The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoThis study aimed to analyze the influence of macronutrient intake, stress, and prostaglandin levels (pgf2α) on adolescent dysmenorrhea incidence.

MethodThis type of study is observational analytic with a cohort study draft done in January–March 2020 at High junior school 21 Makassar. Respondents in this study were grade X and XI students divided into 64 teenagers who had dysmenorrhea and 64 adolescents who did not experience Dysmenrhea. The criteria of the respondent in this study were the reproductive age, already experiencing menstruation, knowing the time and date of menstruation, menstrual cycles were regular, and willing to be respondents. The study used Menstrual Symptoms Questionnaire (MSQ) and used an ultrasonography (ultrasound) examination to perform the sample cervical. Food recall 24 hours to assess the intake of macronutrients, Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS 42) to measure stress levels, and an examination of urine prostaglandin levels using the method Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). Urine intake is carried out on the second day as much as 2–5cc. Data were analyzed by the Chi-square test and logistics regression backward.

ResultA multivariate analysis showed a variable that strongly affects dysmenorrhea is stress with the value p=0.000 and the level of prostaglandins with p-value=0.003 compared to other variables.

ConclusionStress and prostaglandin levels significantly affect the occurrence of dysmenorrhea in adolescents.

During menstruation, women experience a variety of disorders that can cause physical and disturbing activities. One inconvenience is dysmenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea is a public health problem that means menstruation that nyeri.1–4

Dysmenorrhea is a health problem that has a negative impact on physical and emotional health and most causes absence in school that affects academic presentation. Dysmenorrhea in women can affect students’ academic abilities, school absences, and loss of daily work.5–7 A dysmenorrhea incidence rate in Indonesia amounted to 107,673 people, consisting of 59,671 people experiencing primary dysmenorrhea (54.89%) The soul and 9496 people experience secondary dysmenorrhea (9.36%) Jiwa.8,9

Balanced dietary nutritional intake (e.g., due to protein or high fat, or low fiber intake) is associated with a greater risk of obesity in children and adolescents than adults. Therefore, it is not only the macro intake needed for health, but the quality of the diet also affects examples of fats and carbohydrates (complex and straightforward fibers and carbohydrates) and proteins (animals and plants). Nutritional Status of overweight and obesity is also a risk factor of dysmenorrhea.10,11

The pain that accompanies uterine contractions can affect functional mechanisms, and one of the causes of dysmenorrhea is psychic, and one of those psychic factors is the stress that causes a physiological stress response. The stress response includes activating the sympathetic nervous system and the release of various hormones and peptides. More and more formed prostaglandins and vasopressin cause the uterine contraction of the uterus to clamp the ends of the nerve fibers; further, the formation is transmitted through sympathetic nerve fibers.12–14

MethodsResearch sitesThe study was conducted in January–March 2020 and has received a recommendation of ethical approval with the protocol number UH19110996. Research conducted at High junior school 21 Makassar and laboratory of Microbiology of the Hasanuddin University of Makassar.

Data types and sourcesThe Data collected from the samples are age, menstrual cycle, prolonged menstruation, macronutrient intake, stress level, urine prostaglandin levels, and medical diagnosis. Data were taken from the students who are dysmenorrhea and not dysmenorrhea.

Data collection techniqueData related to respondents were gathered through questionnaires, live interviews, and the respondent's USG examination and urine sampling. The collected samples are then stored in the refrigerator at a temperature of −20°C. After the samples were fulfilled, the examination of prostaglandin (pgf2α) used the Kit Elisa, Bioassay Technology Laboratory at the Hasanuddin University of Makassar Hospital laboratory.

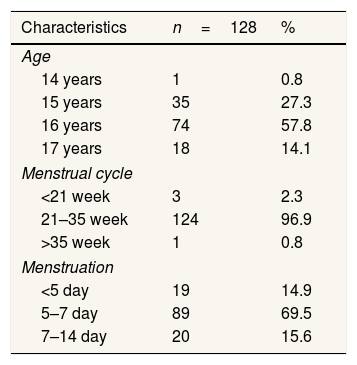

ResultsThe majority of respondents were 16 years old with menstrual cycles of 21–35 weeks and menstrual periods of 5–7 days (Table 1).

Characteristics of the respondents group of cases and controls on high junior school 21 Makassar.

| Characteristics | n=128 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 14 years | 1 | 0.8 |

| 15 years | 35 | 27.3 |

| 16 years | 74 | 57.8 |

| 17 years | 18 | 14.1 |

| Menstrual cycle | ||

| <21 week | 3 | 2.3 |

| 21–35 week | 124 | 96.9 |

| >35 week | 1 | 0.8 |

| Menstruation | ||

| <5 day | 19 | 14.9 |

| 5–7 day | 89 | 69.5 |

| 7–14 day | 20 | 15.6 |

Source: Primary Data year 2020.

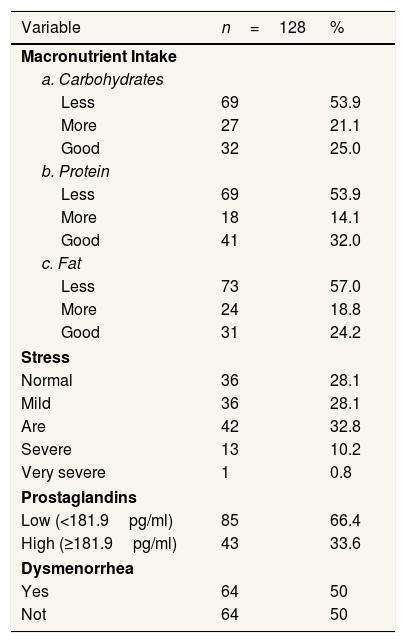

Most respondents have less intake of macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein, fat). Most respondents have moderate stress levels, and respondents have the lowest levels of prostaglandins. The number of respondents who experienced dysmenorrhea was 64 people and not dysmenorrhea 64 people (Table 2).

Variable case group and control study on high junior school 21 Makassar.

| Variable | n=128 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Macronutrient Intake | ||

| a. Carbohydrates | ||

| Less | 69 | 53.9 |

| More | 27 | 21.1 |

| Good | 32 | 25.0 |

| b. Protein | ||

| Less | 69 | 53.9 |

| More | 18 | 14.1 |

| Good | 41 | 32.0 |

| c. Fat | ||

| Less | 73 | 57.0 |

| More | 24 | 18.8 |

| Good | 31 | 24.2 |

| Stress | ||

| Normal | 36 | 28.1 |

| Mild | 36 | 28.1 |

| Are | 42 | 32.8 |

| Severe | 13 | 10.2 |

| Very severe | 1 | 0.8 |

| Prostaglandins | ||

| Low (<181.9pg/ml) | 85 | 66.4 |

| High (≥181.9pg/ml) | 43 | 33.6 |

| Dysmenorrhea | ||

| Yes | 64 | 50 |

| Not | 64 | 50 |

Source: Primary Data year 2020.

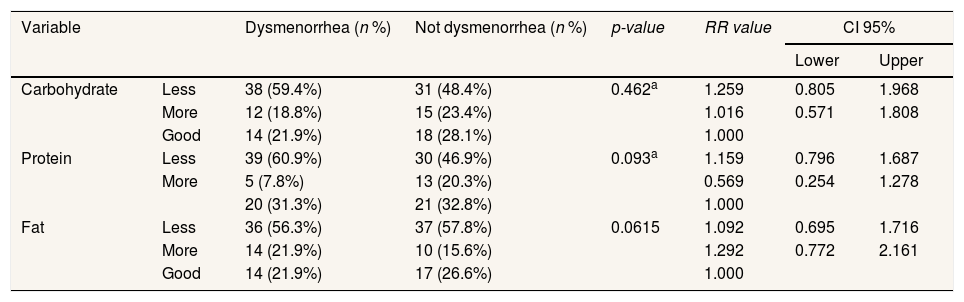

Respondents who experience dysmenorrhea and not dysmenorrhea have less macronutrient intake (carbohydrate, fat, protein), i.e., the p-value is >0.05 (Table 3).

Influence of macronutrient intake with dysmenore incidence.

| Variable | Dysmenorrhea (n %) | Not dysmenorrhea (n %) | p-value | RR value | CI 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Carbohydrate | Less | 38 (59.4%) | 31 (48.4%) | 0.462a | 1.259 | 0.805 | 1.968 |

| More | 12 (18.8%) | 15 (23.4%) | 1.016 | 0.571 | 1.808 | ||

| Good | 14 (21.9%) | 18 (28.1%) | 1.000 | ||||

| Protein | Less | 39 (60.9%) | 30 (46.9%) | 0.093a | 1.159 | 0.796 | 1.687 |

| More | 5 (7.8%) | 13 (20.3%) | 0.569 | 0.254 | 1.278 | ||

| 20 (31.3%) | 21 (32.8%) | 1.000 | |||||

| Fat | Less | 36 (56.3%) | 37 (57.8%) | 0.0615 | 1.092 | 0.695 | 1.716 |

| More | 14 (21.9%) | 10 (15.6%) | 1.292 | 0.772 | 2.161 | ||

| Good | 14 (21.9%) | 17 (26.6%) | 1.000 | ||||

a Chi-square.

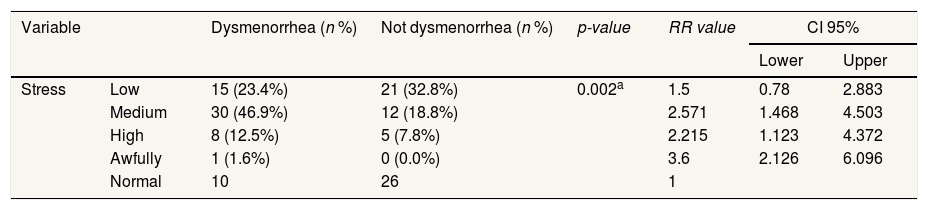

Respondents who experienced dysmenorrhea had the most moderate stress, namely, 30 respondents (46.9%), and respondents who did not experience dysmenorrhea had the most normal stress, namely 26 respondents (0.0%). Chi-square test results obtained p=0.002 (p<0.05). This shows there is a relationship between stress with the incidence of dysmenorrhea (Table 4).

The impact of stress analysis with dysmenore events.

| Variable | Dysmenorrhea (n %) | Not dysmenorrhea (n %) | p-value | RR value | CI 95% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Stress | Low | 15 (23.4%) | 21 (32.8%) | 0.002a | 1.5 | 0.78 | 2.883 |

| Medium | 30 (46.9%) | 12 (18.8%) | 2.571 | 1.468 | 4.503 | ||

| High | 8 (12.5%) | 5 (7.8%) | 2.215 | 1.123 | 4.372 | ||

| Awfully | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3.6 | 2.126 | 6.096 | ||

| Normal | 10 | 26 | 1 | ||||

a Chi-square.

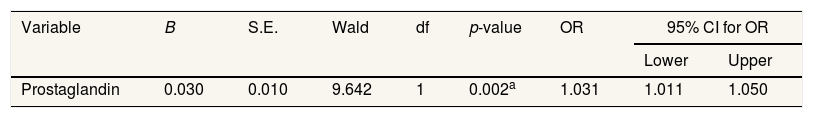

Prostaglandin levels with p-value 0.002, which means <0.005. This shows that the incidence of dysmenorrhea influences prostaglandin (pgf2α) levels (Table 5).

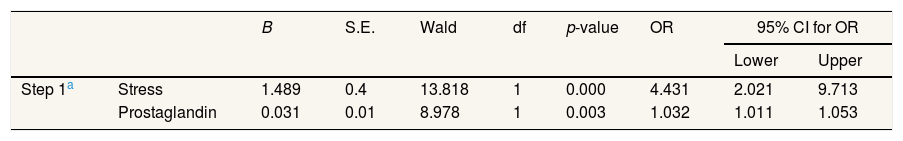

Variables that are very influential on dysmenorrhea are stress with a value of p=0.000 and prostaglandins with a value of p=0.003 compared to other variables) (Table 6).

Influence analysis of macronutrient intake, stress, prostaglandin levels (Pgf2α) with dysmenorrhea incidence.

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | p-value | OR | 95% CI for OR | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Step 1a | Stress | 1.489 | 0.4 | 13.818 | 1 | 0.000 | 4.431 | 2.021 | 9.713 |

| Prostaglandin | 0.031 | 0.01 | 8.978 | 1 | 0.003 | 1.032 | 1.011 | 1.053 | |

Table 1 shows that most 16-year-old are as many as 74 people (57.8%). Respondents with the most menstrual cycles are 21–35 days of 124 people (96.9%). Respondents with the most menstrual period of 5–7 days are 89 people (69.5%). Table 2 shows that respondents who have the highest intake of carbohydrate macronutrients are less than 69 people (53.9%), the maximum protein intake of macronutrients is less than 69 people (53.9%), consumption of the fattest macronutrient intake is less than 73 people (57.0%). Most of the Respondents have low prostaglandin levels of 66.4%. Previously, the cut-off point was determined at prostaglandin levels (pgf2α) using a ROC curve with 50.00% sensitivity and 82.81% specificity values. Respondents who have been dysmenorrhea as much as 64 (50%) and did not suffer from dysmenorrhea as much as 64 respondents (50%).

Carbohydrates are one part of the macronutrients contained in foods. High protein levels in foods will increase the levels of tyrosine that implicate the increase in the synthesis of dopamine, the dopamine metabolite. Dopamine is purported to improve satisfaction and mood. In general, a recognized breakfast contributes positively to the quality of the diet, the intake of macronutrients and micronutrients, body mass index, lifestyle, and positively affects behavioral, cognitive, and academic performance in children aged-school.15,16 The results of this study with a Chi-square test showed no influence between the intake of macronutrients (carbohydrates, proteins, fats) with the incidence of dysmenorrhea.

Fatty acids are an essential component in cell membranes as they can produce energy. Therefore, women should be consuming foods high in omega-3 fatty acids, e.g., fish (salmon, tuna, mackerel, dried fish), fish oil, soy, eggs, meat, shrimp, and fruits. Conversely, consuming foods that are low in omega-3 can increase pain dysmenorrhea.17 The results of this study differ from those done in Georgia, stating that energy and fat intake are connected with dysmenorrhea events.

Tables 3 and 4 indicates that there is a stress effect with the occurrence of Dysmenore with the value p=0.002. Stress can exacerbate the current state of menstruation. The research is in line with India's research that there is a significant relationship between dysmenorrhea and stress. In addition, the Korean nursing Program recommends that teenagers improve their health and encourage them to eat regularly to reduce stress when menstruation.18

The cause of pain is dysmenorrhoea due to an increase in prostaglandin hormones. This hormone results in uterine contractions and vascular vasoconstriction. Blood flow that leads to the uterus decreases so that the uterus does not get adequate oxygen, causing pain.19 In line with the test results in the 3.5 table indicates that the incidence of dysmenorrhea has an influence on the level of prostaglandins (Pgf2α) with a value p 0.002 (<0.005).

A multivariate analysis using a backward logistics regression equation found that a variable that strongly affects dysmenorrhea is stress with the value p=0.000 and prostaglandins with a value p=0.003 compared to other variables. Increased levels of prostaglandins proved to have been found in menstrual fluid in women with severe dysmenorrhea, especially during the first two days of menstruation. Painful menstruation affects the biochemical and cellular processes throughout the body, including the brain and psychological. During stress, the body will produce excessive adrenal, estrogen, progesterone, and prostaglandin hormones. Increased estrogen hormones may increase excessive uterine contractions. In addition, increased adrenal hormones can cause muscle tension of the uterus, which makes excessive contraction so which will cause a taste of pain.20,21

ConclusionLevels of prostaglandins (pgf2α) affect the incidence of dysmenorrhea in the event of a change in the period of menstrual hormones, i.e., prostaglandins can reduce or temporarily inhibit the blood supply to the uterus, causing the uterus to lack oxygen and cause myometrium contraction so that there is pain. Furthermore, stress is very influential with dysmenorrhea, among other variables, because of the more stressful one in the face of a problem than the pain that is felt when menstruation is increasing so that stress can interfere with the work of the endocrine system. A person with an insufficient intake of nutrients has a higher risk of being affected by Dysmenore. For that, teenagers must meet the intake of macronutrients consisting of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, especially during menstruation.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.