The late Barbara Starfield, the field's intellectual giant, and colleagues have provided the most important empirical work and review of the literature in relation to the impact of primary care on health systems. Studies conducted in different countries and time periods find strong associations between the strength of primary care and different outcome measures such as health status, satisfaction and lower health expenditures.1 Despite the fact that reviews are not always systematic, that most studies are observational and that controlling for confounding variables is not always possible, the favorable results for primary care are consistent over different countries and years. In more specific studies that try to find the impact of primary care physician supply on health status controlling for the endogeneity of primary care physician supply we find both a favorable result in the UK2 and a non significant effect in Norway.3

In any case, as Friedberg4 et al.4 mention, observed associations between high primary care physicians to specialty ratios, better health care and lower costs may not mean that primary care physicians provide better care than specialists. The quality of the health system is not simply the addition of the quality of its components: general practitioners and specialists behavior influence each other. General practitioners in highest spending regions of the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care were significantly more likely than those in the lowest regions to report more aggressive use of discretionary tests, visits and interventions. System-level characteristics, specifically a primary care orientation, matter more than the number of general practitioners.5

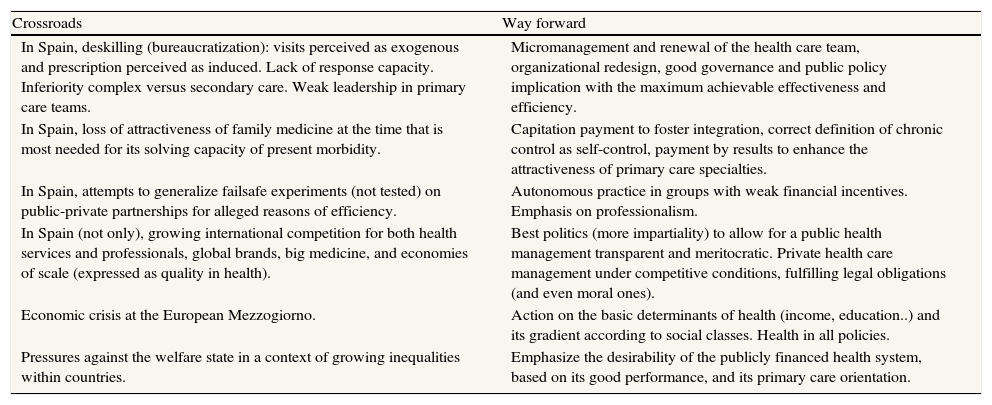

Table 1 summarizes each of the six crossroads considered in this article and its way forward. The first four, which specifically refer to Spain are analyzed, respectively, in the next four sections.

Primary care at the crossroads.

| Crossroads | Way forward |

| In Spain, deskilling (bureaucratization): visits perceived as exogenous and prescription perceived as induced. Lack of response capacity. Inferiority complex versus secondary care. Weak leadership in primary care teams. | Micromanagement and renewal of the health care team, organizational redesign, good governance and public policy implication with the maximum achievable effectiveness and efficiency. |

| In Spain, loss of attractiveness of family medicine at the time that is most needed for its solving capacity of present morbidity. | Capitation payment to foster integration, correct definition of chronic control as self-control, payment by results to enhance the attractiveness of primary care specialties. |

| In Spain, attempts to generalize failsafe experiments (not tested) on public-private partnerships for alleged reasons of efficiency. | Autonomous practice in groups with weak financial incentives. Emphasis on professionalism. |

| In Spain (not only), growing international competition for both health services and professionals, global brands, big medicine, and economies of scale (expressed as quality in health). | Best politics (more impartiality) to allow for a public health management transparent and meritocratic. Private health care management under competitive conditions, fulfilling legal obligations (and even moral ones). |

| Economic crisis at the European Mezzogiorno. | Action on the basic determinants of health (income, education..) and its gradient according to social classes. Health in all policies. |

| Pressures against the welfare state in a context of growing inequalities within countries. | Emphasize the desirability of the publicly financed health system, based on its good performance, and its primary care orientation. |

A Cochrane Review on substitution of doctors by nurses in PHC concludes the following: patient health outcomes were similar for nurses and doctors but patient satisfaction was higher with nursing-led care. Nurses tended to provide longer consultation, give more information to patients and recall patients more frequently that did doctors.6

Economies of scale, scope and learning tend to drive organizations towards larger sizes. Firms become oligopolies and the state should intervene to avoid its most deleterious effects. Big medicine is also coming to health care. And for the changes to live up to our hopes (lower costs and better care for everyone), as Atul Gawande says, a trade-off will have to be found between the acceptance of the growth of such big medicine and the need for a stronger public oversight of health systems.7

Despite the fact that scale economies are not important in primary care and that, what is already happening in Narayana Hrudayalaya in Bangalore (or in the Aravind Eye Care System or in Life Spring hospitals also in India) has no immediate translation in primary care, there is one driving force in the division of labor: specialization up to the point where the advantages of further specialization don’t compensate anymore for the increasing costs of coordination. Besides specialization it is important that tasks shall be assigned according to the qualification and training required: the most complex intervention to the better qualified personnel, everything else to other professionals. Similar to Aravind: one surgeon in an operating theatre with two beds and six eye-care technicians, at least, for every surgeon.

Years of excess medical underemployment in some countries and sheer power in others have led to a medical practice style where many functions can be performed equally well or better by other professionals. Doctors lobbies would resist, or limit, task shifting. When the Institute of Medicine issued a report that called for nurses to play a greater role in primary care, the American Medical Association's comment was: ‘Nurses are critical to the health care team, but there is no substitute for education and training’.8 In Spain, the Supreme Court has issued a verdict, ratifying a previous judgment, against the complaint filed by the Spanish Medical Association (Organización Médica Colegial), recognizing the ability to prescribe drugs by nurses with the Family and Community Nursing specialization.9

General practitioners tasks shall be completely revised: administrative activities performed outside consultations, question and share with other professionals all self-generated activities (primarily chronic controls), including the definition of chronically ill (no control without self-control), intense nursing involvement in assisting with acute diseases. Experiences like CASAP, Castelldefels-Spain, where assistance is shared between doctors and nurses seem to offer good results. General practitioners should focus on what they do best, demanding tasks justifying their training and experience, leaving much of what they currently do to other professionals.

Paying for what mattersWhat matters is health not health expenditure.10 A Swiss experiment shows that both physicians and consumers want significant compensation to embrace coordinated or integrated care.11 General practitioners will require a pay increase of up to 40% before they are willing to embrace certain aspects of coordinated care. The study also found that such an increase in compensation to physicians could be financed through savings generated by coordinated care. However, those savings would probably not be sufficient to support the additional compensation necessary to induce the average Swiss consumer to sign up for a coordinated care plan.

Health personnel salaries are ultimately determined by supply and demand, which does not mean that the health regulator is satisfied with the dictum of the market. You can expect little appreciation of ‘wait and see’, little appreciation of the chair as ‘diagnostic tool’ (Marañón), and, at the same time uncritical fascination with technology. Hence, it is not unreasonable to ask for the adjustment of some of these market valuations (salaries of specialists, for example) when it comes to ensuring access according to need. It's not about private whims borne by an individual demand up to whatever their pocket allows. It's about keeping a collective will to pay for health services, which demands to be aware of both their relative effectiveness and their costs.. and to try to act on those costs when severely distorted. Hsiao focused on stress variables (time, mental effort, knowledge, clinical judgment, technical skill, physical effort and psychological stress) to propose a relative valuation of specialties. Today we would focus more on outcome variables keeping intermediate results currently available, with minimal adjustments, mainly for social class, as a measure of performance.12

Reshaping the PHC consultation is health system contingentIn Spain13:

- •

Utilization management by streamlining the content of the consultations, eliminating the useless, which is non negligible, and redirecting the useful (to other professionals, new technologies) has an impact on the frequentation, freeing up time to act on other limitations

- •

Clear assumption of the role of patient's health agent to avoid induced prescribing, managing the patient's prescription, without complexes and assuming the difficulties resulting thereof.

The current information systems allow general practitioners to have the information needed to develop a plan of action along these lines and to evaluate the results we are achieving.

Primary care problems: beyond resource shortagePrimary care problems refer more to the distribution of its resources rather than to any shortages.14 Health system integration remains the main challenge. Three axes should guide the renewal response: micromanagement and renewal of the care team, organizational redesign, and perhaps most difficult, good governance and public policy implication with the maximum achievable effectiveness and efficiency (not to be confused with mere savings), and the same standards of transparency, accountability and responsibility required from health professionals. All these should be guided by a sincere concern for relevant results, those affecting the health and satisfaction of users, and -relevant but secondary- the legitimate satisfaction of the professionals with their work.15

Author’ contributionI, Vicente Ortún, confirm that the editorial presented has been performed and interpreted solely by myself and has not been submitted elsewhere.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.