To investigate the use of healthcare services and factors associated with accessing them among Chinese immigrants living in Southern Spain.

MethodA mixed methodology was used. A cross-sectional survey was first administered to Chinese immigrants (n=133), and they were asked about their visits to the doctor, use of emergency services, and hospitalization. A phenomenological approach was then used with key informants (n=7). In the interviews, additional information, such as barriers and facilitators to improving accessibility, was explored.

ResultsIn the previous year, 51% had visited a doctor and 34% had visited an Emergency Department. The main reasons for hospitalization were pregnancy (37.5%) and surgery (25%). At least 20% of the sample reported having never visited a doctor. Language difficulties and time constraints were identified as important barriers to accessibility. Sex differences were found among the reasons for lack of time, which, in men, were related to work (odds ratio [OR]=7.7) and, in women, were related to childcare (OR=12). The majority of Chinese immigrants preferred to use Traditional Chinese Medicine as their first treatment rather than visiting a doctor.

ConclusionsA lower use of health services was found among Chinese immigrants in Spain compared to the native population. When using health services, they choose acute care settings. Communication and waiting times are highlighted as major barriers. Adapting these demands to the healthcare system may help immigrants to trust their healthcare providers, thus increasing their use of health services and improving their treatment.

Investigar el uso y los factores asociados al acceso a los servicios de salud en inmigrantes chinos residentes en el sur de España.

MétodoSe utilizó una metodología mixta. Primero se administró una encuesta transversal a inmigrantes chinos (n=133). Se les preguntó sobre sus visitas al médico y el uso de servicios de emergencia y de hospitalización. Luego se utilizó un enfoque fenomenológico con informantes clave (n=7), explorando información adicional, como barreras y facilitadores para mejorar la accesibilidad.

ResultadosEl último año, el 51% había visitado al médico y el 34% un servicio de urgencias. La hospitalización se debió principalmente a embarazo (37,5%) y cirugía (25%). El 20% informó que nunca había visitado al médico. Las dificultades de lenguaje y las limitaciones de tiempo fueron barreras importantes para la accesibilidad. Se encontraron diferencias de sexo para la falta de tiempo; en hombres se relacionaron con el trabajo (odds ratio [OR]=7,7) y en mujeres con el cuidado infantil (OR=12). La mayoría prefirió usar medicina tradicional china como primer tratamiento en lugar de visitar al médico.

ConclusionesSe encontró un menor uso de los servicios de salud entre los inmigrantes chinos en España en comparación con la población autóctona. Al utilizar los servicios de salud, eligen los cuidados agudos. La comunicación y los tiempos de espera destacan como barreras principales. Adaptar estas demandas al sistema de salud puede ayudarles a confiar en sus proveedores de atención médica, aumentando el uso de los servicios de salud y mejorando su tratamiento.

Access to health services is a determining factor for appropriate health care.1–3 Different authors agree that accessibility problems have an impact on vulnerable groups, such as low-income individuals, women, and immigrant groups.4 The causes of this impaired accessibility include cultural differences, communication and administrative problems, legal status, and even the attitudes of health workers.5 This translates into poorer outcomes, such as dissatisfaction, concern about visiting health centers, overcrowding of emergency services, and health problems.6

Studies indicate that the immigrant population has a worse perception of health than the native population.7,8 In this context, Spain is one of the top ten destination countries for immigrants, totaling 9.5% of the world's foreign population in 2016,9 making this problem a public health concern.

Despite the role that immigrants play in today's European societies, publications on immigrant health remain scarce in the scientific literature. This is due to the underrepresentation of the immigrant population in health-related studies,10 as well as the fact that surveys are not adapted to the context and language of immigrants.11

Previous studies have found that, although the immigrant population in Spain made few primary care visits and was hospitalized less often than the native population, they used the emergency services more frequently,12 which reflects a possible incompatibility of work schedules and lack of continuity of care in this population.7,13–15

Although Chinese is the fifth largest nationality of immigrants in Spain (4.46%),16 the information available on Chinese immigrants is limited. Language barriers, intense working conditions, traditional medicine use and other accessibility-related reasons are related to their exclusion in most health surveys.17 In addition, because the perception of health between the East and the West is quite different, these misconceptions may influence their understanding of health and disease and their use of health resources.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to describe the use of health services among Chinese immigrants and to identify related factors of this population when accessing the health system.

MethodThis is a mixed design study. It was approved by the Andalusian Research Ethics Committee (Internal Code: 0873-N-16).

Quantitative phase- 1)

Study design and setting

The cross-sectional study was carried out in Seville, the Southern Spain, to make a first contact with the Chinese immigrant population. Seville is the second province of Andalusia with the most Chinese immigrant population (24.6%).16 In the Spanish cities, there has been an influx of foreigners in recent years, which makes it difficult to socially assimilate immigration changes.18 Due to the difficulties in approaching these Chinese immigrants, such as language and cultural differences,19 a convenience sample and a “snowball sampling” procedure were used. All individuals signed an informed consent to participate.

Participants included were immigrants of Chinese origin living in Spain; emigrated to Seville; were between 19 and 44 years old; and were able to communicate in Mandarin Chinese, Spanish, or English. According to some authors, immigrant's age should be limited to avoid the influence of older adults on the analysis.7,20 Although in some studies the age ranges from 19-60 years,21,22 the majority of Chinese immigrants are between 20 and 55 years, due to the main reason for immigration is labor, which implies young people of active age.23,24 This coincides with the average age proposed in our work and in others with an immigrant population.25–29

- 2)

Procedure

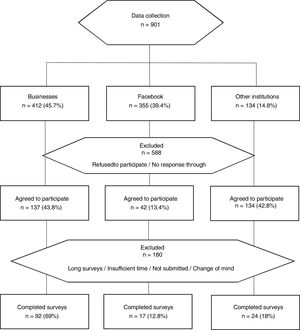

Data collection took place between September 2016 and January 2017. A total of 252 businesses (e.g. bazaars, restaurants, wholesale businesses) were visited, and 92 questionnaires were completed correctly (22.3%). In order to expand our sample, social media was used and 17 (4.5%) people completed the entire questionnaire. Finally, 134 Chinese from institutions (mostly educational institutions, Asian cultural centers, and health services) were also contacted and 24 questionnaires were completed (18%) (Fig. 1). Most participants were approached in their workplaces. Mainly, face-to-face surveys were conducted, taking 60minutes to complete its. Some participants requested to fill in the questionnaire later (due to work activity). Finally, people contacted through Facebook preferred to complete the survey online and then send them to the MR (via e-mail).

Prior to use, a content validation of the tool by a group of experts in health promotion (n=6) and a pilot with 30 participants were carried out.26 After the pilot, a new content validation was carried out by a group of Chinese native speakers (n=3) who have been living in Spain for more than 10 years. For the cross-cultural adaptation of the tool, a Spanish-Chinese translation was carried out by Chinese natives (n=3), and a Chinese-Spanish back-translation by other Chinese native (n=1) as well as by a translation company.

- 3)

Variables

The present survey was based on the National Health Survey of Spain.30 The variables were:

Demographic variables. Independent variable was sex (male and female). Other were marital status (single, married, living with partner and divorced), level of education (secondary or lower and vocational or university), employment status (employed or unemployed). Continuous variables were age and length of residence in Spain.

Accessibility to health services. Visits to the doctor, use of emergency services and hospitalization, main reasons for visit (acute health problems, check-ups, accidents and sick leaves or discharges), place of the last visit (public primary care centers, public emergency services, and private health centers), type of emergency services used (public hospital, private hospital, and public primary care center), other special health services used (radiology, dentistry, and homeopathy, naturopathy, and acupuncture), reason not to receive healthcare (long waiting time and lack of personal time). Continuous variables were days of hospitalization, and number of visits to emergency services.

- 4)

Statistical methods

Descriptive analysis was carried out using absolute and relative frequencies, as well as mean, median, and standard deviation. Inferential analysis was performed using chi-squared tests, odds ratios or Mann-Whitney tests depending on the nature of the variable (categorical, ordinal or continuous). Normality was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and, based on the result, the tests were selected as independent t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests. Analyses were performed using the SPSS statistical package (version 23.0). In addition, a p <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Qualitative phase- 1)

Design and sampling

A phenomenological approach was used with semi-structured interviews. The sampling was intentional and was carried out using saturation criteria. Relevant key informants from the Chinese community were indicated by members of the Chinese community in Seville and selected based on their relationships, roles, and knowledge regarding the Chinese immigrant population. A total of seven interviews with key informants were conducted between January and March 2017 (Table 1). We strove for a sample of participants reflecting diversity in, age, jobs, and experience living in Spain. The intention was to increase the credibility of our findings and their transferability to other Andalusia areas. Exceptionally, the inclusion of second-generation people (n=2), and Spanish one (n=2) with strong ties with the Chinese community was accepted. A field diary was also kept through the continuous and cumulative recording of everything that happened during the research and the informal conversations that were held with Chinese immigrants while filling out the survey in the quantitative phase.

- 2)

Instruments

Profile of key informants.

| Identification | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| KI-1 | Male; 38 years old; Spanish. University professor of Chinese. Expert in Chinese language and culture, traveling extensively to China. Has strong ties with the Chinese community as well as with his home country, Spain. |

| KI-2 | Male; 41 years old; born in China. Company manager; 19 years in Spain. Director of a Chinese language school. Collaborates with the health systems to adapt their services to the Chinese community. |

| KI-3 | Female; 26 years old; born in China. Doctor; 6 years in Spain. Works in a public hospital and knows the most common diseases that affect the Chinese community and how to manage and treat this community properly. |

| KI-4 | Male; 53 years old; ethnic Chinese (second generation). Freelancer. From one of the first Chinese families to arrive in Seville (a city in South of Spain). Knows the history of Chinese immigration in Seville and the changes over the years. |

| KI-5 | Male; 41 years old; Spanish. Economist and entrepreneur. Expert in Spanish-Chinese relations. Business manager of the Chinese population. A very relevant individual to the Chinese business community. Has several Chinese friends and travels frequently to China. |

| KI-6 | Male; 18 years old; ethnic Chinese (second generation). Medical student. He was born in Spain, but his whole family is Chinese. He is the youngest informant to provide an overview of the relationship with the immigrant family, the acculturation aspects, the contrast between Western and Eastern cultures, and access to healthcare. |

| KI-7 | Female; 49 years old; born in China. Director of the Chinese Cultural Center and Chinese language teacher; 23 years in Spain. She is responsible for promoting cultural and social activities among the Chinese immigrant community, having full interaction with this population. |

KI: key informant.

The interview script was adapted from the theoretical framework of the quantitative questionnaire. The interview included questions such as: What services do Chinese immigrants use when they have a health problem? What are the reasons and barriers for using the Spanish health services? How would they define the concept of “health” in the Chinese context? What type of services and resources do they have in China? What are the differences between healthcare in China and Spain? Is another type of treatment or medication used? How do they think the local health system could adapt to meet the needs of the Chinese community?

- 3)

Data analysis

The qualitative analysis was carried out following these steps: familiarization with the data; generation of categories; search, review, and definition of themes; and final report.

The data obtained was captured through audio recording, and the use of a field diary. Transcription, literal reading, and theoretical manual categorization were performed. The coded data from each participant were examined and compared with the data from all the other participants to develop categories of meanings. Three main themes were then defined to reflect all of these categories: “Use of health services”, “Contrast between the Chinese and Spanish health systems”, and “Improvements in the Spanish health services to increase their use”. A final report was prepared with the statements of the key informants indicated by “key informant number” and the participant's informal conversations “C-questionnaire number, sex, age”.

ResultsQuantitative phase- 1)

Sample characteristics

The sample consisted of 133 Chinese immigrants, of whom 61.7% were women with a mean age of 30.7 years and an average length of residence in Spain of 11.3 years. The majority of participants (78.3%) were from Zhejiang Province, China; 61.7% were married and had secondary education (71%) (Table 2).

- 2)

Use of health services

Sample characteristics.

| Variables | MaleM (SD) | FemaleM (SD) | TotalM (SD) | Statistics p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 33.1 (7.2) | 29.2 (7.4) | 30.7 (7.6) | p=0.003 |

| Years residing in Spain | 12.7 (5.7) | 10.4 (5.5) | 11.3 (5.7) | U=4774.5 p=0.017 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Sex | 51 (38.3) | 82 (61.7) | 133 (100) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 11 (21.5) | 34 (41.5) | 45 (33.8) | χ2=7.35 |

| Married | 36 (70.6) | 46 (56.1) | 82 (61.7) | p=0.062 |

| Living with a partner (not married) | 3 (5.9) | 2 (2.4) | 5 (3.8) | |

| Divorced | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Level of education | ||||

| Secondary or lower | 41 (80.4) | 62 (75.6) | 103 (77.4) | χ2=0.41 |

| Vocational or university | 10 (19.6) | 20 (24.4) | 30 (22.6) | p=0.521 |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed | 50 (98.0) | 78 (95.1) | 128 (96.2) | χ2=0.74 |

| Unemployed | 1 (2.0) | 4 (4.9) | 5 (3.8) | p=0.649 |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3 shows the use of the health system. Most of the participants had health coverage at the time of the study, public (87.2%) and/or private (31.7%), and only 2.3% had no health insurance. In the previous year, 51.1% had visited a doctor, 33.8% had visited the emergency department, and 8.3% had been hospitalized. The main reasons for hospitalization were pregnancy (37.5%) and surgery (25%). However, 20% of the sample reported that they had never visited a doctor since living in Spain. In the previous month, 23.3% had visited a doctor, mainly due to acute health problems (58%) and routine check-ups (32.3%). The visit to the doctor took place in public primary care centers (37%), private health centers (37%), and public emergency services (26%).

Use of the health system in Spain according to sex.

| Characteristic | Male (n=51) | Female (n=82) | Total (n=133) |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Visit to the doctor (previous year) | 23 (45.1) | 45 (54.9) | 68 (51.1) |

| Visit to the doctor (previous month) | 12 (23.5) | 19 (23.2) | 31 (23.3) |

| Main reason for visit (previous month) | |||

| Acute health problem | 7 (13.7) | 11 (13.8) | 18 (13.5) |

| Check-ups | 4 (7.8) | 6 (7.3) | 10 (7.5) |

| Accidents | 1 (2) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Sick leave or discharge | 0 0 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (0.75) |

| Where did this last visit take place? | |||

| Public primary care center | 3 (5.9) | 7 (8.5) | 10 (7.5) |

| Public emergency services | 2 (3.9) | 5 (6.1) | 7 (5.3) |

| Private health center | 4 (7.8) | 6 (7.3) | 10 (7.5) |

| No response | 3 (5.9) | 1 (1.2) | 4 (3) |

| Hospitalizationsa | 4 (7.8) | 7 (8.5) | 11 (8.3) |

| Emergency services useda | 17 (33.3) | 28 (34.1) | 45 (33.8) |

| Type of emergency services useda | |||

| Public hospital | 9 (17.6) | 14 (17.1) | 23 (17.3) |

| Private hospital | 4 (7.8) | 7 (8.5) | 11 (8.3) |

| Public primary care center (ER) | 3 (5.9) | 6 (7.3) | 9 (6.8) |

| No response | 1 (2) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.5) |

| Other special health services useda | |||

| Radiology | 11 (21.6) | 10 (12.2) | 21 (15.8) |

| Dentistry | 10 (19.6) | 23 (28) | 33 (24.8) |

| Homeopathy, naturopathy, and acupuncture | 4 (7.8) | 8 (9.8) | 12 (9) |

| Why didn’t you receive health care despite needing it? | |||

| Long waiting time to be attended (focus on the system) | 4 (7.8) | 11 (13.8) | 15 (11.3) |

| Lack of personal time (focus on the person) | 11 (21.6) | 12 (14.6) | 23 (17.3) |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Days of hospitalizationa | 5.5 (3.5) | 2 (0.9) | 2.9 (2.2) |

| Number of visits to emergency servicesa | 1 (0) | 1.26 (0.56) | 1.15 (0.4) |

M: mean; SD: standard deviation.

As for the inferential analysis, visiting the doctor during the previous year was not associated with sex or length of residence in Spain, but with age (U=951.5; p=.02). Younger immigrants (M=29.8 years; SD=7.5) visited the doctor more frequently than older immigrants (M=33.6 years; SD=7.6).

In terms of the healthcare received, 99.2% reported that they had not received specialized healthcare (i.e. home-based care, domestic help, or special transport services) and 8% stated that they had not received healthcare despite needing it. Lack of time was the main reason for not receiving healthcare, followed by the long waiting time.

It was found that there was no sex difference in the relationship between waiting hours and not receiving medical care in general. However, when considered separately, lack of time due to work was associated with medical care (χ2 (1)=7.9; p=0.005) in men (odds ratio [OR]=7.7; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 1.67-35.5), whereas lack of time due to childcare was associated with medical care (χ2 (1)=6.6; p=0.01) in women (OR=12; 95%CI: 1.6-91.1).

Qualitative phaseTable 4 shows the main ideas included in the verbatim quotations. Regarding “Use of health services”, the key informants and the informal conversations of the participants showed that, among the Chinese community, employed immigrants frequently use public emergency services, whereas students and self-employed workers use private insurance.

Distribution of verbatim quotations.

| Themes | Verbatim quotations |

|---|---|

| Use of health services | (KI-3) “The rich prefer private health care, but the majority, in general, turn to public health care. They usually use emergency services because they think they are faster. Of course, you get an immediate solution (..)”.(C-100, woman, 25 years) “Have you ever heard that the Chinese don’t get sick? If a Chinese individual goes to the hospital, it means that that person must be very sick. In China, since we pay for doctors, we don’t visit them that often.”(KI-1) “They prefer to self-medicate with what they brought back from China and follow the recommendations of their friends and relatives. They have tiger balm.... or use bá guàn, which are suction cups (...). They identify foods with elements of traditional Chinese medicine, classify them in different ways, and also use them as a way of restoring internal balance.”(C-85, man, 37 years) “To treat my hepatitis, I take the prescribed medication, but also Asian natural medicine (…). I also visit an acupuncturist. He's not open to the public, he works at home. He is very good, and I prefer him to Western medicine.” |

| Contrast between the Chinese and the Spanish health systems | (KI-2) “Western medicine is viewed with suspicion because it can solve the problem in the short term but, at the same time, it can cause another (...). The way of looking at the ailments, the solutions, and the remedies; everything is totally different.”(KI-6) “Advantages in China: you don’t have to wait long; if you have money, you pay and they are usually very quick to carry out any intervention. Here, as Social Security stands, there are a lot of people waiting to be attended.”(KI-5) “In China, the good doctor is the one who does you no harm, not the one who cures you (...). The Chinese go less often than we do to the doctor. In China you can find doctors who trade in prescriptions. They do not doubt that the physicians’ judgment here is the most honest and best for them, but they often question the knowledge or type of diagnosis being Western.” |

| Improvements in the Spanish health services | (KI-2) “Language is paramount (...). I don’t think much more adaptation is needed once there's software available that collects the main ailments, diagnoses, and treatments, a simultaneous interpreter, and Internet applications with which they can request appointments according to the specialty they need and do everything online provided they are adapted to Chinese digital systems.”(KI-7) “I believe that the established healthcare process or protocol is not right (...). In the end, they don’t go to the doctor because they have to wait for many hours, they waste the whole morning.”(C-6, man, 39 years; C-131, woman, 27 years) “If you go to an appointment at 11 o’clock, you will stay there at least until noon. I’m working, so I can’t afford to waste that much time.”(KI-3): “If there were shorter waiting times and doctors were more flexible in their treatment and diagnosis, it would also make it much easier for them.”(KI-4) “You come to Spain and … you can’t talk to the doctor, you can’t express yourself, you don’t know what medications they are going to give you... then you feel helpless. Many of them (immigrants) go back to China when they get sick because they speak the language there, they know people and hospitals; they feel safer.” |

C: conversation; KI: key informant.

However, all of the informants agreed that Chinese immigrants should not be considered frequent users of the public health system in Spain. Most Chinese immigrants, older adults in particular, prefer to use traditional Chinese medicine as their first treatment rather than visiting a doctor.

Interestingly, during the interviews, immigrants offered several traditional medicines to the interviewer with labels in Chinese. It demonstrates the familiarity and confidence this population has in traditional Chinese medicine compared to Western medicine. In “Contrast between the Chinese and Spanish health systems”, they consider Western medicine to be curative and very symptom-centered, which differs from the preventive nature of traditional Chinese medicine.

“Improvements in the Spanish health services” includes the accessibility barriers, such as the incompatibility of schedules with the resources offered. Chinese immigrants prioritized their duty to work as a primary necessity over regular medical care. Because of the intense working hours this group is subjected to, they tend to regard visiting the doctor for health reasons as a “waste of time”.

It was easy to see that these immigrants spent most of their time in their businesses working and had little time for other things such as seeing a doctor. A Chinese immigrant (conversation 86, woman, 44 years) had a fibular fracture a couple of months earlier, remaining in pain and having difficulty standing. Despite these constraints, he continued to work and, because of his work, was unable to go to rehabilitation.

Their statements also reflect another element that hinders access to health services: language barriers, so that the community itself establishing its own resources, such as having children or young people accompany adults to facilitate the translation and understanding of health information (conversation 113, woman, 29 years; conversation 120, man 19 years).

The trips to China in order to use the Chinese healthcare system are common among adults (conversation 66, woman, 37 years; 101, woman, 44 years) and those who do not have access to healthcare (conversation 127, man, 40 years).

In all statements, communication and waiting times are highlighted as major barriers to accessing health services.

It was also noted that some form of information campaign targeting the Chinese community was an important strategy to minimize the lack of accessibility. Some information examples were how the service works, where they have to go, which doctor is responsible for them (key informant 4), as well as other more specific aspects, such as adapting rooms for them and fitting them with kettles, since the Chinese population consumes mainly hot water (conversation 85, man, 37 years).

The proposals to improve health services are undoubtedly an attempt to resolve or eliminate the factors that hinder access and generate unequal use of resources by the Chinese population. However, most informants acknowledge that health professionals still pay little attention to these cultural differences.

DiscussionTo the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study with a Chinese immigrant sample carried out in Spain.24,29,31 In relation to accessibility, labor regulations in Spain imply being a beneficiary of the National Health System. This can make access to health services difficult for some immigrant groups with higher unemployment rates, such as Latin Americans (23%).32 Among Chinese immigrants, the unemployment rate is almost non-existent. As a result, there is a high rate of people insured in the National Health System in our study33 and who had their own private insurance.34 This contributes to reducing health expenditure and overcoming administrative barriers and waiting times.

Therefore, the ease of access does not explain why the use of health services by Chinese immigrants in our study (51%) was lower than the levels found in the native Spanish population in National Health Survey of Spain (87.4%).30 Nevertheless, Chinese immigrants make slightly greater use of acute care services, which may be the result of acute health problems and incompatibility between working hours and the availability of health services.34,35 Since this is considered a major problem, nurses must be prepared to provide care from different perspectives while taking cultural diversity into account.36

In addition, approximately 20% of our sample claimed not to have ever visited a doctor, data which coincide with the results obtained by García,26 but which differ from those of the native population.30 Our findings do not support previous data showing that young immigrants tend to be less likely to use health services.15,37 The possible reasons for our findings may be explained as follows. First, older Chinese immigrants prefer to have medical examinations and use health services in China, having a tendency to preserve their cultural identity38 and using Western medicine as a last resort.39 Secondly, the process of acculturation also produces significant differences among the immigrant population, in a sense that younger Chinese immigrants exhibit behaviors more similar to those of the native population.

In relation to the qualitative analysis, the informants indicated a lower perception of the use of the health system by Chinese population due to several barriers: lack of personal time (both for work and childcare) and long waiting times to ensure adequate care, aspects that have been highlighted in other studies.34 Coinciding with the results of our study, some authors also point out that language constraints,35 work routine, and the use of complementary therapies40 can also be sources of conflict for the nursing staff, causing mutual distrust,6 as well as medical errors,41 and can lead to health inequalities in the immigrant population.17,42

Finally, the Chinese population in Seville proposes measures to improve the healthcare of the immigrant population, such as the incorporation of cultural mediators, health guides in different languages,29 the creation of spaces for dialogue with associations of immigrants, and the training of nurses in interculturality.36 Other proposals consist of incorporating information and communication technologies,43 developing protocols for welcoming and attracting users, and including menus and culinary characteristics from other cultures.44

This study has some limitations. First, a convenience sample was used, making it difficult to infer that our sample was representative of the Chinese community in Andalusia or in Spain. Nevertheless, the results are consistent with official data and other studies. Second, language barriers could be at the root of some communication difficulties and some refusals to participate, despite the fact that, in this study, three different languages were used for the same questionnaire in order to be more inclusive. Although Chinese immigrants are young middle-aged, future studies should extend the age of the participants and incorporate ethnic Chinese (Chinese of second generation) to detect differences due to the acculturation.

In conclusion, lower use of health services was found among Chinese immigrants in Seville, Spain as compared to the native population. Immigrants tend to make greater use of acute care services and only one out of five immigrants had never visited a doctor. The most common barriers to accessing health care were language barriers, waiting times, incompatibility with daily tasks, and traditional Chinese medicine use. Understanding these demands and adapting them to the healthcare system may help immigrants to trust their providers, thus increasing the use of health services and improving their treatment.

Health accessibility problems have an impact on vulnerable groups, such as immigrants. Studies indicate that the immigrant population has a worse perception of healthcare than the native population. Immigrant populations are underrepresented in health-related studies and in national health surveys.

What does the study add to the literature?In-depth knowledge about the most common barriers to accessing health for the Chinese population in Spain. Also, this study analyzes the use of health services by Chinese immigrants in Spain. The results may influence the design and implementation of more equitable health policies. In addition, managers of public health services could incorporate the demands expressed, notably the need for linguistic adaptations or the inclusion of treatments based on traditional Chinese medicine.

Carlos Álvarez-Dardet.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsStudy conception and design: BBR, SBT; Data collection: BBR; Data analysis and interpretation: SBT, GL; Drafting of the article: BBR, GL, SBT; Critical revision of the article: BBR.

FundingThis research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestNo conflict of interest has been declared by the authors.