Special Issue on Health Economics

More infoTo review several behavioral economics-based interventions (“healthy nudges”) aimed at mitigating the overuse and underuse of healthcare resources —phenomena associated with poorer health outcomes and increased costs.

MethodA comparative case study approach is used to assess the effectiveness of ten studies designed to improve treatment adherence and prevent underuse, as well as those focused on improving prescribing practices to address overuse.

ResultsFirst, healthy nudges are generally effective, although there is considerable variability in their outcomes. Effectiveness compared to the control group ranges from 5% to over 30%. Second, similar strategies may yield divergent results depending on the context (e.g., medication adherence vs. vaccination uptake). Third, the effect of healthy nudges appears to diminish after the intervention ends, especially for economic incentives. However, default options seem to remain persistent over time.

ConclusionsThe article examines the pros and cons of healthy nudges in the use and provision of healthcare services. The evidence gathered from the selected studies suggests that nudges may help rationalize healthcare use. However, challenges remain, such as ensuring the long-term persistence of effects and evaluating their impact on well-being and cost-effectiveness.

Revisar varias intervenciones basadas en la economía del comportamiento (empujones saludables) destinadas a mitigar tanto la sobreutilización como la infrautilización de los recursos sanitarios, fenómenos ambos asociados con peores resultados en salud y mayores costes.

MétodoSe aplica un enfoque de estudio de caso comparativo para evaluar la efectividad de diez estudios diseñados para mejorar la adherencia al tratamiento y prevenir la infrautilización, así como aquellos enfocados en mejorar las prácticas de prescripción para abordar el sobretratamiento.

ResultadosEn primer lugar, los empujones saludables son generalmente efectivos, aunque existe una considerable variabilidad en sus resultados. Su efectividad en comparación con un grupo control varía entre el 5% y más del 30%. En segundo lugar, estrategias similares pueden generar resultados divergentes dependiendo del contexto (p. ej., adherencia a la medicación frente a cobertura de vacunación). En tercer lugar, el efecto de los empujones saludables parece disminuir una vez que la intervención ha terminado, en especial para los incentivos económicos. Sin embargo, las opciones por defecto parecen mantenerse persistentes a lo largo del tiempo.

ConclusionesEl artículo examina los pros y los contras de los empujones saludables en el uso y la provisión de servicios sanitarios. La evidencia recopilada de los estudios seleccionados sugiere que los empujones pueden ayudar a racionalizar el uso de los servicios sanitarios. No obstante, persisten desafíos, como garantizar el mantenimiento a largo plazo de los efectos y evaluar su impacto en el bienestar y su relación coste-efectividad.

This article employs a comparative case study approach1 to analyze how various behavior-based strategies, referred to here as “healthy nudges”, address the issues of overuse and underuse of healthcare across different contexts. Misuse of healthcare is associated with poorer health outcomes and increased costs.2 We focus particularly on how practitioners (suppliers) and patients (demanders) can be nudged to prescribe (in the case of healthcare professionals) and adhere (in the case of patients) health interventions, including public health programmes, such as vaccination campaigns or healthy lifestyle recommendations.

Healthy nudges to boost adequacyBehavioral economics3 analyzes individual behavior from a more realistic psychological perspective than the standard economic model of human behavior. This branch of economics explains a wide variety of systematic errors committed by agents, referred to as biases. Naturally, stakeholders in the healthcare system are not immune to cognitive biases. For example, consider the initial responses of governments, health authorities, and citizens to the COVID-19 pandemic, which provide clear examples of psychological factors that may have biased the public health measures taken at the time.4 In this way, many stakeholders believed that COVID-19 was probably “not as bad” (optimism bias) and were overly confident in this mistaken belief (overconfidence bias). Such cognitive biases are common across many other dimensions of the healthcare environment, which is why the application of behavioral economics tools has continued to grow in health economics studies since the 2000s.

Nudges5 are the most popular behaviour-based interventions. Although, according to Thaler and Sunstein5 nudges are subtle interventions that steer individuals toward desirable choices without restricting their options or significantly altering economic incentives, in this article we use the term “healthy nudges” in a broader sense, encompassing both what nudges strictly are —psychological tools that reshape the decision environment— and material incentives. This laxity in defining healthy nudges makes sense, among other reasons, because economic incentives are often used to reinforce the impact of nudges.

A comparative case study approach to assess healthy nudgesThe comparative case study approach is a qualitative research method used to analyze multiple cases in depth, emphasizing the contextual factors that influence outcomes. Unlike single-case studies, which focus on an individual case in isolation, comparative case study compares different cases to identify patterns, similarities, and differences. In contrast to systematic reviews, which are primarily quantitative and use structured protocols for aggregating evidence from multiple studies, the comparative case study approach is fundamentally qualitative. The cases are selected by researchers based on their theoretical and practical relevance, with the aim of ensuring diversity or representativeness. As is evident, case selection in a comparative case study is inherently subjective, but not arbitrary, as it seeks to understand how and why specific phenomena (such as healthy nudges) work within different contexts.

Hence, in this manuscript, we present the main features of ten papers. These studies have been selected to exemplify, to some extent, the achievements and limitations of a broad range of healthy nudges in three fields: adherence, prescription, and healthy habits.

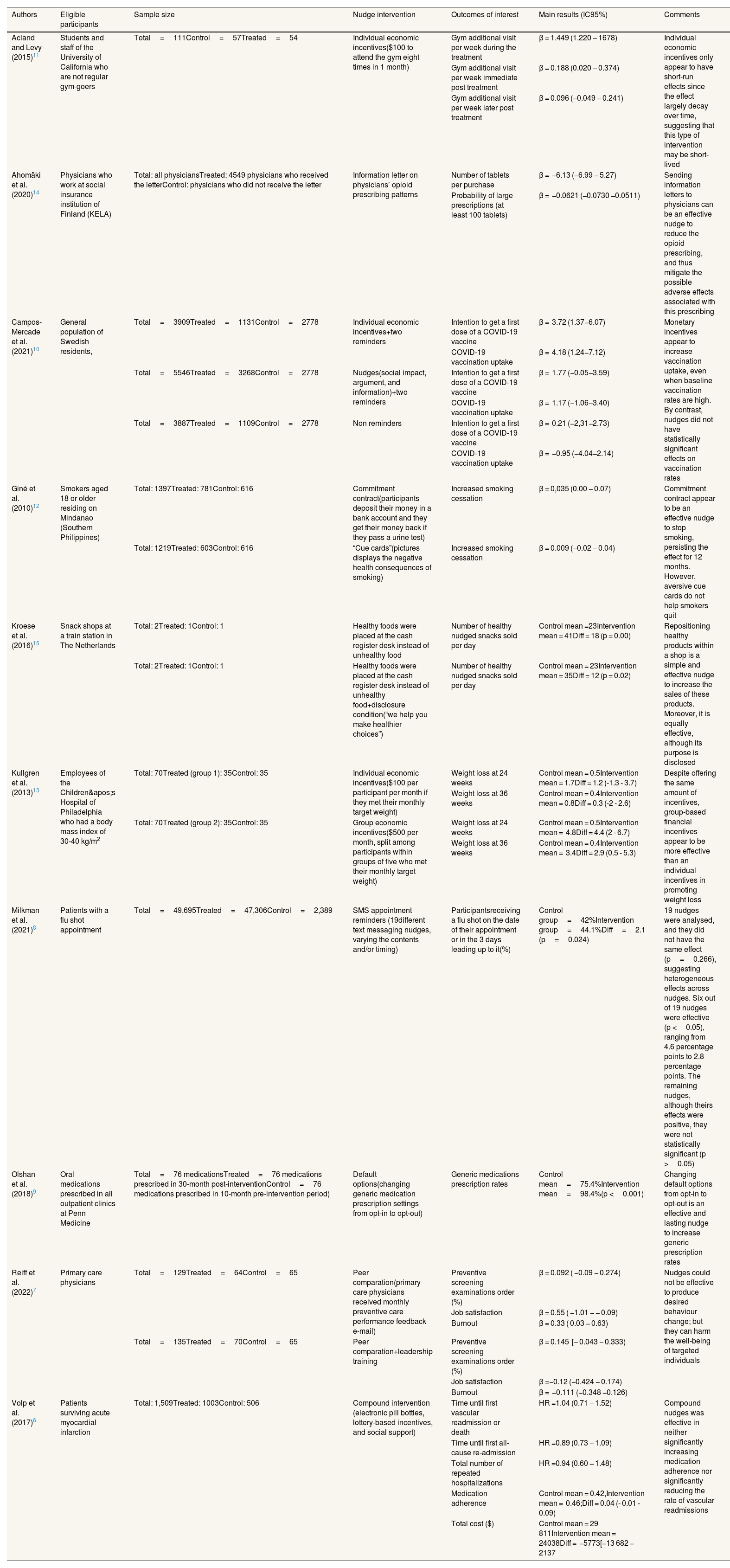

A critical assessment of the effectiveness of healthy nudge casesTable 1 presents the ten selected studies. For each study, information about participants’ eligibility, sample size, type of intervention, outcomes, and main results is provided. Additional comments, explaining the key findings or covering other aspects, are also included.

Analyzed studies on healthy nudges in different contexts.

| Authors | Eligible participants | Sample size | Nudge intervention | Outcomes of interest | Main results (IC95%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acland and Levy (2015)11 | Students and staff of the University of California who are not regular gym-goers | Total=111Control=57Treated=54 | Individual economic incentives($100 to attend the gym eight times in 1 month) | Gym additional visit per week during the treatment | β = 1.449 (1.220 − 1678) | Individual economic incentives only appear to have short-run effects since the effect largely decay over time, suggesting that this type of intervention may be short-lived |

| Gym additional visit per week immediate post treatment | β = 0.188 (0.020 − 0.374) | |||||

| Gym additional visit per week later post treatment | β = 0.096 (−0.049 − 0.241) | |||||

| Ahomäki et al. (2020)14 | Physicians who work at social insurance institution of Finland (KELA) | Total: all physiciansTreated: 4549 physicians who received the letterControl: physicians who did not receive the letter | Information letter on physicians’ opioid prescribing patterns | Number of tablets per purchase | β = −6.13 (−6.99 − 5.27) | Sending information letters to physicians can be an effective nudge to reduce the opioid prescribing, and thus mitigate the possible adverse effects associated with this prescribing |

| Probability of large prescriptions (at least 100 tablets) | β = −0.0621 (−0.0730 −0.0511) | |||||

| Campos-Mercade et al. (2021)10 | General population of Swedish residents, | Total=3909Treated=1131Control=2778 | Individual economic incentives+two reminders | Intention to get a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine | β = 3.72 (1.37−6.07) | Monetary incentives appear to increase vaccination uptake, even when baseline vaccination rates are high. By contrast, nudges did not have statistically significant effects on vaccination rates |

| COVID-19 vaccination uptake | β = 4.18 (1.24−7.12) | |||||

| Total=5546Treated=3268Control=2778 | Nudges(social impact, argument, and information)+two reminders | Intention to get a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine | β = 1.77 (−0.05−3.59) | |||

| COVID-19 vaccination uptake | β = 1.17 (−1.06−3.40) | |||||

| Total=3887Treated=1109Control=2778 | Non reminders | Intention to get a first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine | β = 0.21 (−2,31−2.73) | |||

| COVID-19 vaccination uptake | β = −0.95 (−4.04−2.14) | |||||

| Giné et al. (2010)12 | Smokers aged 18 or older residing on Mindanao (Southern Philippines) | Total: 1397Treated: 781Control: 616 | Commitment contract(participants deposit their money in a bank account and they get their money back if they pass a urine test) | Increased smoking cessation | β = 0,035 (0.00 − 0.07) | Commitment contract appear to be an effective nudge to stop smoking, persisting the effect for 12 months. However, aversive cue cards do not help smokers quit |

| Total: 1219Treated: 603Control: 616 | “Cue cards”(pictures displays the negative health consequences of smoking) | Increased smoking cessation | β = 0.009 (−0.02 − 0.04) | |||

| Kroese et al. (2016)15 | Snack shops at a train station in The Netherlands | Total: 2Treated: 1Control: 1 | Healthy foods were placed at the cash register desk instead of unhealthy food | Number of healthy nudged snacks sold per day | Control mean =23Intervention mean = 41Diff = 18 (p = 0.00) | Repositioning healthy products within a shop is a simple and effective nudge to increase the sales of these products. Moreover, it is equally effective, although its purpose is disclosed |

| Total: 2Treated: 1Control: 1 | Healthy foods were placed at the cash register desk instead of unhealthy food+disclosure condition(“we help you make healthier choices”) | Number of healthy nudged snacks sold per day | Control mean = 23Intervention mean = 35Diff = 12 (p = 0.02) | |||

| Kullgren et al. (2013)13 | Employees of the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia who had a body mass index of 30-40 kg/m2 | Total: 70Treated (group 1): 35Control: 35 | Individual economic incentives($100 per participant per month if they met their monthly target weight) | Weight loss at 24 weeks | Control mean = 0.5Intervention mean = 1.7Diff = 1.2 (-1.3 - 3.7) | Despite offering the same amount of incentives, group-based financial incentives appear to be more effective than an individual incentives in promoting weight loss |

| Weight loss at 36 weeks | Control mean = 0.4Intervention mean = 0.8Diff = 0.3 (-2 - 2.6) | |||||

| Total: 70Treated (group 2): 35Control: 35 | Group economic incentives($500 per month, split among participants within groups of five who met their monthly target weight) | Weight loss at 24 weeks | Control mean = 0.5Intervention mean = 4.8Diff = 4.4 (2 - 6.7) | |||

| Weight loss at 36 weeks | Control mean = 0.4Intervention mean = 3.4Diff = 2.9 (0.5 - 5.3) | |||||

| Milkman et al. (2021)8 | Patients with a flu shot appointment | Total=49,695Treated=47,306Control=2,389 | SMS appointment reminders (19different text messaging nudges, varying the contents and/or timing) | Participantsreceiving a flu shot on the date of their appointment or in the 3 days leading up to it(%) | Control group=42%Intervention group=44.1%Diff=2.1 (p=0.024) | 19 nudges were analysed, and they did not have the same effect (p=0.266), suggesting heterogeneous effects across nudges. Six out of 19 nudges were effective (p <0.05), ranging from 4.6 percentage points to 2.8 percentage points. The remaining nudges, although theirs effects were positive, they were not statistically significant (p >0.05) |

| Olshan et al. (2018)9 | Oral medications prescribed in all outpatient clinics at Penn Medicine | Total=76 medicationsTreated=76 medications prescribed in 30-month post-interventionControl=76 medications prescribed in 10-month pre-intervention period) | Default options(changing generic medication prescription settings from opt-in to opt-out) | Generic medications prescription rates | Control mean=75.4%Intervention mean=98.4%(p <0.001) | Changing default options from opt-in to opt-out is an effective and lasting nudge to increase generic prescription rates |

| Reiff et al. (2022)7 | Primary care physicians | Total=129Treated=64Control=65 | Peer comparation(primary care physicians received monthly preventive care performance feedback e-mail) | Preventive screening examinations order (%) | β = 0.092 ( −0.09 − 0.274) | Nudges could not be effective to produce desired behaviour change; but they can harm the well-being of targeted individuals |

| Job satisfaction | β = 0.55 ( −1.01 − − 0.09) | |||||

| Burnout | β = 0.33 ( 0.03 − 0.63) | |||||

| Total=135Treated=70Control=65 | Peer comparation+leadership training | Preventive screening examinations order (%) | β = 0.145 [− 0.043 − 0.333) | |||

| Job satisfaction | β =−0.12 (−0.424 − 0.174) | |||||

| Burnout | β = −0.111 (−0.348 −0.126) | |||||

| Volp et al. (2017)6 | Patients surviving acute myocardial infarction | Total: 1,509Treated: 1003Control: 506 | Compound intervention (electronic pill bottles, lottery-based incentives, and social support) | Time until first vascular readmission or death | HR =1.04 (0.71 − 1.52) | Compound nudges was effective in neither significantly increasing medication adherence nor significantly reducing the rate of vascular readmissions |

| Time until first all-cause re-admission | HR =0.89 (0.73 − 1.09) | |||||

| Total number of repeated hospitalizations | HR =0.94 (0.60 − 1.48) | |||||

| Medication adherence | Control mean = 0.42,Intervention mean = 0.46;Diff = 0.04 (- 0.01 - 0.09) | |||||

| Total cost ($) | Control mean = 29 811Intervention mean = 24038Diff = −5773[−13 682 − 2137 |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; HR: hazard ratio.

A few key patterns can be extracted from the inspection of Table 1. Firstly, most interventions are successful (i.e., they demonstrate a statistically significant effectiveness increment over the control), with the exception of the studies by Volp et al.6 and Reiff et al.7 Nevertheless, a considerable variability arises across studies (i.e., effectiveness over the control group ranges from 5%, when text messages are used to remind vaccination appointments,8 to more than 30% when default options are used to augment generic prescriptions9), and even within the same study and for the same type of intervention (e.g., there were significant differences amongst 19 different text messaging nudges to boost flu vaccination8).

Secondly, a similar approach (e.g., a hybrid strategy combining incentives and nudges) may lead to a different result (e.g., individual incentives plus reminders succeeded in increasing vaccination uptake,10 but incentives didn’t work when they were included in a compound intervention to increase medication adherence of acute myocardial infarction survivors6), highlighting the influence of the context.

Lastly, although most of the studies focus on the effectiveness of the healthy nudges during the treatment, there is some mixed evidence on post treatment effects. Acland and Levy11 found that their intervention remains effective during both the treatment (5 weeks) and immediate posttreatment (8 weeks) periods, but not in a longer term (21 weeks later). Giné et al.12, in turn, found that the effect of a commitment contract for smoking cessation had an impact even 6 months after the intervention finished. Nevertheless, it is worth noting that, though the commitment contract used was effective, only 11% of the targeted smokers enrolled in the programme to quit smoking, so probably it suffered from a selection bias. Similarly, Olshan et al.9 verified that overall increases in generic prescription rates were sustained for 2.5 years after implementation of an opt-out generic prescribing system. However, Kullgren et al.13 find that the effect of group incentives diminishes twelve weeks after incentives ended.

DiscussionThe first and foremost message from the comparative case study reported in this manuscript is that healthy nudges are, generally, effective. That is, they affect behaviour in the intended direction. This does not mean, however, that the effect found in the remaining studies, even when sizeable, is generally large. A considerable variability arises indeed across studies, in such a way that whereas some of the healthy nudges are highly effective,9,10,14,15 others get more modest results.8,12 Hence, a considerable variability across studies arises from our comparative analysis. These findings are congruent with those reported by DellaVigna and Linos,16 who show that nudges, after controlling for publication biases, increase effectiveness an 8%.

Furthermore, some of the studies, while effective during the treatment period (usually a few weeks) or, moreover, during the immediate posttreatment period (a few more weeks), do not maintain their effectiveness in the long-term posttreatment phase.11 Alternatively, although the effectiveness of some interventions remains significant, it tends to decline over time.13 This finding aligns with studies that have analysed the persistence of nudges effects on habit formation over time.17 This issue appears to be particularly severe for interventions aimed at changing lifestyles, suggesting that further research is needed on mechanisms that can help establish long-lasting healthy habits.

Besides these general conclusions, the in-depth analysis of the selected studies reveals some relevant implications for future investigations in this field. First, obviously, that some studies only produce slight -though statistically significant- improvements does not mean that they cannot be cost-effective measures. Therefore, it would be desirable to evaluate this issue when a new healthy nudge is implemented. It is logical to expect that sending SMS appointment reminders and boosting vaccination rates by an average of 5% over the baseline is clearly cost-effective.8 However, this point is not always so straightforward. As Table 1 shows, no statistically significant effect on medication adherence or medical costs was found by Volp et al.,6 so their intervention was not cost-effective. This highlights the importance of measuring not only the differential effect with respect to the control group, but also the incremental cost.

Likewise, something frequently overlooked in the literature is that the impact size of healthy nudges is not only highly sensitive to the specific type of nudge used, but it is also contingent on the duration for which the intervention is applied. Thus, interventions should be designed in such a way that allows for tracking the effect of the intervention after its conclusion. This could help to elucidate whether, as often observed in pay-for-performance schemes in healthcare systems, and some of the studies11,13 included in our selection points up, economic incentives effectiveness decay as they are withdrawn.

In addition, the impact of healthy nudges on wellbeing has been hardly studied. Reiff et al.7 finds no significant effect from conveying peer comparison information to primary care physicians; however, it did significantly decrease job satisfaction and increase burnout. Thus, while a nudge might be successful (which does not occur in the study of Reiff et al.7), it could also harm subjective wellbeing. Therefore, nudges should not be evaluated solely on their ability to change behavior, but also on whether they could potentially harm wellbeing. These kinds of effects on welfare has been reported in other contexts, like energy.18 The fact that healthy nudges, even when effective, can harm the well-being of some individuals being nudged deviates from the primum non nocere principle to which they must adhere. Furthermore, this may contradict the concept of asymmetric paternalism of Camerer et al.,19 according to which nudges should benefit people who make systematic errors without harming rational individuals.

From our point of view, the necessity of exploring whether healthy nudges might be overestimating wellbeing gains opens new avenues for research into a practice that could be called “precision nudging”, consisting of launching nudges aimed specifically at those subjects most prone to react positively to being nudged, instead of one-size-fits-all approach. Artificial intelligence can be a valuable tool to design these “precision nudges” since artificial intelligence can process large volumes of personal data and generate a high-quality, personalized, real-time nudges. This kind of nudge has been already shown to be effective in the context of medication adherence.20 However, ethical issue of nudging people has existed since the concept's emergence in 2008 and it has been widely discussed in the previous literature.21 With the rise of artificial intelligence, a new concern has arisen regarding privacy. As previously mentioned, “precision nudging” requires a large volume of personal data and has been criticized for violating privacy and its potential for misuse.22,23

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsAll authors of this article have contributed significantly to each phase of the research and to the writing of the text. Each one has actively participated in the conception and design of the study, the collection and analysis of the bibliography, as well as in the preparation of the manuscript.

AcknowledgementsThis article has benefited from the accumulated experience in the two editions of the course ‘Improvement of Lifestyles and Reduction of Risk Factors, Behavioral Economics in the Service of Public Health,’ taught by one of the authors and organized by the Menorca School of Public Health. Our thanks to this institution, as well as to all the students who have attended the course.

FundingThis study was supported by Grant PID2023-148357NB-I00 from MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ‘ERDF/EU.

Conflicts of interestNone.