We aimed to estimate regional inequalities in excess deaths and premature mortality in Spain during 2020 and 2021, before high vaccination coverage against COVID-19.

MethodWith data from the National Institute of Statistics, within each region, sex, and age group, we estimated the excess deaths, the change in life expectancy at birth (e0) and age 65 (e65) and years of life lost as the difference between the observed and expected deaths using a time series analysis of 2015-2019 data and life expectancies based on Lee-Carter forecasting using 2010-2019 data.

ResultsFrom January 2020 to June 2021, an estimated 89,200 (men: 48,000; women: 41,200) excess deaths occurred in Spain with a substantial regional variability (highest in Madrid: 22,000, lowest in Canary Islands: −210). The highest reductions in e0 in 2020 were observed in Madrid (men −3.58 years, women −2.25), Castile-La Mancha (−2.72, −2.38), and Castile and Leon (−2.13, −1.39). During the first half of 2021, the highest reduction in e0 was observed in Madrid for men (−2.09; −2.37 to −1.84) and Valencian Community for women (−1.63; −1.97 to −1.3). The highest excess years of life lost in 2020 was in Castile-La Mancha (men: 5370; women: 3600, per 100 000). We observed large differences between reported COVID-19 deaths and estimated excess deaths across the Spanish regions.

ConclusionsRegions performed highly unequally on excess deaths, life expectancy and years of life lost. The investigation of the root causes of these regional inequalities might inform future pandemic policy in Spain and elsewhere.

Estimar las desigualdades regionales en exceso de muertes y mortalidad prematura en España entre enero de 2020 y junio de 2021, antes de la vacunación poblacional masiva contra la COVID-19.

MétodoCon datos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística se estimaron el exceso de muertes con respecto a las muertes esperadas por regione, sexo y grupos de edad, el cambio en la esperanza de vida al nacer (e0) y a los 65 años (e65), y los años de vida perdidos, mediante series temporales (2015-2019) y el pronóstico de Lee-Carter (2010-2019).

ResultadosEn el periodo del estudio, el exceso de muertes fue de 89.200 (hombres 48.000, mujeres 41.200), con una gran variabilidad regional (desde Madrid con 22.000 hasta las Islas Canarias con −210). Las mayores reducciones de e0 en 2020 fueron en Madrid (hombres −3,58 años, mujeres −2,25), Castilla-La Mancha (−2,72, −2,38) y Castilla y León (−2,13, −1,39), y en el primer semestre de 2021 fueron en Madrid (hombres −2,09; −2,37 a −1,84) y en la Comunidad Valenciana (mujeres −1,63; −1,97 a −1,3). El mayor exceso de años de vida perdidos en 2020 se produjo en Castilla-La Mancha (hombres 5370, mujeres 3600, por 100.000). Hubo grandes diferencias entre las muertes por COVID-19 notificadas y el exceso de muertes.

ConclusionesSe observaron enormes desigualdades regionales en el exceso de muertes, la esperanza de vida y los años de vida perdidos. La determinación de las causas fundamentales de estas desigualdades podría servir para mejorar las políticas de salud pública en pandemias futuras.

Following the emergence of COVID-19, countries and jurisdictions employed a wide range of public health policy interventions to minimise its impact.1 These measures affected many socioeconomic determinants of health, including healthcare.2 Identifying regional inequalities in the impact of the pandemic is important to inform future public health policy. A report by the European Committee on excess deaths in 2020 compared to the average number of deaths between 2016 and 2019 showed large differences across regions in Europe.3 However, this report did not take into account mortality improvements that had occurred in the years leading up to 2020 or seasonal trends by age and sex in each European region.

‘Excess deaths’ (observed minus expected deaths) has been considered the gold standard for estimating the overall impact of the pandemic, as robust data on all-cause mortality are less sensitive to misclassification errors in designating the cause of deaths.4 Indeed, large differences have been reported between reported COVID-19 deaths and estimated excess deaths associated with the pandemic.5,6 Higher COVID-19 mortality rates in males have been observed in Spain and elsewhere.7,8

‘Excess deaths’ does not consider age at death, which has an impact on the number of remaining years of life lost.9,10 Analysis of life expectancy (LE) and years of life lost (YLL) provides a more detailed estimation of premature mortality. LE is an indication of the average number of years that people can expect to survive if age-specific death rates for that year remain unchanged for the rest of their lives.11,12 Analysis of LE at age 65 is of particular relevance given that older people are much more vulnerable to COVID-19. YLL estimates the average number of expected life years for an individual at the time of death.10 An analysis of excess deaths, LE, and YLL would provide a comprehensive examination of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Spain is among the countries with the highest estimated total excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic between January 2020 and December 2021 according to the World Health Organisation (WHO).13 It ranks second in loss of life expectancy in a study of 29 countries.14 The study of the impact of COVID-19 mortality at the subnational level can provide essential public health information, especially in countries where regions have a large degree of independence in healthcare decision-making, as is the case in Spain.15 A detailed spatial analysis allows a more accurate and nuanced assessment of disparities in excess mortality, which are often masked when considering national aggregates.16 In Spain, variations in excess deaths at a regional level have been reported,6,17,18 showing that crude rates of excess death were highest in Castile-La Mancha, Madrid and Castile and Leon; however, regional differences in premature mortality have not yet been described. Examining geographical variations in COVID-19 mortality in politically defined regions with full population healthcare responsibilities would be useful in identifying best practices to inform decision-making.

We aimed to report excess deaths, changes in LE and changes in YLL associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in regions of Spain considering temporal trends and seasonal variations in mortality within regions from January 2020 through June 2021. We chose this period because, by the end of June 2021, the majority of the Spanish population was vaccinated.

MethodStudy designA time-series analysis using all-cause mortality data for Spain between 2010 and 2021, disaggregated by Spanish regions, age, and sex.

Data sourcesData come from official sources: the Spanish National Institute of Statistics and the National Epidemiology Centre (see Table A.1 in online Appendix A).

Statistical analysis- 1)

Estimation of excess deaths

We used our previously developed validated methodology for the estimation of excess deaths.5,19 Details are explained in online Appendix A. Observed weekly deaths in 2020 in each stratum (by age, sex, and region) were compared to the stratum-specific number of expected deaths. Excess death was the difference between the observed and the expected deaths. Expected deaths were estimated based on the historical trends (2015-2019) using an over-dispersed Poisson model that accounts for temporal trends, seasonal and natural variability in mortality.5,19 To compare excess death rates across regions, age and sex, excess deaths were standardised using the 2013 European Standard Population.17 The estimated number of excess deaths was compared with the reported number of COVID-19 deaths reported by each region to the National Epidemiology Centre as of 30 June 2021.

- 2)

Life expectancy and YLL in 2020 and 2021

We used the standard algorithm for calculating (abridged) life tables to calculate the LE at birth (e0) and at age 65 (e65).9 It assumes that data are available for the first year of life and for the first five years of life (see online Appendix A).

To attribute an equal loss of lifetime produced by deaths at the same age across the regions, we calculated YLL using the WHO standard life table, as is used in the Global Burden of Disease, Injuries and Risk Factor (GBD) study (see online Appendix A).

- 3)

Changes in life expectancy and YLL in 2020 and 2021

Within each region, sex and age group, we estimated the change in LE as the difference between the observed and ‘expected’ LE at birth (e0) and age 65 (e65) in 2020 and up to June 2021. We estimated the expected LE based on Lee-Carter forecasting20 using 2010-2019 data. We used a similar methodology to calculate the changes in YLL in 2020 and up to June 2021 (see online Appendix A).

All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software.

EthicsThe Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Health Carlos III issued a waiver because all data in this study were fully anonymous and aggregated, without any identifiable information.

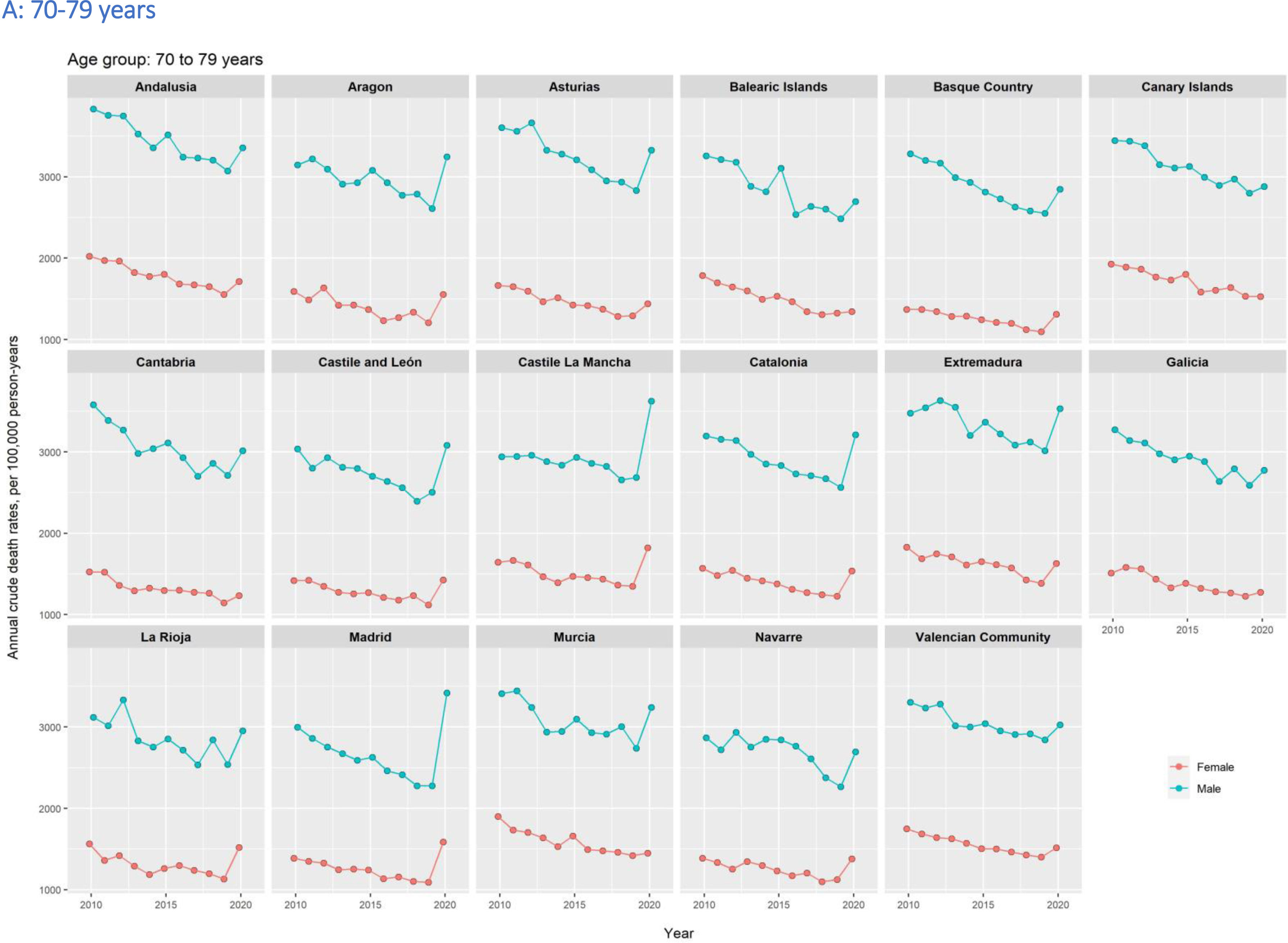

ResultsExcess deaths during 2020-2021Relative to the trend observed between 2000 and 2019, the age-specific and age-standardised death rates increased sharply in 2020, with a steeper increase in the elderly (Fig. 1). The increase was particularly higher in Madrid, Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon with a greater increase in men than in women.

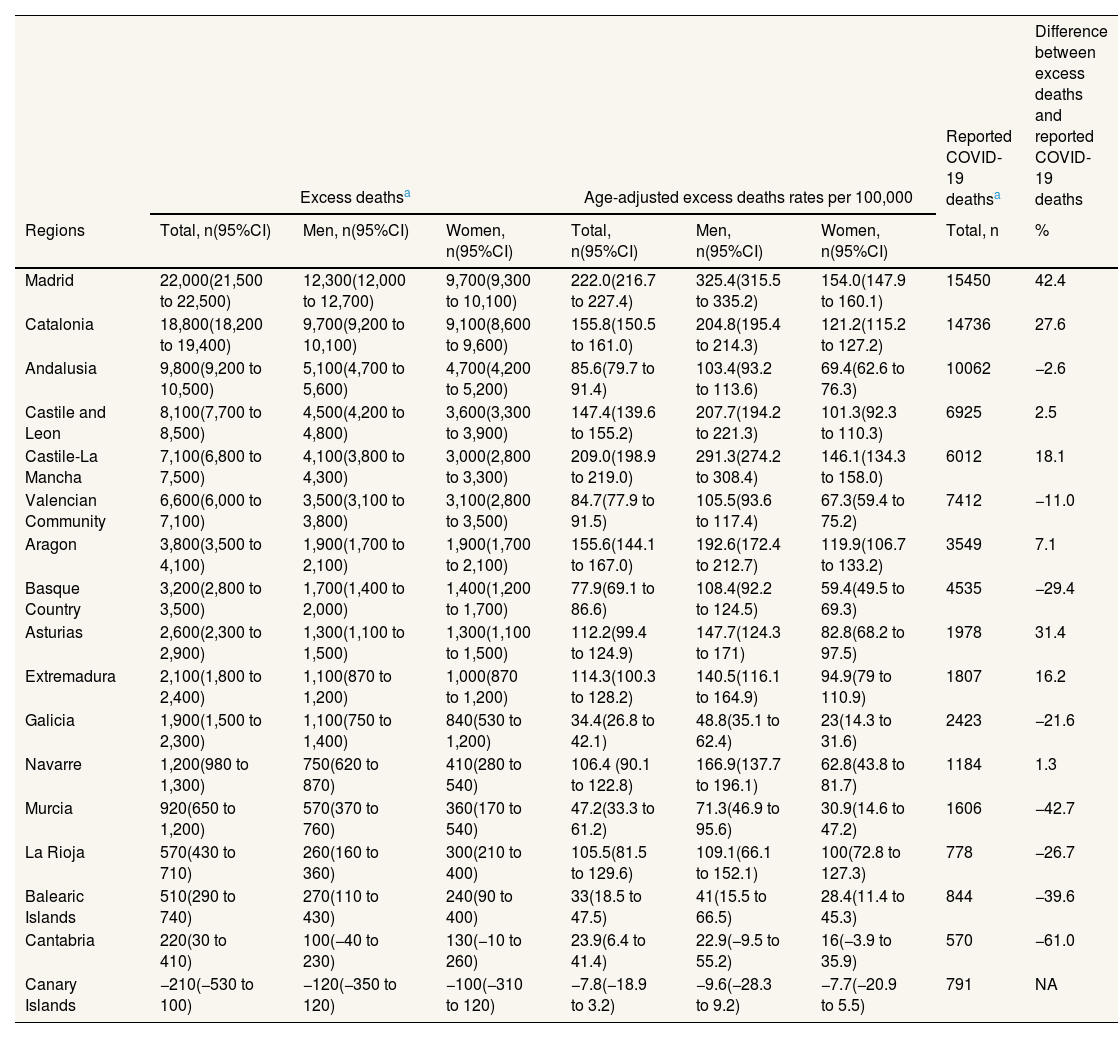

We estimated 89,200 (95% confidence interval: 87,600 to 90,800) excess deaths in Spain between January 2020 and June 2021 —in men 48,000 (46,900 to 49,200), in women 41,200 (40,000 to 42,300)—. This estimate is 10% higher than the officially reported COVID-19 deaths during the same period. We also show a wide variability in the estimated excess deaths between regions, with the highest in Madrid (22,000; 21,500 to 22,500) and the lowest in the Canary Islands (−210; −530 to 100) (Table 1). Excess deaths were higher in men than in women in most regions (see Fig. B.1 in online Appendix B).

Estimated number of excess deaths and age-standardized excess death rates from January 2020 to June 2021 in Spanish regions, by sex.

| Excess deathsa | Age-adjusted excess deaths rates per 100,000 | Reported COVID-19 deathsa | Difference between excess deaths and reported COVID-19 deaths | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions | Total, n(95%CI) | Men, n(95%CI) | Women, n(95%CI) | Total, n(95%CI) | Men, n(95%CI) | Women, n(95%CI) | Total, n | % |

| Madrid | 22,000(21,500 to 22,500) | 12,300(12,000 to 12,700) | 9,700(9,300 to 10,100) | 222.0(216.7 to 227.4) | 325.4(315.5 to 335.2) | 154.0(147.9 to 160.1) | 15450 | 42.4 |

| Catalonia | 18,800(18,200 to 19,400) | 9,700(9,200 to 10,100) | 9,100(8,600 to 9,600) | 155.8(150.5 to 161.0) | 204.8(195.4 to 214.3) | 121.2(115.2 to 127.2) | 14736 | 27.6 |

| Andalusia | 9,800(9,200 to 10,500) | 5,100(4,700 to 5,600) | 4,700(4,200 to 5,200) | 85.6(79.7 to 91.4) | 103.4(93.2 to 113.6) | 69.4(62.6 to 76.3) | 10062 | −2.6 |

| Castile and Leon | 8,100(7,700 to 8,500) | 4,500(4,200 to 4,800) | 3,600(3,300 to 3,900) | 147.4(139.6 to 155.2) | 207.7(194.2 to 221.3) | 101.3(92.3 to 110.3) | 6925 | 2.5 |

| Castile-La Mancha | 7,100(6,800 to 7,500) | 4,100(3,800 to 4,300) | 3,000(2,800 to 3,300) | 209.0(198.9 to 219.0) | 291.3(274.2 to 308.4) | 146.1(134.3 to 158.0) | 6012 | 18.1 |

| Valencian Community | 6,600(6,000 to 7,100) | 3,500(3,100 to 3,800) | 3,100(2,800 to 3,500) | 84.7(77.9 to 91.5) | 105.5(93.6 to 117.4) | 67.3(59.4 to 75.2) | 7412 | −11.0 |

| Aragon | 3,800(3,500 to 4,100) | 1,900(1,700 to 2,100) | 1,900(1,700 to 2,100) | 155.6(144.1 to 167.0) | 192.6(172.4 to 212.7) | 119.9(106.7 to 133.2) | 3549 | 7.1 |

| Basque Country | 3,200(2,800 to 3,500) | 1,700(1,400 to 2,000) | 1,400(1,200 to 1,700) | 77.9(69.1 to 86.6) | 108.4(92.2 to 124.5) | 59.4(49.5 to 69.3) | 4535 | −29.4 |

| Asturias | 2,600(2,300 to 2,900) | 1,300(1,100 to 1,500) | 1,300(1,100 to 1,500) | 112.2(99.4 to 124.9) | 147.7(124.3 to 171) | 82.8(68.2 to 97.5) | 1978 | 31.4 |

| Extremadura | 2,100(1,800 to 2,400) | 1,100(870 to 1,200) | 1,000(870 to 1,200) | 114.3(100.3 to 128.2) | 140.5(116.1 to 164.9) | 94.9(79 to 110.9) | 1807 | 16.2 |

| Galicia | 1,900(1,500 to 2,300) | 1,100(750 to 1,400) | 840(530 to 1,200) | 34.4(26.8 to 42.1) | 48.8(35.1 to 62.4) | 23(14.3 to 31.6) | 2423 | −21.6 |

| Navarre | 1,200(980 to 1,300) | 750(620 to 870) | 410(280 to 540) | 106.4 (90.1 to 122.8) | 166.9(137.7 to 196.1) | 62.8(43.8 to 81.7) | 1184 | 1.3 |

| Murcia | 920(650 to 1,200) | 570(370 to 760) | 360(170 to 540) | 47.2(33.3 to 61.2) | 71.3(46.9 to 95.6) | 30.9(14.6 to 47.2) | 1606 | −42.7 |

| La Rioja | 570(430 to 710) | 260(160 to 360) | 300(210 to 400) | 105.5(81.5 to 129.6) | 109.1(66.1 to 152.1) | 100(72.8 to 127.3) | 778 | −26.7 |

| Balearic Islands | 510(290 to 740) | 270(110 to 430) | 240(90 to 400) | 33(18.5 to 47.5) | 41(15.5 to 66.5) | 28.4(11.4 to 45.3) | 844 | −39.6 |

| Cantabria | 220(30 to 410) | 100(−40 to 230) | 130(−10 to 260) | 23.9(6.4 to 41.4) | 22.9(−9.5 to 55.2) | 16(−3.9 to 35.9) | 570 | −61.0 |

| Canary Islands | −210(−530 to 100) | −120(−350 to 120) | −100(−310 to 120) | −7.8(−18.9 to 3.2) | −9.6(−28.3 to 9.2) | −7.7(−20.9 to 5.5) | 791 | NA |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; NA: not available.

Compared to the reported number of COVID-19 deaths, the estimated number of excess deaths was 42% higher in Madrid (Table 1). The estimated excess deaths were higher than the COVID-19 deaths reported in seven other regions. However, the estimated excess deaths were lower than the COVID-19 deaths reported in nine regions (Table 1).

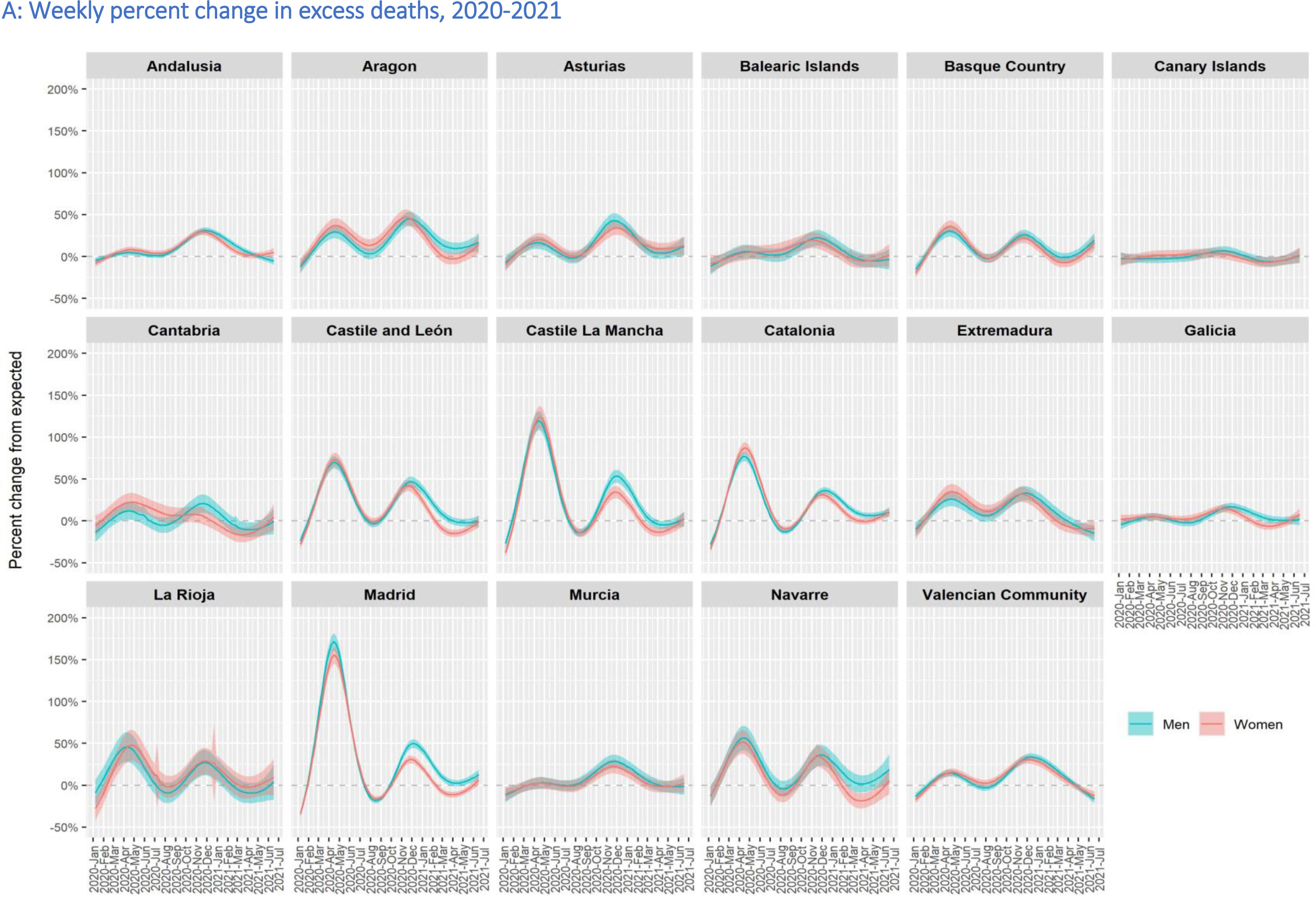

The shape of the epidemic curve of reported deaths was also highly variable across the regions and age groups. Most excess deaths occurred in the elderly population. The shape of the epidemic in most regions revealed two waves (Fig. 2 A-B). Madrid and Castile-La Mancha had more than 100% excess deaths during the first wave, and nearly 50% excess deaths in the second wave. Other regions that almost reached 50% excess deaths at the peak of the second wave were Aragon and Castile and Leon. Males had higher excess death rates than females in all age groups except among those over 90 years old (Fig. 2 A-C).

Age-standardised excess death rates (per 100,000) were highest in Madrid (222.0; 216.7 to 227.4), Castile-La Mancha (209.0; 198.9 to 219.0) and Catalonia (155.8; 150.5 to 161.0). The Balearic Islands, Galicia, Cantabria, and the Canary Islands had the lowest age-standardised excess death rates, below 35 per 100,000 (Table 1). Age-standardised excess deaths were significantly higher in men than in women in most regions, except in Murcia, the Balearic Islands, La Rioja, Cantabria and the Canary Islands, where the number of excess deaths was low and the confidence intervals wide (Table 1).

Changes in life expectancy in 2020e0 and e65 increased between 2010 and 2019 with a sharp decrease in 2020, with a steeper decline in some regions (Fig. 3 A-C). The highest reduction in e0 in men was observed in Madrid (−3.58; −3.76 to −3.40), Castile-La Mancha (−2.72; −3.34 to −1.68) and Castile and Leon (−2.13; −2.25 to −2.01). The highest reduction in e0 in women was observed in Castile-La Mancha (−2.38; −2.71 to −1.96), Madrid (−2.25; −2.66 to −1.82) and Catalonia (−2.06; −2.28 to −1.85). The e0 observed in 2020 for males was at the level of 2006 for Castile-La Mancha and 2008 for Madrid; for females, it was at the level of 2004 and 2006 for these regions, respectively.

The highest reduction in e65 in men was observed in Madrid (−3.23; −3.41 to −3.06), Castile-La Mancha (−2.75; −2.96 to −2.55) and Castile and Leon (−1.84; −1.97 to −1.73). The highest reduction in e65 in women was observed in Madrid (−2.07; −2.48 to −1.69), Castile-La Mancha (−2.03; −2.4 to −1.66) and Catalonia (−1.78; −2 to −1.57). The e65 observed in 2020 in men in Madrid, Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon was at the level of 2004, 2000 and 2004, respectively; in women, it was at the level of 2006, 2004 and 2008 for these regions, respectively.

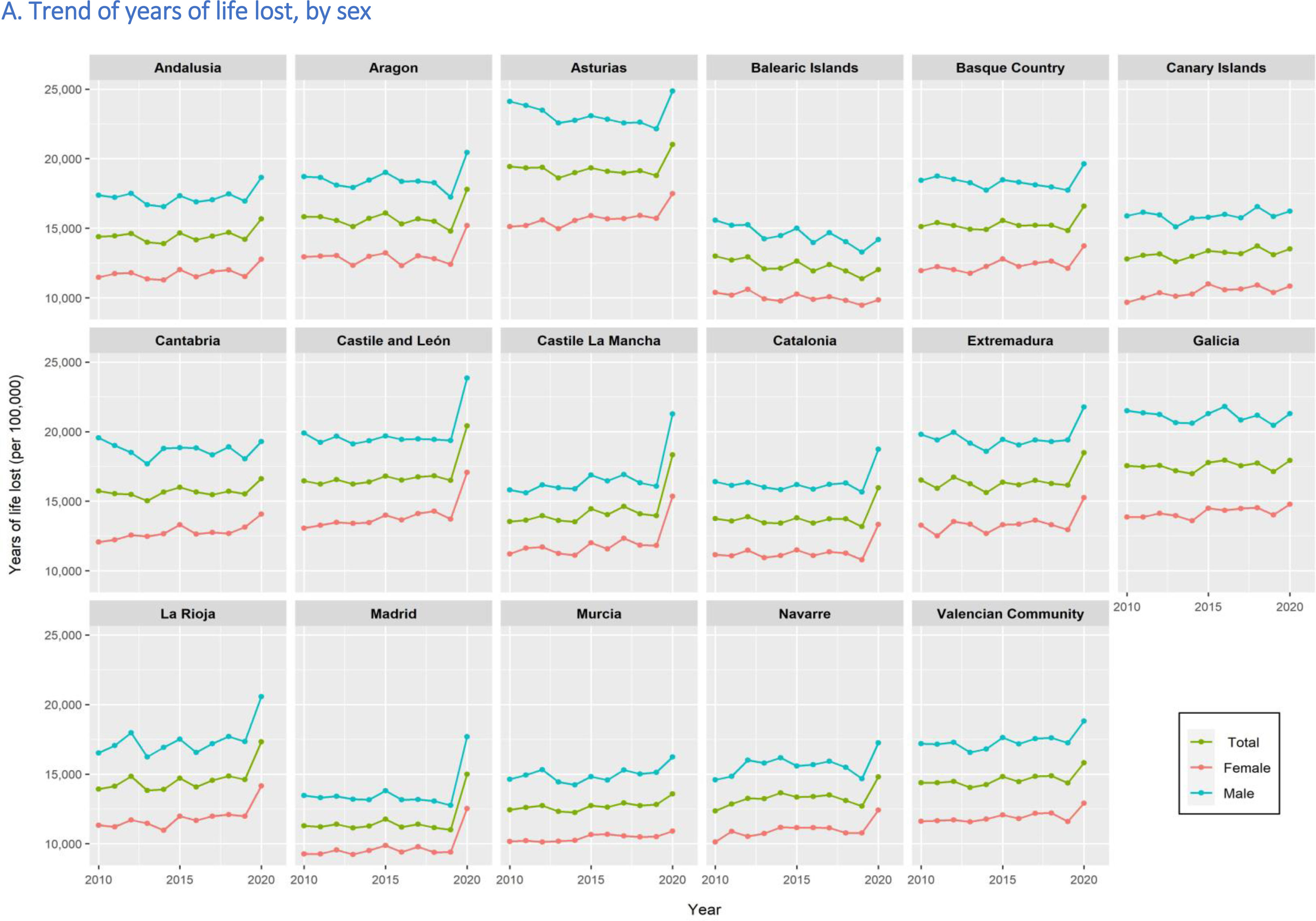

Excess in YLL in 2020YLL decreased from 2010 to 2019 with a sharp increase in 2020 in most regions, especially in men and the elderly (Fig. 4). Excess YLL (per 100,000) in men was highest in Castile-La Mancha (5370; 3190 to 7570), Madrid (5240; 4510 to 5990) and Castile and Leon (4360; 3670 to 5050). Excess YLL (per 100,000) in women was highest in Madrid (3600; 1980 to 5210), Castile-La Mancha (2760; 1960 to 3560) and Catalonia (2760; 1960 to 3560).

Provisional changes in life expectancy in 2021Based on data up to the 24th week in 2021, e0 and e65 continued to fall in most regions (Fig. 3 D). Highest reduction in e0 in 2021 for men was observed in Madrid (−2.09; −2.37 to −1.84), Valencian Community (−2.04; −2.36 to −1.73) and Aragon (−2.03; −2.27 to −1.79). Highest reduction in e0 in 2021 for women was observed in Valencia Community (−1.63; −1.97 to −1.3), Andalusia (−1.43; −1.77 to −1.1) and Catalonia (−1.37; −1.69 to −1.06). These regions also had the highest reduction in e65 for both men and women.

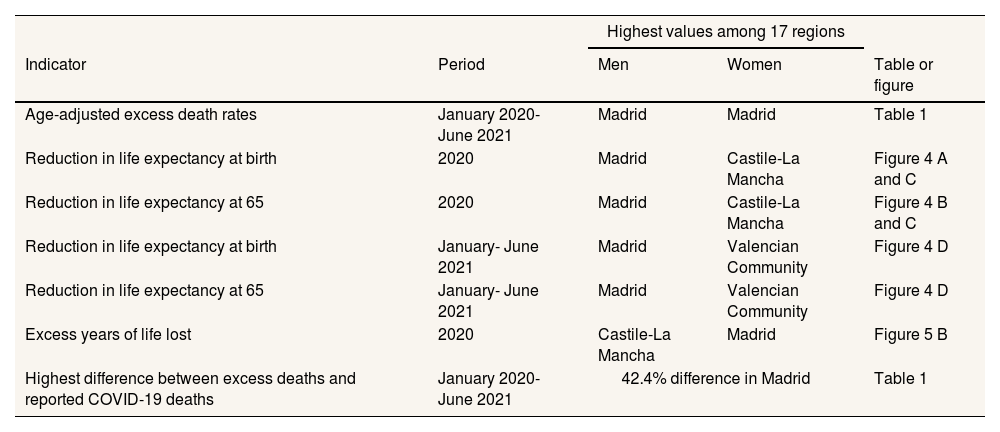

DiscussionWe showed that there were substantial excess deaths in all Spanish regions except the Canary Islands and Cantabria. Excess deaths were higher in men than in women in most regions. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain why men perform worse than women, including genetics, sex hormones, and lifestyle behaviours.7,21 Most excess deaths occurred in Madrid, Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon. The highest difference was observed in Madrid. The highest reduction in e0 in men was also observed in Madrid. The observed reduction in e0 and e65 in 2020 delayed the LE as far as 15 years in some regions. The excess in YLL was highest in men in Castile-La Mancha and women in Madrid. In eight regions, the number of excess deaths was higher than the number of COVID-19 deaths reported. The estimated excess deaths were 42% higher than the officially reported COVID-19 deaths in Madrid, suggesting the poorest quality of COVID-19 death reporting in the Madrid region. Table 2 summarises these results.

Regions of Spain with the highest impact of COVID-19 as measured by excess death rates, reductions in life expectancy and excess years of life lost, and difference between excess deaths and deaths reported by COVID-19.

| Highest values among 17 regions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator | Period | Men | Women | Table or figure |

| Age-adjusted excess death rates | January 2020-June 2021 | Madrid | Madrid | Table 1 |

| Reduction in life expectancy at birth | 2020 | Madrid | Castile-La Mancha | Figure 4 A and C |

| Reduction in life expectancy at 65 | 2020 | Madrid | Castile-La Mancha | Figure 4 B and C |

| Reduction in life expectancy at birth | January- June 2021 | Madrid | Valencian Community | Figure 4 D |

| Reduction in life expectancy at 65 | January- June 2021 | Madrid | Valencian Community | Figure 4 D |

| Excess years of life lost | 2020 | Castile-La Mancha | Madrid | Figure 5 B |

| Highest difference between excess deaths and reported COVID-19 deaths | January 2020-June 2021 | 42.4% difference in Madrid | Table 1 | |

A previous study used the 75,073 excess deaths reported by the National Institute of Statistics between January 2020 and February 2021 and compared the difference between observed and expected deaths, assuming that these excess deaths were distributed proportionally to the population size of each region. Madrid and its two nearby regions, Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon, had the highest excess mortality (48%, 74% and 80%, respectively) and the Canary Islands and eight other regions had fewer deaths than expected.18 García-García et al. reported excess deaths in Spain between 3 March and 29 November 2020 using the Mortality Monitoring (MoMo) surveillance system, designed to assess peaks when observed deaths from any cause are higher than those expected —as the average of the last 10 years— for at least two consecutive days.22 Crude excess death rates per 100,000 population were higher in Castile-La Mancha (347), Madrid (261) and Castile and Leon (244), whereas the Canary Islands had the lowest rate (43). Moreover, the European Committee on the Regions in a report of excess deaths in 2020 compared to the average number of deaths between 2016 and 2019, showed that Madrid was the most affected region in Europe, 44%, followed by Lombardia, Italy, 39%, and Castile-La Mancha, 34%.3

We previously reported a national decline in LE of −1.35 (−1.72 to −0.99) years in Spain in 2020.9 However, this analysis shows large variations in LE loss across regions. Using partial data up to July 5, 2020, a previous study reported a reduction in LE of 2.8 years in the city of Madrid.11 This study compared provisional 2020 estimates with 2019 estimates, which may have contributed to an underestimation of the effect on LE in all regions.9 Comparing the 2020 estimates with 2019 estimates or with an average of recent years may lead to incorrect conclusions because it ignores recent trends in mortality.9 The reduction in LE at age 65 was particularly large in central Spain, consistent with the high COVID-19 mortality in long-term care facilities in these regions.23 In 2020, premature mortality in our study was 52 YLL/1000 in men and 36 YLL/1000 women in Madrid, higher than recently reported,16 perhaps due to differences in the statistical methods used.

Reported COVID-19 deaths were lower than the number of excess deaths in eight of the seventeen regions, suggesting possible under-reporting of the COVID-19 deaths. In contrast, the number of reported COVID-19 deaths was larger than the number of excess deaths in the remaining nine regions. For instance, in the Basque Country, the model estimated an excess of 3200, while 4535 confirmed COVID-19 deaths were reported. The difference, 1335, could have been the deaths that would have happened had the COVID-19 pandemic not occurred. This ‘avoided mortality’ could come from healthy changes in behaviour and environment,24 a less severe influenza season in 2020-2021 and compliance with public health measures that could reduce risk. The regions where reported COVID-19 deaths were higher than the estimated excess deaths were the Canary Islands, the Valencian Community, the Basque Country, Galicia, Murcia, La Rioja, the Balearic Islands and Cantabria and, to a lesser extent, Andalusia. In most of these regions, the epidemic in spring 2020 was less severe and healthcare services did not collapse as was the case for regions with a strong epidemic in spring 2020, especially Madrid and Castile-La Mancha. In Catalonia, diagnoses of acute respiratory infections in primary care helped to predict the course of the epidemic and prevent the collapse of intensive care units.25 In Almeria, the coordination of public health, primary and specialized care to manage COVID-19 outbreaks resulted in low mortality among long-term care residents.26

In our results, Madrid stood out as the region with the highest pandemic-associated mortality. The variability in excess deaths found in the regions of Spain during the first and second waves is consistent with the variability found in the first national study of SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence (ENE-COVID Study) conducted in the community population.27 According to this survey, Madrid, the neighbouring five provinces in Castile-La Mancha and two close provinces of Castile and Leon had the highest prevalence of IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2. To some extent, the excess deaths and high seroprevalence of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in the provinces close to Madrid could have been related to their high population mobility.

Public health interventions and the organisation of health and social services to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic also varied substantially between regions.28 During the second half of 2020 and the first half of 2021, each region exerted its own prevention and control measures with large regional variations in the periods and types of lockdowns and additional interventions. The Madrid government's health policy interventions were repeatedly questioned by public health experts in scientific journals and in the media.29 Some illustrations follow:

When the pandemic was declared, the Madrid government established a disability-based triage for nursing home residents, prohibiting referral to public hospitals for nursing home residents with severe disability or cognitive impairment.30 During March-April 2020, 20% of nursing home residents died.31 The region of Madrid has 13.5% of Spain's nursing home residents, so 4,074 COVID-19 deaths (13.5% of the 30,117 total deaths in nursing homes in Spain) would have been expected. However, COVID-19 deaths registered in nursing homes in Madrid were 6,228, an excess of 52.9% over the expected number. Patients at nursing homes were first excluded from the care mechanisms available under the health emergency and did not receive adequate care.32

During the autumn of 2020, the governments of Madrid's neighbouring regions (Castile and Leon and Castile-La Mancha) closed their borders. On 28 October, the government of Madrid refused to join. More than 160,000 people were travelling daily to work in Madrid from other provinces, with about 120,000 coming from four neighbouring provinces in Castile-La Mancha and Castile and Leon. Our findings confirm previous research showing that Madrid was an epidemic epicentre for COVID-19 transmission. Furthermore, a unique system of perimeter confinements by basic health zones had no significant effects on COVID-19 incidence.33

During the winter of 2020/2021, the city of Madrid became an open leisure destination for Europeans. In Madrid, hotels, bars and restaurants remained open despite evidence of their important role in community transmission.34

The Canary Islands had the lowest excess mortality in all age and sex groups, which could be attributed to an effective surveillance, prevention and control strategy during the early phase of the pandemic and the implementation of evidence-based interventions.35 The Islands reported its first case of COVID-19, a German tourist in La Gomera, on 31 January 2020. The local authority responded quickly with isolation of the detected case and contact tracing, thus preventing an early spread of the pandemic. Following the diagnosis of the second case, public health authorities in the Canary Islands applied strict quarantine measures to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. In Madrid, the region with the highest excess deaths, the first case was diagnosed on 25 February 2020, although a retrospective investigation suggested that Madrid had probably diagnosed the first COVID-19 case in Spain in early January 2020.29 By the time public health authorities implemented measures in Madrid, in early March 2020, widespread community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was already happening (see online Appendix C).

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive analysis of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Spanish regions using three important and complementary parameters of excess and premature mortality. We are not aware of any previous studies that have estimated the effects of the pandemic on LE and YLL in Spanish regions. The analyses presented here are based on newly developed methods that allow us to examine excess deaths and premature mortality by age group and sex. The analyses also consider period and seasonal changes that are sensitive to environmental and social changes. The accuracy of the number of deaths and populations by region, age group and sex provided by the National Institute of Statistics is robust and reliable, overcoming variations in the quality of death reporting by COVID-19 between regions. Our study provides new evidence on the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on excess and premature mortality, highlighting the importance of the availability of age- and sex-disaggregated data for more nuanced analysis. We did not cover the post-vaccination period and we did not analyse the impact of COVID-19 on cause-of-death data.

Conclusion and recommendationWe found large regional inequalities in excess deaths, life expectancy loss at birth and age 65, and years of life lost during 2020 and the first half of 2021. Madrid stood out as the region with the highest mortality impact from the COVID-19 pandemic, while the Canary Islands had the best indicators. Investigating the root causes of these regional inequalities might inform future pandemic policy in Spain and elsewhere. A concerted effort to share knowledge on pandemic preparedness, challenges, and opportunities in public health policy implementations at local levels, and population participation and resilience can help improve our shared decision-making.

Availability of databases and material for replicationOn request and at https://repisalud.isciii.es/

Spain was one of the most heavily affected European countries by the COVID-19 pandemic and Madrid was the European region with the highest excess deaths in 2020. A recent independent evaluation analysed the strengths and weaknesses of the management of the pandemic by the National Health System and highlighted the country's lack of preparedness.

What does this study add to the literature?We found large regional inequalities in excess deaths, life expectancy loss at birth and at age 65, and years of life lost. Madrid was the region with the highest impact and the Canary Islands had the lowest impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

What are the implications of the results?Our findings call for an evaluation of the root causes behind regional inequalities: differences in timely and evidence-based public health policy interventions, organisation of health resources and public health interventions.

Vanessa Santos.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsM.V. Zunzunegui, F.J. García López, M.A.R.-B. and N. Islam conceptualised the study with the input from all the coauthors. N. Islam and D.A. Jdanov conducted the statistical analysis. N. Islam wrote the first draft. All the authors provided critical scholarly feedback on the manuscript. All the co-authors approved of the final version of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestN. Islam and S. Lewington are the members of the WHO-UN DESA Technical Advisory Group on Covid-19 mortality assessment. S. Lewington reports grants from the Medical Research Council (MRC), and HDR UK (HDRUK2023.0028) funded by the MRC, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, Department of Health and Social Care (England), Chief Scientist Office of the Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, Health and Social Care Research and Development Division (Welsh Government), Public Health Agency (Northern Ireland), British Heart Foundation (BHF) and Cancer Research UK; and research funding from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Foundation (with support from Amgen) and from the World Health Organization during the conduct of the study, all outside the submitted work. The Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit (CTSU) receives research grants from industry that are governed by University of Oxford contracts that protect its independence and has a staff policy of not taking personal payments from industry; further details can be found at [https://www.ndph.ox.ac.uk/files/about/ndph-independence-of-research-policy-jun-20.pdf]. M. White reports research funding from the Economic & Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, National Institute for Health Research and Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council unrelated to this study. K. Khunti is a Member of the UK Scientific Advisory Group for Emergency (SAGE), and Independent SAGE. Other authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest.