuse and involvement in fights. Adolescents whose parents had a higher educational level reported more physical and emotional abuse, which may be related to differences in the perception of abuse.

Estimar la prevalencia de la participación de los jóvenes en peleas, y de ser físicamente, sexualmente o emocionalmente maltratados. Analizar la función de las características sociales, demográficas y de comportamiento sobre la violencia.

MétodosSe evaluaron 7.511 adolescentes (4.243 chicas y 3.268 chicos) de 15 a 19 años de edad, matriculados en escuelas públicas. La información se obtuvo por cuestionario anónimo auto-administrado.

ResultadosLa violencia emocional fue la más notificada (15,6%). Los chicos indicaron más peleas (3,6 frente a 13,6%, p<0,001) y maltrato físico (7,5 frente a 19.5%, p<0,001). La prevalencia de maltrato emocional (16,2% frente a 14,8%, p=0,082) y abuso sexual (2,0 frente a 1.8%, p=0,435) fue similar en chicos y chicas. Después del ajuste, en ambos sexos, la edad disminuye las probabilidades de participar en peleas, y aumenta las probabilidades de abuso emocional. Vivir en una casa alquilada se asoció con el abuso físico (odds ratio [OR]: 1,4 intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%]: 1,0–1,9) en las chicas y OR: 1,6; IC95%: 1,2–2,0 en los chicos. En las chicas la probabilidad de abuso emocional aumenta con la educación de sus padres. El tabaquismo y el consumo de cannabis se asociaron con todos los tipos de violencia, en ambos sexos.

ConclusionesLa violencia con mayor prevalencia es la emocional. Encontramos diferencias por sexo, con los chicos notificando más abuso físico y participación en peleas. Los adolescentes cuyos padres tienen más educación indican más abuso físico y emocional, lo que podría estar relacionado con diferencias en la percepción de abuso.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) it is estimated that, annually, more than one million individuals lose their life as consequence of violence, mostly related to accidents or suicide with more impact in young ages.1 Adolescent's violent behaviour is considered a major worldwide public health problem, associated with serious physical and psychosocial consequences.1–7

However, there is still limited information on violence in adolescence, particularly about behaviours with less physical impact. Occasional fighting even with less physical consequences, could be a symptom of other kinds of violence, since it is a relatively common behaviour among youth that often are both perpetrators and/or victims of violence,6,7 showing a close link between forms of violence. Adolescents’ victims of some kind of violence are more likely to promote violent acts than those who were not exposed to it8–11 and therefore this is a way of perpetuating the cycle of violence.

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children project (HBSC) coordinated by the WHO provides information on young people's health, namely violence and related behaviours, for a considerable number of countries.12 In this study the prevalence of adolescents that reported involvement in fights vary, respectively in girls and boys, from 7.2 to 37.5% and 34.9 to 74.3% at 11 years of age and from 11.2 to 32.6% and 29.4 to 62.7% at 15. In Portugal, in 2005/2006, according to the same study at the age of 15 year-old, 7.2% of the boys and 1.4% of the girls had already been involved in fights three or more times in the 12 months before the evaluation.13 These data showed that this is a common problem with great variability between countries.

Demographic, social and cultural characteristics have also shown association with violent behaviour.14 However and despite of social, cultural and economic differences between countries, adolescents seem to behave similarly in their expression of violence, namely the relation with alcohol drinking, tobacco consumption and academic achievement.15 Yet, the same diversity of factors related with violence and its different relevance in different populations can explain the differences found between countries.

Although there are some known factors associated with violence, most studies evaluate only acts of violence with serious consequences which is recognized as the tip of the iceberg and could not represent the real dimension of the problem. Thus, it is important to monitor not only severe situations but also those not usually reported in adolescents, in each specific context, in order to show a snapshot of the problem and to contribute to the development of effective preventive approaches.

We designed a national cross-sectional survey to estimate the prevalence of youth involvement in violence measured as participation in physical fights or being physically, sexually or emotionally abused. Also, we intended to understand the role of social, demographic and behavioural characteristics leading to violent acts, analysing the effect of parents’ education, type of residence, attendance to religious’ services and other behavioural characteristics on violence.

MethodsParticipants and data collectionEligible participants were all students aged 15 to 19 years old attending one selected public school representing each of the 18 country county capitals. Schools were randomly selected between all public schools in each county capital. All executive boards of the selected schools were contacted, the study was presented and each school decided about the participation. The selected schools of two counties refused permission to approach their students and were not replaced. Thus data were collected for the remaining 16 schools during the 2000 academic year.

Information was obtained using a self-administered structured and anonymous questionnaire, which comprised social and demographic characteristics, such as parents’ education, attendance to religious service and school failure. As well as the information on violence, the questionnaire also included information on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drugs consumption. It was also asked if the participant was sexually active, meaning adolescents who had ever had sexual intercourse.

In each school the students answered the questionnaire in the classroom with the presence of the teacher or the study responsible.

Since it was an anonymous questionnaire no individual consent was obtained from the parents, the consent to participate was given by the parents’ association represented in the school executive board. Adolescents were informed during the study presentation that it was a voluntary participation and that it was allowed for them to answer only parts of the questionnaire or to place the questionnaire in blank in the ballot box. When finished, the questionnaire without any identification was placed in a closed container present in the classroom. Students that were not present in the day when the evaluation was performed were not called to answer it on another day. All questionnaires were sent to the Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology of Porto Medical School to perform the data entry and analysis.

A total of 8,484 adolescents were addressed but 429 refused to participate and 123 gave inconsistent answers. From the 7,932 remaining students our final sample comprised 7,511 (95%) that provided information for the key questions (4,243 girls and 3,268 boys).

Data analysisThe main outcomes addressed in this study were defined according to the positive answers to the following four questions: «Have you ever been involved in fights during the last month?», and «Have you ever been victim of physical, sexual or emotional abuse?». Adolescents’ answers regarding the three types of abuse (physical, sexual and emotional) were given according to their self perception and no definition of these variables was provided.

For analysis it was considered only two categories for each behaviour: never frente a ever. Parents’ education level was determined in years of school attendance of parents, for which prevailed the highest level.

Proportions were compared using the Chi-square test. The association between independent variables, physical fights and physical, sexual or emotional abuse was estimated by crude and adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (95%CI) using unconditional logistic regression, performed separately for each gender, adjusted for age, parents’ education, type of residence, attendance to religious services, school failure and behavioural characteristics. For all analysis we considered the level of significance of 5%.

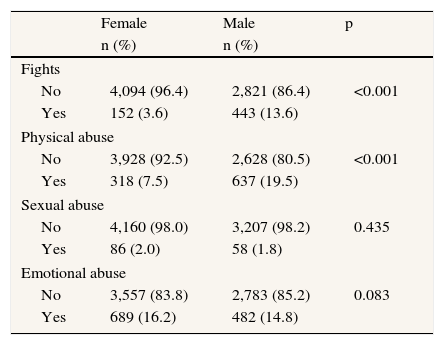

ResultsOverall, 595 (7.9%) adolescents reported involvement in fights during the last month. Emotional abuse was reported by 15.6% of the adolescents and physical and sexual abuse by 12.7% and 1.9%, respectively. After weighting for population, the prevalence of physical fighting and physical, sexual or emotional abuse was similar across the country. Compared with girls, boys reported more frequently involvement in fights (13.6 vs. 3.6%, p<0.001) and physical abuse (19.5 vs. 7.5%, p<0.001). No significant differences between genders were found for emotional abuse (16.2 vs. 14.8%, p=0.082) and sexual abuse (2.0 vs. 1.8%, p=0.435), girls and boys respectively (table 1).

Prevalence of fights, physical, sexual and emotional abuse among adolescents in Portugal

| Female | Male | p | |

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Fights | |||

| No | 4,094 (96.4) | 2,821 (86.4) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 152 (3.6) | 443 (13.6) | |

| Physical abuse | |||

| No | 3,928 (92.5) | 2,628 (80.5) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 318 (7.5) | 637 (19.5) | |

| Sexual abuse | |||

| No | 4,160 (98.0) | 3,207 (98.2) | 0.435 |

| Yes | 86 (2.0) | 58 (1.8) | |

| Emotional abuse | |||

| No | 3,557 (83.8) | 2,783 (85.2) | 0.083 |

| Yes | 689 (16.2) | 482 (14.8) | |

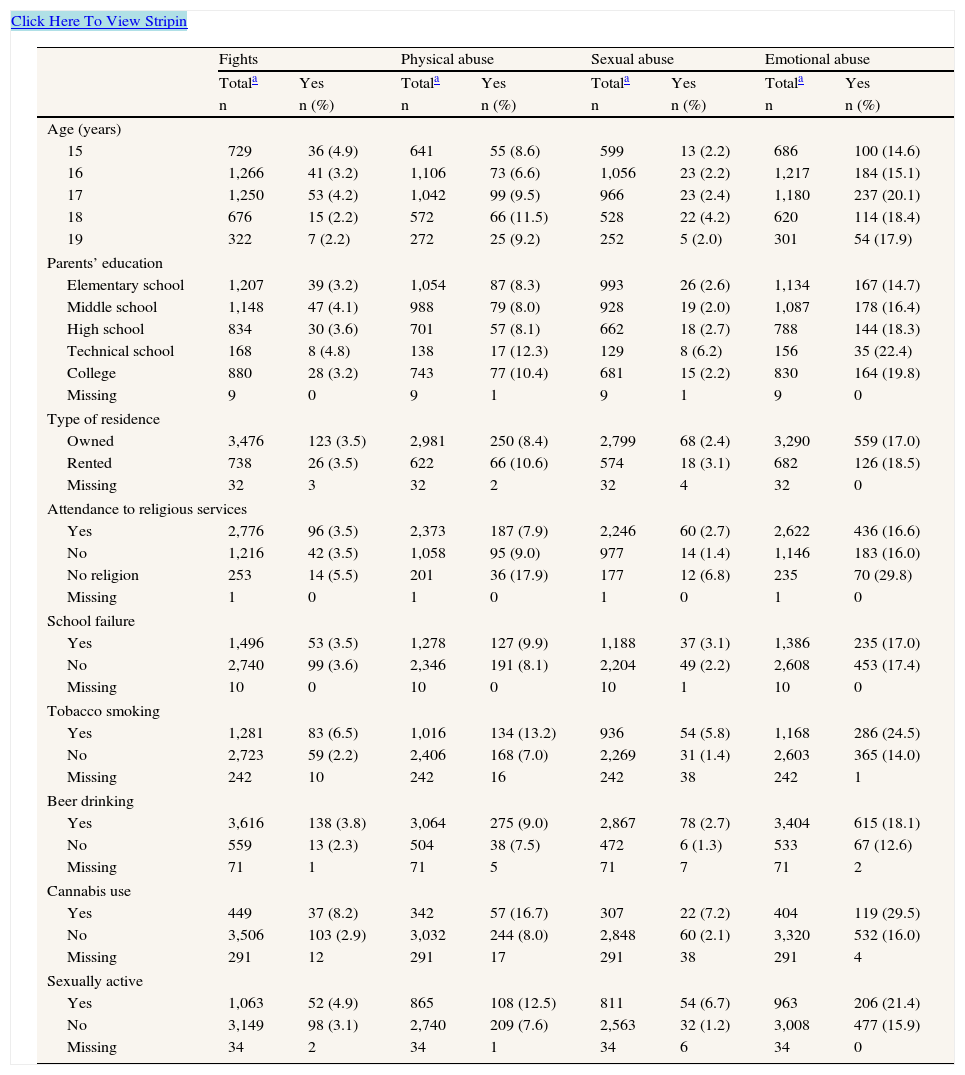

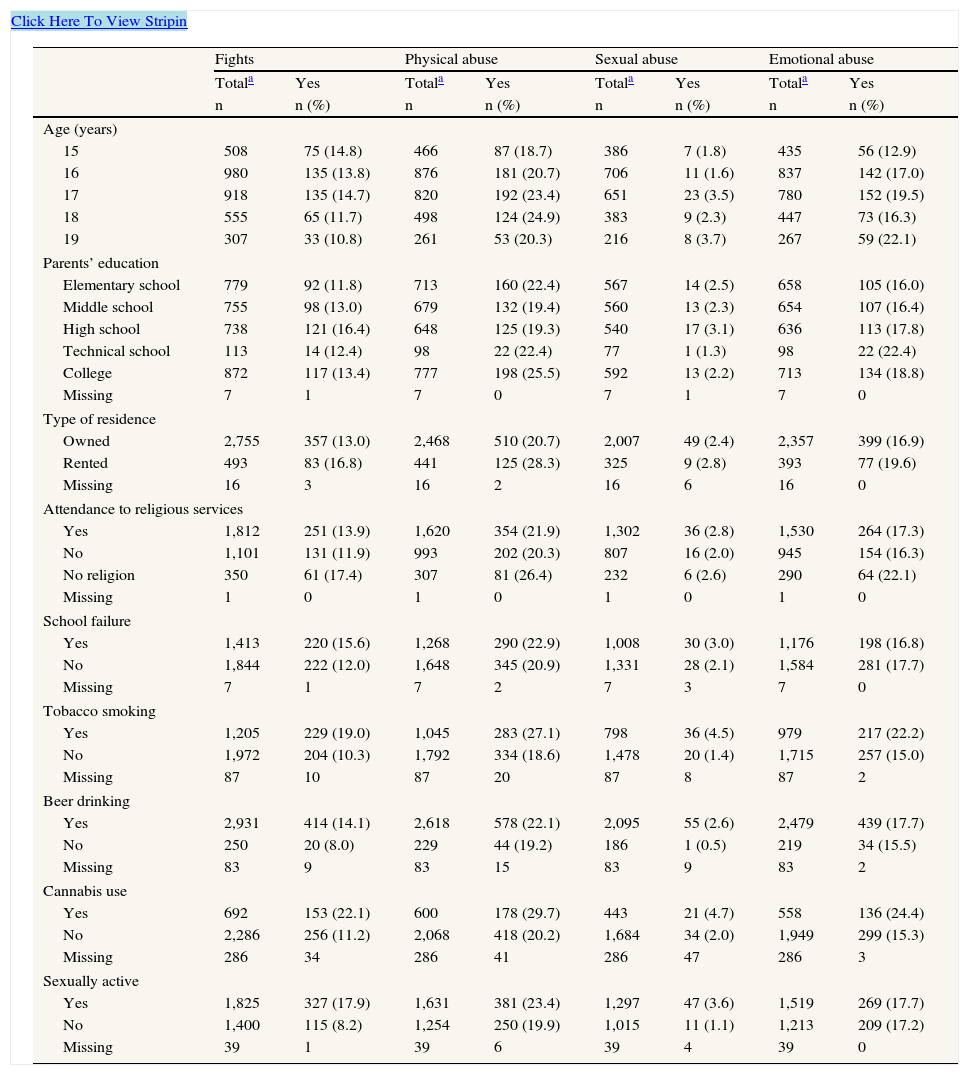

Tables 2 and 3 show the prevalence of fights, physical, sexual and emotional abuse according to age, parents’ education, type of residence, religion, school failure, tobacco smoking, beer drinking, cannabis use and sexual behaviour.

Prevalence of fights, physical, sexual and emotional abuse among girls in Portugal

| Fights | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Emotional abuse | |||||

| Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | |

| n | n (%) | n | n (%) | n | n (%) | n | n (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 15 | 729 | 36 (4.9) | 641 | 55 (8.6) | 599 | 13 (2.2) | 686 | 100 (14.6) |

| 16 | 1,266 | 41 (3.2) | 1,106 | 73 (6.6) | 1,056 | 23 (2.2) | 1,217 | 184 (15.1) |

| 17 | 1,250 | 53 (4.2) | 1,042 | 99 (9.5) | 966 | 23 (2.4) | 1,180 | 237 (20.1) |

| 18 | 676 | 15 (2.2) | 572 | 66 (11.5) | 528 | 22 (4.2) | 620 | 114 (18.4) |

| 19 | 322 | 7 (2.2) | 272 | 25 (9.2) | 252 | 5 (2.0) | 301 | 54 (17.9) |

| Parents’ education | ||||||||

| Elementary school | 1,207 | 39 (3.2) | 1,054 | 87 (8.3) | 993 | 26 (2.6) | 1,134 | 167 (14.7) |

| Middle school | 1,148 | 47 (4.1) | 988 | 79 (8.0) | 928 | 19 (2.0) | 1,087 | 178 (16.4) |

| High school | 834 | 30 (3.6) | 701 | 57 (8.1) | 662 | 18 (2.7) | 788 | 144 (18.3) |

| Technical school | 168 | 8 (4.8) | 138 | 17 (12.3) | 129 | 8 (6.2) | 156 | 35 (22.4) |

| College | 880 | 28 (3.2) | 743 | 77 (10.4) | 681 | 15 (2.2) | 830 | 164 (19.8) |

| Missing | 9 | 0 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 1 | 9 | 0 |

| Type of residence | ||||||||

| Owned | 3,476 | 123 (3.5) | 2,981 | 250 (8.4) | 2,799 | 68 (2.4) | 3,290 | 559 (17.0) |

| Rented | 738 | 26 (3.5) | 622 | 66 (10.6) | 574 | 18 (3.1) | 682 | 126 (18.5) |

| Missing | 32 | 3 | 32 | 2 | 32 | 4 | 32 | 0 |

| Attendance to religious services | ||||||||

| Yes | 2,776 | 96 (3.5) | 2,373 | 187 (7.9) | 2,246 | 60 (2.7) | 2,622 | 436 (16.6) |

| No | 1,216 | 42 (3.5) | 1,058 | 95 (9.0) | 977 | 14 (1.4) | 1,146 | 183 (16.0) |

| No religion | 253 | 14 (5.5) | 201 | 36 (17.9) | 177 | 12 (6.8) | 235 | 70 (29.8) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| School failure | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,496 | 53 (3.5) | 1,278 | 127 (9.9) | 1,188 | 37 (3.1) | 1,386 | 235 (17.0) |

| No | 2,740 | 99 (3.6) | 2,346 | 191 (8.1) | 2,204 | 49 (2.2) | 2,608 | 453 (17.4) |

| Missing | 10 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| Tobacco smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,281 | 83 (6.5) | 1,016 | 134 (13.2) | 936 | 54 (5.8) | 1,168 | 286 (24.5) |

| No | 2,723 | 59 (2.2) | 2,406 | 168 (7.0) | 2,269 | 31 (1.4) | 2,603 | 365 (14.0) |

| Missing | 242 | 10 | 242 | 16 | 242 | 38 | 242 | 1 |

| Beer drinking | ||||||||

| Yes | 3,616 | 138 (3.8) | 3,064 | 275 (9.0) | 2,867 | 78 (2.7) | 3,404 | 615 (18.1) |

| No | 559 | 13 (2.3) | 504 | 38 (7.5) | 472 | 6 (1.3) | 533 | 67 (12.6) |

| Missing | 71 | 1 | 71 | 5 | 71 | 7 | 71 | 2 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||||

| Yes | 449 | 37 (8.2) | 342 | 57 (16.7) | 307 | 22 (7.2) | 404 | 119 (29.5) |

| No | 3,506 | 103 (2.9) | 3,032 | 244 (8.0) | 2,848 | 60 (2.1) | 3,320 | 532 (16.0) |

| Missing | 291 | 12 | 291 | 17 | 291 | 38 | 291 | 4 |

| Sexually active | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,063 | 52 (4.9) | 865 | 108 (12.5) | 811 | 54 (6.7) | 963 | 206 (21.4) |

| No | 3,149 | 98 (3.1) | 2,740 | 209 (7.6) | 2,563 | 32 (1.2) | 3,008 | 477 (15.9) |

| Missing | 34 | 2 | 34 | 1 | 34 | 6 | 34 | 0 |

Prevalence of fights, physical, sexual and emotional abuse among boys in Portugal

| Fights | Physical abuse | Sexual abuse | Emotional abuse | |||||

| Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | Totala | Yes | |

| n | n (%) | n | n (%) | n | n (%) | n | n (%) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 15 | 508 | 75 (14.8) | 466 | 87 (18.7) | 386 | 7 (1.8) | 435 | 56 (12.9) |

| 16 | 980 | 135 (13.8) | 876 | 181 (20.7) | 706 | 11 (1.6) | 837 | 142 (17.0) |

| 17 | 918 | 135 (14.7) | 820 | 192 (23.4) | 651 | 23 (3.5) | 780 | 152 (19.5) |

| 18 | 555 | 65 (11.7) | 498 | 124 (24.9) | 383 | 9 (2.3) | 447 | 73 (16.3) |

| 19 | 307 | 33 (10.8) | 261 | 53 (20.3) | 216 | 8 (3.7) | 267 | 59 (22.1) |

| Parents’ education | ||||||||

| Elementary school | 779 | 92 (11.8) | 713 | 160 (22.4) | 567 | 14 (2.5) | 658 | 105 (16.0) |

| Middle school | 755 | 98 (13.0) | 679 | 132 (19.4) | 560 | 13 (2.3) | 654 | 107 (16.4) |

| High school | 738 | 121 (16.4) | 648 | 125 (19.3) | 540 | 17 (3.1) | 636 | 113 (17.8) |

| Technical school | 113 | 14 (12.4) | 98 | 22 (22.4) | 77 | 1 (1.3) | 98 | 22 (22.4) |

| College | 872 | 117 (13.4) | 777 | 198 (25.5) | 592 | 13 (2.2) | 713 | 134 (18.8) |

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 0 |

| Type of residence | ||||||||

| Owned | 2,755 | 357 (13.0) | 2,468 | 510 (20.7) | 2,007 | 49 (2.4) | 2,357 | 399 (16.9) |

| Rented | 493 | 83 (16.8) | 441 | 125 (28.3) | 325 | 9 (2.8) | 393 | 77 (19.6) |

| Missing | 16 | 3 | 16 | 2 | 16 | 6 | 16 | 0 |

| Attendance to religious services | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,812 | 251 (13.9) | 1,620 | 354 (21.9) | 1,302 | 36 (2.8) | 1,530 | 264 (17.3) |

| No | 1,101 | 131 (11.9) | 993 | 202 (20.3) | 807 | 16 (2.0) | 945 | 154 (16.3) |

| No religion | 350 | 61 (17.4) | 307 | 81 (26.4) | 232 | 6 (2.6) | 290 | 64 (22.1) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| School failure | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,413 | 220 (15.6) | 1,268 | 290 (22.9) | 1,008 | 30 (3.0) | 1,176 | 198 (16.8) |

| No | 1,844 | 222 (12.0) | 1,648 | 345 (20.9) | 1,331 | 28 (2.1) | 1,584 | 281 (17.7) |

| Missing | 7 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 0 |

| Tobacco smoking | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,205 | 229 (19.0) | 1,045 | 283 (27.1) | 798 | 36 (4.5) | 979 | 217 (22.2) |

| No | 1,972 | 204 (10.3) | 1,792 | 334 (18.6) | 1,478 | 20 (1.4) | 1,715 | 257 (15.0) |

| Missing | 87 | 10 | 87 | 20 | 87 | 8 | 87 | 2 |

| Beer drinking | ||||||||

| Yes | 2,931 | 414 (14.1) | 2,618 | 578 (22.1) | 2,095 | 55 (2.6) | 2,479 | 439 (17.7) |

| No | 250 | 20 (8.0) | 229 | 44 (19.2) | 186 | 1 (0.5) | 219 | 34 (15.5) |

| Missing | 83 | 9 | 83 | 15 | 83 | 9 | 83 | 2 |

| Cannabis use | ||||||||

| Yes | 692 | 153 (22.1) | 600 | 178 (29.7) | 443 | 21 (4.7) | 558 | 136 (24.4) |

| No | 2,286 | 256 (11.2) | 2,068 | 418 (20.2) | 1,684 | 34 (2.0) | 1,949 | 299 (15.3) |

| Missing | 286 | 34 | 286 | 41 | 286 | 47 | 286 | 3 |

| Sexually active | ||||||||

| Yes | 1,825 | 327 (17.9) | 1,631 | 381 (23.4) | 1,297 | 47 (3.6) | 1,519 | 269 (17.7) |

| No | 1,400 | 115 (8.2) | 1,254 | 250 (19.9) | 1,015 | 11 (1.1) | 1,213 | 209 (17.2) |

| Missing | 39 | 1 | 39 | 6 | 39 | 4 | 39 | 0 |

The prevalence of being involved in fights in girls and boys is higher in younger ages but the opposite occurs for physical, emotional and sexual abuse (tables 2 and 3).

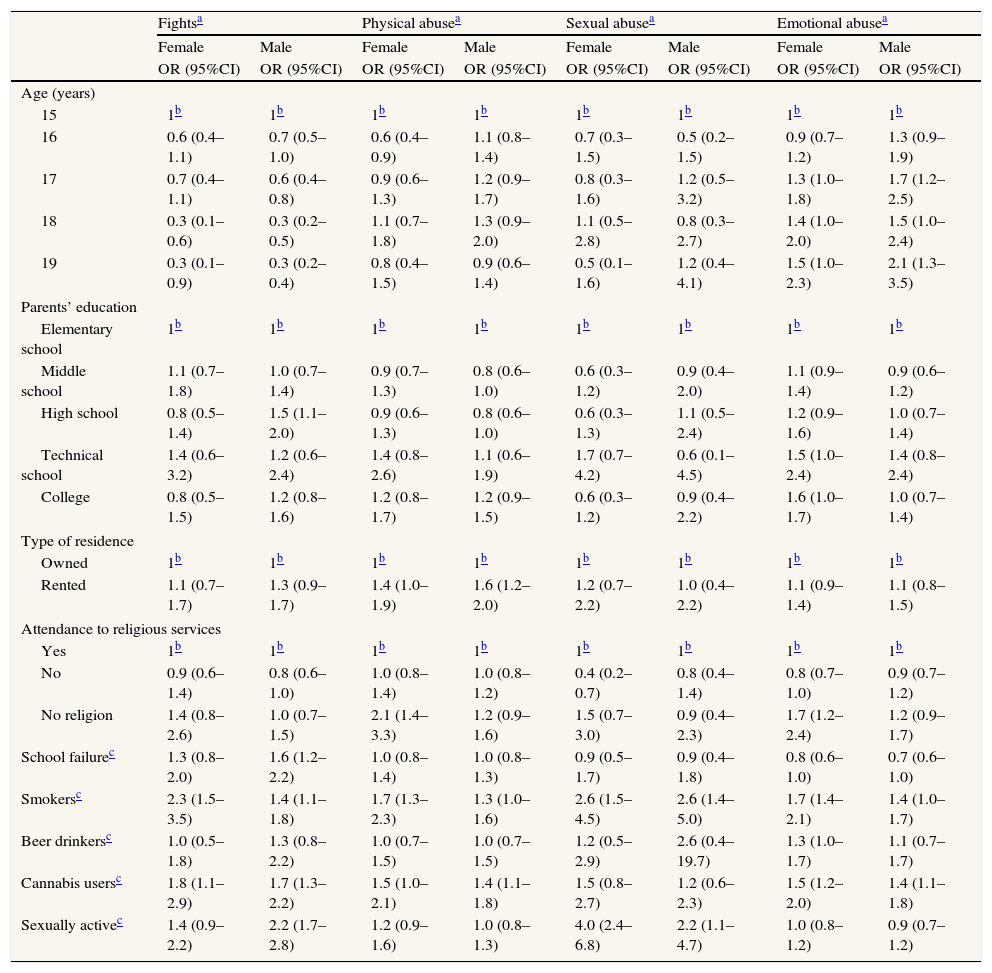

After adjustment, in both genders increasing age decreases the odds to be involved in fights but increases the odds for emotional abuse. No significant association was found with age and physical or sexual abuse. School failure was associated with fights only in boys, OR:1.6; 95%CI: 1.2–2.2 (table 4).

Odds ratio of fights, physical, sexual and emotional abuse in adolescents according to socio-demographic and behavioural characteristics

| Fightsa | Physical abusea | Sexual abusea | Emotional abusea | |||||

| Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | |

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| 15 | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b |

| 16 | 0.6 (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 (0.5–1.0) | 0.6 (0.4–0.9) | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 0.7 (0.3–1.5) | 0.5 (0.2–1.5) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) |

| 17 | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 0.8 (0.3–1.6) | 1.2 (0.5–3.2) | 1.3 (1.0–1.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) |

| 18 | 0.3 (0.1–0.6) | 0.3 (0.2–0.5) | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.3 (0.9–2.0) | 1.1 (0.5–2.8) | 0.8 (0.3–2.7) | 1.4 (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) |

| 19 | 0.3 (0.1–0.9) | 0.3 (0.2–0.4) | 0.8 (0.4–1.5) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.5 (0.1–1.6) | 1.2 (0.4–4.1) | 1.5 (1.0–2.3) | 2.1 (1.3–3.5) |

| Parents’ education | ||||||||

| Elementary school | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b |

| Middle school | 1.1 (0.7–1.8) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) | 0.9 (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.9 (0.4–2.0) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) |

| High school | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 1.5 (1.1–2.0) | 0.9 (0.6–1.3) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.6 (0.3–1.3) | 1.1 (0.5–2.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| Technical school | 1.4 (0.6–3.2) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 1.1 (0.6–1.9) | 1.7 (0.7–4.2) | 0.6 (0.1–4.5) | 1.5 (1.0–2.4) | 1.4 (0.8–2.4) |

| College | 0.8 (0.5–1.5) | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 1.2 (0.8–1.7) | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.9 (0.4–2.2) | 1.6 (1.0–1.7) | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| Type of residence | ||||||||

| Owned | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b |

| Rented | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.3 (0.9–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 1.6 (1.2–2.0) | 1.2 (0.7–2.2) | 1.0 (0.4–2.2) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) |

| Attendance to religious services | ||||||||

| Yes | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b | 1b |

| No | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.4 (0.2–0.7) | 0.8 (0.4–1.4) | 0.8 (0.7–1.0) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

| No religion | 1.4 (0.8–2.6) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 2.1 (1.4–3.3) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.5 (0.7–3.0) | 0.9 (0.4–2.3) | 1.7 (1.2–2.4) | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) |

| School failurec | 1.3 (0.8–2.0) | 1.6 (1.2–2.2) | 1.0 (0.8–1.4) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.9 (0.4–1.8) | 0.8 (0.6–1.0) | 0.7 (0.6–1.0) |

| Smokersc | 2.3 (1.5–3.5) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 1.3 (1.0–1.6) | 2.6 (1.5–4.5) | 2.6 (1.4–5.0) | 1.7 (1.4–2.1) | 1.4 (1.0–1.7) |

| Beer drinkersc | 1.0 (0.5–1.8) | 1.3 (0.8–2.2) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 1.2 (0.5–2.9) | 2.6 (0.4–19.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) |

| Cannabis usersc | 1.8 (1.1–2.9) | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | 1.5 (1.0–2.1) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 1.5 (0.8–2.7) | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) |

| Sexually activec | 1.4 (0.9–2.2) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 4.0 (2.4–6.8) | 2.2 (1.1–4.7) | 1.0 (0.8–1.2) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

Considering social-economic characteristics, boys whose parents had high school education have a higher probability to be involved in fights OR:1.5; 95%CI: 1.1–2.0.

In girls, we found increasing odds of being emotionally abused in the upper parent's class education (table 4). The other marker, living in a rented house, was associated with physical abuse in girls, OR:1.4; 95%CI: 1.0–1.9, and in boys, OR:1.6; 95%CI: 1.2–2.0 (table 4).

Self-classification as «no religion» is related with higher involvement in violence, and significant only in girls for physical and emotional abuse (table 4).

Considering behavioural characteristics, smoking and cannabis consumption was associated with violence in both genders, regardless the violence indicator. Being sexually active was significantly associated with being involved in fights in boys and being victim of sexual abuse in both (girls OR:4.0; 95%CI: 2.4–6.8; boys OR:2.2; 95%CI: 1.1–4.7) (table 4).

DiscussionIn our national sample, about 8% of the adolescents reported to be involved in a fight in the last month. In line with the results from other studies, our results also showed that boys were more frequently involved in fights than girls and this is true for all ages evaluated.7,13,16,17 Though this doesn’t mean that boys are more aggressive than girls, it can reflect cultural patterns where it is expected for them to be involved in issues of power and aggression, meaning to be involved in fights but also to be victim of physical abuse.

We also found that being involved in fights is more frequent in young people, which is in agreement with adolescent involvement with violence beginning at increasingly younger ages.1,18 This could represent a marker for future increasing risk to be involved in more severe acts of violence. However, the cross-sectional nature of our study doesn’t allow answering this question.

On the other hand, reported emotional abuse increase with age which can imply a real increase with age or those older adolescents may be more able to understand it as violence and report it more often. Although, in general less studied, emotional abuse was reported by an important number of adolescents which addresses its relevance.

We found that adolescents who live in rented houses have greater odds of being victim of physical abuse. This must be framed in the Portuguese context because the common intent in Portugal is to be able to buy a house, therefore renting means not having the possibility to achieve that goal. Thus, these data support that the social class that most feel this type of abuse is that with lower level (the poorest).19 Though a very interesting aspect, and apparently reversal result, is the association according to parents’ education, another socioeconomic indicator. These apparently contradictory results come from the possibility of creating four categories according to parents’ education while the type of residence is only discriminated in two groups, the poorest and the others which represent the majority of the adolescents (83.5%). When we used parents’ education we could have a better discrimination of all population and the apparently increase with parents’ education may actually indicate a higher prevalence of abuse or on the other hand these adolescent's value as abuse situations that socioeconomically disadvantaged adolescents wouldn’t.20 However, as it was not possible to obtain a description of the situations where the adolescent was involved we cannot discard any of the hypotheses.

Adolescents with parents with higher education level reported more often emotional abuse. This association could also happen because for higher social classes is easier to identify emotional abuse. On the other hand, if those in the lower classes were more subjected to physical violence they19 could have underweighted the emotional one. These results must be seen as part of a larger process in which family, social, peer and individual factors play an active role.21

In our study we found an association between adolescents who reported having no religion and being victim of physical and emotional abuse. Although this result was only significant for girls, is in accordance with previous studies that have demonstrated influences of religion on adolescents behaviours since they are involved in a set of values, rules that subjectively lays pressure in their conduct.22,23

It is known that being involved in risk behaviours like drugs or alcohol consumption is strongly associated with violence due to common determinants or because these behaviours are themselves promoters of violent situations.24,25 The present study also found that cannabis and smoking use were strongly associated with involvement in violent acts. Nevertheless, the association was weaker than the reported by other studies, probably because our «ever» class included those who have experimented and it was not possible to do an analysis taking into account the gradient of exposure.

The strongest association that we have found was the association between being sexually active and reported sexual abuse. The cross-sectional nature of our study doesn’t allow us to know if adolescents are sexually active because they are sexually abused or the opposite. Nevertheless some studies point out an association between sexual abuse and sexual behaviour, although this is not a linear relation and could be influenced by several aspects such as environmental or individual ones.26,27

Besides our interesting results, some limitations are present in our study. First of all the cross-sectional approach did not allow us to know if the related factors are determinants or consequences. Future research should add a longitudinal aspect. Another factor is the known tendency to underreport severe offences such as sexual ones when we are studying this problem.28 We recognize that our study may also have this bias; however the use of anonymous self-administered questionnaires was an attempt to minimize it. On the other hand, this option brought us less detailed information. We only analysed if the adolescent was ever a victim and we didn’t have information on the severity and frequency of the situation. Nevertheless, to obtain this information in sufficient detail to allow its understanding would be impossible for such a large number of adolescents. So we choose to have less information but a larger number of adolescents with the intent to be the basis for future research. For this purpose we also do not have information about with whom the adolescent fought, the nature of his involvement and the location of the fight.

Another limitation is the restriction to adolescents enrolled in schools that could not represent the whole of this group. In this context we hope that the selection of a school situated in the county capital had a small effect because in the levels of education represented in this study a large proportion of students of the surrounding regions (rural regions) went to schools in the county capital.

A strength of our study is the sample size, that through a stratified sample, made the findings a good estimation of the measured prevalences. It is also important to enhance the anonymity of the questionnaire which allowed us to obtain information for a larger number of adolescents and probably more accurate that in a face-to-face interview. What's more, there was a wide range of variables assessed to give a snapshot of the population. Also, the consistency of our results with other studies supports the validity of the information.

These findings are mainly significant as violence is a relatively common behaviour among adolescents and being a victim of physical, sexual or psychological abuse is a known risk factor for the development of adolescent's self-esteem, self-reliance, interpersonal relations and trust29. Our results also strengthen the importance of emotional abuse, usually less studied, but one of the most reported by the adolescents. In order to a better use of our results it would be important to understand the perception of violence according to social class to recognize the influence of these perceptions in adolescents’ answers and the consequent demand for support.

Conflict of interest statementNone declared

Financial supportNone declared

ContributorsH. Barros conceived the study and all the aspects to conduct it. T. Correia obtained the data and supervised logistic matters. S. Sousa analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. H. Barros, E. Ramos and S.Fraga contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript. All the authors provided ideas, interpreted the findings and revised subsequent drafts of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version. S. Sousa is the guarantor.