The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoOne of the indicators in measuring the nutritional status of a particular community is the nutritional status of pregnant women. A nutritional deficiency occurs if nutritional input for pregnant women from food is not balanced with their body's needs. Several determinants are related to nutritional status. This study aimed to determine the relationship between socioeconomic and nutritional status of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

MethodsThis research was a quantitative observational study with a cross-sectional study approach. Sampling was done by random sampling technique, which obtained 85 pregnant women. Data collection was carried out using a questionnaire.

ResultsBased on the Chi-Square test, p-value=0.001, which means that difference between socioeconomic status and nutritional status in pregnant women was significant (p<0.05). Variable of parity factor that was at risk and no risk in pregnant women showed p-value=0.030 and p-value=0.048. Additionally, the variable of pregnancy gap factor that was at risk and no risk in pregnant women showed p=0.070 and p=0.159. In addition, infectious disease factor that was at risk and no risk in pregnant women showed p-value=0.017 and p-value=0.027. Last but not least, implementation of ANC variable that was in line with standards and not in line with standards in pregnant women showed p-value=0.019 and p=0.043.

ConclusionBased on the Chi-Square test calculation, p-value=0.001, which indicates a significant value between socioeconomic status and nutritional status in pregnant women (p<0.05).

One of the indicators in measuring the nutritional status of a particular community is the nutritional status of pregnant women. A nutritional deficiency occurs if nutritional input for pregnant women from food is not balanced with their body's needs. Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) is one of the important indicators in determining the degree of public health. Based on data from the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012, MMR in developed countries ranged from 5 to 10 per 100,000 live births, while MMR in developing countries ranged from 750 to 1000 per 100,000 live births.1

Furthermore, there are around 160 million women around the world getting pregnant every year. Most of these pregnancies are safe. However, about 15% of pregnancies suffer from severe complications, with one third being life-threatening complications of mothers. Globally, 80% of maternal deaths are classified as direct maternal deaths. Causes patterns of direct maternal deaths are mostly similar, including bleeding (25% usually postpartum bleeding), sepsis (15%), hypertension in pregnancy (12%), dystocia (8%), malnutrition (13%), and other causes (8%).2

Additionally, factors causing malnutrition can be seen from direct, indirect, main causes, and root causes of the problem. Direct causes include unbalanced food and infections, while indirect causes include food security in family, child care patterns, health services and environmental health.3

In Indonesia, a nutritional problem that is happening is the problem of multiple nutrition, namely malnutrition and overnutrition. Malnutrition is usually caused by poverty, lack of food availability, poor environmental sanitation, lack of community knowledge about nutrition, and poor nutrition areas. On the other hand, overnutrition is usually caused by economic progress in certain strata of society which is not balanced by an increase in nutritional knowledge.4

Some evidence in developing countries shows that pregnant women with malnutrition based on Body Mass Index (BMI)<18.5 increase risk of death in line with increased risk of illness. Importantly, pregnant women based on socioeconomic reasons are one of the vulnerable groups of malnutrition who are most at risk for malnutrition, perinatal and neonatal mortality, high risk of giving birth to babies with Low Birth Weight (LBW), stillbirth babies and miscarriages.5

Some of the causes that influence the occurrence of malnutrition are lack of food intake and infectious diseases. Pregnant women who suffer from illness will experience malnutrition despite getting adequate food intake. Pregnant women with less food intake tend to have a weak immune system and are susceptible to disease. Other factors that influence the occurrence of malnutrition in pregnant women are low levels of education, maternal knowledge about malnutrition, inadequate family income, maternal age less than 20 years or more than 35 years, and birth spacing that is too close.6

According to previous research, it is stated that pregnant women with low education have a tendency to experience energy deficiency 2.5 times higher than pregnant women with high education. Besides the level of education, employment and income are also some pictures of the economic status of a family. Employment has an important role in providing an effect on living standards. It is in line with this research that pregnant women who do not work have a risk of 9286 times greater to experience less nutrition than pregnant women who work.7

In fact, work or employment affects income that will be used to meet the needs of a family, including nutrition and health. Research by Hamzah (2017) in Aceh pointed out that pregnant women who have income below Regional Minimum Wage (RMW) are more at risk of experiencing malnutrition 3.100 times greater than pregnant women who have income above RMW.8

Pregnancy gap or birth spacing also affects the nutritional status of pregnant women, which increases the number of children with close proximity increases the state of malnutrition. A number of children reflect many factors that characterize the reproductive life of the mother, such as workload for child care, breastfeeding, and birth intervals. A mother with three children under five years tends to have a greater workload and does not have time to recover physically due to the close distance of pregnancy and breastfeeding. A history of maternal reproduction has a significant impact on nutritional status and has been identified as a cause of malnutrition in Sub-Saharan region.9,10

Besides birth spacing, parity is another reason that affects the nutritional status of the mother. A research proved that there is a relationship between parity and nutritional status; the higher the parity of mother, the greater the risk of experiencing malnutrition. Mothers who frequently get pregnant and give birth automatically have many children, by which needs of life increase, especially in terms of nutritional needs.11,12

A prenatal screening test is an effort to reduce maternal mortality—the higher the coverage of antenatal care, the better the process of pregnancy and childbirth. Poor antenatal care examinations are 2.7 times more at risk of having less chronic energy than mothers who receive good antenatal care examinations. It is in line with research conducted by Mardiatun et al. (2016) who found that antenatal care is 1.793 times significant for the risk of malnutrition.13

Based on the aforementioned description, the cause of malnutrition in pregnant women is not only a single factor. Therefore, researchers believe that it is important to conduct research on “The Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Temporary Shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi”.

Materials and methodsThis research was a cross-sectional study, in which observation and measurement of independent and dependent variables were conducted at the same time. The dependent variable in this study was the nutritional status of pregnant women, while independent variable of this study was variable influencing changes in the emergence of dependent variable which included socioeconomic relationships based on age, education, and income. Sampling was done by random sampling technique, which obtained 85 pregnant women. Data were collected through interviews based on a questionnaire and then processed with multiple logistic regression tests using SPSS version 22 application.

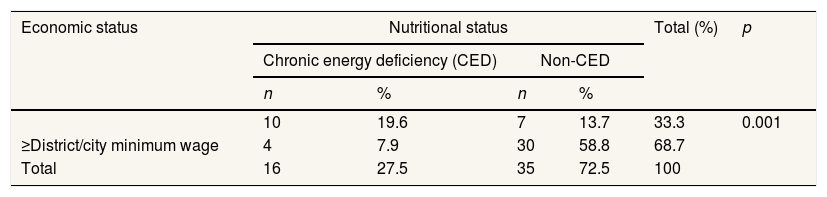

ResultsThe following are results in the variable of Relationship between Economic Status and Nutritional Status of Pregnant Women in Temporary Shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

Table 1 shows that there are more pregnant women withp<0.05).

Relationship between economic status and nutritional status of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

| Economic status | Nutritional status | Total (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic energy deficiency (CED) | Non-CED | |||||

| n | % | n | % | |||

| 10 | 19.6 | 7 | 13.7 | 33.3 | 0.001 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 4 | 7.9 | 30 | 58.8 | 68.7 | |

| Total | 16 | 27.5 | 35 | 72.5 | 100 | |

Source: Primary Data, 2020.

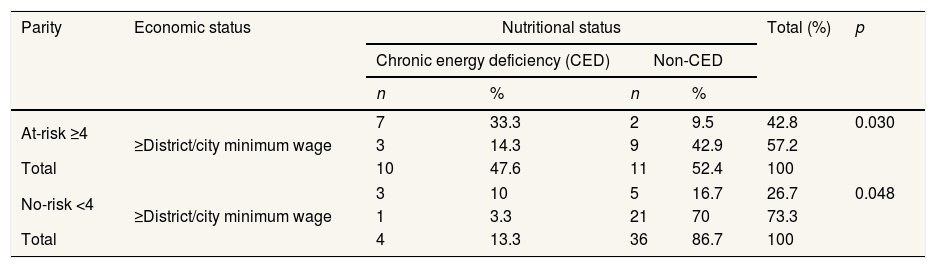

Table 2 shows the results of a bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on risk parity ≥4. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.030 <0.05, which means that there is a relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on risk parity ≥four pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

Relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on parity of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

| Parity | Economic status | Nutritional status | Total (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic energy deficiency (CED) | Non-CED | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| At-risk ≥4 | 7 | 33.3 | 2 | 9.5 | 42.8 | 0.030 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 3 | 14.3 | 9 | 42.9 | 57.2 | ||

| Total | 10 | 47.6 | 11 | 52.4 | 100 | ||

| No-risk <4 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 16.7 | 26.7 | 0.048 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 1 | 3.3 | 21 | 70 | 73.3 | ||

| Total | 4 | 13.3 | 36 | 86.7 | 100 | ||

Source: Primary Data, 2020.

Table 2 shows the results of a Bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on risk parity <4. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.048 <0.05, indicating that there is a relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on no-risk parity <4 pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

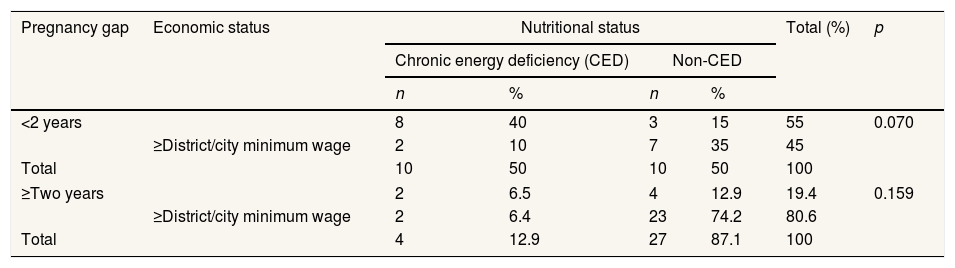

Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on pregnancy gap that is at risk <2 years. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.070>0.05, which indicates that there is no relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on pregnancy gap that is not at risk <2 years pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

Relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on pregnancy gap for pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

| Pregnancy gap | Economic status | Nutritional status | Total (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic energy deficiency (CED) | Non-CED | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| <2 years | 8 | 40 | 3 | 15 | 55 | 0.070 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 2 | 10 | 7 | 35 | 45 | ||

| Total | 10 | 50 | 10 | 50 | 100 | ||

| ≥Two years | 2 | 6.5 | 4 | 12.9 | 19.4 | 0.159 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 2 | 6.4 | 23 | 74.2 | 80.6 | ||

| Total | 4 | 12.9 | 27 | 87.1 | 100 | ||

Source: Primary Data, 2020.

Furthermore, Table 3 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on pregnancy gap at risk ≥two years. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.159>0.05, which indicates that there is no relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on pregnancy gap at risk ≥two years of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

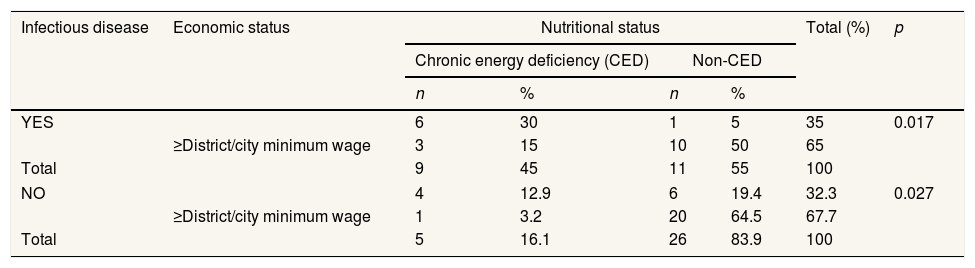

Table 4 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on infectious disease at risk “Yes”. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.017<0.05, which indicates that there is a relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on infectious disease at risk “YES” in pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

Relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on infectious disease at risk “YES” in pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

| Infectious disease | Economic status | Nutritional status | Total (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic energy deficiency (CED) | Non-CED | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| YES | 6 | 30 | 1 | 5 | 35 | 0.017 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 3 | 15 | 10 | 50 | 65 | ||

| Total | 9 | 45 | 11 | 55 | 100 | ||

| NO | 4 | 12.9 | 6 | 19.4 | 32.3 | 0.027 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 1 | 3.2 | 20 | 64.5 | 67.7 | ||

| Total | 5 | 16.1 | 26 | 83.9 | 100 | ||

Source: Primary Data, 2020.

Table 4 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on an infectious disease that is not at risk “No”. There are more respondents with economic status p-value is 0.027<0.05 which indicates that there is a relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on an infectious disease that is not at risk “No” in pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu.

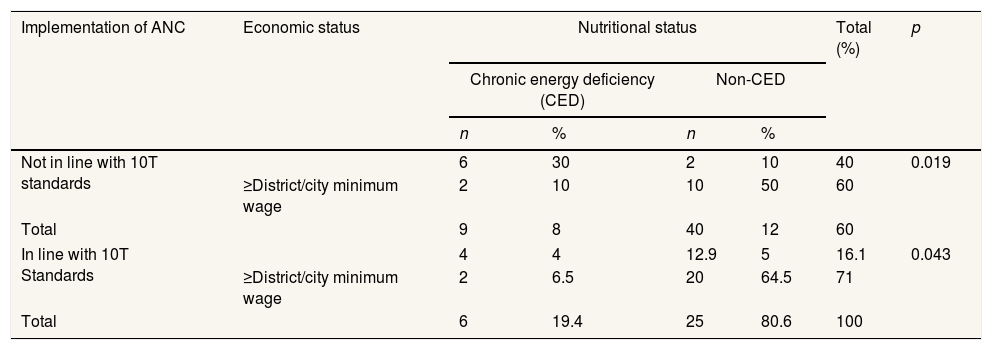

Table 5 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on the implementation of ANC that is not in line with 10T standards. There are more respondents with economic status

Relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on the implementation of antenatal care (ANC) in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi 2020.

| Implementation of ANC | Economic status | Nutritional status | Total (%) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic energy deficiency (CED) | Non-CED | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Not in line with 10T standards | 6 | 30 | 2 | 10 | 40 | 0.019 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 2 | 10 | 10 | 50 | 60 | ||

| Total | 9 | 8 | 40 | 12 | 60 | ||

| In line with 10T Standards | 4 | 4 | 12.9 | 5 | 16.1 | 0.043 | |

| ≥District/city minimum wage | 2 | 6.5 | 20 | 64.5 | 71 | ||

| Total | 6 | 19.4 | 25 | 80.6 | 100 | ||

Source: Primary Data, 2020.

Table 5 shows the results of the bivariate analysis of the relationship between economic status and nutritional status based on the implementation of ANC based on 10T standards. There are more respondents with economic status

DiscussionResults of this study indicated a relationship between economic status and nutritional status of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi. Chi-Square test results showed a significant relationship between economic status and nutritional status at α 0.05 with p 0.027. Family ability to buy food depends on family income. Family with limited income is likely to not meet nutritional needs in their bodies. Accurate data is required in order to handle and reduce the high-risk associated with pregnancy properly. When complications are not early detected, they continually grow into serious complexity, thereby threatening both mother and fetus. This leads to an increase in morbidity and mortality rates.14

There were 60%–80% of low-income household income spent on food. Moreover, 70–80% of energy was filled with carbohydrates (rice and substitutes), and only 20 per cent was filled with other energy sources such as fat and protein. Results of this research are in line with research which revealed that there is a relationship between economic status and incidence of Chronic Energy Deficiency (CED) in pregnant women in Ngambon sub-district, Bojonegoro.

However, results of this research are not in line with a research by Hamzah (2017) in Aceh that Pregnant women who have an income below Provincial Minimum Wage (PMW) are more at risk of experiencing Chronic Energy Deficiency 3.155 times than pregnant women who have an income above PMW.8 Most importantly, income obtained by a family is crucial in meeting primary needs that have an impact on family's health status. It is in line with research which concluded that pregnant women with low monthly household income are 8.72 times more at risk of developing CED. A similar point was found that there is a significant relationship between monthly family income and the incidence of CED in pregnant women.15

ConclusionThere is a significant relationship between economic status and nutritional status of pregnant women in temporary shelter, Talise, Palu, Central Sulawesi.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors would like to thank for Dean and the all vice-dean the Faculty of Public Health at Hasanuddin University for the research funding.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.