To assess the levels of a tobacco-specific nitrosamine (NNAL) in non-smokers passively exposed to the second-hand aerosol (SHA) emitted from users of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes).

MethodWe conducted an observational study involving 55 non-smoking volunteers divided into three groups: 25 living at home with conventional smokers, 6 living with e-cigarette users, and 24 in control homes (smoke-free homes). We obtained urine samples from all volunteers to determine NNAL.

ResultsWe detected NNAL in the urine of volunteers exposed to e-cigarettes (median:0.55 pg/mL; interquartile range: 0.26-2.94 pg/mL). The percentage of urine samples with quantifiable NNAL differed significantly among the three groups of homes: 29.2%, 66.7% and 76.0%, respectively (p=0.004).

ConclusionsWe found NNAL nitrosamine in urine samples from people exposed to SHA from e-cigarettes. However, these results could be confirmed with more studies with larger sample sizes.

Evaluar los niveles de nitrosamina específica del tabaco (NNAL) en no fumadores expuestos pasivamente al aerosol emitido por usuarios de cigarrillo electrónico.

MétodoEstudio observacional de una muestra de 55 voluntarios no fumadores divididos en tres grupos: 25 que vivían en una casa con un fumador de tabaco convencional, 6 que vivían en una casa con un usuario de cigarrillo electrónico y 24 que vivían en casas controles (hogares libres de humo). Se obtuvo una muestra de orina de todos los voluntarios para determinar las concentraciones de NNAL.

ResultadosSe detectaron valores de NNAL en los voluntarios expuestos al cigarrillo electrónico (mediana: 0,55 pg/ml; rango intercuartílico: 0,26-2,94 pg/ml). El porcentaje de voluntarios con concentraciones cuantificables de NNAL fue estadísticamente diferente entre los tres grupos de casas: 29,2%, 66,7% y 76%, respectivamente (p=0,004).

ConclusionesSe encontraron valores de NNAL en los no fumadores expuestos pasivamente al aerosol del cigarrillo electrónico. Estos resultados tienen que confirmarse con muestras más grandes.

As electronic cigarettes (e-cigarette) use has been grown, more concerns have appeared about the exposure of bystanders to secondhand aerosol (SHA) from these devices. This exposure results when the aerosol inhaled by users (firsthand aerosol) is exhaled into the air where it may be breathed by non-users.1 This exposure is worrying because several studies have found toxic and carcinogenic substances in the aerosol (both firsthand and secondhand) generated by e-cigarettes.1,2

Tobacco-specific nitrosamines have been found in the aerosol generated by e-cigarettes3,4 and also in some brands of e-cigarette liquids,5,6 although not all of the studies have detected tobacco-specific nitrosamines in the samples studied,7 a finding that indicates that important differences between brands may exist. Despite the potential presence of toxic substances in these aerosols, exposure to SHA from e-cigarettes has received scant attention according to a recent systematic review.2

For these reasons, we conducted the present study to assess the levels of NNAL, nitrosamine associate with lung cancer,8 in urine samples in a group of non-smokers exposed to SHA from e-cigarette users in their homes under real-life conditions. Moreover, we compared these concentrations with those of non-smokers passive exposed to conventional cigarettes in their homes and with those of non-smokers not exposed to aerosol from e-cigarettes neither conventional cigarettes in their homes.

MethodWe conducted a study of passive exposure to electronic and conventional cigarettes in real-use conditions. A tobacco-specific nitrosamine (NNAL) was determined in urine samples from a group of volunteers. We recruited a convenience sample of 55 non-smoking volunteers from different homes, distributed as follows: 25 living at home with conventional smokers, 6 living with e-cigarette users, and 24 from control homes (without the presence of either conventional smokers or e-cigarette users). We also enrolled the 6 e-cigarette users who lived with the non-smoking volunteers. Participants living with e-cigarette users or smokers, and the e-cigarette users, provided self-reported data affirming that their only source of exposure to SHA from e-cigarette or tobacco smoke during the one-week study period was in their home and also confirmed that they did not use any tobacco products. These were the conditions for study inclusion that volunteers (non-smokers and e-cigarette users) agreed to at study enrolment. The self-reported lack of exposure in settings other than their homes (work, leisure time, and transport) was confirmed by a personal interview. In addition, all volunteers, including the 6 e-cigarettes users, declared that they did not use other tobacco products or nicotine replacement therapy during the study period. This pilot study is part of a large project which the main objective is to assess the impact of Spanish legislations and the passive exposure to secondhand smoke of conventional cigarettes at home. We conducted this pilot study due to the increasing popularity of the e-cigarettes and the lack of evidence worldwide about passive exposure to SHA from e-cigarettes. The fieldwork was conducted in Barcelona, Spain, in 2012.

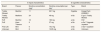

The characteristics of the e-liquids and e-cigarettes used in this study are described in Table 1.

Characteristics of the e-liquids and e-cigarettes in this study.

| E-liquid characteristics | E-cigarettes characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brand | Flavour | Nicotine concentration (mg)a | Nicotine consumption per dayb | Type | Brand |

| Totally Wicked | Menthol | 11 | 62.7 mg | Cigalike | KangerTech KR808D-1 |

| Totally Wicked | Marlboro | 24 | 48 mg | e-Go | E-go C Totally Wicked |

| Puff | Menthol | 18 | 180 mg | e-Go | Puff |

| Puff | Keen Tobacco | 9 | 27 mg | e-Go | e-Go-T Upgrade Joyetech |

| Free Life | Mint | 6 | 19.2 mg | e-Go | e-Go-T Joyetech |

| Unknown | Mint | 6 | 12.85 mg | e-Go | Unknown |

We obtained urine samples for NNAL analysis by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry with multiple reaction monitoring (LC/MS/MS). We measured the NNAL concentration in picograms per milligram of creatinine (pg/mg) because the NNAL concentrations were adjusted for creatinine. The limit of quantification (LOQ) of NNAL was 0.25 pg/mg in 5mL of urine for a 1mg/mL of creatinine excretion.

Data analysisWe calculated the percentage of the volunteers with NNAL concentrations over the LOQ. For the samples with NNAL concentrations below the LOQ, we assumed the half of the LOQ value to compute the medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Given the skewed distribution of NNAL we compared the concentration among three types of homes with the Kruskal Wallis test. Then, we compared the concentration of NNAL among groups by means of the Chi square test and the Wilcoxon test for independent samples. We also calculated the Spearman correlation among NNAL concentrations of the non-smokers exposed to e-cigarettes and users of e-cigarettes who lived with them.

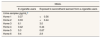

ResultsStatistically significant differences were found among the three groups of homes in the percentage of volunteers with quantifiable levels of NNAL in urine: 29.2%, 66.7%, and 76% (Table 2). After adjusting for multiple comparisons, differences in NNAL urine concentration were on the borderline of statistical significance between non-smokers in control homes and those exposed to tobacco smoke at home (Table 2).

Percentages of samples with detectable levels of NNAL and median (pg/mL) and interquartile range of NNAL in urine samples of the non-smokers volunteers according to passive exposure at home (non-exposed or control homes, exposed to secondhand aerosol from e-cigarettes users, and exposed to tobacco smoke).

| NNAL in urine samplesa | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage of samples with detectable NNAL | Median (IQR) | |

| Non exposed (control homes) | 24 | 29.2% | 0.33 (0.16 - 0.51) |

| Exposed to e-cigarettes’ aerosol | 6 | 66.7% | 0.55 (0.26 - 2.94) |

| Exposed to conventional cigarettes | 25 | 76.0% | 0.46 (0.29 - 1.11) |

| p-valueb | 0.004 | - | |

| p-valuec | - | 0.040 | |

| p-valued | - | 0.129 | |

| p-valuee | - | 0.017 | |

| p-valuef | - | 0.865 | |

IQR: interquartile range.

Comparison among volunteers from the three types of homes (non-exposed or smoke-free homes, exposed to e-cigarettes’ aerosol, and conventional cigarettes) by Kruskal Wallis test.

Comparison between volunteers from smoke-free homes (control homes) and e-cigarettes homes by Wilcoxon test for independent samples.

As shown in Table 3, we quantified traces of NNAL in the urine samples of four out of the six volunteers exposed to SHA from e-cigarette users. Spearman's correlation of the NNAL levels in urine of the e-cigarettes users and the volunteers exposed to SHA from e-cigarette users was 0.943 (p=0.005).

Levels of NNAL in the samples of urine of the e-cigarettes user and non-users exposed to secondhand aerosol from e-cigarettes users.

| NNAL | ||

|---|---|---|

| E-cigarette users | Exposed to secondhand aerosol from e-cigarette users | |

| Urine samples (pg/mL)a | ||

| Home 1 | 0.37 | <0.56 |

| Home 2 | 0.33 | <0.44 |

| Home 3 | 6.1 | 3.0 |

| Home 4 | 0.42 | 0.44 |

| Home 5 | 5.3 | 0.67 |

| Home 6 | 9.4 | 2.9 |

From six e-cigarette users, NNAL was quantifiable in the urine sample (median: 2.86 pg/mg; IQR: 0.36-6.92 pg/mL) (data not shown).

DiscussionOur results show that there are quantifiable levels of NNAL in urine among bystanders exposed to SHA from e-cigarette users at home. Moreover, we also found a strong correlation between NNAL levels in urine among e-cigarette users and those of the non-smokers exposed to SHA at home from e-cigarette users. A previous study conducted in 698 individuals (532 of them non-smokers) also found levels of NNAL in saliva among non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke.9

Vogel et al.10 found that the levels of NNAL in urine (without adjusting for creatinine) ranged from 6.27 to 12.54 pg/mL, among non-smokers exposed to secondhand smoke from conventional cigarettes. In our study, the levels were lower in participants who were passively exposed to e-cigarettes (median: 0.47 pg/mL; range: 0.125-3.2 pg/mL) and to conventional cigarettes (median: 0.52 pg/mL; range: 0.125-8.3 pg/mL). These differences could be explained partially by the differences on the sample size of both studies and the inclusion criteria of our study (at home was the only source of exposure of our non-smokers volunteers and e-cigarette users in the last week). Moreover, other potential explanation could be the difference in the duration and intensity of exposure among studies, and the measurement bias inter-laboratory. Although the levels of NNAL among non-smokers exposed passively to e-cigarettes are very low8 there is no safety level of exposure and the risk increases with the intensity and duration of exposure.11,12

The average NNAL concentration in urine (unadjusted for creatinine) of smokers is around 300 pg/mL.13 We also found levels of NNAL in users of electronic cigarettes (median without adjusting for creatinine: 2.6 pg/mL; range: 0.33-9.7 pg/mL). Compared to smokers, these results are orders of magnitude lower10,13 but this magnitude was similar to those found in e-cigarette users in a previous study.14

Our results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of volunteers exposed to e-cigarette users at home and the differences brands of e-cigarettes. In addition, although one inclusion criterion was that participants’ only permitted exposure to smoking during the study period was at home, we cannot be sure that participants’ did not receive any additional unreported exposure. In an effort to avoid this limitation all participants did not use nicotine replacement therapy and they were instructed to avoid exposure to e-cigarettes and conventional cigarettes except at home.

In conclusion, we found quantifiable levels of NNAL in urine samples of non-smokers passively exposed to SHA from e-cigarette users. However, these results could be confirmed with more studies.

Interest, popularity and awareness of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) have substantially increased in recent years. As e-cigarette use has been grown, more concerns have appeared about the exposure of bystanders to secondhand aerosol from these devices. This exposure results when the aerosol inhaled by users (firsthand aerosol) is exhaled into the air where it may be breathed by non-users.

What does this study add to the literature?Our results show that there are quantifiable levels of NNAL in urine among bystanders exposed to secondhand aerosol from e-cigarette users in the home. We also found a very strong correlation between carcinogenic NNAL levels in urine among e-cigarette users and those of the non-smokers exposed to secondhand aerosol at home from e-cigarette users.

Cristina Linares Gil.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsM. Ballbè and J.M. Martínez-Sánchez conceived the study, conducted the fieldwork, prepared the database, analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. M. Ballbè, J.M. Martínez-Sánchez, X. Sureda, M. Fu, R. Pérez-Ortuño, J.A. Pascual, A. Peruga and E. Fernández contributed substantially to the conception, design, and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved its final version.

AcknowledgementsThe authors wish to thank the 61 volunteers who kindly collaborated in this study. We also thank Bradley Londres for editing the manuscript.

FundingThis project was co-funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Subdirección General de Evaluación, Government of Spain (PI12/01114, PI12/01119, PI15/00291, PI15/00434) co-funded by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and by FEDER funds/European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) — a way to build Europe —. J.M. Martínez-Sánchez is supported by the Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (grant 2017SGR608). M. Fu, M. Ballbè and E. Fernández are supported by the Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (2017SGR139). J.A. Pascual and R. Pérez Ortuño are supported by the Ministry of Universities and Research, Government of Catalonia (grant 2017SGR138). E. Fernández is supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Government of Spain (INT16/00211 and INT17/00103), co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER).

Conflicts of interestNone.