To know the characteristics of the studies that have paid attention to women who have sex with women (WSW) and to identify possible gaps in the interest of comprehensive sexual health in WSW.

MethodA scoping review on sexual health on WSW was conducted from 2000 to 2019. Papers with lack of focus on sexual health on WSW were excluded and a web tool was used to guarantee blindness. Information was extracted on the key characteristics of the studies and the quality of the evidence. The sexual health categories were comprehensive sexual health, specification of sexual practices in WSW, and recommendations provided.

Results39 studies were included, mostly cross-sectional. The gaps identified were the lack of evidence on sexual health, confusion about sexual orientation and sexual practices, lack of specific interest in comprehensive sexual health and the life cycle approach. Recommendations focused on WSW self-care; interventions aimed at clinical practice, research, education and prevention; and contributions of a feminist approach on sexual health of WSW.

ConclusionsThere are several gaps about in the knowledge about sexual health among WSW. Self-care improvement and specific strategies addressed to the unique characteristics of these women and their different and specific situation and health determinants are highlighted.

Conocer las características de los estudios centrados en mujeres que tienen sexo con mujeres (MSM) e identificar posibles lagunas en el interés sobre la salud sexual integral de las MSM.

MétodoRevisión sistemática exploratoria sobre salud sexual en MSM entre los años 2000 y 2019. Se excluyeron los estudios no centrados en salud sexual de MSM y se utilizó una herramienta web para asegurar el enmascaramiento. Se extrajo información sobre las características de los estudios y la calidad de la evidencia. Las categorías de análisis fueron: salud sexual integral, especificidad de prácticas sexuales en MSM y recomendaciones aportadas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 39 estudios, la mayoría transversales. Las lagunas identificadas fueron la falta de evidencia en salud sexual, la confusión entre orientación sexual y prácticas sexuales, la falta de interés específico en salud sexual integral y el enfoque de ciclo vital. Las recomendaciones se centraron en autocuidados de las MSM; intervenciones enfocadas a la práctica clínica, investigación, educación y prevención; y contribuciones desde un enfoque feminista sobre la salud sexual de las MSM.

ConclusionesExisten varias lagunas de conocimiento en la salud sexual de las MSM. Se destaca la necesidad de intervenir en la mejora del autocuidado y también de incluir estrategias específicas dirigidas a las características de estas mujeres, de acuerdo con sus realidades.

Several studies have identified some diseases, such as sexually transmitted infections (STI), to be more prevalent among women who have sex with women (WSW), including heterosexual women.1 Little is known regarding the sexual health of WSW.2 Indeed, several researches have highlighted the lack of studies investigating STIs in WSW suggesting that there are other factors apart from the biological determinants that should be considered, such as the difficulties in accessing to diagnosis and treatment in WSW.3

Studies that have been carried out in specific countries such as Brazil4 or Poland5 also have emphasized other barriers such as the lower visibility of health situations concerning WSW and the lack of opportunities to carry out this research in specific areas. For example, the risk of infection the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is still unknown in WSW, particularly in those more socioeconomically disadvantaged,6 as this disease has been globally studied more in men who have sex with men (MSM) than in WSW.7 The spread of some of these diseases is the result of lifestyles and stigmatization due to sexual orientation8. Furthermore, there are studies that suggest WSW receive less medical attention than the rest of the population.9

Other studies have showed that health providers assume that lesbian identity prevents sexual activity with men or that transmission of STIs among women is unlikely.10 Little literature exists on safe sex messages aimed at promoting healthy sexuality among lesbian women, which in turn leads to an absence of studies that analyze sexual behaviors within this group.11 This is the reason why precise risk associated with certain sexual practices cannot be defined and therefore, be able to design prevention campaigns.

International Organizations such as the United Nations as well as different studies, have highlighted the need to investigate about WSW and sexual and reproductive health,12 and have claimed the right of WSW to be treated equally and with non-discrimination.13

In this context of disparities in the sexual health of WSW that can potentially worsen their health and well-being, it is worth to investigate what studies have focused on STIs and sexual health of WSW and what are their characteristics. The research question intends to be answered by knowing the characteristics of the studies that have paid attention to WSW and by identifying possible gaps in the interest of comprehensive sexual health in WSW. Since MSM is a topic that has been further investigated compared to WSW, the present investigation aimed to focus on WSW.

MethodA scoping review is carried out, following the recommendations for this type of studies14 and adapting to the recommendations of PRISMA15 guide.

Search strategyThe search included the empirical literature published from 2000 to 2019 in five electronic databases: PubMed, Scielo, LILACS, Embase and CINAHL. These databases were chosen with the help of an informant from the Health Science library to provide the most comprehensive coverage of relevant studies conducted in this area.

The present scoping review followed the systematic review methodology proposed in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement.

The search terms were combined into two categories: the population of interest (WSW, lesbians, bisexual women, WSW or WSW/M) and the topic of interest (sexual health). The search terms for WSW and WSW/M included various phrases used to describe this population in health science research (for example lesbian, bisexual women, WSW or WSW/M). Search terms for health issues included STD, STD risks factors, sexual health, sexual habits, prevention, barriers and risk behaviours.

The search terms within each category were combined using the Boolean operator “or”. Then, the search results in all two categories were combined using the boolean operator “and”. Search syntax included: ((”lesbian“OR”bisexual women“OR”WSW“OR”WSW/M“) AND (”STD“OR”STD risk factors“OR”sexual health“OR”sexual habits“OR”prevention“OR”barriers“OR”risk behaviours”)).

An ancestry and descent search of the retrieved studies was performed to identify additional articles.

Inclusion criteria were studies about sexual health of WSW published in peer reviewed journals in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese. The following types of publications were included: original articles, reviews, clinical trials, books, documents, consensus conference, editorials, comparative studies, electronic supplements, guidelines, meta-analysis, government documents, multicenter studies. We excluded articles with health professional's opinions on sexual minorities, prevalence estimations of sexual minority populations, studies with migrants or refugees, conference abstracts, case studies, and reports in the gray literature.

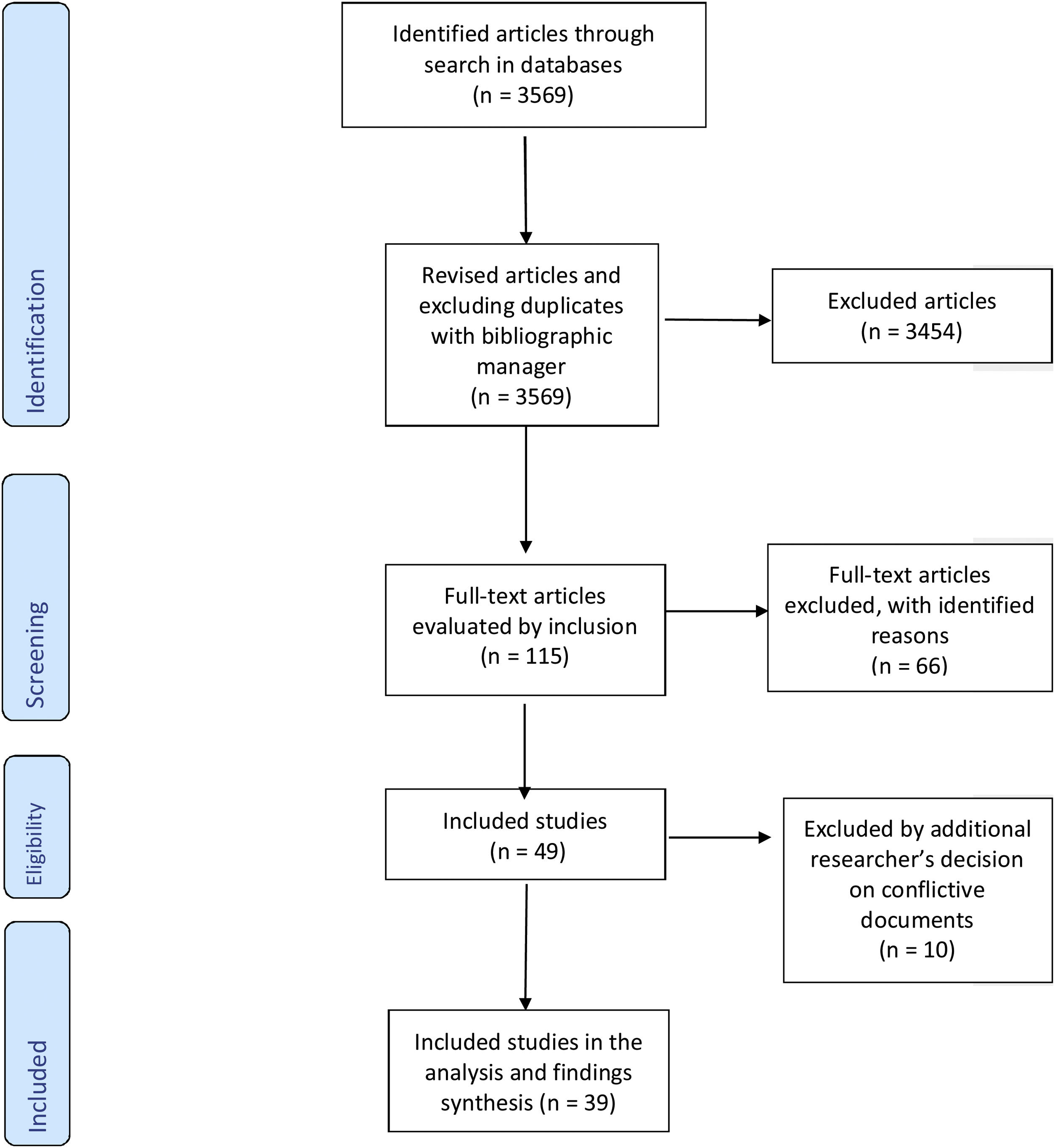

A total of 3569 articles were obtained. After this first phase, duplicates and those articles the title and/or abstract of which included the terms health (and non-sexual health), treatment or diagnosis were eliminated, as well as those in which the keywords used for the search did not appear. After applying these criteria, a total of 115 articles were obtained. All titles and abstracts were reviewed after completing the ancestry and descent search. Then, four researchers reviewed the full text of each article in pairs. The data was summarized if the article met the inclusion criteria, yielding a result of 49 selected works.

The review was carried out by the Rayyan QCRI16 web tool, which allowed for a blind review throughout the process. Any disagreement between these two authors was discussed with a third author until consensus was reached. Thus, 20 conflicting documents appeared, on which a third review was applied by an additional researcher, from which ten were excluded (Fig. 1).

The selection of the results of each article was examined by the researchers, so that each one read and reviewed the results and the positions found were discussed, thus allowing an analysis of the results in pairs.

Data analysisData extraction matrices were created to summarize the key characteristics of the studies, including country, study populations, and sample characteristics, year, study design, STIs studied and quality of evidence according to the type of study. The quality of the scientific evidence of the selected articles was classified according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)17 criteria.

Regarding comprehensive sexual health, the categories of extraction were created: areas of interest in sexual health, specification of sexual practices in WSW and recommendations of the studies from a comprehensive sexual health point of view.

Additionally, statements were identified that showed a feminist approach focused on sexual health in WSW within the studies, when applicable. Gender was considered as a health determinant that increases the knowledge of women's health, or that indicates changes in gender structures impacting on women's health equality18.

ResultsOut of 3569 publications identified, a total of 39 were finally selected. The methodology used was mainly cross-sectional (64.1%). Four cohort studies were applied and one of them was multicentric.3 Qualitative methodology included interviews (7.7%) and focus groups (10.25%). Two systematic reviews were also retrieved.2,19Table 1 shows the characteristics of the studies and the evidence level according to the SIGN classification. Populations sampled in the studies varied from 16 to 5714 people. Nine studies focused on comparing WSW and WSWM. In addition, seven studies were addressed specifically to African American WSW and two specifically identified only lesbians in their study population,20,21 23 studies (59%) were focused on specific STIs and 17 (43.6%) were interested in other aims or included STIs in general, as added information.

Descriptive characteristics of the selected studies.

| First author (year) | Country | Study design | Population | Age range (mean) | N | Reported frequency/rates of STI in WSW | Evidence (SIGN) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muzny (2014) | USA | Cross-sectional | AA WSW | 18-45 | 196 | C Bisexual 39 (66%); Lesbian 54 (45%) | 3 |

| Muzny (2013) | USA | Cross-sectional | AA WSW | 18-45 | 196 | BV Bisexual 35 (59%); Lesbian 51 (43%) | 3 |

| Arend (2003) | USA | Interviews | AA/latina HIV+ | 30-40 | 16 | Entire population study HIV+ | 4 |

| Tat (2015) | USA | Systematic Review | WSW | NA | 56 | HIV Prevalence in East Asia-Pacific: 0%; Latin America and the Caribbean: 0-2,9%; Sub-Saharan Africa: 7,7-9,6%. | 2 ++ |

| Zaidi (2016) | Kenya | Cross-sectional | WSW | 18-55 | 280 | Any STD 95 (33,9%). | 3 |

| Pinto (2005) | Brasil | Cross-sectional | WSW | 18-50 | 145 | TR 5 (3,5%); BV 48 (33,8%), F 31 (25,6%), CL 2 (1,5), HIV 4 (2,9%), HBV 10 (7%); HCV 3 (2,1%); HPV 9 (6,2%). | 3 |

| Wang (2012) | China | Cross-sectional | WSW | (25,6) | 224 | GR 35 (15,8%), CL 8 (3,5), SY 1 (0,5%), BV 32 (14,4%), HBV 2 (0,9%), HCV 1 (0,5%), CL 15 (6,9%) | 3 |

| Muzny (2016) | USA | Cross-sectional | AA WSW | 18-34 | 63 | CL 7 (33,3%) | 3 |

| Logie (2015) | Canada | Cross-sectional | WSW | 18-70 | 466 | HPV 30 (6,4%); CL 19 (4,1%); HV 16 (3,4); HIV 6 (1,4%) | 3 |

| Muzny (2014) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSW/WSWM | (22) | 63 | Cl 7 (33%); TR 1 (5%) | 3 |

| Muzny (2014) | USA | Cross-sectional | AA WSW/WSWM | (28) | 163 | TR 17 (22%); CL 17 (22%); GR 9 (11%); SY 1 (1%); HPV 4 (5%); HIV 1 (1%) | 3 |

| Massad (2014) | USA | Multicenter cohort study | WSW/WSWM, HIV+/ HIV- | (37) | 438 (73 WSW) | HPV in HIV+ 18 (42%) in HIV- 6 (27%) | 2 ++ |

| Schick (2012) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSW | 18-69 | 3116 | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Bailey (2004) | UK | Cross-sectional | Lesbian and bisexual W | 16-53 | 708 | BV Lesbian 214 (32,5%); Bisexual 8 (18,6%) | 3 |

| Marrazo (2000) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSW | (32) | 149 | HPV (19%); HSV-2 (30,3%); BV (8%-52%) | 3 |

| Molin (2016) | Norway | Cohort study | WSW/WSWM | 16-62 | 64 WSW | CL 25 (4%); MC 7 (1%); GR 2 (0,3%); HIV; SY 0 | 2 + |

| Fishman (2003) | USA | Cross-sectional | lesbian not bisexual | (46) | 78 | HIV- 67 (70%); 33% did not know serostatus | 3 |

| Mulllinax (2016) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSWM | 18-55 | 2755 | No STI screening 1766 (64,1%) | 3 |

| Reisner (2010) | USA | Cohort study | WSW/WSM | (32) | 310 (WSW:83) | An STD diagnosis 5% and 17%had a history of 1 or more STDs. | 2 + |

| Doull (2018) | USA | Online focus groups | Lesbian and bisexual girls | 14-18 | 160 | No data about STI in study available | 4 |

| Polek (2017) | USA | Cross-sectional | Bisexual, lesbian | (31) | 135/113 | Ever received HPV vaccine Lesbian 16 (16.8%), bisexual 30 (26,8%) | 3 |

| Logie (2015) | Canada | Cohort study | Lesbian, bisexual, queer | (29) | 44 | Current STI: 9 (20.45%) | 2 + |

| Muzny (2013) | USA | Focus groups | AA WSW | 19-43 | 29 | No data about STI in study available | 4 |

| Rowen (2013) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSW | <20->60 | 1557 | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Logie (2012) | US | Focus groups | HIV+ lesbian, bi, Q, T | 27-57 | 23 | Entire population study HIV+ | 4 |

| Marrazzo (2005) | USA | Focus groups | Lesbian, bisexual | 18-29 | 23 | BV 6 (26%) Other STD 3 (13%) | 4 |

| Fish (2005) | UK | Cross-sectional | Lesbians | 21-50 | 1066 | Pap smear 135 (15%) | 3 |

| Silberman (2016) | Argentina | Cross-sectional | homo and bisexual | (29) | 161 | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Forcey (2015) | USA | Systematic Review | WSW | ** | 14 | BV Prevalence in studies from 5,9 to 56,2% | 3 |

| Singh (2011) | USA | Cohort study | WSW/WSWM | 15-24 | 5714/3644 | CT = 7,1% | 2 ++ |

| Cox (2009) | Australia | Cross-sectional | WSW | 16-45 | 32 | No data about STI in study available | 4 |

| Eaton (2008) | USA | Cross-sectional | WSW | (35) | 275 | VPH 16 (5%) | 3 |

| Champion (2005) | USA | Interview | AA Bisexual W | 22-45 | 23 | No data about STI in study available | 4 |

| Bailey (2004) | UK | Cross-sectional | WSW | (31) | 708 | BV 222 (31.4%); C 130 (18,4%); TR 9 (1,3%); HV 8 (1,1%); CL 4 (0,6%); GR 2, PID 2 (0,3%) | 3 |

| Kowalczyk (2019) | Poland | Cross-sectional | WSW/WSWM | 28-34 | 146/113 | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Wang (2012) | China | Cross-sectional | WSW | (26) | 224 | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Rufino (2018) | Brasil | Interviews | WSW | 18-50 | 34 | No data about STI in study available | 4 |

| Fujji (2019) | Japan | Cross-sectional | WSW | 19-55 | 92 WSW | No data about STI in study available | 3 |

| Xu (2010) | USA | Cross-sectional | W (same sex) | 18-59 | 6500 | HSV-2 30.3% in WSW-past year, and 36.2% in WSW-ever | 3 |

AA WSW: African American women who have sex with women; BV: bacterial vaginosis; C: Candida; CL: Chlamydia trachomatis; F: fungi; GR: gonorrhea; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HPV: human papilloma virus; HSV-2: herpes simplex virus type 2; HV: herpes virus; Les: lesbian; MC: Mycobacterium; NA: not applicable; PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; Q: queer; STD: sexually transmitted disease; SY: syphilis; T: transgender; TR: Trichomonas; VH: vaginal herpes.

Regarding STIs specifically in WSW, eight studies were interested on Bacterial Vaginosis, with proportions varying from 14,4% to 43%. They were cross-sectional or qualitative studies, so that evidence less than 3 was not achieved. Forcey's19 systematical review found a previous prevalence between 5.9% and 56.2% and other found a proportion of 43% in lesbian women. Other authors focused their work on specific diseases such candidiasis, Chlamydia, human papilloma virus or herpes simplex virus, among others. Nine studies were focused on HIV, finding frequencies from 0% to 42% of HIV in WSW and two of these researches were addressed to HIV positive people.

Some studies provided claims related to a comprehensive sexual health vision of WSW.

A total of 25 general contributions were extracted from the different studies in which any of these statements were observed (64.1%), pointing at certain factors that could determine the sexual health of the WSW from a holistic point of view such as the type of partner,22 generally referring to male partners.

Thirteen (33.3%) studies specified or exemplified types of sexual practices according to the objectives of their study. As can be seen in Table 2, in these research participants were asked about sexual practices that included external genital contact, but in most cases the interest was focused on asking about the type of penetration in the intercourse, which shows no specific interest in real sex practices of WSW.

Sample traits according to interest in comprehensive sexual health in women who have sex with women (WSW).

| Interest on comprehensive sexual health in WSW | Sexual practices specification |

|---|---|

| Having male partners risk factor (Tat, 2015) | Genital-genital-digital-oral, toys, fisting, group, phone sex, bleeding (Wang, 2012) |

| Unplanned pregnancy, unsafe abortion (Zaidi, 2014) | Sexual Practices are different to sexual orientation, but not specified (Logie, 2014) |

| Transactional sex, sex with partners known to have STIs (Muzny, 2014) | Group sex (Muzny, 2014) |

| Male partners and individual factors (Muzny, 2014) | Rubbing, vaginal fingering, scissoring, cunnilingus, vibrators use (Schick, 2012) |

| Safer sex methods used by WSW (Schick, 2012) | Oral-vaginal-anal, penetration (fingers, toys), vaginal douching (Bailey, 2004) |

| Use of lubricants (Bailey, 2004) | Oral-vaginal/anal, digital-vaginal/anal (Marrazo, 2000) |

| No male partners reduce HPV screening (Marrazo, 2000) | Related to safer risk practices: latex gloves, dental dam, others (Fishman, 2003) |

| Perception of HIV risk and resources about safer sex (Fishman, 2003) | Oral sex, digital, sex toy stimulation and penetration (Rowen, 2013) |

| Sexual partners, importance of number and type (Mulllinax, 2016) | Sex toys, fingers/hands (Marrazzo, 2005) |

| Mental health and sexual health related to STD (Reisner, 2010) | Oral-vaginal sex, oral-anal, sharing vaginal sex toys, digital-vaginal (Forcey, 2015) |

| Barriers, pleasure, knowledge, testing as a prevention tool (Doull, 2018) | Oral sex, fingering, vaginal grinding, bumping (Muzny, 2013) |

| Factors intra/interpersonal, structural (Logie, 2015) | Sex toys, bleeding (Wang, 2012) |

| Barrier methods use (Muzny, 2013) | Sexual behaviors: hands, fingers, oral, anal sex, genital contact, toys (Fujji, 2019) |

| Barrier methods according to relationships type (Rowen, 2013) | |

| Marginalization and its repercussion in sexual health (Logie, 2012) | |

| Hygiene methods (Marrazzo, 2005) | |

| Risk perceptions, health-seeking behavior (Fish, 2005) | |

| Barriers with professionals, risk perception, safer sex (Silberman, 2016) | |

| Safer sex behaviors (Muzny, 2013) | |

| Helath dispatities (Singh, 2011) | |

| Web site safer sex with risk reduction alternatives (Cox, 2009) | |

| Perception of risk (Eaton, 2008) | |

| Psychosocial factors and STI prevention (Champion, 2005) | |

| Practitioners attitudes to disclosure (Rufino, 2018) | |

| Preventive behaviors and feelings (Fujji, 2019) |

The present scoping review aimed to assess the research gaps in the WSW considering the life cycle, prevention, recommendations for health teams and feminist approaches.

The included studies approached from multiple disciplines, providing future fields of research covering the entire life cycle, diverse sexual practices, and socially focused interventions in public health prevention from health teams. It is noteworthy that in studies focused on other populations such as MSM, in sexual health, the type of partners referred to are usually stable couples, friends, colleagues, which is not the case for women.23 It would be worth considering whether the former perpetuates the heteronormative model of health care for this group of women, hence placing them on a level of inequality within the rest of the population.24 The studies that referred to comprehensive sexual health were focused on the perception of risk in safer sex behaviours.24 Interests was found in structural factors (inter-personal, intra-personal and psychosocial), which sheds more light on possible factors that can determine comprehensive sexual health25 and health inequalities.26

Surprisingly, only slightly over half of the selected studies contribute ideas of sexual health from an integral point of view and that it tends more to approach it from a negative point of view (deficit, pathology). Indeed, when the analysis of information related to psychosocial aspects is incorporated these are considered risk factors for the appearance of diseases.27

On the other hand, no studies focused on older WSW have been found, being the limit age 55 years old. This restriction can lead to the invisibility of health problems in these women, risks and limitation of access to social and health services.

When analyzing the populations that are part of the studies, it was observed that there is no impact on sexual health in childhood and adolescence either, which leads to ignore at what age WSW understand the risk of STIs or why they choose not to use barriers when they have sexual relations.28,29

The constant equation of sexual orientation with sexual practices is also observed, concepts that are very rarely differentiated.30 This fact supposes an error already described in the health literature which leads to problems in the way in which the results of the epidemiological studies are provided, but also in prevention and health promotion interventions and that is reflected in healthcare practice.31 In this sense, Muzny et al.29 underline the need for a greater research on the effectiveness of recommendations about the use of barrier methods for STIs transmission reduction in WSW.

Other recommendations aimed at health providers, research and prevention, include taking into account female partners,19 the need for a change in care approaches,32 taking into account psychosocial factors,27 or integrating in the curricula of health sciences degrees the specificity of WSW sexual health needs.24 An important aspect highlighted is that sexual health must be addressed from childhood, thus underlining the importance of the life cycle approach in lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans and intersex people and the need to include sexual orientation in studies.33

Regarding the existence of a feminist approach in studies, we found some works criticizing the approach to certain sexual health problems, such as the transmission of HIV mainly in men.34 These works also show the need for keeping in mind the application of specific health care and specific sexual practices of WSW independently considered avoiding studies from a pathologizing pathological point of view or in comparison with other population groups and other women,30 as well as the importance of an intersectional vision, which accounts for the diversity of WSW.35

To the best of our knowledge this is the first scoping review examining the gaps in sexual health research about WSW. Nonetheless, as a limitation we have to state that the present study did not consider other types of documents beyond scientific journals, such as those mentioned above or doctoral theses, therefore articles with health professional's opinions on sexual minorities, prevalence estimations of sexual minority populations, studies with migrants or refugees, conference abstracts, case studies, and reports in the gray literature were excluded.

ConclusionsSeveral shortcomings about sexual health in WSW still exist. Due to the heterogeneity of the studies, mostly cross-sectional and without a follow-up for the specification of indicators such as incidence, as well as the diversity of populations recruited (WSW and WSWM), it is difficult to draw a general conclusion about the STIs in WSW.

Recommendations from a comprehensive sexual health approach in WSW should consider the improvement of specific self-care for WSW, education of health providers, and a life cycle and diversity centered perspective. These findings contribute to future research about sexual practices and sexual health care in WSW.

The absence of published data on the health problems affecting WSW sexual health perpetuates the heteronormative model of health care for this group of women, which places them on a level of inequality compared to other populations.

Authorship contributionsB. Obón-Azuara: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; planning, collected data,reporting of the work described in the article, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. C. Vergara-Maldonado: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, collected data,analysis or interpretation of data for the work; reporting of the work described in the article, final approval of the version to be published, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content, upload files to review. I. Gutiérrez-Cía: collected data, analysis, interpretation of data for the work. I. Iguacel Azorín: traduction, interpretation of data for the work and analys. A. Gasch-Gallén: substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, collected data, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; conduct, reporting of the work described in the article, final approval of the version to be published, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content. A. Gasch-Gallén and C. Vergara-Maldonado: responsibles for the overall content as guarantors.

There is a lack of knowledge about sexual health at the women who have sex with women (WSW), leading to confusion about the frequency of sexually transmitted infections. There are few studies addressing comprehensive sexual health at WSW and sexual orientation is commonly confused with sexual practice. Studies are still focused on sexually transmitted infections in populations at risk and there are several gaps about self-cares and specific interventions on sexual health promotion in WSW.\

What does this study add to the literature?This study is the first to assess the research gaps in the women who have sex with women (WSW) considering the life cycle, prevention, recommendations for health professionals and feminist approaches. This research provides future fields of research on WSW sexual health, covering the entire life cycle, including diverse sexual practices and socially focused interventions in public health prevention programs and for health professionals training.

What are the implications of the results?These results show the urgency of incorporating the specificities of the sexual health of women who have sex with women in clinical practice and in the design of public health campaigns, from a comprehensive approach, differentiating between sexual practices and affective-sexual orientations.

Azucena Santillán-García.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

AcknowledgementsIn memoriam of Concepcion Tómas Aznar (Professor of the Department of Physiatrics and Nursing, Nursing Area, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Zaragoza), for the inspiration space.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.