The 3rd International Nursing and Health Sciences Students and Health Care Professionals Conference (INHSP)

More infoThe study aims to compare levels NO, the ROT, and BMI values in preeclampsia and normotension.

MethodThis study was an observational analytical study that combined the draft case–control study and a cross-sectional study (hybrid method) conducted in February–June 2020. This study was conducted in the Hospital Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Makasar, Antang Health Center, Barabaraya Health Center, and Mamajang Health Center. Respondents in this study were pregnant women divided into two groups, 108 mothers with normal pregnancies and 42 mothers with preeclampsia. The criteria of the study respondents were single pregnancies, pregnancy of more than 20 weeks, and the gestational age of 20–35 years old. Data collected includes age, parity, gestational age, pregnancy interval, body mass index (BMI), and education. In addition, Nitric oxide levels are determined using Elisa Kit, and roll over test is collected by performing blood pressure measurements at two different positions.

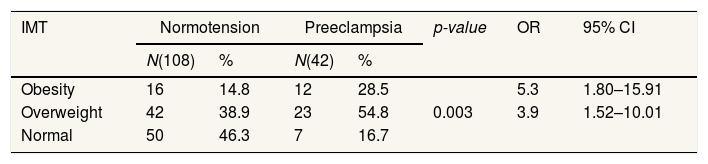

ResultsThe mean serum NO levels in the preeclampsia 176.43±50.8 and 152.75±51.3 in normotension, and there is a meaningful relationship p=0.012. Mean value of ROT in preeclampsia 23.21±8.54 and 19.63±8.85 in normotension p=0.026. There is a meaningful difference in IMT with preeclampsia p=0.003.

ConclusionNO, ROT and BMI are significantly higher in pregnant mothers with preeclampsia than in normal pregnancies.

Every day in 2015, about 830 women died from pregnancy and childbirth complications which are largely preventable. Maternal mortality is nearly 75% due to complications of bleeding, infection, hypertension during pregnancy, including preeclampsia and eclampsia, childbirth complications, and unsafe abortions.1 In Indonesia based on maternal mortality rate reached 305/100,000 live births. The leading causes of death are bleeding, hypertension in pregnancy, and infections.2

Preeclampsia is the leading cause of restrictions on fetal growth, premature childbirth, and maternal deaths worldwide. The underlying pathology of preeclampsia may be due to the relative hypoxia or ischemic placenta. Preeclampsia is a specific pregnancy syndrome mainly associated with reduced organ perfusion due to vasospasm and endothelial activation.3,4 Other preeclampsia-related factors include obesity, double pregnancy, too old or young age, pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, or hypertension.5,6 The risk of preeclampsia is higher in obesity than overweight. Obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia by as much as 2.47-fold.7

Roll over test (ROT) is a measurement of blood pressure at two different positions, namely on the left side sleep position and the position of the sleep is stretched. The mother's position greatly affects the hemodynamic profile of the mother and fetus.5 The disruption of the flow of Uteroplasenta causes the change in the value of hemodynamic profile between mother and fetus as blood pressure increases.8 The results of the study conducted by Ghojazadeh9 stated that significantly the value of the roll over positive test was higher in the Preeclampsia mother group.

Preeclampsia clinical syndrome is thought to occur due to the widespread changes in endothelial cells. An intact endothelial has anticoagulant properties, and endothelial cells dull the smooth muscle response of blood vessels against the agonist by releasing nitric oxide; damaged or activated endothelial cells can produce less nitric oxide and purify substances that spur coagulation, as well as increase sensitivity to vasopressor.5 NO serves as the main transmitter for endothelium regulation that relies on vascular tone controlled by the humoral, metabolic, and mechanical factors, for example, in response to increased blood flow.10 In particular, NO is the primary vasodilator involved in regulating the reactivity of placental veins, placental vascular resistance, trophoblast invasion and apoptosis, and the adhesion and platelet aggregation in the intervillous chambers.11 The study results conducted by Hodzic et al.,12 concluded that NO's production decreased on preeclampsia, indicating that NO can modulate cardiovascular changes during pregnancy is complicated by preeclampsia. Inversely proportional to the study of Darkwa et al.,13 concluded that nitric oxide levels might not play an important role in preeclampsia etiology. It is still a contradiction of the etiology of preeclampsia. The study aims to compare levels NO, the ROT, and IMT values in preeclampsia and normotension.

MethodResearch siteThe research was conducted in February–June 2020 and received an ethical pre-objective recommendation with the protocol number UH19111028. This study was conducted in the hospital Dr. Wahidin Sudirohusodo Makassar, Health center Bara Baraya, Health center Antang and Health center Mamajang.

Data types and sourcesData from the samples are demographic data of age, parity, gestational age, pregnancy interval, weight, height, preeclampsia history, education. Data were taken from normotension and preeclampsia in pregnant mothers aged 20–30 years old and more than 20 weeks gestational age.

Data collection techniquesData collection using questionnaires related to the respondent's demographic data through a direct interview with the respondent. To measure blood pressure in assessing roll over test, used Spignomanometer. Subsequent blood sampling to measure nitric oxide (NO) levels, researchers were assisted by laboratory personnel. The collected samples were then Disentrifius and kept in the refrigerator at −20°C. After all the samples were fulfilled, NO serum levels were examined using Nitric Oxide Microplate Assay Kit, MyBioSource at the Hasanuddin University Medical Research Center (HUM-RC) Laboratory.

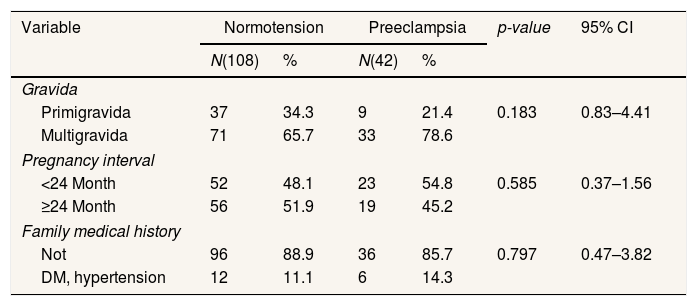

ResultsTable 1 shows that there is no significant difference between pregnancy interval, gravida and family medical history of disease between normotensive pregnant women and pregnant women with preeclampsia. So this shows that the sample in this study is homogeneous.

Respondent demographic characteristics.

| Variable | Normotension | Preeclampsia | p-value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(108) | % | N(42) | % | |||

| Gravida | ||||||

| Primigravida | 37 | 34.3 | 9 | 21.4 | 0.183 | 0.83–4.41 |

| Multigravida | 71 | 65.7 | 33 | 78.6 | ||

| Pregnancy interval | ||||||

| <24 Month | 52 | 48.1 | 23 | 54.8 | 0.585 | 0.37–1.56 |

| ≥24 Month | 56 | 51.9 | 19 | 45.2 | ||

| Family medical history | ||||||

| Not | 96 | 88.9 | 36 | 85.7 | 0.797 | 0.47–3.82 |

| DM, hypertension | 12 | 11.1 | 6 | 14.3 | ||

Chi-Square.

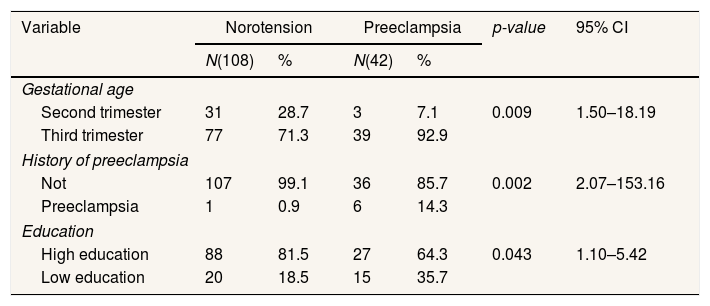

Table 2 shows that gestational age has a significant relationship with the incidence of PE, namely p=0.009; 95% CI=1.50–18.19. There was a significant difference in the history of preeclampsia with p value=0.002; 95% CI=2.07–153.16. There is a significant difference in education, namely p=0.043; OR=2.4; 95% CI=1.10–5.42.

Moderator variable frequency distribution analysis.

| Variable | Norotension | Preeclampsia | p-value | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N(108) | % | N(42) | % | |||

| Gestational age | ||||||

| Second trimester | 31 | 28.7 | 3 | 7.1 | 0.009 | 1.50–18.19 |

| Third trimester | 77 | 71.3 | 39 | 92.9 | ||

| History of preeclampsia | ||||||

| Not | 107 | 99.1 | 36 | 85.7 | 0.002 | 2.07–153.16 |

| Preeclampsia | 1 | 0.9 | 6 | 14.3 | ||

| Education | ||||||

| High education | 88 | 81.5 | 27 | 64.3 | 0.043 | 1.10–5.42 |

| Low education | 20 | 18.5 | 15 | 35.7 | ||

Chi-square.

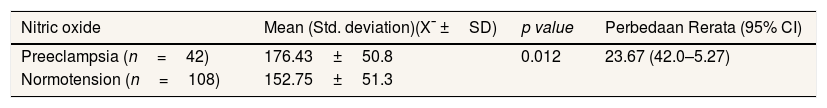

Table 3 shows that the mean NO levels in preeclampsia were higher than normotensive, namely 176.43±50.8 in preeclampsia and 152.75±51.3 in normotensive. From the results of statistical tests there is a significant difference with p=0.012.

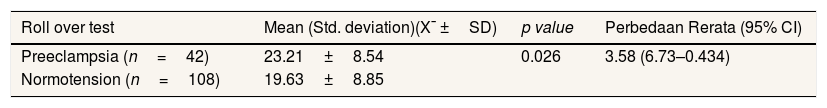

Table 4 shows that the mean ROT for normotensive pregnant women is lower than pregnant women with preeclampsia, namely 19.63±8.85 for normotensive and 23.21±8.54 for preeclampsia. From the results of statistical tests there is a significant difference with p=0.026.

Table 5 shows that there is a significant difference in BMI with p value=0.003. BMI of obese pregnant women OR=5.9; 95% CI=1.52–10.01 and BMI of overweight pregnant women OR=3.9; 95% CI=1.80–15.91. This means that pregnant women with an obese BMI are 5.9 times more likely to develop preeclampsia than pregnant women with an overweight BMI 3.9 times and pregnant women with a normal BMI.

DiscussionTable 1 shows parity; there is no significant relationship with preeclampsia. In line with the study of Ahmed et al.,14 shows parity, there is no meaningful difference between normotension and preeclampsia. Berhe et al.,15 also get the results that there is no significant link between the Primi and multiparity with hypertension in pregnancy. This happens because parity gives a different effect to any expectant mothers who experience hypertension in pregnancy. In addition to parity, pregnancy interval and family history of illness do not indicate a meaningful difference between normotension and preeclampsia. This is in line with the study of Yuniarti et al.,16 that the interval of pregnancy and the history of family illness has no significant relationship with the occurrence of preeclampsia. Inversely proportional to Rahmawati17 stated that the family history of the disease is significantly related to preeclampsia. Another risk factor associated with preeclampsia is a history of family diseases.18

The gestational age indicates a significant relationship to the incidence of preeclampsia (Table 2). In the results of this study, the gestational age is more common in late-onset preeclampsia than early onset. This is in line with the study conducted by Gasse19 that one of the mother's characteristics is the age of pregnancy is a predictor in the incidence of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia is more commonly found in pregnant women who have a history of preeclampsia/eclampsia.5,20 Based on statistical tests, Preeclampsia is a significant relationship with preeclampsia. This is in line with Rocha21 that the history of Preeclampsia has a significant relationship with preeclampsia. The risk of preeclampsia increased seven times in women who had previous preeclampsia history.7 Preeclampsia is more commonly found in pregnant women who have a history of preeclampsia/eclampsia.5,20 Based on statistical test results, education demonstrates a significant relationship with the incidence of preeclampsia. It is in line with Nasr et al.,22 that there is a significant correlation between education and hypertension in pregnancy. Education relates to the opportunity to absorb information on the prevention and factors of preeclampsia. High or low education also does not guarantee to avoid certain diseases. But education is also influenced by motivation and environmental support to apply preeclampsia prevention efforts.

Table 3 shows NO significant differences in preeclampsia and normotension groups. But the mean serum NO levels in the preeclampsia is higher than that of normotension. The results of these studies do not appear to be in accordance with the general phenomenon of preeclampsia, where NO as a proper Vasodilatator substance will decrease the rate of preeclampsia. The study results of Susiawaty et al.,23 stated that patients with preeclampsia have an expression value of nitric oxide higher than normal pregnancies. This may still be the compensation phase of preeclampsia or the early phases of the journey toward eclampsia. Smarason et al.,24 also argue that the NO levels in preeclampsia are higher than normal pregnancies caused by unknown sources or decreased elimination through the kidneys. These findings can explain that foodstuffs consumed with high nitrate content, such as cured meats or vegetables, are sources of exogenous nitrates. The study results by Hodzic et al.12 concluded that NO production increased with the age of pregnancy during normal pregnancy and decreased on preeclampsia, indicating that NO can modulate cardiovascular changes during normal pregnancy and pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia. In line with Bhatnagar et al.,25 Preeclampsia is a multiracial etiopathological disease, NO may play an important role in the development of preeclampsia. However, this is inversely proportional to the results of the study done by Darkwa et al.,13 that NO levels may not play an important role in the etiology of preeclampsia.

The lower the NO blood level, the higher the systolic and diastolic blood pressure because NO is a vasodilatory compound. The worsening of endothelial damage caused by excessive oxidative stress, NO production will be lower, blood pressure increased, and preeclampsia. In short, NO production increases with increasing gestational age during normal pregnancies and decreases preeclampsia, regardless of serum concentrations of ferritin. NO concentration increases during pregnancy returns to normal in 12 weeks after childbirth.26 This substance is also produced by the endothelial fetus, and its degree increases in response to preeclampsia, diabetes, and infections.5 Preeclampsia is a specific pregnancy syndrome that is mainly related to the reduction of organ perfusion due to vasospasm and endothelial activation, which manifests in the presence of increased blood pressure and proteinuria.3,6

Table 4 shows a meaningful difference between the ROT and preeclampsia. The mean value of ROT in preeclampsia is higher than that of the normotension. The study results conducted by Ghojazadeh9 that BMI, education, and the positive ROT can predict preeclampsia. In line with Suprihatin and Norontoko27 also stated that the combination of IMT, ROT, and MAP predictors effectively predicts preeclampsia. In general, pregnant women will undergo physiological, hematological changes. There is a profound effect between the mother's position on the hemodynamic profile of the mother and fetus. In the position of the pressure of the lower vein cava inferior (VCI) led to a reduction in the venous backflow to the heart and decreased volume of stroke and cardiac output. Turning from the lateral to the stretch position can decrease heart rate by 25%, disrupting the blood flow of the Uteroplasenta.8 The disruption of the flow of Uteroplasenta causes the change in the value of hemodynamic profile between mother and fetus as blood pressure increases.8 The incidence of hypertension response to the change in the position of expectant mothers 28–32 weeks from skewed to supine is the predictor of gestational hypertension. Expectant mothers with positive tests also show abnormal sensitivity to angiotensin II. In preeclampsia, changes in physiology in the uteroplacental arteries do not pass through the desiduamiometrial junction so that there is a narrowed segment between the radial arteries and decidua.28

The body mass index demonstrates a significant relationship to the incidence of preeclampsia (Table 5). BMI expectant mothers of obesity are prone to preeclampsia compared to the BMI of overweight or normal pregnant mothers. In line with the research, Reslan and Khalil29 Declare that pregnant women with a BMI of obesity are at risk five times greater to suffer preeclampsia compared with pregnant women with normal BMI. Rocha et al.,21 also supported this outcome where the IMT had significant connections with preeclampsia. Obesity increases the risk of preeclampsia by as much as 2.47-fold.7 The relationship between mom's weight and preeclampsia risk is progressive. This risk increased from 4.3% in women with a BMI of <20kg/m2 to 13.3% in women with a BMI>35kg/m2.5 Excess weight and obesity can be regarded as a predictor.30 Mechanisms in which excess IMT causes preeclampsia may not be well understood, but there are several mechanisms describing preeclampsia pathogenesis, a strong link between obesity and insulin resistance resulting in gestational diabetes and type II diabetes mellitus. Both are associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia.31,32 On the other hand, a metabolic syndrome characterized by obesity is associated with endothelial dysfunction, where endothelial dysfunction is one of the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.33 Preeclampsia is influenced by factors of maternal illness, including heart or kidney disease, diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, or hereditary diseases.5

ConclusionIn this study, NO levels, score of ROT, and BMI value were significantly higher in pregnant women with preeclampsia compared to normal pregnancies.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the 3rd International Nursing, Health Science Students & Health Care Professionals Conference. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.