The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoThe aim of this study is to describe the risk factors of anemia among pregnant women.

MethodWe used an observational analytic study with a matched case-control study design. The sampling method used in this study is a simple random sampling technique. The sample size in this study is 138 samples that consist of 46 cases and 92 controls. The data obtained from patient medical records and analyzed statistically using the chi-square test.

ResultsNutritional status is a risk factor of anemia among pregnant women in Community Health Center (Puskesmas) Singgani and Puskesmas Tipo. The risk of pregnant women with chronic energy deficiency (CED) developing anemia is higher in Puskesmas Singgani compared to in Puskesmas Tipo.

ConclusionPrevention can be done by counseling the bride and groom about pregnancy preparation and counseling the pregnant women to pay attention to the nutritional intake, particularly the consumption of folic acid supplements and iron.

Anemia in pregnancy is a condition that hemoglobin (Hb) level in blood is less than 11.0gr% as a result of the inability of red blood cell production to maintain normal Hb concentration levels.1 Anemia in pregnancy is defined as a hemoglobin level of the motherless than 11.0gr% during the first trimester or hemoglobin level lower than 10.5gr% during the second and third trimester.2,3

World Health Organization (WHO) reported the worldwide prevalence of anemia in pregnant women is 40% in 2016.4 In Indonesia, based on RISKESDAS 2018, the prevalence of anemia among pregnant women remains as high as 48.9% or nearly half of the pregnant women population in Indonesia have anemia. This number is higher compared to the amount in 2013 of 37.1%. The highest proportion of anemia among pregnant women is in the age of 15–24 years old, which is 84.6%, 33.7% with the age of 25–34 years old, 33.6% with the age of 35–44 years old, and 24% in pregnant women with the age of 45–54 years old.5 The proportion of anemia pregnant women in Central Sulawesi, especially Palu in 2016, showed that anemia in pregnant women reached 19.52%, an increase of 7.52% when compared to 2015 of 12%.6,7

Pregnant women who are anemic can be at risk of increased mortality and morbidity in both the mother and the baby.8 Anemic pregnant women can be at risk of abortion, preterm labor, premature rupture of membranes, postpartum hemorrhage, and maternal death. Infants with an anemic mother may be at risk for low birth weight, birth defects, perinatal death, and low infant intelligence. The several causes of anemia in pregnancy are iron deficiency, infection, folic acid deficiency, and hemoglobin abnormalities.2,5,9,10

Material and methodWe used an observational analytic study with a matched case-control study design. The dependent variable of this study is the anemia status, while the independent variable is the factors that are thought to be affecting the incidence of anemia in pregnant women, which are oxytocin massage and breast care. The sampling method used in this study is a simple random sampling technique. The sample size in this study is 138 samples consisting of 46 cases and 92 control. The data obtained from patient medical records and analyzed statistically using the chi-square test using SPSS software application version 22.11

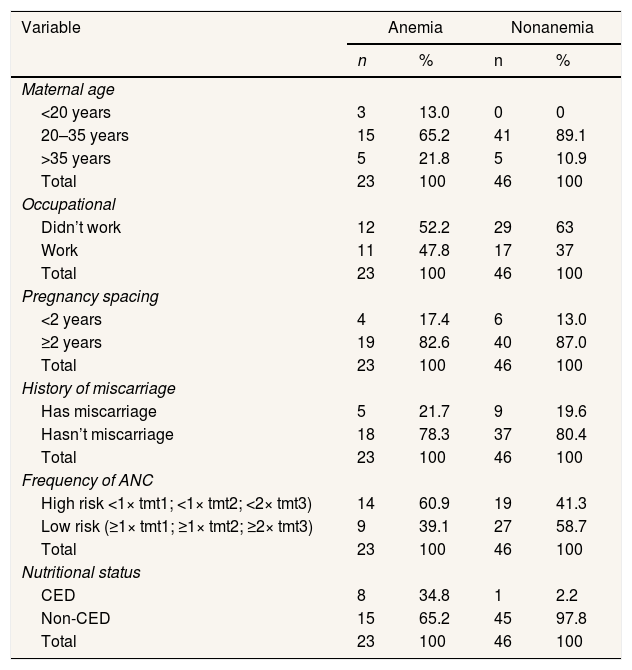

ResultsSample characteristicsDistribution of the sample characteristics of pregnant women in the Singgani health center includes maternal age, occupational status, pregnancy spacing, history of miscarriage, frequency of antenatal care, and nutritional status can be seen in Table 1.

Sample characteristic pregnant women in the singgani health center.

| Variable | Anemia | Nonanemia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Maternal age | ||||

| <20 years | 3 | 13.0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–35 years | 15 | 65.2 | 41 | 89.1 |

| >35 years | 5 | 21.8 | 5 | 10.9 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Occupational | ||||

| Didn’t work | 12 | 52.2 | 29 | 63 |

| Work | 11 | 47.8 | 17 | 37 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Pregnancy spacing | ||||

| <2 years | 4 | 17.4 | 6 | 13.0 |

| ≥2 years | 19 | 82.6 | 40 | 87.0 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| History of miscarriage | ||||

| Has miscarriage | 5 | 21.7 | 9 | 19.6 |

| Hasn’t miscarriage | 18 | 78.3 | 37 | 80.4 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Frequency of ANC | ||||

| High risk <1× tmt1; <1× tmt2; <2× tmt3) | 14 | 60.9 | 19 | 41.3 |

| Low risk (≥1× tmt1; ≥1× tmt2; ≥2× tmt3) | 9 | 39.1 | 27 | 58.7 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Nutritional status | ||||

| CED | 8 | 34.8 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Non-CED | 15 | 65.2 | 45 | 97.8 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

Based on Table 1, it is known that the proportion of mothers with age less than 20 years old only exists in 13.0% of the case group while in the control group, there is none. Then, the maternal age of more than 35 years old is more in the case group, which is 21.8% compared to the control group is 10.9%. While mothers with the age of 20–35 years old in the case group are 60.9%, and the control group is 89.1%. The proportion of mothers who did not work in the case group was 52.2%, and the control group was 63%.

Most of the pregnancy spacing ≥2 years were 19 samples (82.6%) in the case group and 40 samples (87%) in the control group. The proportion of miscarriage history in the case group and the control group is similar in which there is a lot more expectant mother with no history of a miscarriage of 80.4% in the control group and 78.3% in the case group. The proportion of the frequency of high-risk pregnancy examinations is the majority in the case group at 60.9% compared to the control group at 41.3%. The proportion of mothers with CED nutritional status in the case group was 34.8%. This number is higher when compared to the control group, which is only 2.2%.

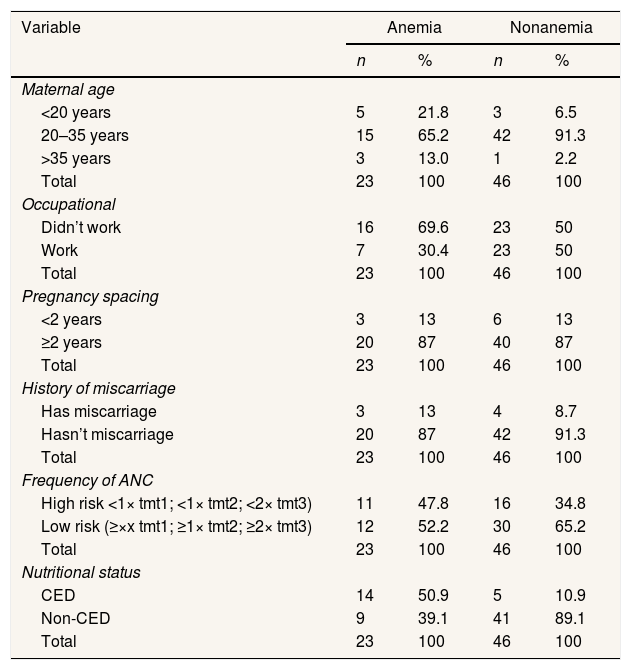

Based on Table 2, it can be seen that the proportion of mothers with the age of fewer than 20 years old in the case group is 21.8%, while in the control group, 6.5%. The mother with the age of more than 35 years old is more in the case group, which is 13.0% compared to the control group, which is 2.2%. While mothers with the age of 20–35 years in the case group are 65.2% and the control group 91.3%.

Sample characteristic pregnant women in Tipo Health Center.

| Variable | Anemia | Nonanemia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Maternal age | ||||

| <20 years | 5 | 21.8 | 3 | 6.5 |

| 20–35 years | 15 | 65.2 | 42 | 91.3 |

| >35 years | 3 | 13.0 | 1 | 2.2 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Occupational | ||||

| Didn’t work | 16 | 69.6 | 23 | 50 |

| Work | 7 | 30.4 | 23 | 50 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Pregnancy spacing | ||||

| <2 years | 3 | 13 | 6 | 13 |

| ≥2 years | 20 | 87 | 40 | 87 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| History of miscarriage | ||||

| Has miscarriage | 3 | 13 | 4 | 8.7 |

| Hasn’t miscarriage | 20 | 87 | 42 | 91.3 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Frequency of ANC | ||||

| High risk <1× tmt1; <1× tmt2; <2× tmt3) | 11 | 47.8 | 16 | 34.8 |

| Low risk (≥×x tmt1; ≥1× tmt2; ≥2× tmt3) | 12 | 52.2 | 30 | 65.2 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

| Nutritional status | ||||

| CED | 14 | 50.9 | 5 | 10.9 |

| Non-CED | 9 | 39.1 | 41 | 89.1 |

| Total | 23 | 100 | 46 | 100 |

The proportion of mothers who did not work in the case group was 69.6%, and the control group was 50%. The most common pregnancy spacing in the case group and the control group is the low-risk pregnancy spacing (87%). The proportion of frequency of antenatal care in the case group was more low risk, which was 52.2%. Similarly, the control group was more low risk at 65.2%. The proportion of case groups with CED nutritional status was 52.2%. This number is greater when compared to the control group, which is only 10.9%.

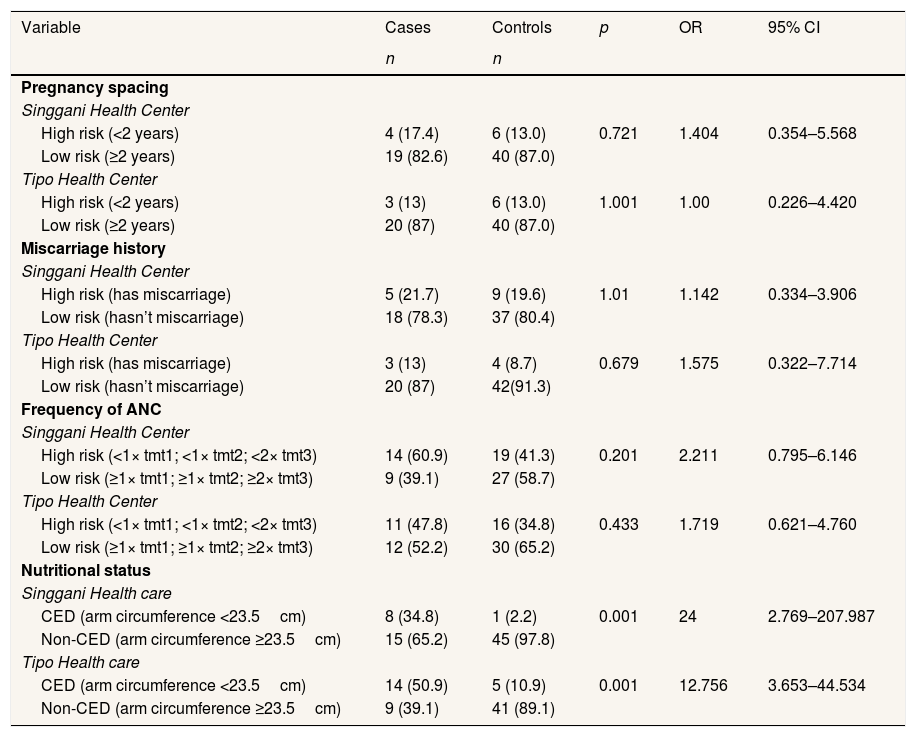

Bivariate analysis of risk factors for anemia among pregnant women in Community Health Center (Puskesmas) Singgani and Puskesmas TipoRisks of each variable in this study can be seen in the following table.

Based on Table 3, the statistical test results of pregnancy spacing variables at the Puskesmas Singgani obtained an OR value of 1.404, but this was not significant because the 95% CI range included one (95% CI=0.354–5.568). Statistical test results of pregnancy spacing at Puskesmas Tipo obtained OR values of 1.00. It is also not significant because the 95% CI range includes one (95% CI=0.226–4.420).

Bivariate analysis of risk factors for anemia among pregnant women in Puskesmas Singgani and Puskesmas Tipo.

| Variable | Cases | Controls | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | ||||

| Pregnancy spacing | |||||

| Singgani Health Center | |||||

| High risk (<2 years) | 4 (17.4) | 6 (13.0) | 0.721 | 1.404 | 0.354–5.568 |

| Low risk (≥2 years) | 19 (82.6) | 40 (87.0) | |||

| Tipo Health Center | |||||

| High risk (<2 years) | 3 (13) | 6 (13.0) | 1.001 | 1.00 | 0.226–4.420 |

| Low risk (≥2 years) | 20 (87) | 40 (87.0) | |||

| Miscarriage history | |||||

| Singgani Health Center | |||||

| High risk (has miscarriage) | 5 (21.7) | 9 (19.6) | 1.01 | 1.142 | 0.334–3.906 |

| Low risk (hasn’t miscarriage) | 18 (78.3) | 37 (80.4) | |||

| Tipo Health Center | |||||

| High risk (has miscarriage) | 3 (13) | 4 (8.7) | 0.679 | 1.575 | 0.322–7.714 |

| Low risk (hasn’t miscarriage) | 20 (87) | 42(91.3) | |||

| Frequency of ANC | |||||

| Singgani Health Center | |||||

| High risk (<1× tmt1; <1× tmt2; <2× tmt3) | 14 (60.9) | 19 (41.3) | 0.201 | 2.211 | 0.795–6.146 |

| Low risk (≥1× tmt1; ≥1× tmt2; ≥2× tmt3) | 9 (39.1) | 27 (58.7) | |||

| Tipo Health Center | |||||

| High risk (<1× tmt1; <1× tmt2; <2× tmt3) | 11 (47.8) | 16 (34.8) | 0.433 | 1.719 | 0.621–4.760 |

| Low risk (≥1× tmt1; ≥1× tmt2; ≥2× tmt3) | 12 (52.2) | 30 (65.2) | |||

| Nutritional status | |||||

| Singgani Health care | |||||

| CED (arm circumference <23.5cm) | 8 (34.8) | 1 (2.2) | 0.001 | 24 | 2.769–207.987 |

| Non-CED (arm circumference ≥23.5cm) | 15 (65.2) | 45 (97.8) | |||

| Tipo Health care | |||||

| CED (arm circumference <23.5cm) | 14 (50.9) | 5 (10.9) | 0.001 | 12.756 | 3.653–44.534 |

| Non-CED (arm circumference ≥23.5cm) | 9 (39.1) | 41 (89.1) | |||

Statistical test results of miscarriage history at the Puskesmas Singgani obtained an OR value of 1.142, but this is not significant because the 95% CI range includes one (95% CI=0.334–3.906). Statistical test results of miscarriage history at Puskesmas Tipo obtained OR values of 1.575. This is also not significant because the 95% CI range includes one (95% CI=0.322–7.714).

Statistical test results of the frequency of antenatal care variables at Puskesmas Singgani obtained an OR value of 2.211, but this was not significant because the 95% CI range included one (95% CI=0.795–6.146). Statistical test results on the frequency of antenatal care at the Puskesmas Tipo obtained an OR value of 1.719. It is also not significant because the 95% CI range includes one (95% CI=0.621–4.760).

Statistical test results of nutritional status variables at Puskesmas Singgani obtained an OR value of 24, which means that the nutritional status variable is a risk factor because the OR value is more than one. This is significant because the 95% CI value range does not include the number one (95% CI=2.769–207.987). Pregnant women with chronic energy deficiency (CED) are at risk of anemia by 24 times. The statistical test results of nutritional status variables at Puskesmas Tipo obtained an OR value of 12.75, which means that the nutritional status variable is a risk factor because the OR value is more than one. This is also significant because the 95% CI value range does not include the number one (95% CI=3.653–44.534), so it can be concluded that expectant mothers with chronic energy deficiency are at risk of 12.75 times developing anemia in their pregnancy later on.

DiscussionAnalysis of risk factors of anemia among pregnant women in Puskesmas Singgani and Puskesmas TipoPregnant women with pregnancy spacing that is too close, which is less than two years, are at risk of anemia because the mother's body has not reserved adequate nutrients after going through the previous pregnancy so that the iron in her body is divided for recovery of her body and to fulfill the needs during the next pregnancy.12 It takes a minimum of 2 years to restore iron reserves to normal on the condition of consuming foods that contain protein and iron. This period also allows the body to restore its physiological and anatomical functions. But in this study, there was no significant effect between pregnancy spacing and the incidence of anemia in pregnant women. This is because both the case and control groups mostly have a pregnancy interval of more than 2 years.13,14

Based on the bivariate test results, it is known that the pregnancy spacing is not a risk factor for anemia among pregnant women in Puskesmas Singgani and Puskesmas Tipo. The results of this study are in line with the research conducted by Tanziha et al. (2017) in Indonesia. From the results of the previous study, the author obtained a value of 95% CI, includes the number 1, which means there is no relationship between the pregnancy spacing with the incidence of anemia in pregnant women.15 Another study conducted by Anggraini et al. (2018) at Tanjung Pinang Health Center showed that pregnancy spacing increased the risk of anemia by 15,483 times.16 Likewise, the results of the study of Getahun et al. in South Ethiopia with the results showing a pregnancy spacing ≥2 years are a protective factor of anemia among pregnant women.13,17

A history of miscarriage can increase the risk of anemia in subsequent pregnancies due to an increase in previous blood loss, thereby decreasing iron reserves in the body. Statistical test results showed that a history of miscarriage is not a risk factor for anemia among pregnant women at the Puskesmas Singgani and Tipo. A history of miscarriage was previously investigated by Berhe et al. (2019) in Northern Ethiopia; from the results of the study found that pregnant women with a history of miscarriage have a 7.9 times risk of anemia in subsequent pregnancies compared with those who have never miscarried.18,19

Pregnancy examination or antenatal care is an examination given to expectant women by health workers during their pregnancy, with a standard number of visits during pregnancy at least four times, including history taking, general physical and obstetric examination, laboratory examinations for certain indications as well as basic and special indications. An examination of the pregnancy carried out early will allow the discovery of abnormalities or health problems faced by the mother during the process of pregnancy, so that any measures can be taken to save the fetus and the mother.

The ANC service standard includes the number of visits and the type of inspection carried out. ANC is done at least four times during pregnancy, namely once in the first trimester, once in the second trimester, and at least twice in the third trimester. The type of examination consists of 7T, namely weight checking, blood pressure measurement, checking the height of the fundus uteri, giving TT immunization, administering supplemental iron tablets, testing for sexually transmitted disease, and colloquium in the context of referral preparation. Routine pregnancy examination can reduce the risk of anemia in pregnant women because it can be detected as early as possible and also given iron tablets at each visit.

Statistical test results showed that the frequency of antenatal care is not a risk factor for anemia in pregnancy at the Puskesmas Singgani and Tipo. The results of this study are in line with a study conducted by Tanziha et al. (2017), where there is no relationship between antenatal care or ANC with the incidence of anemia in pregnant women.15 The results of this study differ from studies conducted by Singal et al. (2018) in India with the results obtained p-value=0.001, which means there is a relationship between lack of antenatal care (ANC) examination with the incidence of anemia in pregnant women.20,21

During physiological pregnancy, changes occur, one of which is an increase in the volume of fluid and red blood cells and a decrease in the concentration of protein binding nutrients in the blood circulation, as well as a decrease in micronutrients. Pregnancy is a period of growth and development of the fetus towards birth so that nutritional disorders that occur during pregnancy will have a major impact on the health of the mother and fetus. Therefore chronic energy deficiency status (CED) in pregnant women can have an impact on the incidence of anemia in pregnant women as well as the incidence of low birth weight (LBW) and stunting.9

Based on the bivariate test results, it is known that nutritional status is a risk factor for anemia among pregnant women at the Puskesmas Singgani and Puskesmas Tipo. Pregnant women with chronic energy deficiency conditions at the Puskesmas Singgani are 24 times at risk of anemia compared to pregnant women who do not experience CED. Whereas pregnant women who developed CED in Puskesmas Tipo have a risk of 12.75 times are developing anemia in their pregnancy. This is reinforced by the results of previous studies conducted by Lestari et al. (2018) in Medan, North Sumatra, where there is an association between chronic energy deficiency with the incidence of anemia in pregnancy.22 The same results were obtained from the study of Tekeste et al. (2015) with a large risk of developing anemia by 2.52 times.23

Chronic energy deficiency (CED) is a condition of the body that lacks macronutrients (carbohydrates, protein, and fat) for a long period of time, characterized by the size of the upper arm circumference of less than 23.5cm. Macronutrient deficiencies are associated with micronutrient deficiencies, especially vitamin A, vitamin D, folic acid, iron, zinc, calcium, and iodine. The condition of a pregnant with CED can cause anemia in her pregnancy.24 Nutritional status is a risk factor of anemia among pregnant women in Puskesmas Singgani and Puskesmas Tipo. It happens because nutritional status is a factor that plays a direct role in the nutritional needs of pregnant women and their fetuses so that the lack of nutritional intake in pregnant women with CED can cause anemia in pregnancy. The risk of pregnant women with CED to develop anemia in the Puskesmas Singgani is higher than the Puskesmas Tipo. This is influenced by the diet of pregnant women, especially food sources of iron, and adherence to the consumption of supplemental iron tablets during pregnancy.

ConclusionThe results of this study are nutritional status is a risk factor for anemia among pregnant women in Puskesmas Singgani and Tipo. We expected that midwives would work closely with active kader posyandu in screening pregnant women with anemia, especially with chronic energy deficiency conditions. Prevention can be done by counseling the bride and groom about pregnancy preparation and counseling the pregnant women to pay attention to the nutritional intake, particularly the consumption of folic acid supplements and iron.

The authors would like to thank the Dean and the all vice-dean, the Faculty of Public Health at Hasanuddin University, for the research funding.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.