The objective of this study was to conduct a comparative analysis of the characteristics, indicators and strategies implemented by the programs of the four countries affiliated with the Ibero-American Network of Post-Consumer Medication Programs (RIPPM by its acronym in Spanish), identifying best practices and opportunities for improvement. To this end, we collected and analyzed information related to the operation of programs for the management of expired medications (EM) and household leftovers, based on official sources and publicly available data from the RIPPM member programs. A comparative analysis was conducted on the organizational structure, coverage indicators and implementation strategies, with data reported between 2017 and 2023. In the past decade, RIPPM has managed and eliminated more than 66,000 tons of EM, with the majority (89.7%) in Spain and Portugal. In these two countries, the territorial coverage is practically complete, with the participation of the pharmaceutical industry in the entire process (reverse logistics), non-existent in Latin America. Mexico presents the lowest levels of coverage and collection containers per 100,000 inhabitants, while Colombia reports the lowest average rates of collected tons and grams per inhabitants. We conclude that EM and leftovers in the American countries, present a higher potential for environmental contamination. RIPPM offers the opportunity to identify experiences and good practices for EM and leftover medication management, which could be implemented in Latin American countries, oriented towards circular and sustainable models, with complete territorial coverage and responsible participation of the pharmaceutical industry, fostering education and citizen participation as strategic axes.

El objetivo de este estudio fue realizar un análisis comparativo de la estructura, los indicadores y las estrategias implementadas por los programas de los cuatro países adheridos a la Red Iberoamericana de Programas Posconsumo de Medicamentos (RIPPM), identificando las mejores prácticas y oportunidades de mejora. Para ello, se llevó a cabo la recolección y el análisis de información relacionada con el funcionamiento de los programas de gestión de medicamentos caducos (MC) y sobrantes de los hogares, a partir de medios oficiales y datos de libre acceso de los programas que integran la RIPPM. Analizamos comparativamente la estructura organizativa, los indicadores de cobertura y las estrategias de implementación, con datos reportados entre 2017 y 2023. En la última década, la RIPPM ha gestionado y eliminado más de 66.000 toneladas de MC, la mayor parte (89,7%) en España y Portugal. En estos dos países, la cobertura territorial es prácticamente completa, con la participación de la industria farmacéutica en todo el proceso (logística inversa), inexistente en Latinoamérica. México presenta los niveles más bajos de cobertura y de contenedores de recogida por 100.000 habitantes, y Colombia las menores tasas promedio de toneladas recogidas y gramos por habitante. Podemos concluir que los MC y sobrantes en los países americanos presentan mayor potencial contaminante. La RIPPM ofrece la oportunidad de identificar experiencias y buenas prácticas, que podrían ser implementadas en países latinoamericanos, orientándose hacia modelos circulares y sostenibles, con cobertura territorial completa y la participación responsable de la industria farmacéutica, fomentando la educación y la participación ciudadanas como ejes estratégicos.

In Latin America, it is common for households to store leftover medications from previous treatments or non-prescribed drugs for minor ailments in family medicine cabinets.1–3 Studies show that incorrect disposal practices are also widespread, with medicines being mostly discarded in household waste (66-83%) or flushed down the toilet (11-30%).1,2 This behavior is related to limited environmental awareness and a lack of knowledge.2,3 In general, safe disposal strategies in this region are still in the initial stages of implementation.1 Current procedures, including wastewater treatment, are not equipped to degrade the active pharmaceutical ingredients that may pollute the environment.4,5

In line with the significance of this issue, the European Union (EU) has made substantial progress in regulating and managing pharmaceutical waste. Its intersectoral strategies include not only control and safe disposal but also educational programs, rational use of medicines, and stricter control of over-the-counter sales.5 In addition, the EU maintains surveillance of highly hazardous pharmaceutical and chemical compounds, has set concentration limits for some of them in receiving water bodies, and promotes improvements in wastewater treatment.5

Concerning the same environmental problem, the Ibero-American Network of Post-Consumer Medication Programs (RIPPM, by its Spanish acronym) was established in 2015, composed of Blue Point Corporation (CPA) in Colombia, the National System for the Management of Medication and Packaging Waste (SINGREM) in Mexico, the Integrated System for the Management of Medication Waste (SIGRE) in Spain, and Valormed in Portugal. All of them are national entities responsible for collecting and disposing of expired and leftover medications from households.6

The objective of this study is to analyze the structure, procedures, strategies, and key indicators of the programs that comprise the RIPPM through a comparative analysis aimed at identifying challenges, opportunities for improvement, and best practices that other countries could replicate.

MethodWe carried out a documentary review, collecting and analyzing data available through official sources and direct communication with the RIPPM programs, covering the period from 2017 to 2023. The procedures followed are detailed below.

Collection of publicly available dataInformation was gathered from the websites of the four programs,7–10 following a framework specifically designed for this study, which includes structural characteristics (program origin, legal framework, financing, and stated strategies), operational processes (mechanisms for collection, transportation, storage, classification, statistical data recorded, and final disposal procedures), and performance indicators:

- •

Valormed (Portugal) publishes annual activity reports and biannual indicators, general program descriptions, operating licenses, management processes, campaigns, and current news (sections: “About Us”, “How We Operate”, “Campaigns” and “News”).

- •

CPA's web page (Colombia) contains the 2017 sustainability, social responsibility, and transparency report, the human medication post-consumer plan, public campaigns from 2017 to 2020, and a program history (sections: “About Us”, “Our Services” and “A Happy Planet”).

- •

SIGRE (Spain), the 2023 sustainability report, the Pharmaceutical Industry Prevention and Ecodesign Business Plan (PEPE 2024–2028), and information on its organization, operations, ecodesign, sustainability, campaigns, and past reports were consulted (sections: “Who We Are”, “Sustainability” and “Communication”).

- •

SINGREM (Mexico), yearly cumulative collection data (available until 2017), legal framework, operational model, and information on safe containers (sections: “Who We Are” and “Safe Containers”).

When relevant data searched were unavailable publicly, we sent direct requests for information via email to the operational and public service areas of each program. For SINGREM, the data on indicators, operations, and waste management included in this study were provided by the General Directorate of the program, updated to 2022. SIGRE also shared its historical collection data (2014–2023). No direct response was received from CPA regarding information on its budget, updated collection data, and final waste disposal.

Data analysisWe created comparative tables in accordance with the logical sequence of the data collection and analysis framework described above. As the information from the four programs differed in format and presentation, units of measurement were standardized to ensure that percentages, rates, and ratios were comparable. The information was processed using Microsoft Office 365.

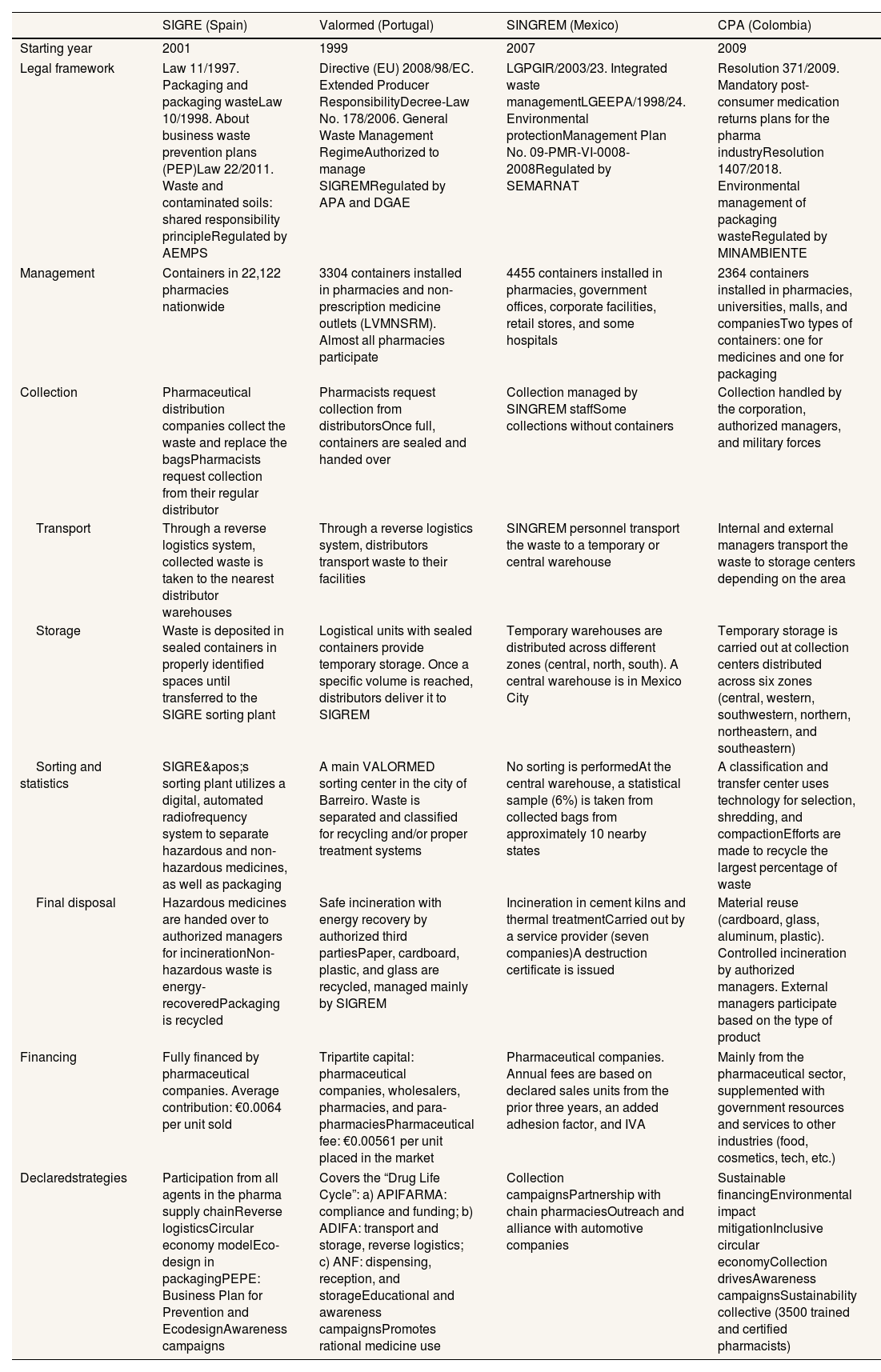

ResultsStructural and operational differences among RIPPM programs (Table 1)Environmental authorities oversee the operation of RIPPM programs in compliance with national regulations that vary from country to country. In Portugal, Spain, and Colombia, pharmaceutical companies are required to contribute with resources and/or actively participate in the program management processes. In contrast, in Mexico, participation is voluntary, and members contribute only with funding. All four programs have implemented a common mechanism whereby each pharmaceutical company pays a fee proportional to the volume of medications sold.

Structural characteristics and general description of the processes for collecting, storing, and final disposal of medicines and packaging in the countries of the Ibero-American Network of Post-Consumer Medication Programs (RIPPM).

| SIGRE (Spain) | Valormed (Portugal) | SINGREM (Mexico) | CPA (Colombia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting year | 2001 | 1999 | 2007 | 2009 |

| Legal framework | Law 11/1997. Packaging and packaging wasteLaw 10/1998. About business waste prevention plans (PEP)Law 22/2011. Waste and contaminated soils: shared responsibility principleRegulated by AEMPS | Directive (EU) 2008/98/EC. Extended Producer ResponsibilityDecree-Law No. 178/2006. General Waste Management RegimeAuthorized to manage SIGREMRegulated by APA and DGAE | LGPGIR/2003/23. Integrated waste managementLGEEPA/1998/24. Environmental protectionManagement Plan No. 09-PMR-VI-0008-2008Regulated by SEMARNAT | Resolution 371/2009. Mandatory post-consumer medication returns plans for the pharma industryResolution 1407/2018. Environmental management of packaging wasteRegulated by MINAMBIENTE |

| Management | Containers in 22,122 pharmacies nationwide | 3304 containers installed in pharmacies and non-prescription medicine outlets (LVMNSRM). Almost all pharmacies participate | 4455 containers installed in pharmacies, government offices, corporate facilities, retail stores, and some hospitals | 2364 containers installed in pharmacies, universities, malls, and companiesTwo types of containers: one for medicines and one for packaging |

| Collection | Pharmaceutical distribution companies collect the waste and replace the bagsPharmacists request collection from their regular distributor | Pharmacists request collection from distributorsOnce full, containers are sealed and handed over | Collection managed by SINGREM staffSome collections without containers | Collection handled by the corporation, authorized managers, and military forces |

| Transport | Through a reverse logistics system, collected waste is taken to the nearest distributor warehouses | Through a reverse logistics system, distributors transport waste to their facilities | SINGREM personnel transport the waste to a temporary or central warehouse | Internal and external managers transport the waste to storage centers depending on the area |

| Storage | Waste is deposited in sealed containers in properly identified spaces until transferred to the SIGRE sorting plant | Logistical units with sealed containers provide temporary storage. Once a specific volume is reached, distributors deliver it to SIGREM | Temporary warehouses are distributed across different zones (central, north, south). A central warehouse is in Mexico City | Temporary storage is carried out at collection centers distributed across six zones (central, western, southwestern, northern, northeastern, and southeastern) |

| Sorting and statistics | SIGRE's sorting plant utilizes a digital, automated radiofrequency system to separate hazardous and non-hazardous medicines, as well as packaging | A main VALORMED sorting center in the city of Barreiro. Waste is separated and classified for recycling and/or proper treatment systems | No sorting is performedAt the central warehouse, a statistical sample (6%) is taken from collected bags from approximately 10 nearby states | A classification and transfer center uses technology for selection, shredding, and compactionEfforts are made to recycle the largest percentage of waste |

| Final disposal | Hazardous medicines are handed over to authorized managers for incinerationNon-hazardous waste is energy-recoveredPackaging is recycled | Safe incineration with energy recovery by authorized third partiesPaper, cardboard, plastic, and glass are recycled, managed mainly by SIGREM | Incineration in cement kilns and thermal treatmentCarried out by a service provider (seven companies)A destruction certificate is issued | Material reuse (cardboard, glass, aluminum, plastic). Controlled incineration by authorized managers. External managers participate based on the type of product |

| Financing | Fully financed by pharmaceutical companies. Average contribution: €0.0064 per unit sold | Tripartite capital: pharmaceutical companies, wholesalers, pharmacies, and para-pharmaciesPharmaceutical fee: €0.00561 per unit placed in the market | Pharmaceutical companies. Annual fees are based on declared sales units from the prior three years, an added adhesion factor, and IVA | Mainly from the pharmaceutical sector, supplemented with government resources and services to other industries (food, cosmetics, tech, etc.) |

| Declaredstrategies | Participation from all agents in the pharma supply chainReverse logisticsCircular economy modelEco-design in packagingPEPE: Business Plan for Prevention and EcodesignAwareness campaigns | Covers the “Drug Life Cycle”: a) APIFARMA: compliance and funding; b) ADIFA: transport and storage, reverse logistics; c) ANF: dispensing, reception, and storageEducational and awareness campaignsPromotes rational medicine use | Collection campaignsPartnership with chain pharmaciesOutreach and alliance with automotive companies | Sustainable financingEnvironmental impact mitigationInclusive circular economyCollection drivesAwareness campaignsSustainability collective (3500 trained and certified pharmacists) |

ADIFA: Association of Pharmaceutical Distributors; AEMPS: Spanish Agency for Medicines and Health Products; AMIIF: Mexican Association of Pharmaceutical Research Industries; ANAFAM: National Association of Drug Manufacturers; ANF: National Association of Pharmacies; APA: Portuguese Environment Agency; APIFARMA: Portuguese Pharmaceutical Industry Association; CANIFARMA: National Chamber of the Pharmaceutical Industry; DGAE: General Directorate of Economic Activities; FEDIFAR: Federation of Pharmaceutical Distributors; IVA: Value Added Tax; LGEEPA: General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection; LGPGIR: General Law for the Prevention and Comprehensive Management of Waste; LVMNSRM: Points of Sale for Over-the-Counter Medications; MINAMBIENTE: Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development; SEMARNAT: Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources; SIGRE: Integrated System for the Management of Pharmaceutical Waste; SIGREM: Integrated System for the Management of Medication and Packaging Waste; SINGREM: National System for the Management of Medication and Packaging Waste.

Source: compiled by the authors based on official sources and information directly shared by RIPPM programs.

European strategies encompass primary source prevention, eco-design, responsible waste management, and public awareness initiatives. In contrast, programs in America prioritize collection coverage and financing.

In Europe, pharmacies collect medications and provide informational support to guide the public on proper disposal. In Mexico and Colombia, collection points have been expanded to public spaces without providing guidance for users.

European distributors collect waste in addition to supplying medications to pharmacies (reverse logistics) and temporarily store it before sending it to a sorting plant. In America, this task is performed by internal or external personnel utilizing proprietary warehouses. The final treatment depends on the type of waste and includes elimination or reuse, recycling, and energy recovery. In Mexico, all collected waste is incinerated, with no recovery.

In addition to funding, European pharmaceutical companies also supervise waste management and promote new packaging technologies to facilitate recovery. These programs have successfully integrated the entire pharmaceutical sector into the program's processes.

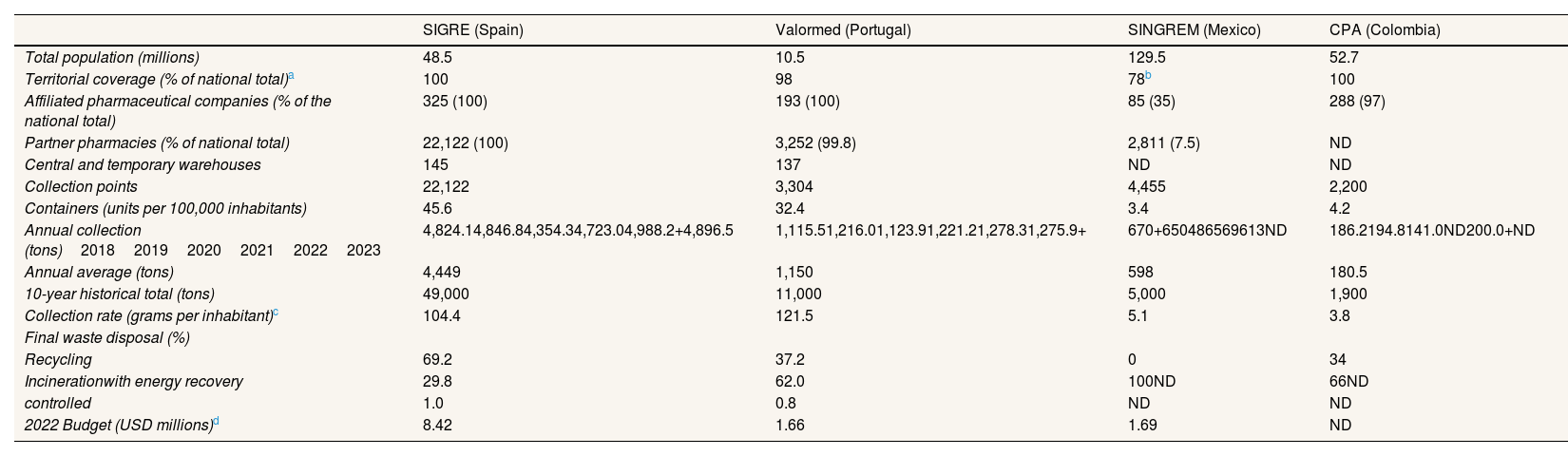

Performance indicator disparitiesTable 2 shows that SINGREM has the lowest territorial coverage, with only 7.5% of pharmacies in Mexico with collection containers, and the lowest pharmaceutical sector participation (35% of pharmaceutical firms). In contrast, the other three programs exceed 98% coverage and 97% participation.

Indicators of post-consumer medication programs and general data (latest reporting year: 2023).

| SIGRE (Spain) | Valormed (Portugal) | SINGREM (Mexico) | CPA (Colombia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population (millions) | 48.5 | 10.5 | 129.5 | 52.7 |

| Territorial coverage (% of national total)a | 100 | 98 | 78b | 100 |

| Affiliated pharmaceutical companies (% of the national total) | 325 (100) | 193 (100) | 85 (35) | 288 (97) |

| Partner pharmacies (% of national total) | 22,122 (100) | 3,252 (99.8) | 2,811 (7.5) | ND |

| Central and temporary warehouses | 145 | 137 | ND | ND |

| Collection points | 22,122 | 3,304 | 4,455 | 2,200 |

| Containers (units per 100,000 inhabitants) | 45.6 | 32.4 | 3.4 | 4.2 |

| Annual collection (tons)201820192020202120222023 | 4,824.14,846.84,354.34,723.04,988.2+4,896.5 | 1,115.51,216.01,123.91,221.21,278.31,275.9+ | 670+650486569613ND | 186.2194.8141.0ND200.0+ND |

| Annual average (tons) | 4,449 | 1,150 | 598 | 180.5 |

| 10-year historical total (tons) | 49,000 | 11,000 | 5,000 | 1,900 |

| Collection rate (grams per inhabitant)c | 104.4 | 121.5 | 5.1 | 3.8 |

| Final waste disposal (%) | ||||

| Recycling | 69.2 | 37.2 | 0 | 34 |

| Incinerationwith energy recovery | 29.8 | 62.0 | 100ND | 66ND |

| controlled | 1.0 | 0.8 | ND | ND |

| 2022 Budget (USD millions)d | 8.42 | 1.66 | 1.69 | ND |

ND: no data; SIGRE: Integrated System for the Management of Medication Waste; SINGREM: National System for the Management of Medication and Packaging Waste.

Territorial coverage in Mexico refers to the percentage of federal states covered; in Colombia, to the percentage of districts; in Spain and Portugal, to the percentage of pharmacies with collection service.

The figure refers to states where the program is present; it does not imply full coverage of the population or establishments in those states. States without SINGREM presence: Baja California (North and South), Sonora, Chihuahua, Tamaulipas, Tabasco, and Chiapas.

For the calculation, the year with the highest reported annual collection marked with (+) was used.

Average exchange rates in 2022 (investing.com): Mexican peso = 0.04995 USD; Euro = 1.0528 USD.

Source: compiled by the authors based on official sources and data directly provided by RIPPM programs up to 2023. Population data: Mexico, INEGI 2023; Colombia, DANE 2024; Spain, INE 2023; Portugal, World Bank 2023.

Spain has 45.6 containers per 100,000 inhabitants, followed by Portugal with 32.4, while Mexico and Colombia have approximately 4 units each. Regarding collection volume, European programs collect slightly more than 100 grams of medication per inhabitant, compared to 5 grams in Latin America. In absolute terms, SIGRE leads the way with an annual average of nearly 5,000 tons of expired medications. In 2022, its budget was four times that of its Mexican counterpart despite serving a population 2.6 times smaller and collecting eight times more. Additionally, the Spanish program excels in waste recovery, achieving a recycling rate close to 70%.

DiscussionPublic policy and regulation should be improvedIt is essential to have laws regulating the consumption, disposal, and reverse logistics of medications. The current situation remains deficient. Other countries in the region, such as Brazil, regulate manufacturing, distribution, and dispensing but do not address household disposal.3 Currently, there is no international standard for managing this problem.11 Mexico is the only RIPPM country where pharmaceutical companies’ participation is voluntary.

Moreover, even where regulation exists, enforcement and compliance are often weak and inconsistently applied.12 It is necessary to design public policies that approach the problem comprehensively,13 involving pharmaceutical companies and consumers, and incorporating environmental monitoring actions, as implemented in the EU.5

Organization, financing, and operational capacity must be strengthenedThe safe disposal of pharmaceuticals is often costly, and not all countries have the necessary resources. Diverse socioeconomic realities and heterogeneous levels of infrastructure and technology affect the scope of the initiatives.4 Big countries like Mexico and Brazil have not yet achieved complete coverage.1,11

Spain and Portugal have established strong alliances among the three key sectors in the pharmaceutical supply chain: pharmaceutical companies, distributors, and pharmacies. This scheme avoids the investment of public resources in transportation, storage, or specialized staff. Additional strategies worth noticing are investment in new technologies, improving processes’ efficiency (SIGRE), and providing waste management services to private companies, generating additional revenue (CPA).

While Colombia and Mexico have made notable progress compared to other Latin American countries, their efforts still fall short. Their limited resources are reflected in low performance and coverage.4 Strengthening technical capacities in coordination with the pharmaceutical industry is essential. Increased funding, government support, and corporate commitment could boost their development.

To reduce the environmental impact, programs must transition toward a circular economy and promote waste recovery. Although Spain has a smaller population than Mexico, it collects considerably more pharmaceutical waste, achieving high levels of recycling and energy recovery. This may be explained by four key factors: 1) a more comprehensive and effectively implemented regulation; 2) complete territorial coverage; 3) informative resources available to users in pharmacies; and 4) higher public environmental awareness. Reports indicate that 91% of Spaniards consider disposing of medications in the trash or down the toilet to be harmful to the environment.14

Community participation is a crucial factor in the success of any program. It should be a strategic axis in the design of public policies and health interventions, as well as in enhancing transparency.15 Educational programs, awareness campaigns, and pharmacy-based guidance have strengthened public awareness in Europe.

Ibero-American and regional collaboration is possible and desirableThe lack of harmonized regulation across the Latin American region hinders coordination and proper management of pharmaceutical waste. Within RIPPM, there is no single operational model due to socioeconomic, infrastructural, and awareness-level differences.4

RIPPM was created with clear objectives: to exchange experiences in pharmaceutical waste management, coordinate and innovate in the best disposal practices, and adapt programs to diverse cultural, geographic, social, economic, and regulatory contexts. Both regions can benefit from experience-sharing, especially as new members join.6

There is a global and RIPPM-level commitment to the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. This alignment promotes responsible resource use, access to funding, and international support.4 The challenge now is to ensure these goals are effectively fulfilled.

ConclusionsBeyond legal compliance, various strategies have been implemented to mitigate the environmental impact of expired and leftover medications. Programs in Spain, Portugal, and Colombia have progressed toward circular models that incorporate eco-design, innovation, process efficiency, and waste recovery, albeit to different extents. Mexico, on the other hand, is most in need of effective interventions.

The RIPPM represents an opportunity to promote comprehensive solutions, share best practices, and transition toward a sustainable circular economy in Latin America. Harmonizing regional regulations could enhance international cooperation. Promoting environmental awareness, community engagement, and full, non-voluntary participation by the pharmaceutical industry is essential to reducing environmental impact.

Pharmaceutical waste management becomes relevant for its environmental and health impact. Domestic disposal is commonly inadequate, although some Ibero-American countries already apply safe collection and treatment.

What does this study add to the literature?The study documents operational approaches and identifies good practices and areas for improvement. Key evidence to strengthen regional articulation.

What are the implications of the results?The findings may guide public policies, promote regional cooperation and offer tools for better sustainable waste management with more solid health and environmental governance.

Salvador Peiró.

Authorship contributionsR. Quiroz Razo collaborated in the conception of the article, the compilation and data analysis, draft writing and design of the work, and the guarantee that all parts of the text have been revised and discussed among the authors.

P.J. Saturno-Hernández collaborated in the general supervision, final writing and design of the work, critical revision of the content and final approval of the manuscript.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.