To describe sleep-wake patterns in young children, based on sleep characteristics in early infancy and preschool ages, identifying their main sociodemographic characteristics, and to assess the association between different sleep characteristics at both ages.

MethodWe included 1092 children from the Generation XXI birth cohort, evaluated at six months and four years of age, by face-to-face interviews. Sleep patterns were constructed through latent class analysis and structured equation modeling, including data on wake-up time and bedtime, afternoon naps, locale of nighttime sleep and night awakenings. To estimate the association between sociodemographic characteristics and sleep patterns, odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were computed using logistic regression.

ResultsTwo sleep patterns were identified through latent class analysis: pattern 1 was characterized by earlier bedtime and wake-up times, while pattern 2 was defined by later times. When compared with pattern 1, pattern 2 was more frequent among children whose mothers had changed from partnered to not partnered until preschool age and those who did not stay at the kindergarten, and was less common among those with siblings. Through structured equation modeling, an aggregating factor was identified at preschool age, which was mainly correlated with bedtime and wake-up time. A positive association between sleep characteristics evaluated in early infancy and in preschool ages was observed.

ConclusionsSleep patterns and circadian sleep preferences seem to be developed early in life, which highlight the importance of promoting an adequate sleep hygiene from infancy, assuming its impact on sleep quality during the life course.

Describir los patrones de sueño en niños, a partir de las características del sueño en la primera infancia y preescolar, identificando sus características sociodemográficas, y evaluar la asociación entre las características del sueño en ambas edades.

MétodoSe incluyeron 1092 niños de la cohorte Generación XXI, evaluados a los 6 meses y los 4 años de edad, mediante entrevistas en persona. Los patrones de sueño se identificaron mediante análisis de clases latentes y modelos de ecuaciones estructuradas, utilizando datos sobre la hora de despertarse y acostarse, las siestas de la tarde, el lugar del sueño nocturno y los despertares nocturnos. Para estimar la asociación entre las características sociodemográficas y los patrones de sueño se calcularon odds ratio con intervalos de confianza del 95% mediante regresión logística.

ResultadosSe identificaron dos patrones de sueño: el patrón 1 se caracterizó por acostarse y levantarse más temprano; el patrón 2, por tiempos más tardíos. El patrón 2 fue más frecuente entre los niños con madres que cambiaron de pareja a no pareja y que no permanecieron en el jardín de infancia, y menos común entre aquellos con hermanos. Se identificó un factor agregante en la edad preescolar, correlacionado con la hora de acostarse y despertarse. Se observó una asociación positiva entre las características del sueño evaluadas en la primera infancia y en edades preescolares.

ConclusionesLos patrones del sueño parecen desarrollarse temprano en la vida, lo que destaca la importancia de promover una adecuada higiene del sueño desde la infancia.

Sleep in children is essential for their development, and has an important role in physical growth, cognitive and psychomotor functions, as well as in emotional and behavior components.1,2 Additionally, inadequate sleep quality and quantity in early infancy have potential long-term implications, influencing child or adolescent's development,3 and are also associated with poorer long-term outcomes among young4 and middle age adults.5 In this context, it is also important to refer that sleep-wake patterns are recognized to be immature at birth and the most rapid changes in maturation and consolidation in sleep occur during the first six months of life.6 Furthermore, since pediatric sleep disturbances often persist along time, and patterns during infancy seem to be one of the predictors of sleep quality in older ages,7 special attention should be given to sleep during this stage of life. Thus, a more comprehensive knowledge about sleep patterns during the first years of life may contribute to the development of intervention programs in order to promote healthy sleep patterns since early ages and, consequently, diminishing the burden of sleep-related health consequences later in life.

Previous studies have shown that sleep-wake patterns are influenced by the interaction of a wide range of intrinsic and extrinsic factors, namely the infants’ physiological maturation process, medical characteristics, behavioral self-regulation abilities, as well as parental influences, interactive behaviors and environmental contexts.1,8 However, few studies evaluated the changes of sleep patterns along the different ages of childhood, and little is known about the association of specific sleep characteristics in infants and their later sleep patterns. Likewise, a complete sociodemographic characterization of these patterns is rarely addressed,9 and may provide crucial information to delineate future preventive actions.

Therefore, this study aims: 1) to describe sleep-wake patterns in young children, based on sleep characteristics in early infancy and preschool ages, identifying their main sociodemographic characteristics; 2) to assess the association between different sleep characteristics at both ages.

MethodStudy populationThis study is based on the Portuguese population-based birth cohort, Generation XXI, explained in detail elsewhere.10 A total of 8647 newborns were enrolled in this cohort. The recruitment and baseline evaluation occurred between April 2005 and August 2006 in all the five public maternity units of the metropolitan area of Porto, Portugal, where mothers were consecutively invited to participate after delivery. At birth, 91.4% of the invited mothers accepted to participate.

A first follow-up was conducted at six months of age in a sub-sample of children, and afterwards they were evaluated at four years of age. For the purpose of this study, we only included singleton newborns, which had participated in the six months’ follow-up and that were reevaluated at four years of age by face-to-face interviews (n=1178). Children with missing data on key variables were also excluded, with 1092 children remaining for analysis.

The local institutional ethics committee and the Portuguese Data Protection Authority approved the study and all mothers provided written informed consent in each one of the evaluations.

Data collectionData on sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics were collected at baseline, at six months and at four years after delivery, by trained interviewers in face-to-face interviews, using structured questionnaires.

Sleep characteristics were evaluated through a structured questionnaire applied at six months and four years of age, and were classified similarly at both ages, except for night awakenings. The variables “children's wake-up and bedtime hours” and “duration of afternoon naps” were categorized in tertiles, considering their discrete nature. Locations of nigh-time sleep were grouped in two categories: children's bedroom (alone or with siblings) and other location (e.g. parents’ bedroom). Night awakenings at six months were categorized as: never,<3 times/week, ≥3 times/week occurring 1 time/night, and ≥3 times/week occurring ≥2 times/night. At four years of age, night awakenings were grouped as: never or<1 time/month,<1 time/week but at least 1 time/month,>1 time/week, and every night.

Statistical analysisSleep patterns included five distinct characteristics evaluated at 6 months and at 4 years of age, namely bedtime, wake-up time, afternoon naps, locale of nighttime sleep as well as night awakenings, and were identified using latent class analysis.11 This methodology distinguishes clusters of individuals from a sample (patterns), homogeneous within groups, considering that individual responses in a range of items is explained by a categorical (unmeasured) latent variable — “latent class”. In the present study, the number of sleep patterns was defined according to the Bayesian information criteria (BIC), and the profiles of probabilities in each sleep characteristic's category, conditionally on pattern membership, were used to interpret children's sleep patterns.

In order to explore the association between sleep characteristics at six months of age and at four years of age, a structural equation modeling was used. The global goodness of fit of the underlying structure was evaluated using four fit indexes of confirmatory factor analysis: the comparative fit index (CFI),12 the non-normed-fit-index also known as the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI),13 the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the weighted root mean squared residual (WRMR),14 CFI and TLI indicate an acceptable model fit with values>0.90, and a good model fit with values>0.95;15 values of RMSEA<0.08 and<0.05 indicates an acceptable or good model fit, respectively, and values WRMR<0.90 indicates a good model fit.16

To estimate the association between sociodemographic characteristics and sleep patterns, odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were computed using unconditional logistic regression. All models included the variables maternal age, education level, working condition and marital status, and children's siblings and daytime caregiver. The association of other maternal and children's characteristics with sleep patterns were tested, but since they were not significant they were trimmed from the models.

All analyses were conducted using Mplus 5® and STATA®, version 11.2 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

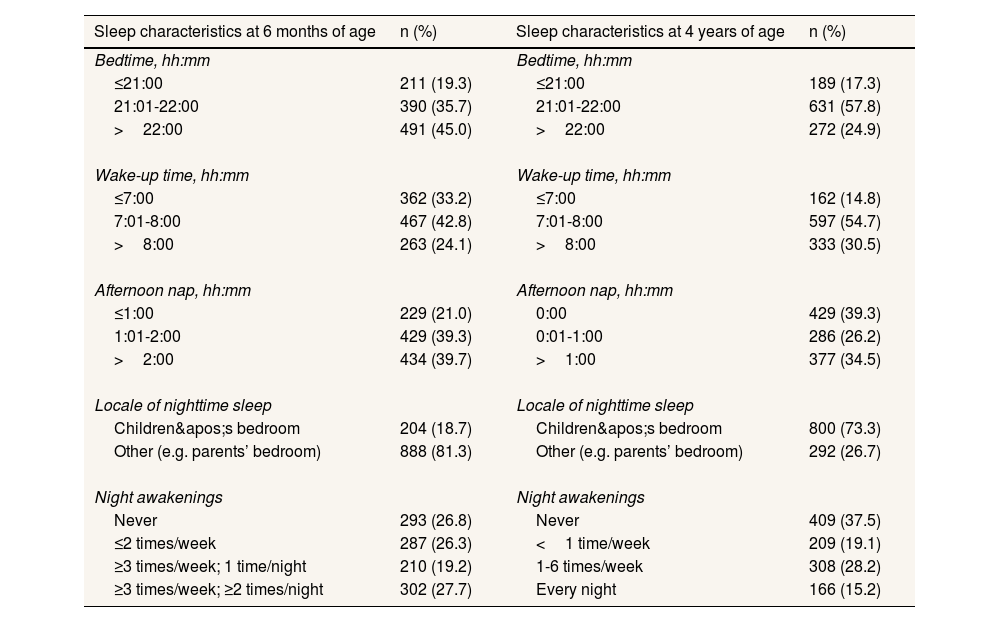

ResultsSleep characteristics during childhood are summarized in Table 1. Overall, children at four years of age had an earlier bedtime than at six months (after 22h: 24.9% vs. 45.0%). From six months to four years of age, an increase in the wake-up time was also observed: in the former age, two-thirds of the children woke-up after 7:00, whereas at the latter, this proportion was 85.2%. Regarding afternoon naps, at four years of age two-fifths of children did not nap during the afternoon. In addition, at six months of age 18.7% of the children slept in their bedroom (alone or with siblings), this proportion being higher at four years (73.3%). With increasing age, a decrease on the frequency of night awakenings was also noted (never: 26.8% vs. 37.5%).

Sleep characteristics at six months and at four years of age.

| Sleep characteristics at 6 months of age | n (%) | Sleep characteristics at 4 years of age | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedtime, hh:mm | Bedtime, hh:mm | ||

| ≤21:00 | 211 (19.3) | ≤21:00 | 189 (17.3) |

| 21:01-22:00 | 390 (35.7) | 21:01-22:00 | 631 (57.8) |

| >22:00 | 491 (45.0) | >22:00 | 272 (24.9) |

| Wake-up time, hh:mm | Wake-up time, hh:mm | ||

| ≤7:00 | 362 (33.2) | ≤7:00 | 162 (14.8) |

| 7:01-8:00 | 467 (42.8) | 7:01-8:00 | 597 (54.7) |

| >8:00 | 263 (24.1) | >8:00 | 333 (30.5) |

| Afternoon nap, hh:mm | Afternoon nap, hh:mm | ||

| ≤1:00 | 229 (21.0) | 0:00 | 429 (39.3) |

| 1:01-2:00 | 429 (39.3) | 0:01-1:00 | 286 (26.2) |

| >2:00 | 434 (39.7) | >1:00 | 377 (34.5) |

| Locale of nighttime sleep | Locale of nighttime sleep | ||

| Children's bedroom | 204 (18.7) | Children's bedroom | 800 (73.3) |

| Other (e.g. parents’ bedroom) | 888 (81.3) | Other (e.g. parents’ bedroom) | 292 (26.7) |

| Night awakenings | Night awakenings | ||

| Never | 293 (26.8) | Never | 409 (37.5) |

| ≤2 times/week | 287 (26.3) | <1 time/week | 209 (19.1) |

| ≥3 times/week; 1 time/night | 210 (19.2) | 1-6 times/week | 308 (28.2) |

| ≥3 times/week; ≥2 times/night | 302 (27.7) | Every night | 166 (15.2) |

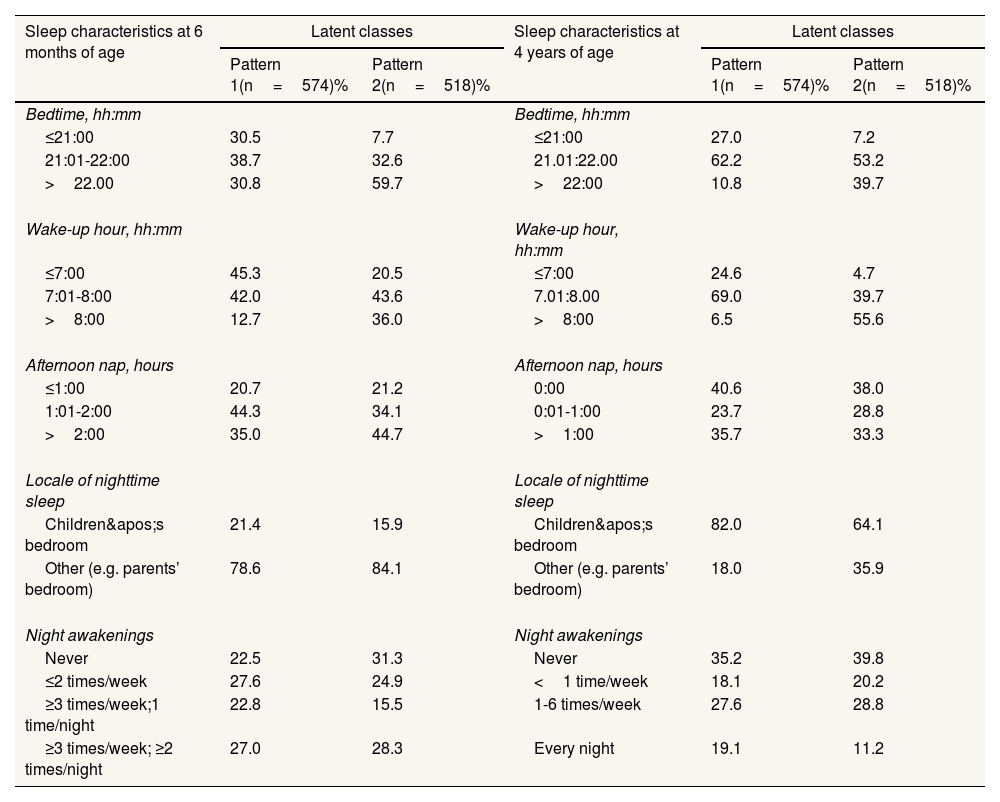

To identify sleep patterns in childhood, a latent class analysis was performed, which supported a subdivision in two sleep patterns: pattern 1 and pattern 2 (BIC=21,856.291). The average latent class probability for most likely latent class membership was higher than 80% for both classes (81.9% for pattern 1 and 83.2% for pattern 2). The major differences between both patterns were mainly related with bedtime and wake-up time. In fact, whereas the pattern 1 presented earlier bedtime and wake-up time, pattern 2 had higher proportions of children with later bedtime and wake-up time, similarly at both ages. in addition, pattern 2 was characterized by lower proportions of children sleeping in their own bedroom at four years of age, when compared with pattern 1 (Table 2).

Percentage of subjects in each sleep characteristics’ category, according to the two latent classes.

| Sleep characteristics at 6 months of age | Latent classes | Sleep characteristics at 4 years of age | Latent classes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern 1(n=574)% | Pattern 2(n=518)% | Pattern 1(n=574)% | Pattern 2(n=518)% | ||

| Bedtime, hh:mm | Bedtime, hh:mm | ||||

| ≤21:00 | 30.5 | 7.7 | ≤21:00 | 27.0 | 7.2 |

| 21:01-22:00 | 38.7 | 32.6 | 21.01:22.00 | 62.2 | 53.2 |

| >22.00 | 30.8 | 59.7 | >22:00 | 10.8 | 39.7 |

| Wake-up hour, hh:mm | Wake-up hour, hh:mm | ||||

| ≤7:00 | 45.3 | 20.5 | ≤7:00 | 24.6 | 4.7 |

| 7:01-8:00 | 42.0 | 43.6 | 7.01:8.00 | 69.0 | 39.7 |

| >8:00 | 12.7 | 36.0 | >8:00 | 6.5 | 55.6 |

| Afternoon nap, hours | Afternoon nap, hours | ||||

| ≤1:00 | 20.7 | 21.2 | 0:00 | 40.6 | 38.0 |

| 1:01-2:00 | 44.3 | 34.1 | 0:01-1:00 | 23.7 | 28.8 |

| >2:00 | 35.0 | 44.7 | >1:00 | 35.7 | 33.3 |

| Locale of nighttime sleep | Locale of nighttime sleep | ||||

| Children's bedroom | 21.4 | 15.9 | Children's bedroom | 82.0 | 64.1 |

| Other (e.g. parents’ bedroom) | 78.6 | 84.1 | Other (e.g. parents’ bedroom) | 18.0 | 35.9 |

| Night awakenings | Night awakenings | ||||

| Never | 22.5 | 31.3 | Never | 35.2 | 39.8 |

| ≤2 times/week | 27.6 | 24.9 | <1 time/week | 18.1 | 20.2 |

| ≥3 times/week;1 time/night | 22.8 | 15.5 | 1-6 times/week | 27.6 | 28.8 |

| ≥3 times/week; ≥2 times/night | 27.0 | 28.3 | Every night | 19.1 | 11.2 |

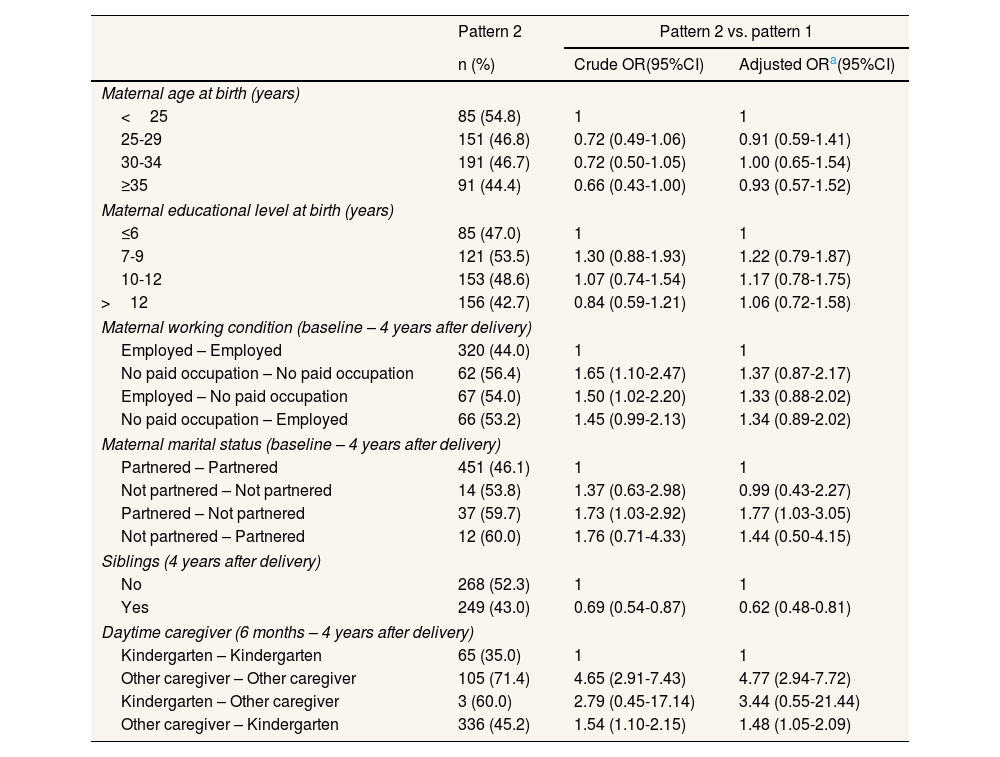

When considering the main sociodemographic characteristics of sleep patterns, children whose mothers were partnered at baseline and not partnered at four years of age (OR: 1.77; 95%CI: 1.03-3.05) were more likely to present the pattern 2. This pattern was less frequent among children with siblings (OR: 0.62; 95%CI: 0.48-0.81). Similarly, children that did not stay at kindergarten were more prone to be classified with pattern 2, particularly if this was maintained at four years of age (OR: 4.77; 95%CI: 2.94-7.72) (Table 3).

Association between socio-demographic characteristics and the pattern 2.

| Pattern 2 | Pattern 2 vs. pattern 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Crude OR(95%CI) | Adjusted ORa(95%CI) | |

| Maternal age at birth (years) | |||

| <25 | 85 (54.8) | 1 | 1 |

| 25-29 | 151 (46.8) | 0.72 (0.49-1.06) | 0.91 (0.59-1.41) |

| 30-34 | 191 (46.7) | 0.72 (0.50-1.05) | 1.00 (0.65-1.54) |

| ≥35 | 91 (44.4) | 0.66 (0.43-1.00) | 0.93 (0.57-1.52) |

| Maternal educational level at birth (years) | |||

| ≤6 | 85 (47.0) | 1 | 1 |

| 7-9 | 121 (53.5) | 1.30 (0.88-1.93) | 1.22 (0.79-1.87) |

| 10-12 | 153 (48.6) | 1.07 (0.74-1.54) | 1.17 (0.78-1.75) |

| >12 | 156 (42.7) | 0.84 (0.59-1.21) | 1.06 (0.72-1.58) |

| Maternal working condition (baseline – 4 years after delivery) | |||

| Employed – Employed | 320 (44.0) | 1 | 1 |

| No paid occupation – No paid occupation | 62 (56.4) | 1.65 (1.10-2.47) | 1.37 (0.87-2.17) |

| Employed – No paid occupation | 67 (54.0) | 1.50 (1.02-2.20) | 1.33 (0.88-2.02) |

| No paid occupation – Employed | 66 (53.2) | 1.45 (0.99-2.13) | 1.34 (0.89-2.02) |

| Maternal marital status (baseline – 4 years after delivery) | |||

| Partnered – Partnered | 451 (46.1) | 1 | 1 |

| Not partnered – Not partnered | 14 (53.8) | 1.37 (0.63-2.98) | 0.99 (0.43-2.27) |

| Partnered – Not partnered | 37 (59.7) | 1.73 (1.03-2.92) | 1.77 (1.03-3.05) |

| Not partnered – Partnered | 12 (60.0) | 1.76 (0.71-4.33) | 1.44 (0.50-4.15) |

| Siblings (4 years after delivery) | |||

| No | 268 (52.3) | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 249 (43.0) | 0.69 (0.54-0.87) | 0.62 (0.48-0.81) |

| Daytime caregiver (6 months – 4 years after delivery) | |||

| Kindergarten – Kindergarten | 65 (35.0) | 1 | 1 |

| Other caregiver – Other caregiver | 105 (71.4) | 4.65 (2.91-7.43) | 4.77 (2.94-7.72) |

| Kindergarten – Other caregiver | 3 (60.0) | 2.79 (0.45-17.14) | 3.44 (0.55-21.44) |

| Other caregiver – Kindergarten | 336 (45.2) | 1.54 (1.10-2.15) | 1.48 (1.05-2.09) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

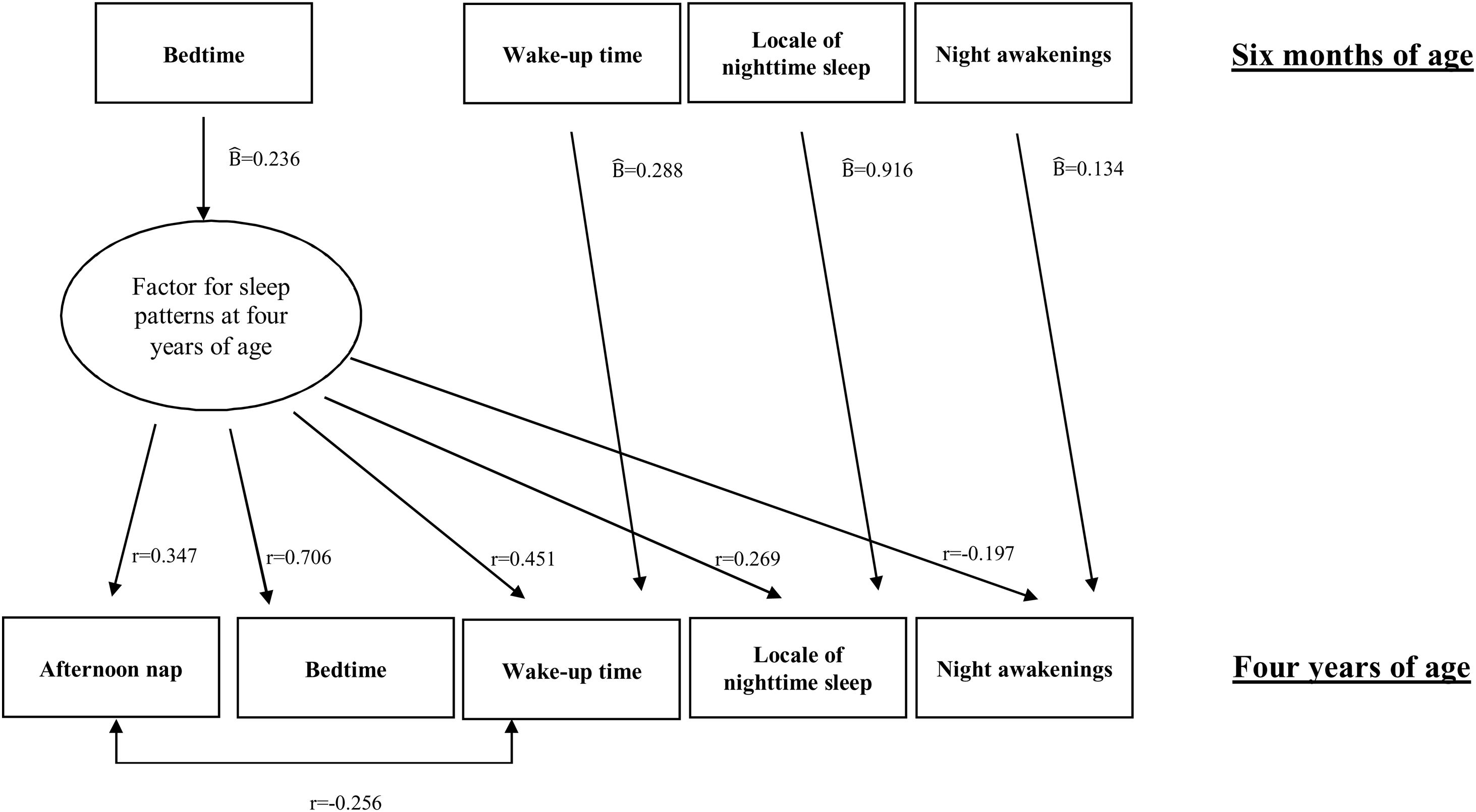

Additional analyses were performed in order to ascertain the possible association between each sleep characteristics measured in early infancy and in preschool ages. An aggregating factor was identified at four years of age (X2 (18)=30.065; p=0.0368; CIF=0.959; TLI=0.938; RMSEA=0.025; WRMR=0.894), as shown in Figure 1. This factor was statistically correlated with all sleep characteristics measured at preschool ages, particularly with bedtime (r=0.706; p<0.001) and wake-up time (r=0.451; p<0.001). Children with higher scores in this factor were more likely to go to bed and to wake-up later, to have higher duration of afternoon naps, to not sleep in their own bedroom, and to have more night awakenings. It was also observed a positive association between sleep characteristics evaluated in early infancy and in preschool ages, namely wake-up time (Bˆ =0.288; p<0.001), location of nighttime sleep (Bˆ =0.916; p<0.001) and night awakenings (Bˆ =0.134; p<0.001). Children that at six months of age woke-up later, slept in other person's bedroom and had higher frequency of night awakenings tended to maintain the same characteristics at four years of age. Similarly, later bedtime at six months of age was associated with higher score in the factor for sleep patterns at four years of age (Bˆ =0.236; p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

Estimates of regression coefficients (Bˆ and factor loadings (r) for sleep pattern at four years of age and association with sleep characteristics at six months of age. X2 (18)=30.065; p=0.0368; N=1092; X2/df=1.67; CIF=0.959; TLI=0.938; RMSEA=0.025; WRMR=0.894. All regression coefficients (Bˆ) and factor loadings (r) are p<0.001.

In this study, two distinct sleep patterns were identified during the first four years of age, which were mainly characterized by earlier and later bedtime and wake-up time. Furthermore, sleep characteristics at six months were strongly associated with sleep characteristics at four years of age, with the majority of children maintaining them during this period of time.

Overall, we found that Portuguese children have later sleep and wake up times than children in other countries, namely from United States of America17 and United Kingdom.18 However, our results are in accordance to previous research conducted in other Mediterranean countries,19 which may be related with the influence of familial, environmental and cultural factors on children's sleep habits.1 Additionally, almost a fifth of the Portuguese six months old children sleep in their bedroom, which is a higher than those found in China,20 and lower than the reported percentages in other developed countries.21 As previously observed,20,21 in our study a decrease in the occurrence of night awakenings was also reported by parents as children were getting older.

Regarding the two childhood sleep patterns identified in our study, they seem to correspond to the usual evening or morning types that are well defined in adulthood circadian preference.22 In fact, while in the pattern 1 children are more likely to present earlier bed and wake-up times, in the pattern 2 children go to bed and wake-up at later hours. The early identification of a circadian preference is a relevant finding, as we know that independently of the biological predisposition of some types of circadian rhythms, the environment has an important role in its development.23 In addition, as previously stated, a circadian evening preference might be associated with sleep deprivation, influencing school performance, risk behaviors and health related outcomes during adolescence and adulthood.24

Concerning specifically the influence of marital status, in our study, children whose mothers changed from partnered to not partnered during the first four years after birth are the ones who presented more often an “evening pattern”. In fact, single-parent family structure has been reported to influence negatively the sleep quality at younger ages,25 and, therefore, we may assume that children with a non-partnered mother may be more likely to present poor sleep habits including later bedtime and wake-up time. Moreover, it was interesting to observe higher odds of having pattern 2 among those that changed their family structure during childhood, which may reflect the influence on sleep of a disruptive event as a parental separation of divorce. Nevertheless, the small sample size of these categories precludes the achievement of more robust conclusions on this topic. Furthermore, the association observed in the present study between having siblings and a lower probability of having an “evening pattern”, was expected since houses with more children tend to have stablished rules, possibly reflecting a higher degree of parental control and discipline that may encourage early bedtimes and rising times.26 With regards to the daytime caregiver, we observed that children in the kindergarten were less likely to be classified with pattern 2, which is also plausible. A child that has to move from their house to another place early in the morning has forcibly to wake up earlier, also presenting more stable routines, than the ones who stay at home, which will, consequently, produce an increase on the sleep pressure and a tendency to fall asleep earlier too.27

Our study also showed an association between sleep characteristics at six months and at four years of age. In addition, we found an aggregating factor of sleep characteristics at four years old but not at six months of age; this could be due to the ongoing maturation process that characterizes infancy, with wake and sleep episodes being distributed across day and night, which can have hampered parents’ reports concerning sleep habits. Furthermore, bedtime was the only sleep feature at six months associated with the aggregating sleep pattern at four years, which reflects all evaluated sleep characteristics. One possible explanation for this finding is that this habit is mainly determined by parental control over sleep behavior, which is one of the most important determinants of children's sleep.8 This fact is reinforced with our results, since one of the most important variable to distinguish “morning” from “evening” patterns was also bedtime. Nevertheless, it is also important to refer that in open questions related with time, including asking bedtime or wake-up time hours, digit preference should also be considered, and the variability regarding bedtime hour may underlie a desirability bias.

The results of the present study suggest that it is crucial to initiate and maintain healthy sleep practices during the first months after birth. In fact, sleep disturbances occurring early in life have several health consequences and, even if sleep behaviors are improved later in life, insufficient sleep during infancy may have a deleterious impact on developmental outcomes.28 In fact, poor sleep affects multiple aspects of human development, including physical, cognitive and socioemotional domains,29 being also related with problems with the immune system,30 as well as anxiety and depression,31 which may have severe implications on children's health, learning process, behavior and overall well-being. These consequences are not restricted to childhood, but may also be observed in adolescent and adults, including poor school performance and behavior problems, as well as higher prevalence of hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular diseases, weight gain, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes.5

The major strengths this work are the following: it is based on a large sample of children from a Portuguese birth cohort where a range of sleep characteristics, including bedtime and wake-up time, afternoon naps, locale of nighttime sleep and nighttime awakenings, which were evaluated in two different moments during childhood (at 6 months and at 4 years of age). The inclusion of these variables in the models allowed the identification of two distinct and innovative sleep patterns in childhood, since it was possible to observe an early tendency to circadian preferences, with a strong association between sleep characteristics in early infancy and preschool period.

However, some limitations should be highlighted. Sleep characteristics were evaluated by parental report and without any complementary objective measures, such as actigraphy or polysomnography. Nevertheless, due to the practical difficulties of using objective measurements in large population-based studies, structured questionnaires application has been largely used, and is demonstrated to be a good method for assessing children's sleep habits.32 In addition, the small sample size in some categories of sociodemographic variables, may have precluded the achievement of more robust conclusions. Nonetheless, with a larger sample size we may expected that the magnitude of differences could be distinct, but the observed direction will be the same. Finally, it is well known that in the first months of life, wake and sleep episodes are distributed throughout day and night, while, with increasing age, sleep pattern shifts to a monophasic pattern. Therefore, future studies should also evaluate the number of sleep periods during the day, wake-up time at night, or mid-sleep point, for a specific assessment of differences in circadian preferences in this period of life.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, sleep patterns and a circadian sleep preference seem to develop very early in life. This highlights the large scope of this finding in educational and clinical setting, allowing to deal and intervene at an early stage of the children's development, with the aims of promoting an adequate sleep hygiene and to contribute to a better sleep quality and health outcomes, during the life course.

Availability of databases and material for replicationThe data that support the findings of this study were from Generation XXI birth cohort. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available with the permission of the team responsible for the Generation XXI, which is led by Professor Henrique Barros, upon reasonable request.

Circadian preference seems to be stable across the life span and sleep-wake patterns are established early in life. These patterns are influenced by the interaction of a wide range of intrinsic and extrinsic factors.

What does this study add to the literature?At early childhood, two sleep patterns were found, characterized by earlier and later bedtime and wake-up times, and were in influenced by maternal marital status, siblings and daytime caregiver.

What are the implications of the results?It is crucial to deal and intervene at an early stage of the children's development, aiming to promote an adequate sleep hygiene and to contribute to a better sleep quality during the life course.

J. Jaime Miranda.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsM. Gonçalves collaborated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, has written the draft of the article and approved the final manuscript as submitted. A. Rute Costa collaborated in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, has written the draft of the article and approved the final manuscript as submitted. M. Severo collaborated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed the article critically and approved the final manuscript as submitted. A. Henriques collaborated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, reviewed and revised the article critically for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript as submitted. H. Barros designed the study, collaborated in the analysis and interpretation of the data and reviewed the article critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

AcknowledgementsThe authors gratefully acknowledge the families enrolled in Generation XXI for their kindness, all members of the research team for their enthusiasm and perseverance and the participating hospitals and their staff for their help and support.

FundingThis study was funded by national funding from the Foundation for Science and Technology – FCT (Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education), under the projects UIDB/04750/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020. Generation XXI was funded by Programa Operational de Saúde – Saúde XXI, Quadro Comunitário de Apoio III, Administração Regional de Saúde Norte (Regional Department of Ministry of Health), and Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. It is also acknowledged one Scientific Employment Stimulus contract to AH (CEECIND/01793/2017).

Conflicts of interestNone.