Providing a general overview of the European Union's health workforce mobility under the challenges facing health systems regarding the supply of health workers.

MethodWe use a descriptive method, based on the analysis of secondary data, qualitative and quantitative, concerning the European Semester from the European Union, complemented with statistical data from both the Union and some international organisations.

ResultsThe mobility of health professionals in the Union, associated to strong reliance on recruiting abroad and shortages due to emigration, was identified as a challenge in the European Semester process in a significant number of times during 2017-2023. The pandemic aggravated pre-existing shortages and the need to strike a balance between maintaining the resolution capacity of health systems while abiding by the free movement of health professionals. The information shows that Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Lithuania, Latvia, Portugal, Bulgaria, Greece, Croatia, Hungary, Italy, and Slovenia could be flagged with an “issuer profile”. Luxembourg, Ireland, Malta, and Sweden could be flagged with a “recipient profile”. We benefited from improvements in the information system concerning the Union's health workforce. Further advances regarding the harmonisation of health professions’ definition are needed, especially for nurses.

ConclusionsThe European Union faces internal migrations of health professionals. Mobility is used as a solution to shortages. The pandemic aggravated pre-existing shortages bringing to the forefront the need to strike a balance between health objectives and internal market objectives. Member States are immersed in health reforms, some financed with European Funds. Promoting health workforce planning and forecasting would emerge as a necessary action, including improving harmonised information. Drawing in a systematic way on the available information from the European Semester reports may provide some clues to give answers to policymaking concerning health professionals’ mobility.

Proporcionar una visión general de la movilidad del personal sanitario de la Unión Europea ante los desafíos a los que se enfrentan los sistemas sanitarios relacionados con la oferta de profesionales.

MétodoUtilizamos un método de investigación descriptivo, basado en el análisis de información secundaria, cualitativa y cuantitativa, relativa al Semestre Europeo de la Unión Europea, complementada con datos estadísticos tanto de la Unión Europea como de algunas organizaciones internacionales.

ResultadosLa movilidad de los profesionales sanitarios en la Unión Europea, asociada a problemas de fuerte dependencia de la contratación de profesionales extranjeros y escasez debido a la emigración, se identificó como un desafío en el proceso del Semestre Europeo en un número significativo de veces durante el periodo 2017-2023. La pandemia agravó la escasez preexistente, enfatizando la necesidad de lograr un equilibrio entre mantener la capacidad resolutiva de los sistemas sanitarios y respetar al mismo tiempo la libre circulación de los profesionales sanitarios. La información muestra que Rumanía, Eslovaquia, España, Lituania, Letonia, Portugal, Bulgaria, Grecia, Croacia, Hungría, Italia y Eslovenia se podría considerar que tienen un «perfil emisor». Luxemburgo, Irlanda, Malta y Suecia tendrían un «perfil receptor». Algunas mejoras registradas en el sistema de información sobre recursos humanos en el sector sanitario de la Unión Europea han resultado útiles. Sería preciso realizar más avances en la armonización de la definición de profesiones sanitarias, especialmente para la enfermería.

ConclusionesLa Unión Europea se enfrenta a migraciones internas de profesionales sanitarios. La movilidad se utiliza como solución a la escasez. Parece que la pandemia agravó la escasez preexistente, poniendo en primer plano la necesidad de las autoridades sanitarias de lograr un equilibrio entre los objetivos sanitarios y los objetivos del mercado interior. Los Estados miembros están inmersos en reformas sanitarias, algunas financiadas con Fondos Europeos. Promover la planificación y la previsión del personal sanitario sería una acción necesaria, incluida la mejora de la información armonizada. Además, extraer de forma sistemática la información disponible de los informes del Semestre Europeo proporcionaría claves para dar respuestas a la formulación de políticas sobre movilidad de los profesionales sanitarios.

Key points

- •

The mobility of health professionals in the EU, which is associated to the issues of strong reliance on recruiting abroad and facing shortages due to emigration of professionals, has been identified as a challenge in the ES process in a significant number of times during the period 2017-2023.

- •

The COVID-19 pandemic has aggravated pre-existing shortages thus bringing to the forefront the need to strike a balance between health objectives and internal market objectives.

- •

Mobility as a solution to shortages is also a threat to the planning and delivery of services, thus planning and forecasting appears as a relevant policy tool at national and EU level that would require further improvement of the information systems.

- •

The information system on HWF has seen a notable improvement, which has facilitated setting a reasonable background for HWF mobility. We have focused our analyses on four categories of health professionals subject to available information. Nevertheless, even for these four broad categories, we have identified some drawbacks: gaps of information, limited comparability regarding professional categories, differences among sources. Deepening in the harmonisation of the definition of health professions would be beneficial, especially in the case of nurses, for more quality and detailed analyses.

- •

EU Member States are immersed in a wave of health reforms that are being financed with Recovery and Resilience Facility European Funds. Promoting health workforce planning and forecasting would emerge as a necessary action, including improving harmonised information.

- •

Additionally, harnessing the available information is paramount; and drawing in a systematic way the challenges identified in the ES reports may provide some clues to give answers to policymaking concerning health professionals’ mobility.

The European Union (EU) faces internal migrations and health authorities need to strike a balance between health policy objectives and internal market objectives, which includes abiding by the free movement of health professionals.

The purpose of this paper is to provide a general overview of the European Union (EU) health workforce (HWF) mobility. Despite the Brexit, we include the countries of the European Union-28 (EU-28) because we analyse data from years previous to it. The list of countries is shown in online Appendix B.

We approach the work under the perspective of the internal market, “an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital is ensured”. It is the framework where the Community law set “the right to pursue a profession, in a self-employed or employed capacity, in a Member State other than the one in which they have obtained their professional qualifications”. Specifically, we rely on the Directive on recognition of professional qualifications1 that governs the mobility of regulated professions in the EU, where health professions are included.

Despite the internal market perspective, we do not lose sight of the core issue for the EU and Member States’ health policy: ensuring access to health care under the conditions established by national laws and practices. As well as without losing sight that EU and Member States’ health policy cannot be carried out behind the backs of the Union's economic governance agenda. Thus, for depicting the mobility of health professionals in the EU we connect it to the challenges identified in the European Semester (ES) concerning the supply of HWF.2

This article is organised as follows: next, we briefly describe our method. Then we focus on the results. We end the analysis with some conclusions including key points. Two online Appendixes and references close the paper.

MethodTo outline the HWF mobility in the EU, we use a descriptive research method based on the analysis of secondary data, both quantitative and qualitative, from international administrative and statistical databases and from EU reports concerning the ES.

Quantitative approachWe approach the HWF mobility in the EU measuring the flows of health professionals between EU countries. We calculate a proxy variable based on the “number of positive decisions taken on recognition of professional qualifications for the purpose of permanent establishment within the EU Member States, (EEA) countries and Switzerland”. For each country, we obtain the net balance ratio (NBR): the ratio of the difference between inflows and outflows of HWF to the total number of health professionals. Concerning the flows, the source of information is the Regulated Professions Database (RPD).3 Concerning the number, the source of information is manifold. The main one is the statistical office of the European Union (Eurostat), that we have complemented with databases provided by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Please refer to online Appendix A for further detail regarding the indicators used and its sources. We notice that, handling the quantitative information in the mentioned international databases, we have verified several weaknesses (gaps of information, limited comparability regarding professional categories, differences among sources…). It goes beyond the scope of this work to address these issues. Nonetheless, from the perspective of EU and national policymaking, improving the international information systems on HWF is a needed first step to support planning and forecasting.

Qualitative approachFor characterising the mobility of health professionals in the EU, we connect it to the challenges identified in the ES concerning the supply of HWF.

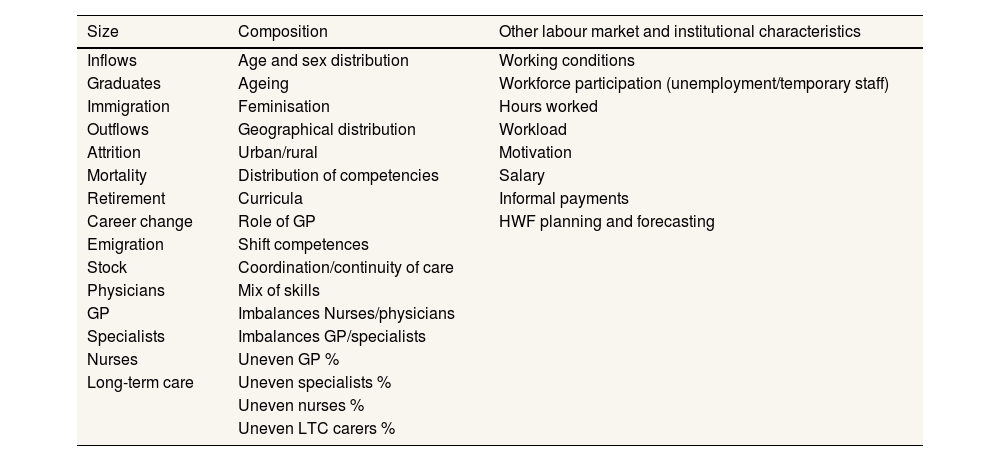

The supply of HWF depends on health care workers’ labour supply decisions that end up shaping the size and composition of the stock of health professionals. We have created a stylised framework that includes the main drivers of HWF supply. Concerning the size, we borrow from the OECD's approach4 and use the classic stock/flow model. As for the composition, we have selected some relevant characteristics linked to the supply of HWF, namely: age and sex distribution, geographic distribution, competences distribution, a mix of skills and workforce participation and hours worked. Additionally, we include some institutional characteristics.

In Table 1 we present that framework, which is “challenge-oriented”, meaning that, based on theoretical models, we have included those drivers of HWF supply for which challenges have been flagged in the context of the ES.

Drivers of health workforce supply: a “challenge oriented” framework.

| Size | Composition | Other labour market and institutional characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Inflows | Age and sex distribution | Working conditions |

| Graduates | Ageing | Workforce participation (unemployment/temporary staff) |

| Immigration | Feminisation | Hours worked |

| Outflows | Geographical distribution | Workload |

| Attrition | Urban/rural | Motivation |

| Mortality | Distribution of competencies | Salary |

| Retirement | Curricula | Informal payments |

| Career change | Role of GP | HWF planning and forecasting |

| Emigration | Shift competences | |

| Stock | Coordination/continuity of care | |

| Physicians | Mix of skills | |

| GP | Imbalances Nurses/physicians | |

| Specialists | Imbalances GP/specialists | |

| Nurses | Uneven GP % | |

| Long-term care | Uneven specialists % | |

| Uneven nurses % | ||

| Uneven LTC carers % |

GP: general practitioners; LTC: long-term care.

To gauge the extent to which these challenges could be considered a priority, we have measured its “intensity” by the number of countries where the component has been flagged during the period 2017-2023, where the accounting unit is the country and the year. To this end, we have created a textual database, including for each year and each country the description of the challenges flagged. The sources of information are the European Semester Country Reports 2023, complemented with the reports on the State of Health in the EU (2017, 2019 and 2021), that feed into the ES process and that provide more extensive details for the health sector (hereinafter, the reports). Please refer to online Appendix A for further detail regarding this indicator and its sources. We also complete with an overview of the ES Country Specific Recommendations (CSR).

ResultsQuantitative approach: flows of health professionals in the EUIn online Appendix B, Figures B1-B5, we show the result of our calculations for the NBR of HWF in the EU. We present them ordered, displaying in top positions those countries that are the top recipients of HFW.

The countries with a positive NBR are recipients of health professionals. For a given country, the nature of the ratio depends on the health profession. However, a set of countries are systematically recipients of HWF: AT, DE, IE, LU, NL and SE; BE, MT and UK are almost systematically recipients except that BE is an issuer country for nurses, MT for doctors and the UK for pharmacists. We highlight that, in the case of DE, though positive, the NBR is very close to 0 for all professions (please notice that an administrative positive decision granting the recognition for the purpose of permanent establishment to practise in the host country on a permanent basis might not always imply an effective migration). On the other side, BG, EL, ES, FI, HR, HU, LT, LV, PL, PT and RO are systematically issuer of health professionals; DK, EE, FR, IT, SI and SK are systematically issuer countries for all health professionals except pharmacists and CZ except for dentists. As for the rest (CY), we cannot identify a global pattern. However, the figures for CY show high positive values for doctors and dentists and high negative ones for nurses; where “high” means out of the upper or lower limit of the interval of one standard deviation around the mean of the distribution. According to that, the data point out that the countries with a “recipient profile” are LU, BE, CY, IE, AT, MT and SE. On the other hand, those with an “issuer profile” are RO, SK, ES, LT, LV, PT, BG, CY, EL, FI, HR, HU, IT, and SI. Please refer to online Appendix B, Table B5.

We also show the density of health professionals in online Appendix B, Tables B1-B4, derived from the number of health professionals used for calculating the NBR, which helps to set the background for HWF mobility in the EU. The data show a significant variability between EU countries, especially for nurses and dentists (the coefficient of variation exceeds 20%). Between 2010 and 2022, it registered a raising trend for all professions in the EU (online Fig. B5).

Qualitative approach: challenges related to HWF supply drivers in the EUIn online Appendix B, Tables B6 and B7, we show the results of measuring the intensity of the challenges related to HWF supply drivers as flagged by the reports. Consideration is equally focused on issues related to the size of the HWF and its composition with around 40% of intensity each one. For other labour market and institutional characteristics, the intensity drops to less than 20%.

Regarding mobility, immigration and emigration have been flagged as a challenge 15.37% of the times. The EU countries with higher intensity for the emigration challenge are RO, BG, HR, MT, PL, SK, EL, HU, IE, LT, LV, PT, CZ, EE, ES, IT and SI. On the other hand, the EU countries that have been flagged with an immigration “challenge” are LU, MT, DE, IE, UK, HU and SE. Please refer to online Appendix B, Table B7.

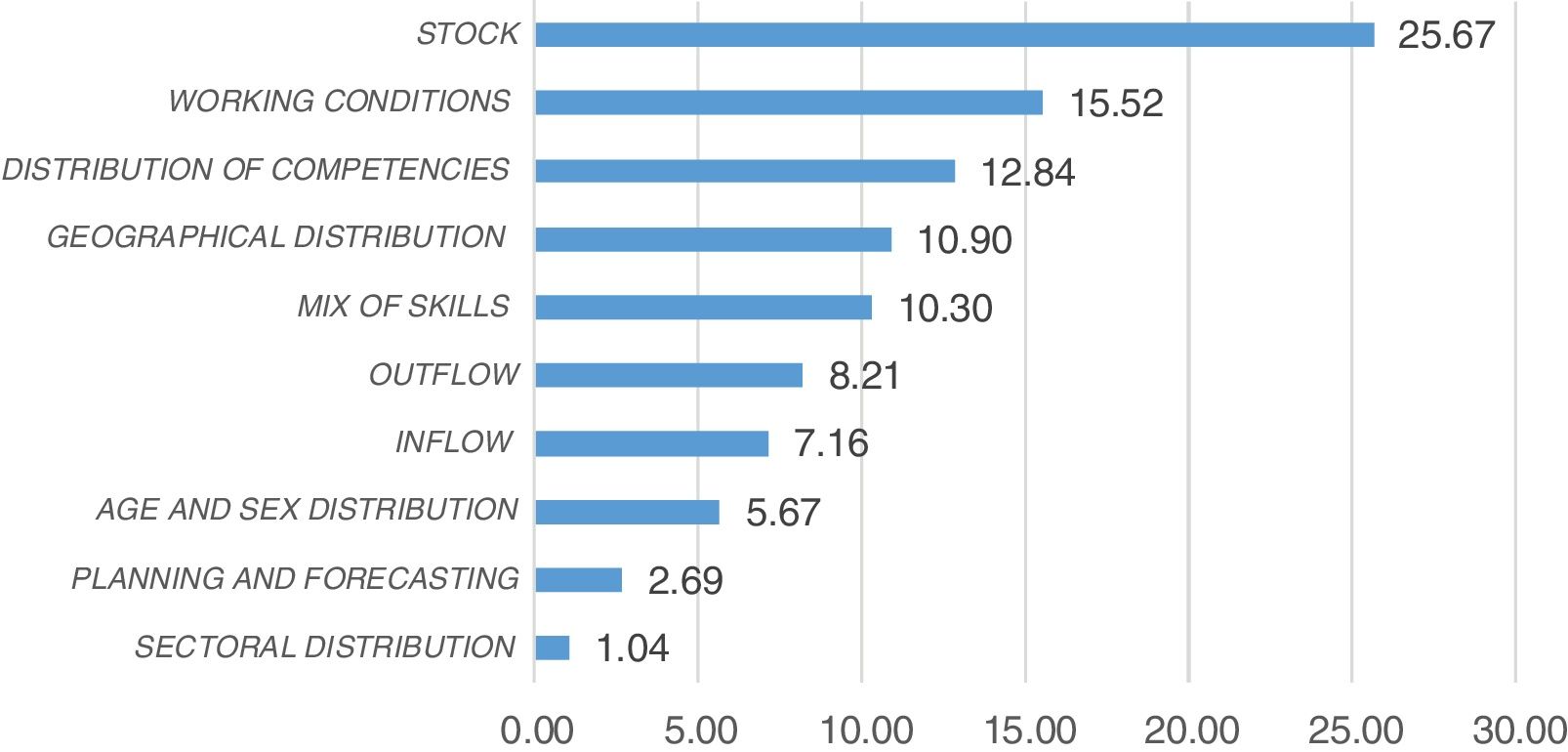

Mobility is used as a solution to shortages. We record shortages as stocks challenges, be it overall or for specific professions. They retain most of the concern about HWF size. Indeed, the reports have flagged issues of scarcity 25.67% of the times: out of 670 mentions to HWF challenges in the reports, 172 were to highlight shortages of the HWF (online Appendix B, Table B6 and Fig. 1).

Challenges related to HWF supply drivers: intensity. (Source: author's own work based on online Appendix B, Table B6.).

Typically, a serious challenge would receive a CSR to address the issue. Thus, it is helpful to draw on CSR to see the extent to which they are priority challenges. In 2020, 21 EU Member States received a CSR to address HWF issues, and most of them (17 times) were specifically on HWF shortages.

Shortages have revealed as a relevant threat during the COVID-19 pandemic. Indeed, as reported in the State of Health in the EU: Companion Report 2021, “The COVID-19 pandemic put shortages of healthcare into the spotlight, but this is by no means a new challenge to healthcare systems in Europe (…) In the 2021 edition of the State of Health in the EU's Country Health Profiles, HWF shortages are reported as a key health system challenge in 15 countries”. The mentioned report states that the demand and complexity of care provided in Europe has grown at a comparatively faster pace than the density of health workers due to population ageing and the growing burden of chronic diseases.

The reports have flagged issues of scarcity mainly for physicians and nurses. They documented a variety of reasons for that situation. For some Member States, the issue was a numerous clauses set at low level in the past that has been necessary to ease. In other cases, the country lacked a health education system and needed to set it to prevent depending heavily on foreign-national professionals. Emigration is a concern in many countries, which is also compounded by an ageing HWF, a notable part of which is about to retire within the next 10 years. The reports do not point to career changes in any country (which might be because of lack of data on this issue). On the contrary, working conditions have been flagged as a concern 15.52% of the times, the second component most signalled following scarcity of health workers. Low salary and increasing overburden of workload (which seem to be more extended in rural and deprived areas) are the most frequently mentioned components when working conditions are pointed out as an issue associated to emigration or to the decision of not choosing a health career. Although during the pandemic the use of part-time or temporary contracts have been recourse for swiftly increasing human resources, in some cases, like in Spain, there has been a shift towards temporary contract, which results in a large turnover. In a few countries, the reports point out to informal payments (12.30% of the mentions within working conditions). We have accounted for these mentions within the working conditions on the ground that this component has a detrimental effect on motivation.

Moving on to the supply factors in the composition side of the framework, what the reports show is the presence in many countries of notable imbalances in the geographic distribution of human resources, which are frequently compounded with an uneven concentration in urban areas. Typically, specialists tend to concentrate in urban areas. However, shortages of GP in rural areas are also importantly reported. In many cases the solution to the challenges requires innovation with the distribution of competencies to give a response to current needs. This starts in some cases with the design of new curricula. Changing the skills mix will also be needed, e.g. to take into account the increasing presence that is required of long-term care professionals and new health professions.

ConclusionsThe mobility of HWF has been identified as a challenge for some EU countries in the analysed period with a non-negligible intensity. Both as an issue for strong reliance on recruiting abroad (inflows) and as a threat for shortages due to emigration of professionals. The list of countries flagged with higher intensity regarding an emigration challenge is coherent with those identified with an “issuer profile” based on the database on professional qualifications. Likewise, the list of countries flagged with higher intensity regarding an immigration challenge is coherent with those identified with a “recipient profile”. There is a high coincidence on the countries flagged with an “issuer profile” under both approaches: RO, SK, ES, LT, LV, PT, BG, EL, HR, HU, IT, and SI (an 86% of the countries signalled under the quantitate approach are also under the qualitative one). On its side, LU, IE, MT, and SE could be flagged with a “recipient profile” (respectively 57%).

Mobility is used as a solution to shortages. It seems that the pandemic aggravated pre-existing shortages thus bringing to the forefront the need to strike a balance between health objectives and internal market objectives. The Romanian case being paradigmatic: Romania is systematically one of the countries most affected by internal outflows of health professionals. At the same time, it ranks high in the EU for unmet medical needs.5 By contrast, Luxembourg is the largest net recipient of health workers for all the analysed categories ranking in a very low position for unmet needs.

There are signals that the Union will need to address HWF shortages in the near future. They existed before the pandemic, which only exacerbated them. Although the evolution of the density of health workers is positive at the EU level, it seems that it has not been enough to offset the pressure on the demand side.

On the other hand, mobility as a solution to shortages is a threat to the planning and delivery of services, thus planning and forecasting appears as a relevant policy tool at national and EU level to strike the needed balance between health policy and internal market objectives. EU Member States are immersed in a wave of health reforms that are being financed with European Funds from the Recovery and Resilience Facility. Promoting health workforce planning and forecasting would emerge as a necessary action, including improving harmonised information. Furthermore, drawing in a systematic way the challenges identified in the European Semester reports may provide some clues to gives answers to policymaking concerning health professionals’ mobility.

Availability of databases and material for replicationQuantitative information:

- •

Regulated Professions Database: https://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/regprof/statistics

- •

Eurostat Database: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- •

WHO Database: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.HWFGRP?lang=en

- •

OECD Database: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?ThemeTreeId=9

Qualitative information:

- •

European Semester Country Reports 2023: https://economy-finance.ec.europa.eu/publications/2023-european-semester-country-reports_en

- •

European Semester Country Specific Recommendations: https://ec.europa.eu/economy_finance/country-specific-recommendations-database/

- •

State of Health in the EU (2017, 2019 and 2021): https://health.ec.europa.eu/state-health-eu/country-health-profiles_en#country-health-profiles-2021

A. Blanco Moreno conceived the idea presented and developed the entire process of this study.

AcknowledgementsTo Victoria de Domingo Sanz for her collaboration. To the evaluators for their contribution to improve the drafting of this paper.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.