Provide a method for reusing National Institute of Statistics (INE) socioeconomic data and reconstructing the Spanish National Health System primary care areas (PCA) from INE census tracts.

MethodThe reconstruction of PCA boundaries entailed aligning, assigning, and integrating census tracts within the limits of the PCA using 2022 INE and 2018 Atlas VPM digital maps.

Results36,282 census tracts were assigned to 2,405 PCA. The alignment of digital maps showed a programmatic assignment of 99.7% of the census tracts within PCA; just ten census tracts must be manually assigned. The net average income per capita distribution from INE was consistent along the newly reconstructed PCA.

ConclusionsWe have proposed a reliable solution to integrate socioeconomic data from INE census statistics into PCA, enhancing data researchers’ capacities in joint analyses of socioeconomic determinants and healthcare.

Proporcionar un método para la reutilización de los datos socioeconómicos del Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE), reconstruyendo las áreas de atención primaria (AAP) del Sistema Nacional de Salud a partir de las secciones censales.

MétodoLa reconstrucción de los límites de las AAP implicó la alineación, la asignación y la integración de las secciones censales dentro de los límites de las AAP utilizando mapas digitales del INE 2022 y Atlas VPM 2018.

ResultadosSe asignaron 36.282 secciones censales a 2.405 AAP. La alineación programática asignó un 99,7% de las secciones censales; solo diez requirieron ser asignadas manualmente. La distribución de la renta media neta per cápita del INE fue coherente a lo largo de las AAP reconstruidas.

ConclusionesProponemos una solución fiable para integrar los datos socioeconómicos de las estadísticas censales del INE en las AAP, mejorando las capacidades de los investigadores con interés en el análisis de los determinantes socioeconómicos y los sistemas sanitarios.

Social and socioeconomic determinants have been associated with differences in health status,1 use of healthcare care services2 and health outcomes regardless of other factors.3 In turn, systematic differences in elective surgical procedures, safe prescriptions, quality of diabetes care, and the cost of services have been shown to vary broadly across social and economic levels.4

In the Spanish National Health System (SNS) design, primary care plays a fundamental role in achieving effective universal health coverage5 and is deemed a major driver of income redistribution. However, the study of the interplay between socioeconomic determinants and primary care has not been systematically addressed; thus, larger-scale studies, including the entire population living in primary care demarcations, and a methodology that allows consistent updates of their data over time are needed.6

Despite these initiatives, the study of the influence of non-health determinants on health services performance needs a more systematic approach, performed in larger populations —ideally, the entire population living in a healthcare demarcation— and updated over time. The SNS's wealth of data7 lacks the information required to address this need.8 Noticeably, the National Institute of Statistics (INE) systematically collects many socio-economic data (e.g., Population and Housing Census indicators9 and the Household Income Distribution Atlas10) that could be reused if transformed into the relevant healthcare analysis units.

This paper aims to provide a method for reusing INE socioeconomic data at scale. We reconstruct the SNS primary care areas (PCA) from INE census tracts and illustrate how an INE census-level indicator is allocated to the reconstructed PCA map. Finally, we implement a digital map with which data researchers can reproduce the analyses with other INE indicators.

MethodAllocating socioeconomic census data into PCA requires creating new PCA out of the geographical vectors of the census tracts. This process, well described in geo-statistics,11 comprises seven steps:

Map alignment: the digital map of the census tract (i.e., the unit of origin of data) and the digital map of PCA (i.e., the destination unit) were aligned. For this purpose, we used the census tracts’ digital map from 2022 produced by INE12 and the 2018 digital map for the PCA implemented by Atlas VPM (see Table S1 in Supplementary material).13 This stage comprised the alignment of 36,282 census tracts and 2,405 PCA. Instrumentally, alignment required transforming the geographic coordinates to a common standard using the geodetic coordinate reference system for Europe (EPSG:4248 - ETRS89). As Atlas VPM does not cover the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla, no digital map was available to implement this phase.

Assignment of census tracts to PCA: assignment of tracts to PCA was carried out using point estimates (centroid) to allocate each census tract within a single PCA.

Nesting evaluation by double-checking overlapping areas between the two maps: given the geographic misalignment of the two maps, the assignment in step 2 required further instrumentation. Analysing the areas of both maps, we assessed the actual census area matching the corresponding PCA, assuming a 5% loss, meaning we accepted the assignment when at least 95% of the area was common to both maps.

Re-assignment of poorly nested areas: the remaining census tracts whose area did not intersect at least 95% of the area were taken for additional assignment. Thus, we generated one thousand points following a random distribution (a large enough number of points to scope the surface of the area polygon) within the boundaries of the census tracts. The census tract was assigned to the PCA where most points intersected with (mode criterion).

Reconstruction of the PCA map: once the assignment was finalised, the boundaries of the census tracts were merged into a single area border, which are the boundaries of the new PCA.

Allocating socioeconomic values to the new PCA: we allocated the average net income per capita values to the new PCA for illustration purposes.

Internal validation of the estimates: we compared the distribution of net income per capita values in the census tracts with those in the reconstructed PCA. A difference between both distributions would elicit inadequate assignment.

All analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (v4.3.2; R Core Team 2021)14 and are accessible under an open-source licence at the GitHub repository for the Data Science for Health Services and Policy research group.15

ResultsIn this study, 36,282 census tracts were assigned to 2,405 PCA. The maps’ alignment showed a programmatic assignment of 99.7% of the tracts within PCA; just ten tracts required manual assignment. 93.6% of the tracts were assigned to a PCA, assuming the 95% threshold. Among the remaining 2,312 tracts not complying with that threshold, 171 (7.4%) required reassignment to a different PCA.

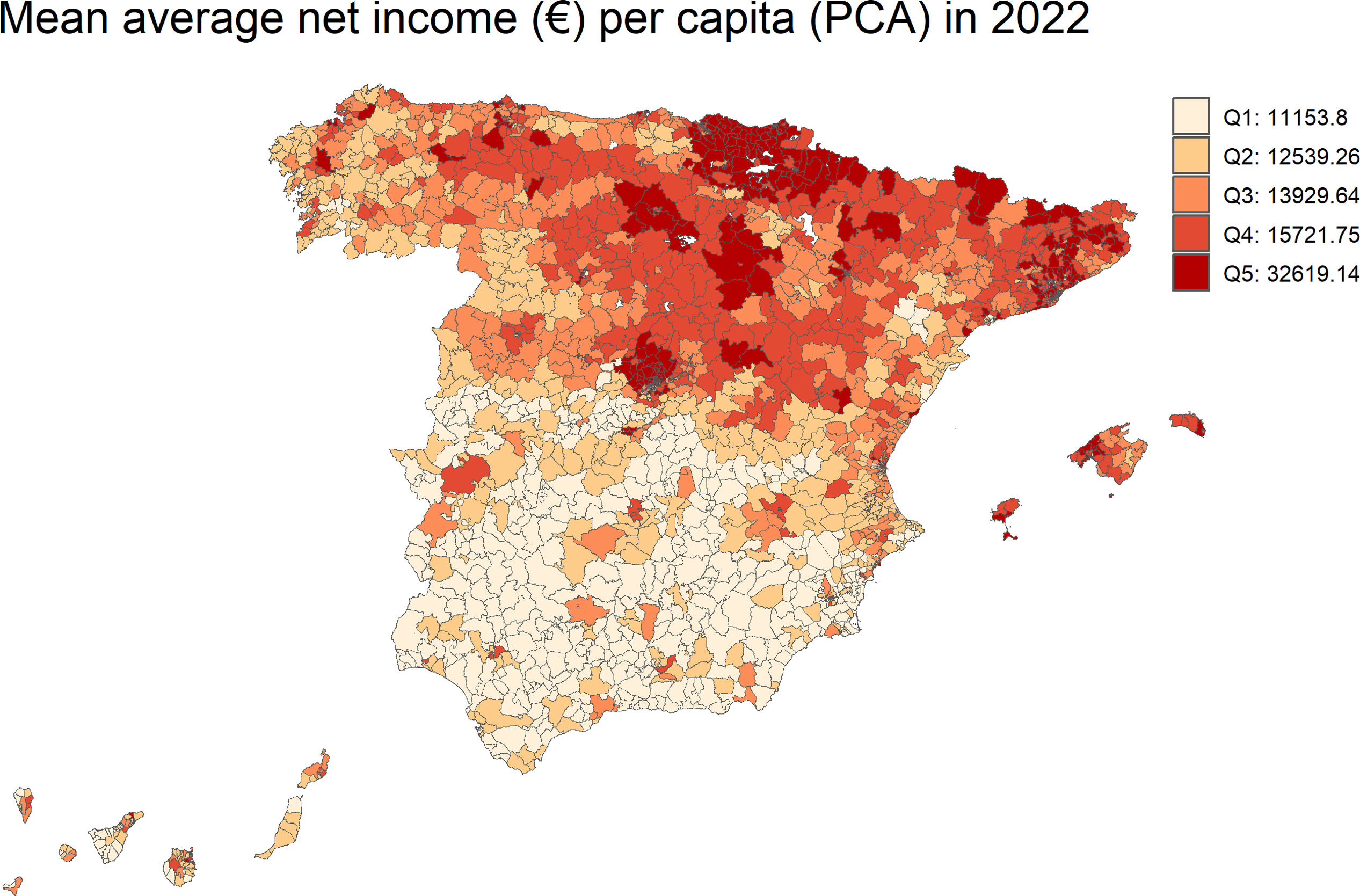

As a matter of illustration, the mean average net income per capita was plotted using the reconstructed new PCA (Fig. 1).

Distribution (quintiles) of the mean average net income per capita by primary care area (PCA) for the National Health System in Spain. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from: https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024.

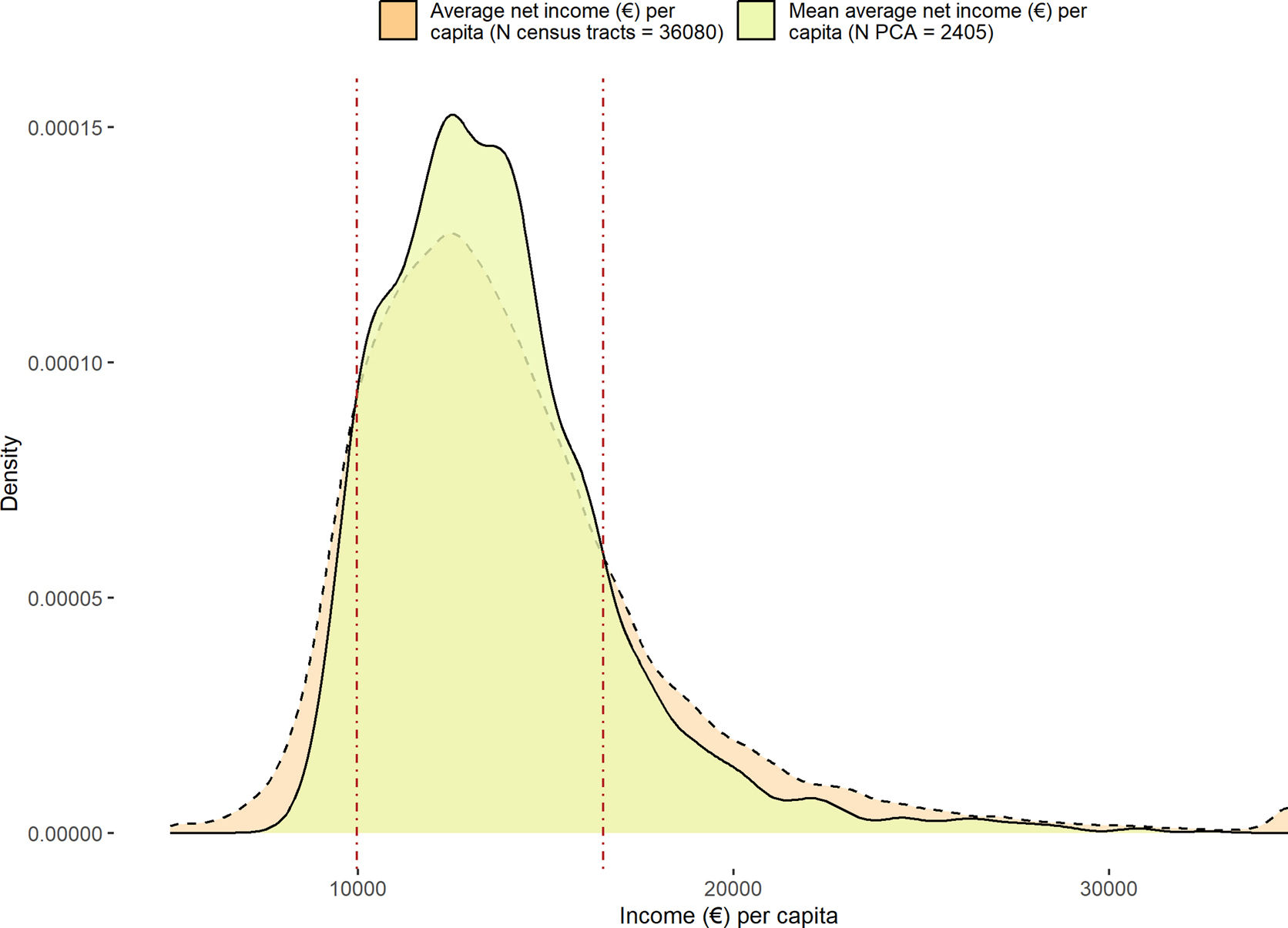

In figure 2, we exhibit the density distribution of the average net income per capita for each census tract compared with the mean average net income per capita for each primary care area using the new PCA. The figure shows substantial overlap between the two areas under the curve, with a reduction in the variation attributed to clustering census tract values within each PCA.

A comparison of the density distribution of average net income per capita per census tract versus the mean average net income per capita per primary care area (PCA). The figure shows no major differences between both distributions. The dashed vertical red lines show the cut-off points of the curves (left: € 9,966.7; right: € 16,528.4). Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024.

The developments in this paper have been designed to be easily adaptable to changes in the PCA maps’ boundaries and have been made FAIR to be reproducible in small area analysis requiring the allocation of census-level data to PCA. The digital map reconstructed PCA and the CSV file, including the census tract information and corresponding PCA, can be reused from GitHub with a CC-BY 4.0 International open-source license.15

DiscussionIn this paper, we describe a solution to yield a PCA map out of the assignment, nesting and clustering census tracts, which can be easily updated upon changes in any census tracts or PCA over time with minimal intervention (only 10 out of 36,282 census tracts had to be manually assigned). This enables the integration of socioeconomic information released by the INE at the PCA level.

As referred to in figure 2, there is no perfect overlap between the census tract density curve and the reconstructed PCA density curve, thus reducing the variation in the endpoint of interest. In this illustration, the areas not overlapping account for less than a third of the total census areas; nonetheless, the actual impact on the estimation is reasonably low; thus, a potential overestimation of median € 329 in net annual income in those PCA at the left tail, and a potential underestimation of median € 588 in those areas at the right tail. This difference is likely due to merging smaller areas (census tracts) into larger units to reconstruct the PCA.

In addition, it may be argued that the reconstruction of the PCA was merely based on geographic criterion, thus not considering the potential differences in the population distributions when using census tracts or PCA. An analysis of the population density distributions in the original PCA and the new PCA shows a complete overlap of the areas under the curve (see Fig. S1 in Supplementary material) and an extremely high correlation (Pearson correlation=0.95).

The new map resulting from the integration of socioeconomic information allows data researchers to model the ecological influence of socioeconomic determinants on health system performance for the whole population exposed to the geographic areas delineating our health system, specifically PCA. The increased analytical capacity of connecting social and demographic data at the basic geographic level with information on health and health service utilisation allows for evaluating policies to reduce social inequalities in health.15

In this paper, we have provided a solution to reproduce the same analysis with other INE indicators. However, testing alternative implementations or giving access to an application programming interface developed as R or Python libraries, providing functions to access and plot a PCA integrated map or to complete the nesting evaluation workflow over a new census tract map, could enable seamless updates once new regional census data and PCA maps are updated and made public, thus enhancing research capacities.

ConclusionsWe have proposed a reliable solution to integrate socioeconomic data from INE census statistics into PCA. Following this solution, Atlas VPM has made the first SNS map at PCA publicly available, allowing the integration of health, healthcare, socioeconomic, and demographic information designed to be reproducible and easy to update. This resource may pave the way for at-scale inclusion of the socioeconomic perspective in health services and policy research at the primary care level.

Availability of databases and material for replicationAll databases and material (scripts) for replication are available under a Creative Commons 4.0 International Attibution (CC-BY) licence at GitHub (https://github.com/cienciadedatosysalud/AtlasVPM-socioeconomic).

The National Statistics collects and publishes socioeconomic data at the census tract level. However, aligning this data with the geographic information relevant to the health system, particularly primary care areas, is challenging.

What does this study add to the literature?This study reconstructs the geographic information of primary care areas, enabling the allocation of socioeconomic details at that level.

What are the implications of the results?The new map resulting from the integration of socioeconomic information allows health services and policy researchers to model the ecological influence of socioeconomic determinants on health outputs and outcomes at a meaningful level of analysis.

Vicente Ortún.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author, on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsF. Estupiñán-Romero and S. Royo-Sierra conceptualised and researched the methodology. S. Royo-Sierra and J. González-Galindo completed the data management, transformation, and analysis. All authors participated in writing the original draft. M. Ridao-López and E. Bernal-Delgado reviewed and edited the final manuscript, which all authors approved.

AcknowledgementsWe would like to express our sincere gratitude to the Atlas VPM consortium for their invaluable contributions to this research.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

![Distribution (quintiles) of the mean average net income per capita by primary care area (PCA) for the National Health System in Spain. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from: https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024. Distribution (quintiles) of the mean average net income per capita by primary care area (PCA) for the National Health System in Spain. Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from: https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/02139111/unassign/S0213911125000184/v1_202503170414/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=68ByKAw1uJ1JN/aQC3VY4w==)

![A comparison of the density distribution of average net income per capita per census tract versus the mean average net income per capita per primary care area (PCA). The figure shows no major differences between both distributions. The dashed vertical red lines show the cut-off points of the curves (left: € 9,966.7; right: € 16,528.4). Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024. A comparison of the density distribution of average net income per capita per census tract versus the mean average net income per capita per primary care area (PCA). The figure shows no major differences between both distributions. The dashed vertical red lines show the cut-off points of the curves (left: € 9,966.7; right: € 16,528.4). Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Spanish Statistical Office (2024). Household Income Distribution Atlas. Retrieved from https://www.ine.es/en/experimental/atlas/experimental_atlas_en.htm. [Accessed October 29, 2024]. Latest data release: October 29, 2024.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/02139111/unassign/S0213911125000184/v1_202503170414/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr2.jpeg?xkr=68ByKAw1uJ1JN/aQC3VY4w==)