Analyze how pandemics contribute to the increase in social inequalities in the health sector.

MethodData are taken from Eurobarometer 97.3. We use the Generalized Structural Equation Model (GSEM) methodology for this analysis.

ResultsPeople with lower socio-economic status, considered to be of lower social class, living in areas with worse infrastructure for practicing physical activity, and in countries with high levels of social inequality, are less likely to engage in leisure time physical activity. In addition, these individuals are more likely to interrupt physical activity practices as a result of COVID-19. In contrast, people of higher socio-economic status, considered to be of upper class, living in contexts where there are opportunities for physical activity, and in countries with low levels of social inequality, are more likely/ to belong to the group of those who increased the frequency of practicing physical activity in free time/ to have increased the frequency of their leisure time physical activity.

ConclusionsThere are widespread inequalities in leisure time physical activity linked to personal variables (social status and subjective social class) and contextual variables (infrastructures and Gini Index) that were significantly aggravated with the COVID-19 pandemic.

Investigar si esta tesis se cumple con la pandemia de COVID-19.

MétodoLos datos provienen del Eurobarómetro 97.3. Para este análisis se utilizó la metodología del Modelo de Ecuaciones Estructurales Generalizadas (GSEM).

ResultadosLas personas con un nivel socioeconómico más bajo, consideradas de una clase social inferior, que viven en áreas con una infraestructura deficiente para la práctica de actividad física, y en países con altos niveles de desigualdad social, tienen menos probabilidades de participar en actividad física en su tiempo libre. Además, estas personas fueron más propensas a interrumpir la práctica de actividad física como resultado de la COVID-19. En contraste, las personas con un nivel socioeconómico más alto, consideradas de una clase social superior, que viven en contextos donde existen oportunidades para la actividad física y en países con bajos niveles de desigualdad social, tienen más probabilidades de haber aumentado la frecuencia de la práctica de actividad física en su tiempo libre o la frecuencia de actividad física en su tiempo de ocio.

ConclusionesExisten desigualdades generalizadas en la actividad física en el tiempo de ocio relacionadas con variables personales (estatus social y clase social subjetiva) y variables contextuales (infraestructuras e índice de Gini), que se agravaron significativamente con la pandemia de COVID-19.

Physical activity (PA) is considered to be essential for human health.1–3 There are different domains in which PA can be carried out, which can be divided into four categories: transport PA (TPA), occupational PA (OPA), housing PA (HPA) and leisure time PA (LTPA). We analyse LTPA of European Union (EU) citizens in relation to social inequalities, and the stopping of or increase in frequency of LTPA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Several studies agree that during COVID-19 there was an increase in interest and practice of physical activity4,5 mainly due to greater awareness about health and the increase in free time to do it. However, this increase was not uniform for the entire population, but greater in the high SES and SSC groups who live in areas that provide access to infrastructures offering opportunities for practising physical activity. At the same time, an abandonment was observed on the following group: people living in countries with high levels of inequality and people with low SES and SSC living in areas with poor infrastructure to practice LTPA.

There is a certain consensus among scientists about the influence of social inequalities on health and health-related activities such as physical exercise, especially LTPA. Among these social inequalities are those related to social status (SES), subjective social class (SSC), infrastructure and opportunities to practice in the community where people live (AREAOPPORT) and inequalities in income distribution across countries, as measured by the Gini index. Given this influence, scientists believe that reducing social inequalities would contribute to more physical activity and improve the health and well-being of the population.6,7

Social inequalities and their influence on the practice of physical activity must be analysed from an individual and contextual perspective. First, we analyse LTPA from an individual perspective, and how it is affected by SSC and by SES, measured by education, profession and income.8–24 The research shows how two people with the same objective SES, if they subjectively perceive themselves to be of a different class (subjective SES), those who consider themselves to be of a higher social class are more likely to practice LTPA.25–27Secondly, we must analyse two different contexts at a contextual level: one of them refers to the infrastructure of the area where people live and the opportunities offered to practice sports, and the other refers to the economic inequalities of the country of residence. It is more likely that less LTPA will be practiced in countries where there are greater inequalities as we shall measure using the Gini index.28

Data analysis from recent epidemics shows a negative impact on factors affecting health, as well as on income distribution. In these situations, the Gini index increased, implying higher income in the highest deciles and lower income in the lowest deciles. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a much greater social impact than other recent pandemics, due to financial or other factors.29,30 Evidence of this impact is reflected in the increase in social inequalities, public health and other activities associated with them, such as LTPA. In summary, the effects of the pandemic lead to an increase in social inequality and negative health behaviours associated with the lowest strata,31 which can specifically be observed in the area of physical activity.32–34We formulated two hypotheses for this research:

- •

Hypothesis H1: LTPA is related to the social inequalities of SES, SSC, OA and income inequality in the country.

- •

Hypothesis H2: the COVID-19 pandemic has led to an increase in inequalities in the practice of LTPA, producing an abandonment of it by the lowest social classes along with an increase by the most advantaged in the social structure.

Data are taken from Eurobarometer 97.3, collected between the months of April and May 2022, except for the Gini index which was taken from the World Bank Data. The Eurobarometer is a series of public opinion surveys in the European Union member countries. Eurobarometer 97.3 sampling size amounts to 26,569 cases of people, distributed between different countries as shown on Table S1 (Supplementary data).

The dependent variables we analyse are as follows: the practice of LTPA, the decrease in LTPA during COVID-19, and the increase during COVID-19. The independent variables to analyse the different behaviours of the different social groups are as follows: SES, SSC, OA and Gini index. The SES is the objective social status, measured by education, occupation and income. SSC is the subjective social class, measured by asking individuals to rank themselves relative to other people. The OA (AREAOPPORT) refers to the infrastructure for physical activity in the area where people live to engage in sports.

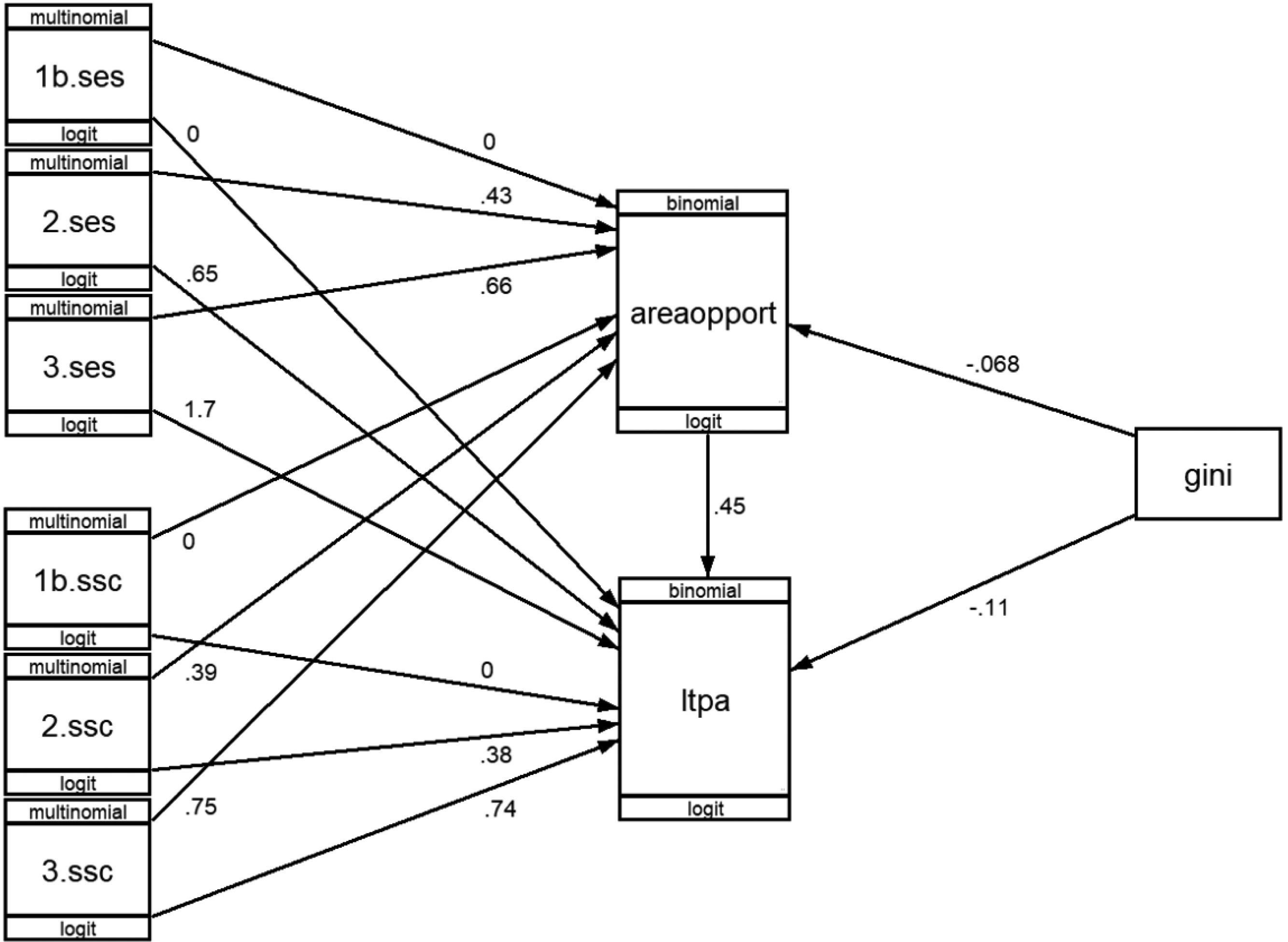

Data were analysed using the generalized structural equation modelling (GSEM), with the STATA program. GSEM is a generalization of SEM (structural equation modelling) for cases where nominal or ordinal variables are included in the analysis, as done in this research (Fig. 1). Structural equations require model adjustment, so the one that best fits the data is chosen. In the case of GSEM, the values used for adjustment are the AIC (Akaike information criterion) and BIC (Bayesian or Schwarz information criterion).

The beta coefficients (b) of regression resulting from the analysis were converted to odds ratios (OR) by raising it to its exponent. The interpretation of these values is done by comparing the data of a category serving as a base with the other categories of the variable. Thus, for example, in Table 1, the subjective social class variable (SES) takes low class as the reference category, which is equal to 1. The upper class has a value of 5.27. This indicates that for every 100 individuals from lower social class who engage in LTPA, we have 527 individuals from upper social class.

Practice of leisure time physical activity according to social inequalities. Values exp(b)=OR.

| LTPA (dependent variable) | exp(b)=OR | P>z |

|---|---|---|

| AREAOPPORT | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.57 | 0.000 |

| Gini index | 0.90 | 0.000 |

| SES | ||

| Low | 1.00 | |

| Middle | 1.92 | 0.000 |

| Upper | 5.27 | 0.000 |

| SSC | ||

| Working, lower-middle | 1.00 | |

| Middle | 1.46 | 0.000 |

| Upper, upper-middle | 2.10 | 0.000 |

| AREAOPPORT | ||

| Gini index | 0.93 | 0.000 |

| SES | ||

| Low | 1.00 | |

| Middle | 1.54 | 0.000 |

| Upper | 1.94 | 0.000 |

| SSC | ||

| Working-lower middle | 1.00 | |

| Middle | 1.47 | 0.000 |

| Upper-upper middle | 2.13 | 0.000 |

AREAOPPORT: class infrastructure and opportunities to practice in the community where people live; LTPA: leisure time physical activity; OR: odds ratio; SES: social status; SSC: subjective social class.

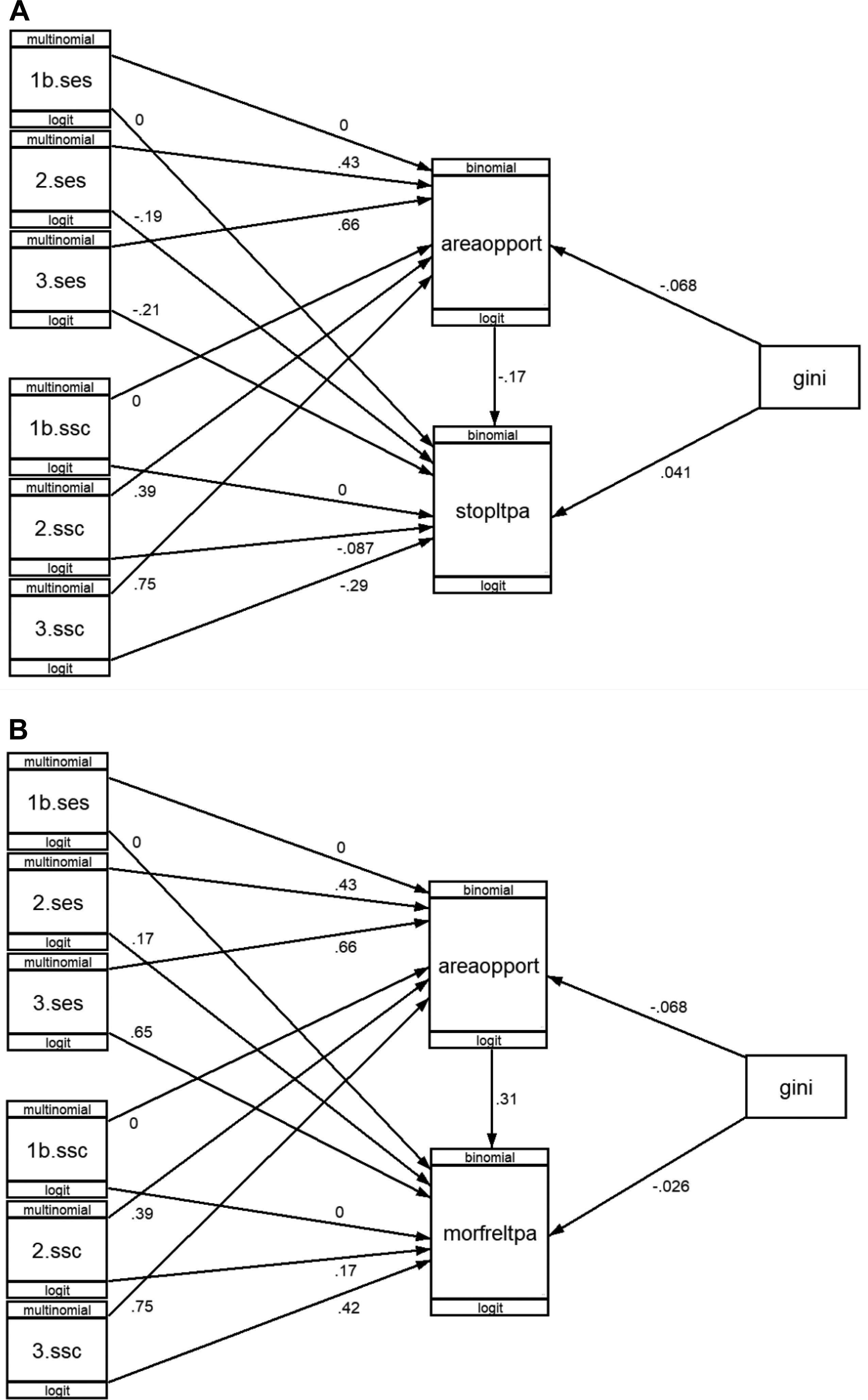

Regarding the interpretation of negative beta values (Fig. 2), which, when converted to OR, values lower than 1 are obtained, their interpretation is more understandable if we calculate their inverse values. For example, in Table 2, the value 0.83 of the middle SES is equivalent to a positive effect of (1/0.83) 1.2. This indicates that for every 100 individuals from the middle class who stop engaging in LTPA, we observe a decrease of 120 individuals from lower class also stopping in LTPA.

Influence of COVID-19 on practice of leisure time physical activity (LTPA) during COVID-19, according to social inequalities. B values. areaopport: class infrastructure and opportunities to practice in the community where people live; gini: Gini index; morefrltpa: more frequently leisure time physical activity; ses: social status; ssc: subjective social class; stopltpa: stopped practising leisure time physical activity.

Influence of COVID-19 on practice of leisure time physical activity during COVID-19, according to social inequalities. Values exp(b)=OR.

| Stopped practising LTPA during COVID-19 | Practised LTPA more frequently during COVID-19 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| exp(b)=OR | P>z | exp(b)=OR | P>z | ||

| STOPLTPA | MORFRELTPA | ||||

| AREAOPPORT | AREAOPPORT | ||||

| No | 1.00 | No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 0.85 | 0.001 | Yes | 1.36 | 0.000 |

| Gini index | 1.04 | 0.000 | Gini index | 0.97 | 0.000 |

| SES | SES | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | Low | 1.00 | ||

| Middle | 0.83 | 0.004 | Middle | 1.19 | 0.118 |

| Upper | 0.81 | 0.003 | Upper | 1.92 | 0.000 |

| SSC | SSC | ||||

| Working-lower middle | 1.00 | Working-lower middle | 1.00 | ||

| Middle | 0.92 | 0.065 | Middle | 1.18 | 0.010 |

| Upper, upper-middle | 0.75 | 0.000 | Upper, upper-middle | 1.52 | 0.000 |

| AREAOPPORT | AREAOPPORT | ||||

| Gini index | 0.93 | 0.000 | Gini index | 0.93 | 0.000 |

| SES | SES | ||||

| Low | 1.00 | Low | 1.00 | ||

| Middle | 1.54 | 0.000 | Middle | 1.54 | 0.000 |

| Upper | 1.94 | 0.000 | Upper | 1.94 | 0.000 |

| SSC | SSC | ||||

| Working-lower middle | 1.00 | Working-lower middle | 1.00 | ||

| Middle | 1.47 | 0.000 | Middle | 1.47 | 0.000 |

| Upper, upper middle | 2.13 | 0.000 | Upper,upper middle | 2.13 | 0.000 |

AREAOPPORT: class infrastructure and opportunities to practice in the community where people live; LTPA: leisure time physical activity; MOREFRLTPA: more frequently leisure time physical activity; SES: social status; SSC: subjective social class; STOPLTPA: stopped practising leisure time physical activity.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, practice in LTPA took the values 0 and 1. Stopping LTPA (STOPLTPA) took the values 0 and 1. Increase in LTPA (MORFRELTPA) took the values 0 and 1. Opportunities for PA in the area of residence (AREAOPPORT) took the values 0 and 1. SSC took the values 1 (working and lower-middle class), 2 (middle class) and 3 (upper and upper-middle class). The Gini index took values from 0 to 100, with the lowest country obtaining a value of 21.10 and the highest a value of 40.50.

The Gini index is a contextual variable, which indicates the equality of income within a country, thus helping us to compare people's LTPA practice according to the existing inequality in the country. Given that a principle of GSEM is to look for a model that fits the data well, it may happen that when a new variable is introduced, the data fit better or worse. Consequently, we conducted a test to analyse the fit of the model with and without the inclusion of the Gini index. The results show that when we include the Gini index in the analysis, the fit is better, lowering the AIC and BIC values. This leads to the need to include the Gini index in all analyses.

SES was calculated on the basis of three variables: occupation, education and economic situation. Occupation was divided into 6 categories, following the classification of Goldthorpe and the ESS working group (1995). The final calculation with the weighting of the different variables was as follows: occupation, categories from 1 to 6; difficulties in paying bills at the end of the month, always=2, sometimes=4, never=6; education, basic or incomplete=2, secondary=4, higher=6, studying=8. The total sum of the different categories ranges from 5 to 20, with the SES recoded into the following categories: low (5-10), middle (11-15) and high (16-20).

ResultsPerformance of LTPA according to SES, SSC, AREAOPPORT and Gini indexIn 2022, 76.5% of EU citizens carried out some type of LTPA. Nevertheless, this practice is different depending on the SES, SSC, AREAOPPORT and the distribution of wealth in the country where they live (Gini). Figure 1 shows the b values of the regression carried out using the GSEM. Table 1 shows the OR values that are the exponents of b. The variable that most influences is SES, so that for every 100 people with low SES (see OR value low=1) who practice LTPA we have 192 (see OR value 1.92) of middle SES and 527 of upper SES (see OR value 5.27). It is found that SSC has also an influence after controlling the effect of the other variables, so that among people of the same SES, if people consider themselves to be of a different class, this subjective assessment is also influencing the practice of LTPA. For every 100 people considered to be from working or lower-middle SSC who practice LTPA, we have 146 who are considered middle SSC and 210 who are considered upper or middle-higher SSC.

Contextual factors also play an important role in the practice of LTPA, both those related to the infrastructure of the community and those related to the inequalities of the country where people live. For every 100 LTPA practitioners who live in areas that they consider do not offer good opportunities for LTPA, we have 157 LTPA practitioners who do consider that the area where they live offers good opportunities. The Gini index value also has an impact. For every unit that the Gini index increases, the probability of LTPA decreases by 0.90.

In turn, the opportunities of the area where people live to carry out LTPA are conditioned by SES, SSC and the Gini index value. For every 100 people of low SES living in areas they consider offer opportunities for LTPA, we have 154 people of middle SES and 194 people of upper SES. Even after controlling for SES, subjective perception of social class (SSC) still plays a role. For every 100 people of lower class who say they live in areas that offer opportunities for LTPA, we have 147 who consider themselves middle class and 213 who consider themselves upper class. it is also influencing in the case of the Gini index, falling by 0.93 for each unit that the Gini index rises.

Influence of COVID-19 on stopping of or increase in frequency of leisure time physical activity, according to SES, SSC, OA and Gini indexCOVID-19 influenced the practice of LTPA. Some people were negatively influenced, others positively, and others remained the same. 15.7% of those who practised LTPA before COVID-19 stopped practising LTPA, 32.2% continued to practise LTPA but less frequently, 38.1% practised LTPA at the same level as before and 8.8% practised LTPA more frequently. We will focus on the analysis of those who stopped practising LTPA during COVID-19, and those who began practising LTPA more frequently. Figure 1 shows the b-values of the GSEM regression. Table 2 shows the OR values.

Stopping physical activity during the pandemic was influenced by inequality in the country of residence (Gini index), such that as inequality rises, so does the likelihood of stopping physical activity during COVID-19. For each unit increased in the Gini index, the OR increases by 1.04. The rest of the variables had a negative influence. The higher the social status, the lower the probability of abandonment of LTPA, with the OR of those belonging to middle SES being 0.83 compared to lower SES, and 0.81 in the upper SES. After controlling for SES, subjective perception of class also plays a role: those who consider themselves from SSC upper and upper-middle class have an OR of 0.75 compared to SSC working-lower. The opportunities to practise LTPA in the area where people live also have a negative influence. Those living in areas where infrastructure exist have an OR of 0.85 compared to those living in areas where infrastructure do not exist.

In the increase of LTPA during COVID-19, the influence of the predictor variables is completely opposite to that of stopping LTPA. As the value of the Gini index rises, the probability of more frequent LTPA falls. As SES, SSC and infrastructure for LTPA in the area where people live increases, the OR of the LTPA variable also rises more frequently: for every 100 people of low SES, we find 192 of SES upper; for every 100 of working and lower-middle SSC, we find 118 of middle SES and 152 from upper and upper-middle SES. For every 100 people living in areas where there is no adequate infrastructure for LTPA, there are 136 living in areas with adequate infrastructure.

Discussion76.5% of EU citizens practise LTPA. Of these citizens, 55.1% said they were motivated by health reasons. However, there are large differences in the practice of LTPA according to social inequalities as measured by different individual and contextual factors.

Inequality of LTPA practice according to social conditionsThe difference is especially large in the case of SES, with the ratio between low and high SES being 1 to 5.27. That is, for every 100 people of low SES practising LTPA, there are 527 of high SES. While other analyses draw similar conclusions in terms of the influence of SES, such that as SES rises, the likelihood of LTPA practice also rises8–18,20–23 in our analysis the results obtained are very high and very conclusive, as the P>z value is 0.000.

Nonetheless, after removing the effect of SES, it is also necessary to take into account the subjective perception of social class (SSC), such that between people of the same SES, if they consider themselves from lower class to upper class, the ratio is 1 to 2.10. In this sense, we conclude that it is essential to include subjective class perception in addition to SES in order to analyse the behaviour of the population in LTPA.25–27,34

Contextual factors are also essential for the practice of LTPA, both in terms of the community and the country where people live. People living in areas with adequate infrastructure for LTPA, as well as those living in countries with low social inequalities (Gini index), are more likely to practise LTPA.28

The influence of COVID-19 on the increase in inequalitiesPandemics in general contribute to the increase of social inequalities in health and healthy living practices.29,30 In the case of COVID-19, several researchers predicted that these inequalities would increase4,32,33 and our study demonstrates that this has been true. People with low SES, low SSC, AREAOPPORT deficits and living in countries with high inequalities were already the least likely to practise LTPA, and COVID-19 exacerbated this situation. In contrast, people who intensified their LTPA are those with high SES and high SSC, living in AREAOPPORT and in countries with low inequality.

Therefore, being able to reduce inequalities between people in order to avoid the abandonment in LTPA, and even practise it more frequently, must be associated with reducing inequalities in SES and SSC, along with building infrastructure in residential areas and reducing social inequalities within countries.

Strengths and limitationsThis EU-wide study presents an analysis based on 26,569 interviews on the practice of LTPA, based on social inequalities. It strongly reveals the high influence of SES, SSC, AREAOPPORT and country inequalities on LTPA practice.

We also used data from the first quarter of 2022 to analyse the influence of COVID-19, especially in the group of people who used to practise and stopped, as well as those who increased the intensity of their practice. COVID-19 was shown to have increased social differences.

The main limitation we may encounter in the future is a lack of data which would allow us to analyse whether the situation observed during COVID-19 reverses or whether the abandonment of LTPA continues, i.e. whether it is temporary or permanent. To this end, it is necessary to include specific questions in the Eurobarometers that provide information on the practice of physical activity among Europeans. Finally, it would be necessary to monitor the social policies put in place by the countries in order to see whether they are helping to reduce, maintain or even increase disparities.

ConclusionsLTPA performs unequally across the population according to individual (SES and SSC) and contextual factors (AREAOPPORT and country inequality, Gini index). Although other authors have reached similar results, those obtained in our analysis are extremely high and conclusive.

During COVID-19, a kind of Matthew effect occurred, with an increase in interest in and practice of physical activity among people with high SES, SSC, AREAOPPORT and living in countries with a low Gini index value. In contrast, people with low SES, SSC, AREAOPPORT and living in countries with a high Gini index value stopped LTPA during COVID-19.

The increase in LTPA practice and thus the improvement of health and life expectancy has an important causal relationship with individual and contextual socio-demographic variables, such as social status (SES), subjective social class (SSC), infrastructures and opportunities (AREAOPPORT) and the Gini index. This clearly shows the need to implement public policies aimed at reducing social inequality at regional, national and European level.

The practice of physical activity is conditioned by social inequalities, with people living in the worst conditions being the least physically active in their leisure time. Social crises, such as pandemics, affect the disadvantaged more severely, threreby increasing social inequality.

What does this study add to the literature?Leisure time physical activity performs unequally across the population according to individual and contextual factors, and although other authors have arrived at similar results, those obtained in our analysis are extremely high and conclusive.

What are the implications of the results?It would be necessary to monitor the social policies which countries put in place to see whether they are helping to reduce, maintain or even increase disparities.

Microdata from Eurostat (Eurobarometer 97.3) are protected by Regulation (EU) 2018/1725 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 October 2018 on the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data by the Union institutions, bodies, offices and agencies and on the free movement of such data, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 45/2001 and Decision No 1247/2002/EC.

Availability of databases and material for replicationAll surveys of the European Union are available in https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/browse/all/series/4961 (accessed on 4 October 2022).

Editor in chargeVanessa Santos.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsBackground: D. Álvarez-Lourido and J.L. Paniza Prados. Methodology: D. Álvarez-Lourido, J.L. Paniza Prados and A. Álvarez-Sousa. Software: A. Álvarez-Sousa. Investigation: J.L. Paniza Prados and A. Álvarez-Sousa. Resources: J.L. Paniza Prados. Data curation: D. Álvarez-Lourido and J.L. Paniza Prados. Writing, original draft: D. Álvarez-Lourido, J.L. Paniza Prados and A. Álvarez-Sousa. Writing, review and editing: D. Álvarez-Lourido, J.L. Paniza Prados and A. Álvarez-Sousa. Visualization: D. Álvarez-Lourido. Supervision: D. Álvarez-Lourido and A. Álvarez-Sousa.

FundingNone.

None.