Social prescription targets people with social isolation or unwanted loneliness and offers them community activities to improve their emotional well-being. Disabled homebound people cannot access social-health community assets. Neighborhood volunteers may accompany them at home or walk them outdoors. Community emotional well-being referent may enhance these interactions, conducting emotional counseling and management groups for volunteers.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the effectiveness of community intervention of accompaniment and emotional management with volunteers on unwanted loneliness in people with social isolation, their emotional well-being, and quality of life.

MethodA community non-randomized trial on isolation with a qualitative nested study on unwanted loneliness. Detection by a driving group, made up of neighborhood organizations and the community health team, in an opportunistic way. Implementation of the multi-level volunteer-isolated people intervention. In cases where we detect architectural barriers, we will provide technical aids (portable stairlifts).

La prescripción social se dirige a personas con aislamiento social o soledad no deseada y les ofrece actividades comunitarias para mejorar su bienestar emocional. Las personas aisladas discapacitadas no pueden acceder a los activos socioculturales de la comunidad. Los voluntarios del vecindario pueden acompañarlos en casa o a socializar al aire libre. La referente de bienestar emocional comunitario puede mejorar estas interacciones, realizando grupos de asesoramiento y gestión emocional con voluntarios.

ObjetivoEvaluar la efectividad de una intervención comunitaria de acompañamiento y gestión emocional con voluntarios sobre la soledad no deseada en personas con aislamiento social, su bienestar emocional y su calidad de vida.

MétodoEnsayo comunitario no aleatorizado sobre el aislamiento con un estudio anidado cualitativo sobre la soledad no deseada. Detección por parte del grupo motor, conformado por organizaciones vecinales y el equipo de salud comunitaria, de manera oportunista. Implementación de la intervención multinivel voluntario-personas aisladas. En los casos en que se detecten barreras arquitectónicas, se proporcionarán ayudas técnicas (salvaescaleras portátiles).

Determinants of mental health include community social support.1 Equity is achieved by reducing health inequalities, dealing with social problems, and promoting social cohesion.2 Social prescription aims to improve the health and well-being of people with social or emotional problems by promoting access to community resources.3 Social prescription empowers marginalized groups and vulnerable individuals, creating connected, resilient, and cohesive communities. It involves activities provided by community sector organizations and volunteering.4 Disabled homebound people cannot easily access social prescription. Models of reinforced primary care and compassionate communities, combining volunteer facilitators, social prescription, and personalized models of care focused on people and relationships, can proactively break down community barriers.5

Social isolation refers to objective features, whereas loneliness is a subjective feeling resulting from the perceived discrepancy between desired and achieved levels of social relations6 that provokes negative emotions and invalidity facing social and nature forces.7 It is a multidimensional construct that includes emotional, relational, and collective loneliness.8 It serves evolutionarily adaptive functions9 but can impair executive functioning, sleep, and mental and physical well-being,10 contributing to higher morbidity and mortality rates in lonely older adults11 and, when chronic, promoting cardiovascular disease, stroke,12 or dementia.13

Interventions14 on isolation and loneliness may be self-delivered, changing individuals’ attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors; interpersonal delivered, focusing on building meaningful personal relationships; community-based, increasing social interaction opportunities, connecting to community group activities or peer support groups; social-level delivered, focused on policies and laws addressing social risk factors, like discrimination and stigma, socioeconomic inequality, or changing social norms impeding social connection; and multi-component/complex.15

Evaluating effectiveness of interventions to reduce loneliness may require a deeper theoretical understanding of the contextual and social factors.16,17 There are quite studies of accompaniment in the elderly18–20 but a recent review21 recommends more research focused on holistic active-empowering development processes of interventions, and participatory activities including people without this problem, as fits the aims of a community collaborative primary care policies.22

Volunteering can help mental health and survival.23,24 It includes the general interest activities motivated by altruism and the desire for social transformation conducted within an associative activity or a non-profit organization.25 Health programs must carefully select volunteers, emphasizing training and accompaniment.26 It is a tool for social inclusion, contributes to overcoming stigmatizations, and requires emotional stability.27

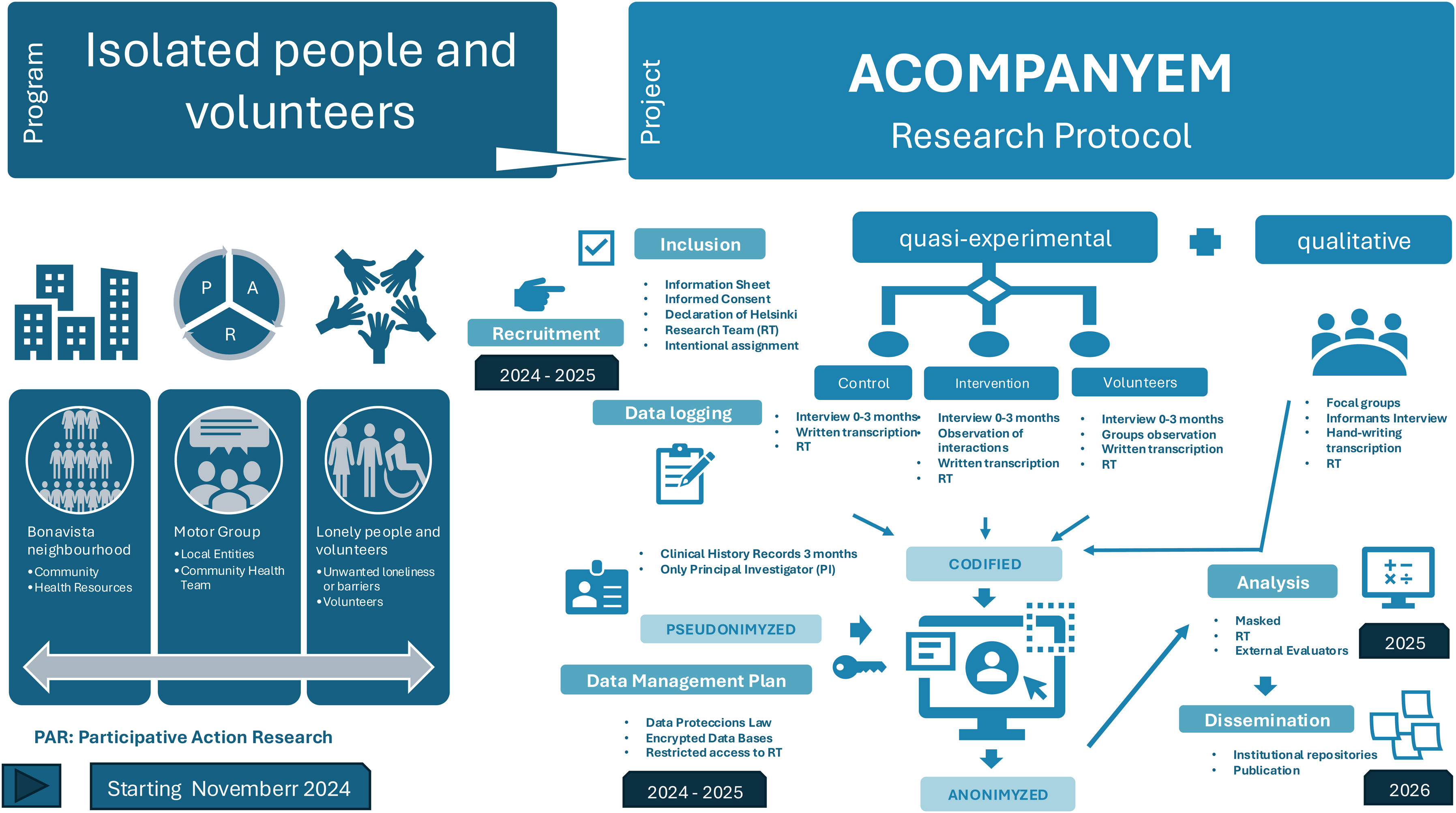

Our participatory action research program ACOMPANYEM (see online Appendix for a presentation with more details) looks to equitably integrate the most isolated people into their network of community assets and social prescription, inviting neighborhood entities to form a motor group to jointly address emerging situations. We propose a complex, multilevel intervention at the community level with the participation of volunteers, to study the unwanted loneliness phenomenon.

MethodThe general objectives are to evaluate an intervention on the unwanted loneliness of people with social isolation, their emotional well-being and quality of life; on the volunteers and the community, and on social and health services.

The specific objectives are to analyze the socio-demographic characteristics of isolated people and volunteers, specifically in older people; the physical and psychological impediments affecting individuals and their relational expectations; isolation/social well-being in vulnerable groups or at risk of social exclusion (people abused, with severe mental health disorders, physical or intellectual disabilities, addictions, homeless, migrants or with economic precariousness); the reduction of social/personal isolation and whether there is integration into the community; the effects of the intervention in the community; and the satisfaction with the technical aids incorporated to come outdoors.

The hypothesis is that an intervention by volunteers from the neighborhood supported by the community and the health team can produce beneficial effects on the unwanted loneliness of patients isolated at home or with socialization problems, as well as on the emotional well-being of the volunteers who accompany them. The operational hypothesis is that a multilevel community intervention could decrease social isolation in our study population in 50% of cases.

It is a mixed design, community non-randomized trial, with intervention group (volunteers) and 50% allocation control parallel group (usual care) to prove superiority of the intervention over habitual care, plus a nested qualitative study framed in a participatory action research program with constructivist analysis method.

The scope of the study is a peripheral urban neighborhood of 15,280 people, where one in four people aged over 75 lives alone (37.4% women).

The intervention consists of bringing together two population groups in the community with complementary needs:

- –

People of all sexes over 16 years of age, with inclusion criteria: disabled physical or mental homebound persons; unwanted loneliness, with difficulty in accessing social prescription program; and <8 on the Oslo Social Support Scale or <20 on the Lubben Social Network Scale in people aged over 65. Plus, exclusion criteria of impossibility of communication or end-of-life situations.

- –

Neighborhood volunteers, especially people interested in improving their emotional well-being.

A personalized relational dynamic of help will be set up in each case (one-to-one interaction, relational level), consisting of listening at home or going with the person outdoors to bring them closer to the different proposals for social activities. Participants will also receive support from the community team, to provide a personalized response to the needs detected by the volunteers (socio-health interaction, individualized level). Volunteers will have a psychoeducational space led by the community emotional referent, who will guide them in emotional management, train them in the accompaniment of physically and/or emotionally fragile patients and reinforce pro-social activities. Promoting the emotional well-being of the volunteers themselves (group level interaction) will also be worked on. Motor group and volunteers will jointly coordinate and propose resources (community-level interactions). We will display technical aids (portable stairlifts), where we detect architectural barriers, and study their impact.

In-waiting list for intervention in future rounds and habitual care for control groups.

The primary outcomes are shown in Table 1.

Primary outcomes.

| Outcome measure | Instrument | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Social support/isolation | Social Support Scale (OSLO 3)28 | Studies the relationship between support and psychological suffering |

| Social support/isolation for aged >65 | Lubben Social Network Scale29 | Examines the size of an elderly person's social network, the proximity and frequency of contacts from their social network |

| Emotional well-being | Emotional Well-being Scale (7 items) SWEMWBS30 | Explores how the person has felt in the last two weeks |

| Health-related quality of life | EuroQol 5D-5L31 | The value of severity of symptoms in five health dimensions |

| Loneliness | Semi-structured interviewStructured observation Focus groups | Qualitative techniques plusTwo binary-answer questions: Do you feel lonely? (yes/no), Do you wish to be accompanied? (yes/no); each followed by visual analogic scale to measure extent |

A sample size is obtained using a Granmo calculator of 28 subjects to detect a 50% decrease in social isolation, accepting a 0.05 alpha risk and a beta risk of 0.1, in a one-sided contrast, accepting a 30% follow-up loss rate for matched data before and after exposure to the intervention. For the same proportion, risk and potency conditions for independent data with a control group, 14 participants are required in each group. The sample for qualitative evaluations will follow criteria for saturation.

Recruitment by the professionals of the primary care health center and the motor group. There will be informative leaflets to reach the population of the neighborhood (see online Appendix). Volunteers will have an interview with the researchers and community emotional well-being referent to confirm that they meet the inclusion criteria.

Allocation is non-randomized. Participants will be intentionally assigned individually to either the intervention group or the control group. We will stratify the recruited subjects according to a specific characteristic to meet social equity criteria. We will try to ensure that the control group conforms to similar profiles that allow homogeneous initial data but on the waiting list to start the next round of intervention.

Quantitative data analysis will be blinded after interventions assignment. Assessors will be blinded to all data. A data management plan including anonymization will be followed (Fig. 1).

Descriptive statistical analysis by sociodemographic variables. Relationship functions for continuous and discrete quantitative variables for paired and independent data with SPSS statistical package and EXCEL spreadsheet. Qualitative analysis with categorization techniques based on the analysis of open interviews and focus groups. Clarke's situational analysis methodology32 allows for multilevel qualitative analysis by combining maps of contextual, social, and positional dimensions and can be incorporated into participatory action research designs.

Ethical considerationsThis study has obtained an independent ethical committee approval and will be conducted according to current regulations under the Declaration of Helsinki.

Gender perspective will be considered within a position of recognition of the non-equity axes that concur intersectional in a population with adverse socioeconomic indicators.

Earlier studies found, paradoxically, a worsening of loneliness in participants after interventions, due to finishing the interaction with the researchers or volunteers. To avoid this effect, we frame the study within a broader community health program that looks to increase health equity; hence, our intervention is not planned to be punctual in time, but we intend to continue and reformulate it in each cycle of participatory action research.

DiscussionUnwanted loneliness is a major health issue affecting the physical, mental, and emotional well-being of individuals but also civil society and the Health Care System. We propose a multilevel community intervention.

As a community-based study, lax criteria will be applied in the inclusion of patients and in the recruitment of volunteers and participants from the neighborhood. This allows for increased external validity but may compromise the internal validity of the study.

The schedule will depend on the pace of volunteer recruitment and constructive collaboration with the community. A motor group is engaged in the neighborhood to promote the project and coordinate the study, offering their social assets, and taking part within the research team as essential collaborators.

We aim to involve institutional sectors with administrative power to influence the social determinants of health through investment policies in those activities that are positive and inclusive for the most isolated population and generate debate in the community about isolation and social exclusion.

Editor in chargeSalvador Peiró.

Authorship contributionsAll authors have contributed substantially to the conception and design of the study, the writing of the protocol and its review with important intellectual contributions. All of them have approved the final version for publication and all the parts that make up the manuscript have been reviewed and discussed between them.

AcknowledgementsThe authors would like to thank the work of the entire community health team of the Health Care Center of Bonavista, who are also collaborating researchers in the project, of all the colleagues and professionals of the center, EAP Tarragona 1, of the medical trainees and of the Research's Support Unit, Gerència Territorial Camp de Tarragona, ICS. To the Motor Group of the neighborhood for their support in the project preparation meetings and for their involvement. To Dr. Mireia Camós who has reviewed and contributed some good ideas to the manuscript and diagram. To the entire population of the Bonavista neighborhood, whose public health is the goal that gives meaning to our community work.

Research team: Ana Reyes, Jessica Guinart, Nuria Sarrá, Benilde Domingo, Concepció Muñoz, Marta Puchades, Ángela García, Julio Ros, Irene Torres.

Motor group: Teresianes, Càrites, Centre Cívic, Respira i Viu, Joventut i Vida, AAVV Bonavista, Treballadors Socials Ajuntament, Fundació Topromi, Fundació Onada, Patronat Municipal d’Esports, Fòrum Cultural, Oficines de Farmàcia de Bonavista, Llar de Jubilats, Club Genkai, Instituts de Bonavista.

FundingThe cost of the publication of the protocol and the study comes from a prize of €3,000 awarded in an open call by the Department de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya for community projects. The future study is pending a grant from the IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina for research projects in primary care.

Conflicts of interestAll support for the present manuscript (e.g., funding, provision of study materials, medical writing, article processing charges, etc.) comes from the APiC award granted by the Department de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya for community projects. The payment will be made to our institution, ABS Tarragona-1. The authors have not received in the last 36 months any other grant or contract from other entities, nor consulting fees, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, speakers’ bureaus, manuscript writing or educational events, payment for expert testimony, private support for attending meetings and/or travel, patents planned, issued or pending, for participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board, leadership or fiduciary role in other board, society, committee or advocacy group, paid or unpaid, stock or stock options, receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services, nor other financial or non-financial interests.

RegisterEthics committee approvalIRB code: 24/095-P on May 14, 2024.