We examined the association between immigration status and depression in a nationally representative sample of adults in Spain. In addition, we assessed whether this association differed by sex/gender and social support.

MethodWe used de-identified data from the European Health Interview Survey conducted in Spain in 2014 (n=21,226) and 2020 (n=20,136). Our study outcomes were self-reported diagnosis of depression and antidepressant use. We fitted Poisson regression models to quantify the association between immigration status and each outcome, before and after adjusting for age, sex/gender, marital status, educational level, employment status, smoking status, healthcare use, social support, and self-rated health. We obtained prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). We also tested interaction terms to evaluate whether the associations of interest differed by survey year and further by sex/gender and with social support.

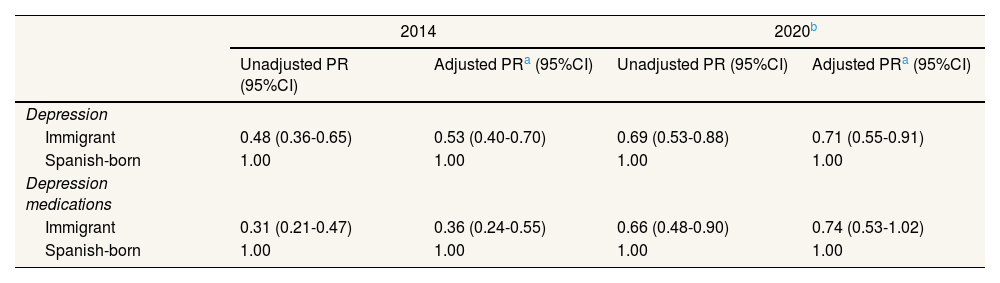

ResultsIn 2014 and 2020, we observed a lower prevalence of depression among immigrant adults than among native Spanish adults (adjusted PR2014=0.53, 95%CI: 0.40- 0.70; PR2020=0.71, 95%CI: 0.55-0.91). However, for antidepressant use, this association was significant only in 2014 (adjusted PR2014=0.36, 95%CI: 0.24-0.55). Although the association of immigration status with antidepressant use differed with survey year, these associations did not change with sex/gender or social support.

ConclusionsOur findings call attention to depression and mental health-related outcomes in Spain, regardless of immigration status, sex/gender or social support.

Examinamos la asociación entre el estado migratorio y la depresión en una muestra representativa de ámbito nacional de adultos en España. Además, evaluamos si esta asociación difiere según el sexo/género y el apoyo social.

MétodoUtilizamos datos anonimizados de la Encuesta Europea de Salud realizada en España en 2014 (n=21.226) y en 2020 (n=20.136). Los resultados de nuestro estudio fueron el diagnóstico autoinformado de depresión y el uso de antidepresivos. Usamos modelos de regresión de Poisson para cuantificar la asociación entre el estado migratorio y cada resultado, antes y después de ajustar por edad, sexo/género, estado civil, nivel educativo, situación laboral, tabaquismo, uso de atención médica, apoyo social y salud autopercibida. Obtuvimos razones de prevalencia (RP) e intervalos de confianza del 95% (IC95%). También examinamos términos de interacción para evaluar si las asociaciones de interés diferían según el año de la encuesta, y además según el sexo/género y el apoyo social.

ResultadosEn 2014 y 2020 observamos una menor prevalencia de depresión en los inmigrantes que en los adultos nacidos en España (RP2014 ajustada=0,53, IC95%: 0,40-0,70; RP2020=0,71, IC95%: 0,55-0,91). Sin embargo, para el uso de antidepresivos esta asociación solo fue significativa en 2014 (RP2014 ajustada=0,36, IC95%: 0,24-0,55). Aunque la asociación del estado migratorio con el uso de antidepresivos difiere según el año de la encuesta, estas asociaciones no cambiaron con el sexo/género o el apoyo social.

ConclusionesNuestros hallazgos llaman la atención sobre la depresión y las consecuencias relacionadas con la salud mental en España, independientemente del estado migratorio, el sexo/género y el apoyo social.

In Europe, previous studies have reported that immigrants generally exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than native populations.1–4 In Spain, a country with the third highest proportion of immigrant population in the European Union,5 evidence for this association is mixed,6–9 with studies reporting a higher prevalence,9 lower prevalence,6,7 or no difference in the prevalence of depression between immigrants and native Spanish adults.8 In addition, immigrants are less likely to consume antidepressants.6,8 Thus, it is important to examine the associations of immigration status with depression and related outcomes.

Social, economic, and psychosocial factors influenced the association between immigration status and depression.1,10,11 Factors contributing to these social inequalities include unemployment, lower social support, and previous mental health conditions. Precarious working conditions, for example, have been shown to significantly increase the risk of depression among immigrant workers.12,13 Additionally, immigrants often face unique challenges such as discrimination, which is linked to depressive symptoms.14 Gender inequalities have also been documented among immigrants, with depression being more common among women than men.8 Similarly, social support tends to buffer the stress related to immigration status,15 and thus, may change the relationships of immigration status with depression and antidepressant use.

Spain presents unique challenges regarding the migration processes, as noted in previous studies.16,17 Currently, 17.1% of the population has an immigrant background, mostly from South America or Africa.5 However, our understanding of social inequalities in mental health, based on immigration status, remains limited. Therefore, we aimed to examine whether there is an association of immigration status with depression and antidepressant use in adults who participated in the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) of Spain in 2014 and 2020, and whether this association differs by sex/gender and social support.

MethodStudy design and data collectionWe conducted a cross-sectional analysis of immigrant and native Spanish adults aged 18 or older who participated in the EHIS conducted in Spain in 2014 and 2020. These surveys used a stratified multistage sampling approach to ensure the representation of Spain's noninstitutionalized population. Data collection for the 2014 survey took place between February 2014 and January 2015, while the 2020 survey was conducted between July 2019 and July 2020. The response rates for the two surveys were 71% and 59%, respectively.

Study variablesConsistent with a previous study in Spain,18 we assessed depression using self-reported information about two survey questions: “Have you ever been depressed?” and “Has a medical doctor told you that you had depression”. We deemed a positive response to both questions as indicative of depression. Additionally, we considered the use of antidepressants prescribed in the last two weeks if individuals reported depression. We measured immigration status by country of birth: born in Spain or outside Spain, including adults born in countries with a human development index (HDI) <0.80.19 The cutoff point is recommended for comparison purposes, as countries with HDI ≥0.80 have social conditions similar to Spain, and thus, immigrants from these countries may have similar outcomes to the Spanish population. In addition, we used country of birth to determine the continent of origin of the immigrant population as follows: Asia, Latin America, Europe, and Africa.

Consistent with previous studies,6,12,20–23 we considered age (continuous and categorical), sex/gender (men or women), marital status (married or not), educational level (no formal education or primary, secondary, or tertiary), employment status, occupation or social class, use of primary healthcare (last visit to a general practitioner in the past four weeks, between four weeks and 12 months, and 12 months or more/never), social support, smoking status, and self-rated health.

Employment status was specified using information on contractual conditions and the actual employment situation as follows: permanent as someone who had a permanent contract and was currently working; precarious as someone who was currently working part-time fixed-term contracts, or with informal employment arrangements, including unspecified situations and unpaid family workers; business as someone who was working as a business or professional employee or worker independent; others included individuals who were working because they retired or pre-retired, students, or a person with disabilities; and unemployed included individuals who were not working but had a previous occupation. Occupation or social class (hereafter, social class) was collected using the following categories: directors of establishments with ten or more employees, self-employed or intermediate occupations, supervisors/technical occupations, primary sector/semi-qualified occupations, and non-qualified occupations. For analytical purposes, we specified social class as non-manual (including the first three categories) or manual (including the last two categories).

We used questions from the social support scale Oslo 322 regarding the number of people one can count on, the extent to which people care about what happened to people, or people can get help from neighbors. The sum of the responses to these questions ranged from 3 to 14 points. We categorized social support as low (3–8), moderate (9-11), or strong (12–14). Responses to the question “Do you currently smoke?” (yes, every day; yes, but not daily; no, currently but I have smoked; and I have never smoked) to specify smoking status as current (participants responded that they currently smoke daily or not), former (those who have smoked but not currently), or never (those who have never smoked). Self-rated health was collected via the question “In the last 12 months would you say that your health has been very good, good, regular, bad, or very bad?”. We used categorized self-rated health as very good/good (very good/good) and fair/poor (regular, bad, or very bad).24–26 All variables were self-reported.

Study populationOf the total sample (n=22,842 for 2014 and n=22,072 for 2020), we excluded records of individuals who were <18 years of age at the time of the interview (n=521 and 503), records without information on marital status (n=22 and 64), social support (n=39 and 26), employment status (n=61 and 29), smoking (n=13 and 19), occupation or social class (n=523 and 934), and records of individuals from countries with an HDI ≥ 0.80 (n=437 and 361). These exclusions yielded final analytical samples of 21,226 and 20,136 in 2014 and 2020, respectively.

Statistical analysisWe calculated descriptive statistics for selected characteristics according to immigration status using mean (± standard deviation), frequencies, and percentages, depending on whether the variable was continuous or categorical. We also calculated the prevalence of depression for each characteristic in the total population and by immigration status. We used t-test for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables to determine significant differences or associations, respectively. We fitted a Poisson regression to obtain prevalence ratios (PR) and their 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) and quantify the association of immigration status with depression and antidepressant use before and after adjusting for age, sex/gender, marital status, educational level, employment status, smoking status, healthcare use, social support, and self-rated health. To determine whether the association varied with the survey year, an interaction term between immigration status and survey year was tested in the adjusted model. Additionally, we examined a three-way interaction to determine whether the association between immigration status and depression varied with sex/gender and with social support in each survey.

All data management and analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 accounting for the sampling design used in the surveys. Table 1 presents the unweighted sample sizes. However, all estimates presented in the tables were weighted, that is, proportions, standard errors (SE), PR, and 95%CI.

Descriptive statistics of the study population by immigration status. European Health Interview Surveys in Spain, 2014 and 2020.

| 2014 | 2020 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable, % (SE) | Immigrant,n=1,37810.2 (0.32) | Native,n=19,84889.8 (0.32) | Total,n=21,226 | Immigrant,n=1,50612.3 (0.34) | Native,n=18,63087.7 (0.34) | Total,n=20,136 |

| Continent of origin | ||||||

| Asia | 4.6 (0.68) | 6.4 (0.89) | ||||

| Latin America | 48.8 (1.70) | 48.6 (1.52) | ||||

| Europe | 21.3 (1.38) | 21.4 (1.25) | ||||

| Africa | 25.2 (1.57) | 23.7 (1.29) | ||||

| Age (years), mean (SE) | 38.4 (0.44) | 50.1 (0.16) | 48.9 (0.15) | 41.0 (0.39) | 51.4 (0.17) | 50.0 (0.16) |

| 18-24 | 41.6 (1.72) | 22.2 (0.41) | 24.2 (0.41) | 32.6 (1.48) | 20.4 (0.42) | 22.0 (0.42) |

| 25-34 | 30.2 (1.49) | 19.8 (0.33) | 20.9 (0.33) | 30.7 (1.37) | 17.5 (0.34) | 19.1 (0.34) |

| 35-44 | 18.7 (1.33) | 18.9 (0.34) | 18.8 (0.33) | 21.7 (1.23) | 19.4 (0.36) | 19.6 (0.35) |

| 45-64 | 6.5 (0.79) | 15.2 (0.29) | 14.3 (0.28) | 10.2 (0.88) | 17.3 (0.33) | 16.4 (0.31) |

| >65 | 2.9 (0.59) | 23.9 (0.33) | 21.8 (0.31) | 4.7 (0.60) | 25.4 (0.36) | 22.8 (0.33) |

| Sex/gender | ||||||

| Men | 44.6 (1.70) | 49.6 (0.43) | 49.1 (0.42) | 44.5 (1.52) | 49.9 (0.46) | 49.2 (0.44) |

| Marital statusa | ||||||

| Married | 61.3 (1.68) | 60.4 (0.42) | 60.5 (0.42) | 59.2 (1.50) | 60.1 (0.45) | 60.0 (0.44) |

| Educational level | ||||||

| No formal/primary | 48.5 (1.71) | 52.6 (0.43) | 52.2 (0.42) | 43.1 (1.51) | 47.5 (0.46) | 46.9 (0.44) |

| Secondary | 37.5 (1.64) | 27.6 (0.39) | 28.6 (0.39) | 42.6 (1.50) | 30.9 (0.43) | 32.3 (0.42) |

| Tertiary | 14.0 (1.04) | 19.8 (0.35) | 19.2 (0.33) | 14.3 (1.03) | 21.6 (0.38) | 20.8 (0.36) |

| Social class | ||||||

| No manual | 18.6 (1.23) | 40.2 (0.42) | 38.0 (0.41) | 18.6 (1.21) | 41.3 (0.45) | 38.5 (0.43) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Permanent | 23.5 (1.36) | 27.8 (0.38) | 27.4 (0.37) | 31.2 (1.41) | 33.1 (0.43) | 32.9 (0.42) |

| Precarious | 31.6 (1.61) | 16.5 (0.35) | 18.0 (0.36) | 35.6 (1.47) | 16.4 (0.37) | 18.7 (0.38) |

| Business | 5.4 (0.70) | 8.5 (0.70) | 8.1 (0.23) | 5.2 (0.64) | 8.1 (0.25) | 7.8 (0.24) |

| Other | 11.6 (1.18) | 35.8 (0.40) | 33.4 (0.38) | 10.5 (0.92) | 35.6 (0.42) | 32.5 (0.39) |

| Unemployed | 27.9 (1.54) | 11.4 (0.28) | 13.1 (0.30) | 17.6 (1.14) | 6.8 (0.24) | 8.1 (0.25) |

| Healthcare usea | ||||||

| Within 4 weeks | 26.9 (1.57) | 29.9 (0.38) | 29.6 (0.38) | 20.2 (1.18) | 21.6 (0.37) | 21.4 (0.35) |

| 4 weeks – 1 year | 48.2 (1.70) | 48.2 (0.43) | 48.2 (0.42) | 59.8 (1.50) | 61.4 (0.45) | 61.2 (0.43) |

| >1 year/never | 24.9 (1.46) | 21.9 (0.37) | 22.2 (0.36) | 20.0 (1.27) | 17.0 (0.36) | 17.4 (0.35) |

| Social support | ||||||

| Low | 13.2 (1.07) | 4.9 (0.18) | 5.7 (0.19) | 11.4 (0.92) | 3.4 (0.15) | 4.4 (0.17) |

| Moderate | 53.6 (1.70) | 33.3 (0.40) | 35.4 (0.41) | 45.9 (1.51) | 29.4 (0.42) | 31.4 (0.41) |

| Strong | 39.2 (1.62) | 61.8 (0.42) | 58.9 (0.42) | 42.7 (1.51) | 67.2 (0.43) | 64.2 (0.42) |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Current | 23.1 (1.42) | 26.2 (0.38) | 26.0 (0.37) | 18.9 (1.22) | 23.4 (0.40) | 22.8 (0.38) |

| Former | 17.7 (1.26) | 27.7 (0.38) | 26.7 (0.36) | 13.3 (1.00) | 24.6 (0.38) | 23.2 (0.36) |

| Never | 59.2 (1.66) | 46.0 (0.43) | 47.3 (0.42) | 67.8 (1.42) | 52.0 (0.46) | 53.9 (0.44) |

| Self-rated health | ||||||

| Fair/poor | 26.7 (1.53) | 30.3 (0.38) | 29.9 (0.38) | 22.5 (1.23) | 25.4 (0.38) | 25.0 (0.36) |

| Depression, yes | 4.6 (0.68) | 9.6 (0.24) | 9.1 (0.22) | 5.2 (0.63) | 7.6 (0.23) | 7.3 (0.21) |

| Depression medications, yesa | 2.0 (0.39) | 6.2 (0.19) | 5.8 (0.18) | 3.2 (0.49) | 4.9 (0.18) | 4.7 (0.17) |

SE: standard error.

Table 1 displays key characteristics of the study population stratified by immigration status in EHIS 2014 and 2020. Most of the immigrant population originated from Latin American countries. Compared with the Spanish population, regardless of the survey year, immigrants were younger, less likely to be men, less educated, less likely to work in a non-manual job, more likely to have precarious employment or be unemployed, and more likely to rate their health as very good/good. Both self-reported prevalence of depression and antidepressant use were higher in the Spanish population than in the immigrant population.

The overall prevalence estimates for self-reported depression were 9.1% and 7.3% in 2014 and 2020, respectively (data not shown). In both 2014 and 2020, regardless of immigration status, the prevalence of depression was lower among men, those who were married, those with better employment status, and those who rated their health as very good/good (Table 2). Between 2014 and 2020, the prevalence of antidepressant use increased in the immigrant population (62.5% vs. 80.3%), whereas the opposite was true for native Spanish adults (74.4% in 2014 vs. 72.3% in 2020).

Prevalence estimates of depression for selected characteristics of adults aged 18 years or older by immigration status. European Health Interview Surveys in Spain, 2014 and 2020.

| 2014 | 2020 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immigrant | Native | Immigrant | Native | |

| Characteristics | Yes, % (SE) | Yes, % (SE) | Yes, % (SE) | Yes, % (SE) |

| Overall | 4.6 (0.68) | 9.6 (0.24) | 5.2 (0.63) | 7.6 (0.23) |

| Continent of origin | ||||

| Asia | - | 0.8 (0.85) | ||

| Latin America | 5.9 (1.12) | 6.2 (0.92) | ||

| Europe | 4.7 (1.38) | 8.1 (1.86) | ||

| Africa | 2.7 (1.08) | 1.7 (0.78) | ||

| Age, years | ||||

| 18-34 | 4.2 (1.21)a | 2.9 (0.35) | 2.7 (0.89) | 3.0 (0.42) |

| 25-34 | 4.1 (1.01) | 6.0 (0.46) | 4.4 (1.02) | 4.5 (0.45) |

| 35-44 | 6.5 (1.64) | 10.0 (0.58) | 5.3 (1.18) | 7.1 (0.51) |

| 45-64 | 4.5 (1.95) | 13.8 (0.71) | 10.4 (2.71) | 9.4 (0.57) |

| 65+ | 3.3 (2.11) | 15.8 (0.54) | 15.9 (5.45) | 12.7 (0.51) |

| Sex/gender | ||||

| Men | 1.4 (0.53) | 5.7 (0.28) | 2.6 (0.69) | 5.1 (0.26) |

| Women | 7.1 (1.14) | 13.2 (0.38) | 7.3 (0.99) | 10.1 (0.36) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 2.8 (0.64) | 9.2 (0.31)a | 4.4 (0.76)a | 7.0 (0.28) |

| Non-married | 7.5 (1.42) | 10.1 (0.36) | 6.3 (1.10) | 8.6 (0.37) |

| Education | ||||

| No formal/primary | 4.3 (0.88)a | 13.5 (0.38) | 3.7 (0.84)a | 10.8 (0.38) |

| Secondary | 5.8 (1.36) | 6.1 (0.37) | 6.0 (1.03) | 5.9 (0.39) |

| Tertiary | 2.3 (0.88) | 4.1 (0.36) | 7.2 (1.93) | 3.0 (0.29) |

| Social class | ||||

| No manual | 3,1 (1.01)a | 6.4 (0.30) | 5.0 (1.31)a | 5.7 (0.31) |

| Manual | 4.9 (0.80) | 11.8 (0.34) | 5.2 (0.72) | 8.9 (0.32) |

| Employment status | ||||

| Permanent | 3.2 (0.97) | 4.4 (0.32) | 2.7 (0.77) | 4.0 (0.30) |

| Precarious | 4.1 (1.16) | 6.3 (0.53) | 4.9 (1.06) | 4.8 (0.50) |

| Business | - | 4.7 (0.61) | 3.5 (1.94) | 2.3 (0.43) |

| Other | 6.9 (2.13) | 16.2 (0.48) | 12.9 (3.19) | 13.1 (0.46) |

| Unemployed | 6.2 (1.65) | 9.9 (0.76) | 6.1 (1.52) | 9.8 (0.99) |

| Healthcare use | ||||

| Within 4 weeks | 8.5 (1.91) | 16.7 (0.55) | 13.7 (2.07) | 15.0 (0.65) |

| 4 weeks – 1 year | 3.9 (0.81) | 8.3 (0.32) | 3.8 (0.75) | 6.4 (0.26) |

| >1 year/never | 1.6 (0.78) | 2.8 (0.30) | 0.8 (0.59) | 2.6 (0.34) |

| Social support | ||||

| Low | 6.7 (1.77)a | 19.3 (1.50) | 9.6 (2.32) | 15.5 (1.53) |

| Moderate | 4.7 (1.05) | 10.5 (0.43) | 6.2 (1.03) | 9.2 (0.46) |

| Strong | 3.6 (0.91) | 8.3 (0.28) | 2.9 (0.76) | 6.5 (0.26) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Current | 4.9 (1.27)a | 8.9 (0.48) | 7.2 (1.76)a | 8.1 (0.50)a |

| Former | 4.2 (1.44) | 8.8 (0.44) | 5.7 (1.77) | 6.9 (0.43) |

| Never | 4.5 (0.94) | 10.5 (0.35) | 4.5 (0.72) | 7.7 (0.31) |

| Self-rated health | ||||

| Very good/good | 1.8 (0.46) | 3.4 (0.17) | 2.1 (0.49) | 2.9 (0.16) |

| Fair/poor | 12.3 (2.14) | 23.9 (0.62) | 15.9 (2.17) | 21.5 (0.69) |

| Depression medications | ||||

| Yes | 62.5 (9.73) | 74.4 (1.42) | 80.3 (5.67) | 72.3 (1.73) |

| No | 3.5 (0.61) | 5.3 (0.19) | 2.7 (0.47) | 4.3 (0.18) |

SE: standard error.

Table 3 shows the results of the association between immigration status and depression stratified by survey year. In the unadjusted analyses, the prevalence of depression was 52% (PR: 0.48, 95%CI: 0.36-0.65) and 31% (PR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.53-0.88) lower among the immigrant population than among native Spanish adults in 2014 and 2020, respectively. In the adjusted analyses, these associations remained the same in 2014 and 2020. However, their strengths were attenuated for both 2014 (PR: 0.53, 95%CI: 0.50-0.79) and 2020 (PR: 0.71, 95%CI: 0.55-0.91).

Unadjusted and adjusted prevalence ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the association of immigration status and continent of origin with depression by survey year: European Health Interview Surveys in Spain, 2014 and 2020.

| 2014 | 2020b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted PR (95%CI) | Adjusted PRa (95%CI) | Unadjusted PR (95%CI) | Adjusted PRa (95%CI) | |

| Depression | ||||

| Immigrant | 0.48 (0.36-0.65) | 0.53 (0.40-0.70) | 0.69 (0.53-0.88) | 0.71 (0.55-0.91) |

| Spanish-born | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Depression medications | ||||

| Immigrant | 0.31 (0.21-0.47) | 0.36 (0.24-0.55) | 0.66 (0.48-0.90) | 0.74 (0.53-1.02) |

| Spanish-born | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: prevalence ratio.

We observed a similar pattern when assessing antidepressant consumption. For both survey years, immigrants reported a 69% lower use of these medications in 2014 and a 34% in 2020 lower use of this medications, as compared with their native Spanish counterparts. In the adjusted analyses, this association remained statistically significant only in 2014 (PR: 0.36, 95%CI: 0.24-0.55). We found a significant effect measure modification by immigration status and survey year for antidepressant medication use (p interaction: 0.01) but not for depression (p interaction: 0.07). However, we did not find statistically significant interactions for depression or for the use of antidepressants for immigration status with survey year and sex/gender (p interactions: 0.32 depression and 0.12 antidepressant use), or social support (p interactions: 0.28 depression and 0.31 antidepressant use).

DiscussionOur findings show a lower probability of self-reported prevalence of depression and antidepressant use among immigrants than among native Spanish adults in both EHIS 2014 and 2020. However, the association between immigration status and antidepressants was only significant in 2014 before and after adjustment. Finally, although the association of immigration status with antidepressant use differed with survey year, our findings remained the same regardless of sex/gender or social support.

Our finding of a lower prevalence of depressive symptoms and antidepressant use in the immigrant population in 2014 can be explained, at least partially, by the economic crisis that lasted from 2008 to 2014. This crisis led to the return of immigrant populations to their countries of origin between 2010 and 2015, due to economic difficulties and dramatic job losses.27 Thus, it is possible that immigrants who remained had more favorable conditions in terms of social position and health status. We continue to observe immigrant health advantage in 2020 despite immigrants having more precarious employment after the economic crisis,28,29 being employed in positions considered precarious13 or essential jobs,30 and having worse living conditions than their native Spanish counterparts. Moreover, other potential explanations could be the healthy immigrant effect, where there is a selection effect for healthy adults to migrate to another country, and the low use of the healthcare system observed among immigrants, especially for mental health.23,31,32 The latter is associated with stigma and cultural beliefs among immigrants, leading to avoiding seeking care, and thus, depression may be underestimated for this population.33,34 Despite the low prevalence of depression among immigrant adults, it is worth noting that the prevalence of depression in 2020 was higher among those aged 45 years or older than among their native Spanish peers. This was not the case in 2014, when a higher prevalence of depression among immigrants was observed among those aged 18-34 years. This change could be due because younger immigrants adults in 2014 encountered harsher socioeconomic conditions than their native Spanish counterparts,35,36 whereas older immigrants adults could have experience worst physical and mental health due to cumulative life and working conditions as well as the lock down during COVID-19 than their younger counterparts in 2020.37,38

We did not find a difference in depression or antidepressant use by sex/gender or social support, regardless of migrant status or survey year. Our findings regarding the lack of heterogeneity related to sex/gender are inconsistent with previous research suggesting that immigrant women have worse mental health than Spanish native women. However, this is not the case for immigrant men.8,9 There are several possible explanations for the observed differences. First, men are more likely to minimize depressive symptoms and respond differently to questions regarding their mental health conditions. Second, women are more likely to use the healthcare system,39 and thus, are more likely to be aware of their mental health. Finally, women suffer from poor employment conditions and are responsible for dependent care,8 and their work conditions have worsened over time.40 However, despite their access to healthcare and employment conditions, women, and especially immigrant women, coped better than men with the impact of the economic crisis,41 which could have protected their mental health. Regarding our findings related to social support, evidence suggests that social support plays a significant role in mitigating the negative association between immigration status and depression in Spain.15 However, this relationship may depend on the level of social integration and economic stability experienced by different immigrant groups, such as homeownership rates.42 Further research is needed to understand the specific mechanisms through which sex/gender and social support influence mental health outcomes among immigrants.

An important limitation of this study is the sample size of the immigrant population, which only allows us to analyze immigrants as a single group without accounting for key differences by country of origin or cultural background. Furthermore, we excluded immigrants from countries with HDI >0.80 as they could have similar health status as native Spanish adults. However, we repeated the analyses including immigrants from countries with HDI >0.80, and the results did not change significantly from the results presented in Table 3. The latter finding suggests that such exclusion was unlikely to bias our findings. Second, immigrants experiencing language barriers or precarious conditions (e.g., homelessness) were not represented in these surveys. Third, we did not account for length of stay in Spain for the immigrant population because of small size for some cells and the high correlation of the variable with immigration status. Future studies should consider length of stay, which may provide insights into the health status of the immigrant population. Fourth, we did not consider depression severity. Finally, part of the fieldwork of the 2020 survey was conducted during the state of alarm in Spain due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The latter may have precluded a greater outreach, leading to low participation in the immigrant population. Similarly, COVID-19 may have biased our results, especially for immigrants who bear a greater burden of infection and death due to their essential jobs.43,44 Despite these limitations, the strength of this study is that we provided a nationwide assessment of the evolution of depression prevalence among the immigrant population in Spain using the two most recent waves of the European Health Interview Survey. Moreover, we observed individuals across a wide age range.

Our findings suggest that there is a protective effect for depression among the immigrant population in Spain regardless of sex/gender or social support. Future research should investigate factors contributing to depression and mental health-related outcomes in the immigrant population. The findings of such investigations could provide insights to tailor programs and interventions to address the mental health status of the population, particularly depression, regardless of immigration status, sex/gender, or social support.

Immigrants generally exhibit a higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than native populations. In Spain, evidence for this association is mixed, with some studies reporting a higher prevalence, lower prevalence, or no difference in the prevalence of depression between immigrants and Spanish natives.

What does this study add to the literature?Our findings suggest that there is a protective effect for depression among the immigrant population in Spain, regardless of sex/gender and social support.

What are the implications of the results?The findings call for the need to tailor programs and interventions to address depression and mental health-related outcomes of the population regardless of immigration status, sex/gender or social support.

We used data from the National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estadistica), Madrid, Spain, available at: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176784&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195298&idp=1254735573175#tabs-1254736195298

Editor in chargeAlberto Lana.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsL.N. Borrell conceptualized the study design, conducted the analyses, prepared the first draft of the manuscript and critically reviewed the final manuscript. N. Lanborena, E. Rodríguez-Álvarez contributed to the study conceptualization and critically reviewed the manuscript and the results. J. Díez and S. Yago-González critically reviewed the manuscript and the results. L.N. Borrell, J. Díez, S. Yago-González, N. Lanborena and E. Rodríguez-Álvarez have read and approved the final manuscript.

FundingThis work was supported by the Multiannual Agreement reference # CM/BG/2023-002 (L.N. Borrell).

Conflicts of interestNone.