To estimate the prevalence of moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as defined by the World Health Organisation (WHO), and associated factors among teenagers from Barcelona in 2012.

MethodsCross-sectional survey to assess risk factors in a representative sample of secondary school students (aged 13–16 years, International Standard Classification of Education [ISCED] 2, n=2,162; and 17–18 years, ISCED 3, n=1016) in Barcelona. We estimated MVPA prevalence overall, and for each independent variable and each gender. Poisson regression models with robust variance were fit to examine the factors associated with high-level MVPA, and obtained prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

ResultsOnly 13% of ISCED 2 and 10% of ISCED 3 students met the WHO physical activity recommendations. This percentage was lower among girls at both academic levels. MVPA was lower among ISCED 3 compared to ISCED 2 students, and among students with a lower socioeconomic status. Physical activity was associated with positive self-perception of the health status (e.g., positive self-perception of health status among ISCED 2 compared to ISCED 3 students: PR=1.31 [95%CI: 1.22–1.41] and 1.61 [95%CI: 1.44–1.81] for boys and girls, respectively].

ConclusionsThe percentage of teenagers who met WHO MVPA recommendations was low. Strategies are needed to increase MVPA levels, particularly in older girls, and students from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

Estimar la prevalencia de actividad física moderada y vigorosa (AFMV), tal como la define la Organización Mundial de la Salud (OMS), y sus factores asociados en adolescentes de Barcelona en el año 2012.

MétodosEncuesta transversal para evaluar los factores de riesgo en una muestra representativa de estudiantes de secundaria (13-16 años, Clasificación Internacional Normalizada de la Educación [CINE] 2, n=2162; y 17-18 años, CINE 3, n=1016) de Barcelona. Se estimó la prevalencia de la AFMV en general y para cada variable independiente y sexo. Se ajustaron modelos de regresión con varianza robusta para examinar los factores asociados con niveles altos de AFMV, obteniendo razones de prevalencia (RP) y los intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC95%).

ResultadosSolo el 13% de los estudiantes de CINE 2 y el 10% de CINE 3 cumplían con las recomendaciones de actividad física de la OMS. Este porcentaje fue inferior en las chicas en ambos niveles académicos. La AFMV fue menor en los estudiantes de CINE 3 comparados con los de CINE 2, y en aquellos con un nivel socioeconómico más bajo. La actividad física se asoció con una autopercepción positiva del estado de salud (p. ej., autopercepción positiva de la salud en los/las estudiantes de CINE 2, en comparación con los/las de CINE 3: PR=1,31 [IC95%: 1,22-1,41] y 1,61 [IC95%: 1,44-1,81] para chicos y chicas, respectivamente).

ConclusionesEl porcentaje de adolescentes que cumplían con las recomendaciones de AFMV de la OMS fue bajo. Se necesitan estrategias para incrementar la AFMV, en particular en las chicas de mayor edad y en los/las estudiantes con niveles socioeconómicos bajos.

Regular vigorous physical activity contributes to improved general physical health and lower rates of depression and anxiety.1 Research suggests that academic performance is also enhanced in students who regularly engage in physical activity.2 Importantly, from a long-term health perspective, participation in regular physical activity during adolescence is associated with a greater probability of being a physically active adult, a key determinant in preventing a range of negative health outcomes.3

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that children and teenagers aged 5-17 years participate in at least 60minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA) daily. MVPA is associated with more favourable health parameters, such as lower central adiposity, reduced cardiovascular risk and improved bone health.4 However, most studies in teenagers indicate that only a small percentage meet these recommendations. Global estimates suggest that only 20% of teenagers aged 13-15 years achieve recommended levels of MVPA.5 In Europe, this percentage is 34% among 11- to 15-year-olds,6 and just 17% in Spain.7 In 2008, in Barcelona, it is estimated that less than half (44%) of students aged 13 to 19 years regularly participated in physical activity, and there is no information regarding the amount of time spent in physical activity.8

Regular physical activity during adolescence appears to be especially uncommon among girls,9 older teenagers,10 and those with a lower socioeconomic status (SES).11 Lifestyle factors, such as alcohol or tobacco use,12 and some health indicators, such as self-perceived health status, mood or body mass index (BMI),13 have also been found to be related physical activity in teenagers. However, the reported strength and the direction of these associations are often contradictory, possibly because few studies have accounted for important factors such as school and neighbourhood settings, and other factors that may limit physical activity.14,15 Moreover, parents, friends and teachers have an important influence on physical activity, and their support is associated with greater participation in physical activity.16

Given the importance of physical activity for health and wellbeing, and the current climate of poor compliance with recommended levels of physical activity among teenagers, it is important to identify factors associated with failure to achieve MVPA recommendations.4 This would facilitate the design of interventions to address factors that prevent teenagers from achieving recommended MVPA levels. Thus, the aim of our study was to estimate the prevalence of moderate and vigorous physical activity (MVPA), as defined by the WHO, and associated factors among teenagers from Barcelona in 2012.

MethodsA cross-sectional survey of lifestyle risk factors (Risk Factors in Secondary School Students; FRESC) was conducted in a representative sample of secondary school students from Barcelona who had been classified according to the UNESCO International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) as ISCED 2 (13-16 years) and ISCED 3 (17-18 years).17 Students completed an anonymous self-report questionnaire that collected information on various behaviours, such as substance use, leisure time activities, and sedentary behaviour. Anthropometric data based objective measurements of weight and height was also collected.

In Barcelona, in 2011-2012, there were 274 schools, 1,659 classrooms and 40,278 students.18 Stratified random sampling was used for all academic levels, with the classroom as the smallest sampling unit. Stratification was conducted according to type of school (public, private or subsidised) and the SES of the surrounding neighbourhood (low, medium or high, according to the Index of Familial Economic Capacity).19 The students’ response rate was 87.6%. Students who provided incomplete data (9%) were excluded from the study, resulted in a total sample of 3,178 students (ISCED 2, n=2,162; ISCED 3, n=1,016; girls, n=1,643; boys, n=1,535).

The self-reported questionnaire20 was administered between January and March of 2012 by trained personnel from Barcelona Public Health Agency (ASPB) during school time in the presence of the classroom teacher. Principals and teachers of selected schools were properly informed about the objectives of the study and they gave their verbal informed consent. Given the nature of the questionnaire, the Research Committee of the ASPB did not consider necessary a parental informed consent.

The dataset was created by scanning the completed forms using the Teleform 10.2 program.

Dependent variableThe dependent variable was based on answers to the question: “How many hours a day do you spend practising sport? (i.e. physical activity that makes you sweat and become out of breath, such as, football, swimming, etc., including physical activity practised at school)”. We requested a separate response to this open question for each day of the week, which allowed us to assess the daily number of minutes of physical activity. From this we determined whether students had performed more than 60minutes or less than 60minutes of physical activity per day, and constructed three distinct dependent variables:

- •

MVPA3: ≥60minutes of MVPA per day at least 3 days a week;

- •

MVPA5: ≥60minutes of MVPA per day at least 5 days a week;

- •

MVPA7: ≥60minutes of MVPA per day, 7 days a week (the WHO recommendation).

We used three types of independent variables (Table 1):

- •

Socio-demographic variables: academic level (ISCED 2; ISCED 3); migration status (native; 1st generation immigrant, individuals born outside Spain; and 2nd generation immigrant, individuals born in Spain but with at least one parent born outside Spain); type of school (public, private or subsidised); socioeconomic status (SES) of the individual and the school. To obtain individual SES we used the Family Affluence Scale (FAS),7 an individual measure based on the material conditions of households in which young people live, such as holidays or bedroom occupancy. This variable was categorized as low, medium or high individual SES. The SES of the school was established on the basis of the average household income in the surrounding neighbourhood,21 and was categorized in quartiles, with the lowest and highest SES corresponding to the first and fourth quartiles, respectively.

- •

Lifestyles variables: having been drunk (never, ever, or in previous 12 months); regular smoking (smoking at least one cigarette per day, yes or no); regular cannabis use (having consumed cannabis during the previous 30 days, yes or no); screen-related sedentary behaviour (spending ≥2hours per day watching television and/or playing videogames and/or using the computer for activities other than school work, yes or no); self-perceived academic level relative to class mates (low, medium or high); BMI calculated from objective anthropometric measures (underweight, normal weight; overweight; obesity, according to the WHO BMI for age 5-19 years);24 and being on a diet (yes or not).

- •

Health-related variables: negative mood state (responding “often” or “always” to ≥3 of the 6 mood state problems, yes or no); self-perceived health status (good/regular/bad and very good/excellent); mental health, assessed using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (normal: 0 to 15 points, limit 16 to 19 points; or abnormal, 20 to 40 points).22

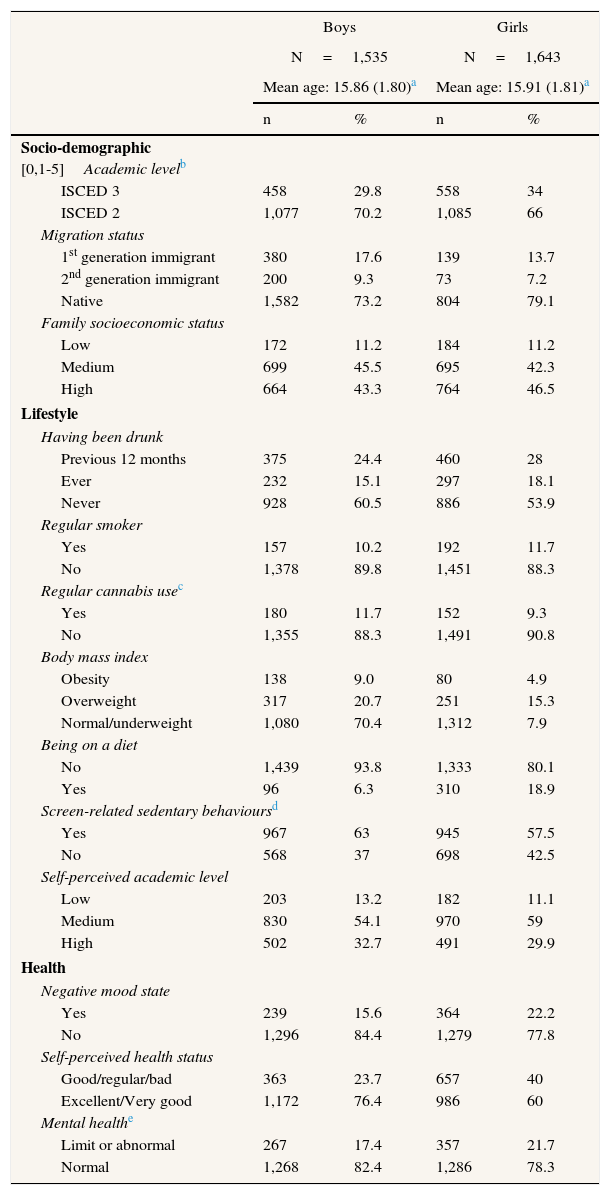

Distribution of the independent variables in the sample by sex.

| Boys | Girls | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=1,535 | N=1,643 | |||

| Mean age: 15.86 (1.80)a | Mean age: 15.91 (1.81)a | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Socio-demographic [0,1-5]Academic levelb | ||||

| ISCED 3 | 458 | 29.8 | 558 | 34 |

| ISCED 2 | 1,077 | 70.2 | 1,085 | 66 |

| Migration status | ||||

| 1st generation immigrant | 380 | 17.6 | 139 | 13.7 |

| 2nd generation immigrant | 200 | 9.3 | 73 | 7.2 |

| Native | 1,582 | 73.2 | 804 | 79.1 |

| Family socioeconomic status | ||||

| Low | 172 | 11.2 | 184 | 11.2 |

| Medium | 699 | 45.5 | 695 | 42.3 |

| High | 664 | 43.3 | 764 | 46.5 |

| Lifestyle | ||||

| Having been drunk | ||||

| Previous 12 months | 375 | 24.4 | 460 | 28 |

| Ever | 232 | 15.1 | 297 | 18.1 |

| Never | 928 | 60.5 | 886 | 53.9 |

| Regular smoker | ||||

| Yes | 157 | 10.2 | 192 | 11.7 |

| No | 1,378 | 89.8 | 1,451 | 88.3 |

| Regular cannabis usec | ||||

| Yes | 180 | 11.7 | 152 | 9.3 |

| No | 1,355 | 88.3 | 1,491 | 90.8 |

| Body mass index | ||||

| Obesity | 138 | 9.0 | 80 | 4.9 |

| Overweight | 317 | 20.7 | 251 | 15.3 |

| Normal/underweight | 1,080 | 70.4 | 1,312 | 7.9 |

| Being on a diet | ||||

| No | 1,439 | 93.8 | 1,333 | 80.1 |

| Yes | 96 | 6.3 | 310 | 18.9 |

| Screen-related sedentary behavioursd | ||||

| Yes | 967 | 63 | 945 | 57.5 |

| No | 568 | 37 | 698 | 42.5 |

| Self-perceived academic level | ||||

| Low | 203 | 13.2 | 182 | 11.1 |

| Medium | 830 | 54.1 | 970 | 59 |

| High | 502 | 32.7 | 491 | 29.9 |

| Health | ||||

| Negative mood state | ||||

| Yes | 239 | 15.6 | 364 | 22.2 |

| No | 1,296 | 84.4 | 1,279 | 77.8 |

| Self-perceived health status | ||||

| Good/regular/bad | 363 | 23.7 | 657 | 40 |

| Excellent/Very good | 1,172 | 76.4 | 986 | 60 |

| Mental healthe | ||||

| Limit or abnormal | 267 | 17.4 | 357 | 21.7 |

| Normal | 1,268 | 82.4 | 1,286 | 78.3 |

All analyses were stratified by sex. A preliminary univariate analysis was conducted to establish the percentage of teenagers who participated in MVPA for ≥1hour on ≥3 (MVPA3), ≥5 (MVPA5), or 7 (MVPA7) days/week, for each sex and academic level. To evaluate which factors were associated with greater levels of MVPA, we fit crude and adjusted Poisson regression models with robust variance, obtaining prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI)23. We used the MVPA3 variable to study associated factors, since there were too few cases of MVPA5 and MVPA7. A sensitivity analysis was also carried out to evaluate the consistency of the result across all three MVPA variables. All analyses were conducted using STATA 13.

ResultsJust under half (48.3%) of the sample were boys, 23.9% were 1st or 2nd generation immigrants, and 88.8% were from a medium or high SES background. Almost one-quarter (24.9%) of students were overweight or obese, 6.3% of boys and 18.9% of girls reported being on diet at the time of the interview, and approximately two-thirds (60.2%) reported screen-related sedentary behaviour (Table 1).

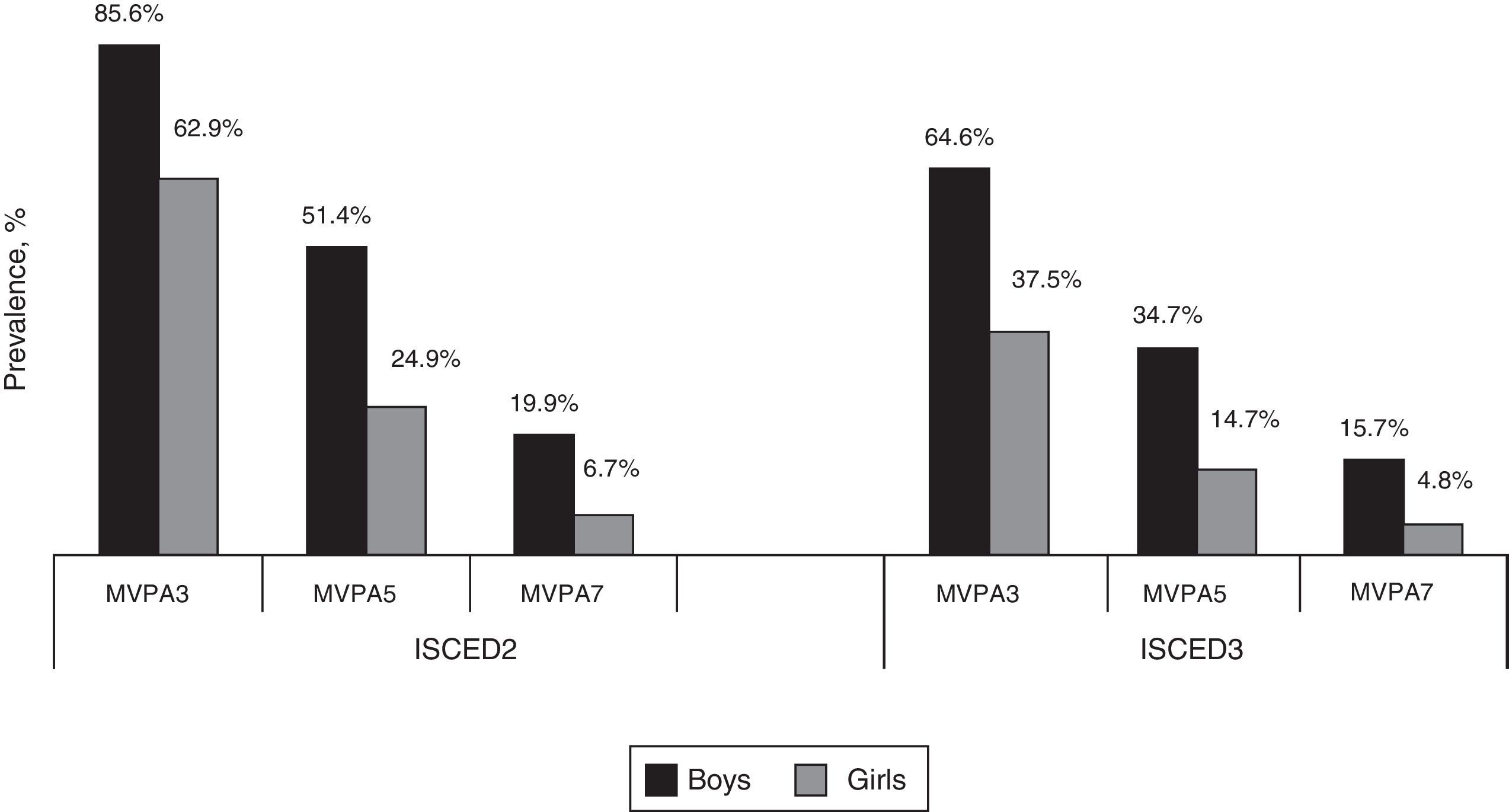

Figure 1 shows the percentage of students that practised MVPA, according to each variable (MVPA3, MVPA5 and MVPA7). In all cases, the percentage of students that practised MVPA was higher among boys than girls and among ISCED 2 students. For example, while 13.3% of all ISCED 2 students reported practising MVPA7, the percentage among boys was 3 times that among girls (20% and 7%, respectively). The percentage of ISCED 3 students who met the recommended levels of activity (MVPA7) was lower (10.3%), but still higher among boys than girls (16% and 5%, respectively).

Prevalence of moderate or vigorous physical activity (MVPA3, ≥1hour/day, 3 days/week; MVPA5, 5 days/week; MVPA7, 7 days/week) among secondary school students in Barcelona, according to academic level and sex. Students’ academic level classified according to the UNESCO International Standard Classification of Education.

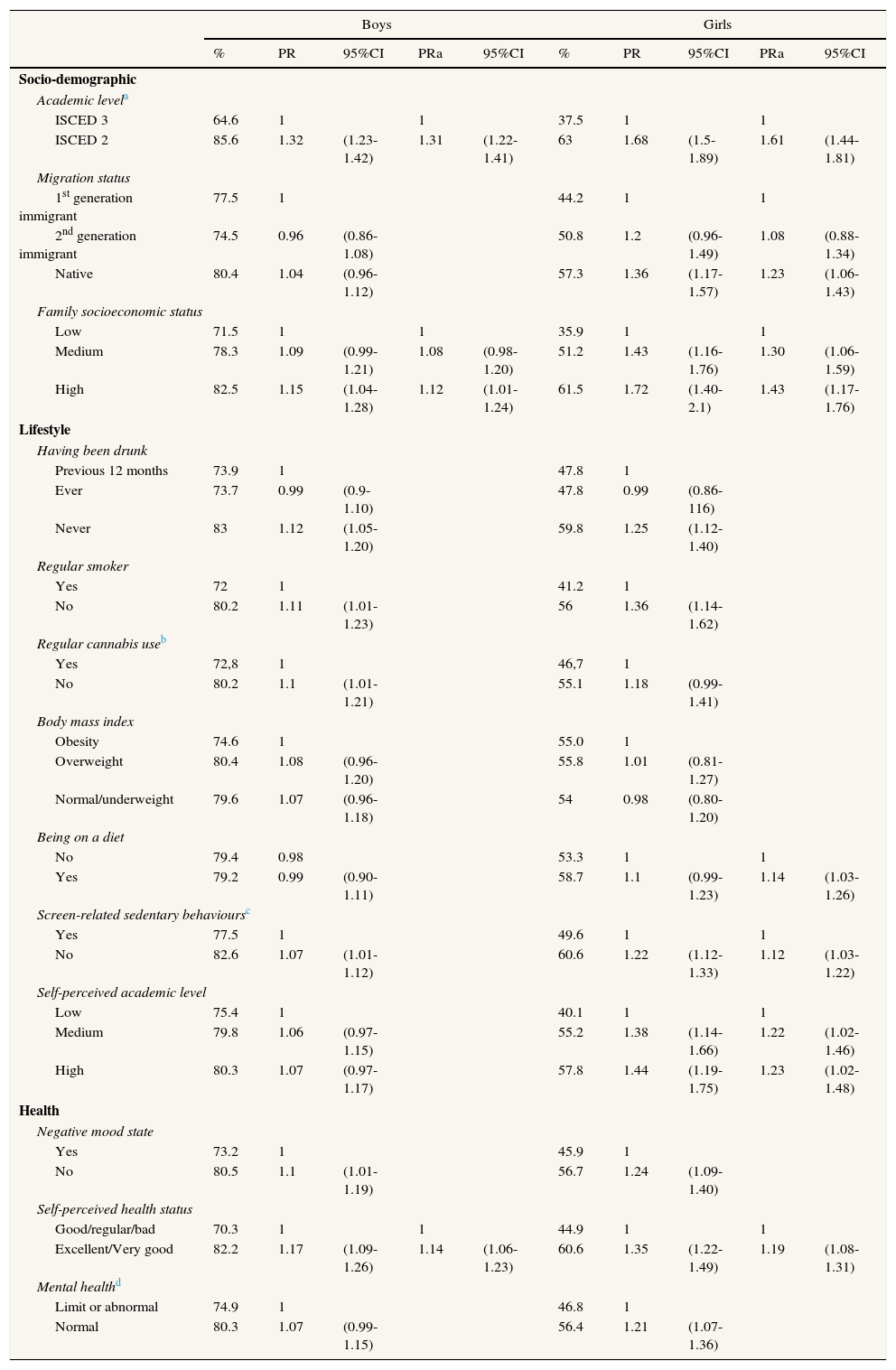

Table 2 shows the crude and adjusted PR for each sex. In both sexes, the prevalence of MVPA3 was higher among more junior students (ISCED 2), those from families with higher SES, and those who reported excellent or very good self-perceived health status. For example, the PR of MVPA3 in ISCED 2 compared to ISCED 3 students was 1.31 (95%CI: 1.22-1.41) and 1.61 (95%CI: 1.44-1.81) among boys and girls, respectively. Among girls but not boys, MVPA3 was also associated with being native (PR=1.23; 95% CI: 1.06-1.43; compared to 1st generation immigrants), being on a diet (PR=1.14; 95%CI: 1.03-1.26), not reporting screen-related sedentary behaviours, and having a good self-perceived academic level relative to classmates. Neither tobacco nor cannabis use were significantly associated with MVPA after adjustment for the other independent variables. Finally, our sensitivity analysis did not reveal remarkable differences between the results for the final models using MPVA5 and MPVA7 (results not shown).

Prevalence, prevalence ratios (PR) and adjusted PR (PRa) of moderate or vigorous physical activity of 60minutes or more at least 3 days a week (MVPA3) for each independent variable and each sex.

| Boys | Girls | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | PR | 95%CI | PRa | 95%CI | % | PR | 95%CI | PRa | 95%CI | |

| Socio-demographic | ||||||||||

| Academic levela | ||||||||||

| ISCED 3 | 64.6 | 1 | 1 | 37.5 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| ISCED 2 | 85.6 | 1.32 | (1.23-1.42) | 1.31 | (1.22-1.41) | 63 | 1.68 | (1.5-1.89) | 1.61 | (1.44-1.81) |

| Migration status | ||||||||||

| 1st generation immigrant | 77.5 | 1 | 44.2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2nd generation immigrant | 74.5 | 0.96 | (0.86-1.08) | 50.8 | 1.2 | (0.96-1.49) | 1.08 | (0.88-1.34) | ||

| Native | 80.4 | 1.04 | (0.96-1.12) | 57.3 | 1.36 | (1.17-1.57) | 1.23 | (1.06-1.43) | ||

| Family socioeconomic status | ||||||||||

| Low | 71.5 | 1 | 1 | 35.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Medium | 78.3 | 1.09 | (0.99-1.21) | 1.08 | (0.98-1.20) | 51.2 | 1.43 | (1.16-1.76) | 1.30 | (1.06-1.59) |

| High | 82.5 | 1.15 | (1.04-1.28) | 1.12 | (1.01-1.24) | 61.5 | 1.72 | (1.40-2.1) | 1.43 | (1.17-1.76) |

| Lifestyle | ||||||||||

| Having been drunk | ||||||||||

| Previous 12 months | 73.9 | 1 | 47.8 | 1 | ||||||

| Ever | 73.7 | 0.99 | (0.9-1.10) | 47.8 | 0.99 | (0.86-116) | ||||

| Never | 83 | 1.12 | (1.05-1.20) | 59.8 | 1.25 | (1.12-1.40) | ||||

| Regular smoker | ||||||||||

| Yes | 72 | 1 | 41.2 | 1 | ||||||

| No | 80.2 | 1.11 | (1.01-1.23) | 56 | 1.36 | (1.14-1.62) | ||||

| Regular cannabis useb | ||||||||||

| Yes | 72,8 | 1 | 46,7 | 1 | ||||||

| No | 80.2 | 1.1 | (1.01-1.21) | 55.1 | 1.18 | (0.99-1.41) | ||||

| Body mass index | ||||||||||

| Obesity | 74.6 | 1 | 55.0 | 1 | ||||||

| Overweight | 80.4 | 1.08 | (0.96-1.20) | 55.8 | 1.01 | (0.81-1.27) | ||||

| Normal/underweight | 79.6 | 1.07 | (0.96-1.18) | 54 | 0.98 | (0.80-1.20) | ||||

| Being on a diet | ||||||||||

| No | 79.4 | 0.98 | 53.3 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Yes | 79.2 | 0.99 | (0.90-1.11) | 58.7 | 1.1 | (0.99-1.23) | 1.14 | (1.03-1.26) | ||

| Screen-related sedentary behavioursc | ||||||||||

| Yes | 77.5 | 1 | 49.6 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| No | 82.6 | 1.07 | (1.01-1.12) | 60.6 | 1.22 | (1.12-1.33) | 1.12 | (1.03-1.22) | ||

| Self-perceived academic level | ||||||||||

| Low | 75.4 | 1 | 40.1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Medium | 79.8 | 1.06 | (0.97-1.15) | 55.2 | 1.38 | (1.14-1.66) | 1.22 | (1.02-1.46) | ||

| High | 80.3 | 1.07 | (0.97-1.17) | 57.8 | 1.44 | (1.19-1.75) | 1.23 | (1.02-1.48) | ||

| Health | ||||||||||

| Negative mood state | ||||||||||

| Yes | 73.2 | 1 | 45.9 | 1 | ||||||

| No | 80.5 | 1.1 | (1.01-1.19) | 56.7 | 1.24 | (1.09-1.40) | ||||

| Self-perceived health status | ||||||||||

| Good/regular/bad | 70.3 | 1 | 1 | 44.9 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Excellent/Very good | 82.2 | 1.17 | (1.09-1.26) | 1.14 | (1.06-1.23) | 60.6 | 1.35 | (1.22-1.49) | 1.19 | (1.08-1.31) |

| Mental healthd | ||||||||||

| Limit or abnormal | 74.9 | 1 | 46.8 | 1 | ||||||

| Normal | 80.3 | 1.07 | (0.99-1.15) | 56.4 | 1.21 | (1.07-1.36) | ||||

PR: prevalence ratio; PRa: PR adjusted; 95%CI: confidence interval of 95%.

Our results show that only 12% of students in Barcelona in 2012 met the WHO recommendations for MVPA. MVPA was considerably lower among girls and also among ISCED 3 students, suggesting a decrease in MVPA related to aging. We found that MPVA was positively associated with SES and self-perceived health status.

Less than one-eighth of students achieved the WHO-recommended levels MVPA (12%), which is consistent with some national and international studies,7,10,24 although other authors have reported MVPA rates of 50-70%.24–26 Such disparities may be due to a number of reasons. First, some studies use less stringent MVPA recommendations than this study (WHO recommendations). Second, research using accelerometers to determine MVPA levels appear to overestimate MVPA because they record incidental lower intensity exercise. Finally, some studies include low intensity forms of physical activity, such as walking.24,26

In line with previous research,25 we observed gender differences in MVPA levels, with boys reporting higher rates, both at ISCED 2 and ISCED 3. These differences may be because boys’ perceive fewer barriers to practising physical activity, and have more options for participation in sport, at both the school and leisure time.27 In addition, boys and girls practise activities of different intensity, the latter generally practising lower intensity activities.9,14

The most notable result is the decrease in MVPA between ISCED 2 and ISCED 3 in both sexes, although the decrease was more pronounced in girls. In our context, the strongest contributor to this decrease is probably the removal of compulsory physical activity from the school curriculum (physical education is compulsory in ISCED 2 but not in ISCED 3).14 Other authors have suggested that the transition from ISCED 2 to ISCED 3 involves more study time and screen use, such that ISCED 3 students have less time for physical activity.10,14 Decreased MVPA may also be due to girls’ biological maturation, which occurs around the time of transition to ISCED 3, and has been found to be related to lower participation in physical activities28. Some studies have shown that the differences between sexes disappear after a adjustment for biological age.28,29

Individual SES was also related to MVPA in both sexes, in that individuals with higher SES were more likely to meet MVPA recommendations. A recent review shows similar results, with higher SES associated with greater physical activity in 58% of studies.11 These differences could be because more disadvantaged families have generally lower paid jobs and poorer labour conditions, and teenagers from these households have to spend more of their free time doing housework or part time work, diminishing their availability to practise physical activity. Moreover, parents with poorer labour conditions may lead their children to be less active through their influence as role models.30 Additionally, those from lower SES backgrounds are likely to live in neighbourhoods and communities where parks and recreational facilities are less common or of a lower quality than those in more affluent neighbourhoods.6 Poorer awareness of the benefits of physical activity among families with lower SES could also explain these observed differences.11 In addition, we found an association between MVPA and immigration status among girls. First and second generation immigrant girls may belong to families with a distinct gender concept, where girls could have a more traditional role and may practise less physical activity.31 Nonetheless, more research is needed to explore the effect of country of origin on physical activity.

In terms of health-related variables, we found a positive relationship between self-perceived health status and MVPA levels in both sexes. This is consistent with previous studies indicating that physically active teenagers are more likely to have a positive perception of their health status than less active teenagers.32,33 This finding suggests that MVPA has a positive effect on teenagers’ health.1 Unlike other studies, we did not observe an association between MVPA and cannabis or tobacco use,13,34 perhaps because some studies indicate that the relationship is only seen in those adolescents who practice high intensity activities.34

Regarding the limitations of the present study, most data in this study are self-reported, except for the anthropometric measurements and the school-related variables. Although the objective measures are generally considered more robust, anonymous questionnaires on physical activity have been shown to have good validity and reliability, and remain a valuable tool for estimating levels of physical activity.35 Another limitation of this study could be the definition of physical activity used (practising MVPA for ≥1hour/day on ≥3 days/week) because there is no consensus on how to study physical activity using self-reported variables.36 Furthermore, our sensitivity analysis did not highlight remarkable differences between the results obtained using different MVPA variables. Finally, this study used a cross-sectional design, which allows us only to observe associations between variables, but not to infer causality in the observed relations.

In conclusion, this is the first study to analyse the WHO-recommended levels of MVPA and associated variables using a large representative sample of teenage students (13-18 years) from Barcelona city. The low levels of MVPA observed in this study, as defined by the WHO, suggest that an effort is needed to promote and/or to remove potential barriers to physical activity among adolescents, and this should be a public health priority. This study suggests that efforts to increase MVPA need to address gender and SES disparities, which appear to have a strong influence on MVPA. Additionally, policy makers should consider making physical activity part of the compulsory curriculum for ISCED 3 students.

The school setting is one of the most obvious places to target improvement in physical activity, since it provides the facilities, curriculum (including extra-curricular activities), policies and setting for students to participate in MVPA, independent of their SES.30 For this reason re-orienting education and health policy to incorporate physical activity and associated resources in the school setting, particularly for ISCED 3 students, should be considered. Finally, it would be interesting to conduct a study to know the reasons for the socioeconomic inequalities in physical activity in the adolescents of Barcelona, taking special attention to what happens during the changes between educational programs and with extracurricular activities.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that children and teenagers aged 5-17 years participate in at least 60minutes of moderate or vigorous physical activity daily. Despite the importance of physical activity for health and wellbeing, a low percentage of teenagers in developed countries meet the WHO recommendations for moderate or vigorous physical activity.

What does this study add to the literature?Only 12% of teenagers of Barcelona (Spain) meet the WHO vigorous or moderate physical activity recommendations. Girls and teenagers with lower socioeconomic status have generally the lowest levels of moderate or vigorous physical activity. Increases in moderate or vigorous physical activity are needed to address gender and Socioeconomic disparities. Policy makers should consider making physical activity a part of the compulsory curriculum for ISCED 3 students (17-18 years old).

Erica Briones-Vozmediano.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsA. Espelt, A. Pérez and A. Ruiz-Trasserra were involved in the conception and design of the work. A. Ruiz-Trasserra and A. Espelt carried out the analysis of the data. A. Espelt, A. Pérez, A. Ruiz-Trassera, X. Continente and K. O’Brien interpreted the results. The first version of the manuscript was written by A. Ruiz-Trasserra and was subsequently improved by all authors, with important intellectual contributions. All authors have approved the final version and are jointly responsible for adequate revision and discussion of all aspects included in the manuscript.

FundingThe study was partially funded by the Plan Nacional Sobre Drogas (PI2011/107), Spanish Government.

Conflicts of interestsNone.

The authors wish to thank the teachers, students and schools that participated in the study. We also thank the staff from the Community Health Service and the Evaluation and Intervention Methods Service at Barcelona Public Health Agency, who collaborated on this project. This research article represents partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Masters of Public Health for Alícia Ruiz Traserra, University of Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona.