To describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological well-being of adolescents in Catalan schools by gender identity, and to compare coping strategies adopted to manage the health crisis and their relationship with the self-perceived impact of COVID-19 on mental health.

MethodCross-sectional study in educational centres that includes 1171 adolescents over 15 years old from October to November 2021. Multivariate logistic regression models were built to evaluate the association between coping strategies with self-perceived impact of the pandemic on mental health.

ResultsA greater proportion of girls perceived a worsening in mental health than boys due to COVID-19 (36.9% and 17.8%, respectively). The main emotions reported for both girls and boys were worry and boredom. The study found an association between positive coping strategies with less adverse mental health among girls, whereas unhealthy habits were associated with a higher probability of declaring worsening of mental health for both girls and boys.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrated the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being in adolescents and a clearly worse impact on girls. It is important to keep monitoring the medium- and long-term secondary impacts of the pandemic on mental health outcomes of adolescents and to gather information that can improve services for the development of healthy coping strategies during health crises like COVID-19, which include gender perspective.

Describir el impacto de la COVID-19 en el bienestar emocional de adolescentes en Cataluña y comparar las estrategias de afrontamiento adoptadas durante la pandemia y su relación con el impacto autopercibido de la COVID-19 en la salud mental según identidad de género.

MétodoEstudio transversal en centros educativos de Cataluña incluyendo 1171 alumnos/as mayores de 15 años, de octubre a diciembre de 2021. Mediante modelos de regresión logística multivariante se evaluó la asociación entre las estrategias de afrontamiento y el impacto autopercibido de la pandemia en la salud mental.

ResultadosUna mayor proporción de chicas que de chicos percibía un empeoramiento en su salud mental por la COVID-19 (36,9% y 17,8%, respectivamente). Las principales emociones reportadas tanto en chicas como en chicos fueron preocupación y aburrimiento. Se observó una asociación entre estrategias de afrontamiento positivas y una menor probabilidad de declarar un empeoramiento en la salud mental a raíz de la pandemia en las chicas, mientras que otras estrategias relacionadas con hábitos poco saludables se asociaron a una mayor probabilidad de declarar un empeoramiento de la salud mental en chicas y chicos.

ConclusionesEste estudio demuestra el impacto negativo de la pandemia de COVID-19 en el bienestar psicológico de los/las adolescentes, especialmente en las chicas. Es importante seguir monitorizando el impacto de la COVID-19 a medio y largo plazo en la salud mental de los/las adolescentes y disponer de información que pueda mejorar los servicios para el desarrollo de estrategias de afrontamiento saludables durante crisis de salud como la COVID-19 considerando una perspectiva de género.

The SARS-CoV-2 emergency affected health systems globally, compelling governments to implement strategies, like social distancing or confinements, and generating stress, anxiety, and depression which impacted the population well-being, and young people especially.1 In educational settings, measures such as suspending classes and accelerating the use of technology for learning, had an impact on the routines of students and their families.2 Additionally, social distancing reduced the interpersonal interactions and leisure activities of adolescents, who lost social relations with peers, amongst other changes.3 Previous systematic reviews have demonstrated that mental health problems in children and adolescents increased during the pandemic compared to pre-pandemic data, being gender, socio-economic status, previous state of mental and physical health, social support, and consistent routines among the most reported influencing factors.4–8

Several studies have shown gender differences in the response of adolescents to the COVID-19 pandemic, with a worse effect on psychological well-being observed in girls girls.9,10 Reasons cited for the gender differences include a reduction in emotional support from social networks due to social distancing distancing11 and a greater increase in unhealthy lifestyle habits compared to boys.9 Additionally, depression and anxiety increase during puberty, especially among girls,12 which may partially explain these gender disparities. The pandemic highlighted gender differences in mental health that are a reflection of the distinct social processes for youth with different gender identities, as well disparities in mental health that emerge and intensify during this stage of life.13

Effective coping strategies, defined as cognitive and behavioural efforts made to manage situations that are potentially threatening or stressful,14 have been reported in adolescents, such as physical activity, use of social networks and establishing routines.15,16 However, unhealthy coping strategies such as consumption of tobacco, alcohol and/or drugs, or unhealthy eating habits have been identified, although to a lesser extent17. Evidence indicates that positive coping strategies, such as connecting with friends and family members and/or engaging in physical activities, are closely related to better mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic,8 whereas unhealthy coping strategies relate more strongly to greater negative impacts on stress and mental health, Also gender is one of the factors that influences which coping strategies are adopted to confront stress.10,18 A previous study in Spain on a sample of university students showed that men resorted to physical exercise during the pandemic, while women listened to more music and watched more television.19

The COVID-19 Sentinel Schools Network of Catalonia (CSSNC), main objective was to monitor and evaluate the COVID-19 situation and its impact in educational settings in order to gather evidence for the health policies, prevention and control of SARS-CoV-2 in schools. Since its implementation in 2020, mental health was identified as a priority challenge, leading us to include in the project new research questions to better explore this issue in schools and develop more effective strategies strategies.20

This study aims to describe the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being, defined as “a state of mind in which an individual is able to develop their potential, work productively, and creatively, and is able to cope with the normal stresses of life”,21 in students over 15 years in CSSNC stratified by gender identity. Furthermore, the study aims to compare coping strategies adopted to manage the health crisis by gender and to investigate associations between strategies adopted and a worsening of mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It is essential to explore how girls and boys were coping during the pandemic and what coping strategies positively or negatively influenced changes in mental health to be able to understand the impacts of the pandemic and to better inform appropriate school-based interventions, creating a safe and supportive environment that responds to their specific needs.

MethodStudy design and participants selectionThis is a cross-sectional study in 16 educational centres in Catalonia part of the CSSNC Project during 2021-2022.20 Although it was an opportunistic sample, epidemiological, sociodemographic characteristics, and type of school (public, private, or chartered) were considered to assure heterogeneity. For the objectives of this study, students aged 15-19 years-old were included. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the IDIAP Jordi Gol i Gurina Foundation on 17 December 2020 (20/192-PCV). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data collectionData collection took place from October-November 2021 through a questionnaire developed on the REDCap platform, or in paper when necessary. Each school was responsible to send a link containing the informed consent and the questionnaire available in Catalan, Spanish and English to teaching and non-teaching staff and students. Students over 15 years old signed the informed consent and completed the questionnaire by themselves. Response rate was 53% and 23% for staff and students, respectively.

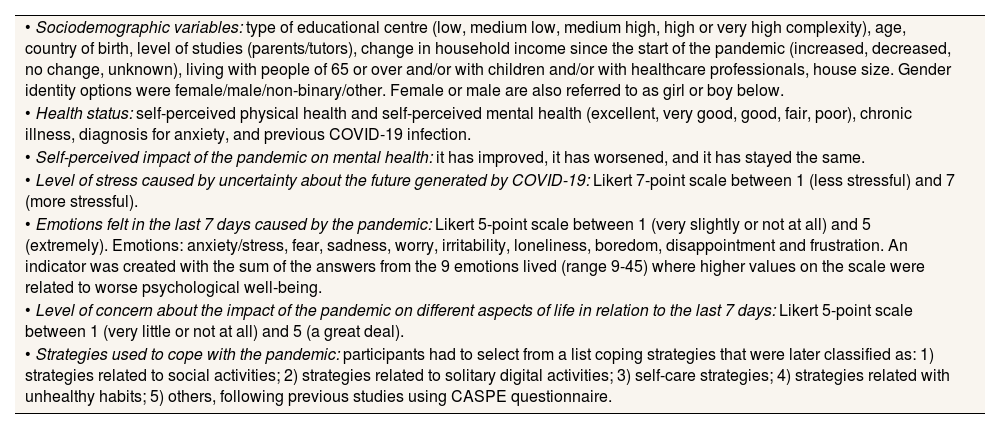

VariablesThe questionnaire including sociodemographic and health status variables was based on the WHO/Europe recommendation.22 The questions on impact of COVID-19 on psychological well-being of students and the coping strategies adopted were adapted from sections from the CASPE questionnaire.23 The full list of variables is presented in table 1.

List of variables included in the questionnaire.

| • Sociodemographic variables: type of educational centre (low, medium low, medium high, high or very high complexity), age, country of birth, level of studies (parents/tutors), change in household income since the start of the pandemic (increased, decreased, no change, unknown), living with people of 65 or over and/or with children and/or with healthcare professionals, house size. Gender identity options were female/male/non-binary/other. Female or male are also referred to as girl or boy below. |

| • Health status: self-perceived physical health and self-perceived mental health (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), chronic illness, diagnosis for anxiety, and previous COVID-19 infection. |

| • Self-perceived impact of the pandemic on mental health: it has improved, it has worsened, and it has stayed the same. |

| • Level of stress caused by uncertainty about the future generated by COVID-19: Likert 7-point scale between 1 (less stressful) and 7 (more stressful). |

| • Emotions felt in the last 7 days caused by the pandemic: Likert 5-point scale between 1 (very slightly or not at all) and 5 (extremely). Emotions: anxiety/stress, fear, sadness, worry, irritability, loneliness, boredom, disappointment and frustration. An indicator was created with the sum of the answers from the 9 emotions lived (range 9-45) where higher values on the scale were related to worse psychological well-being. |

| • Level of concern about the impact of the pandemic on different aspects of life in relation to the last 7 days: Likert 5-point scale between 1 (very little or not at all) and 5 (a great deal). |

| • Strategies used to cope with the pandemic: participants had to select from a list coping strategies that were later classified as: 1) strategies related to social activities; 2) strategies related to solitary digital activities; 3) self-care strategies; 4) strategies related with unhealthy habits; 5) others, following previous studies using CASPE questionnaire. |

Differences between proportions according to gender were compared using the Chi-Square, or the exact Fisher's exact test when more than 20% of cells have expected frequencies <5, and differences between means using the Student's t test. Only people identifying as men or women were included in the analysis because the small number of participants identified themselves as non-binary or other (12 people identified themselves as non-binary and 48 did not want to answer the question).

Logistic regression models were built to evaluate the association between coping strategies with self-perceived impact of the pandemic on mental health, adjusting by gender, house size and type of educational centre according to complexity. The dependent variable “self-perceived impact of the pandemic on mental health” was dichotomized as “it has improved or stayed the same” versus “it has worsened”. Adjusted OR (aOR) were calculated with a confidence interval of 95% (95%CI). The level of statistical significance was established as 0.05. All analyses were carried out using the R program, version 4.1.2.

ResultsOf a total of 1171 participants, 626 (55.7%) identified as women, 478 (42.6%) identified as men, 12 (1.1%) as non-binary and 7 (0,6%) as other gender. Regarding complexity, 166 (14.2%) students were from low complexity schools, 140 (12.0%) medium low complexity, 700 (59.8%) medium high and the rest (14.1%) from high complexity schools.

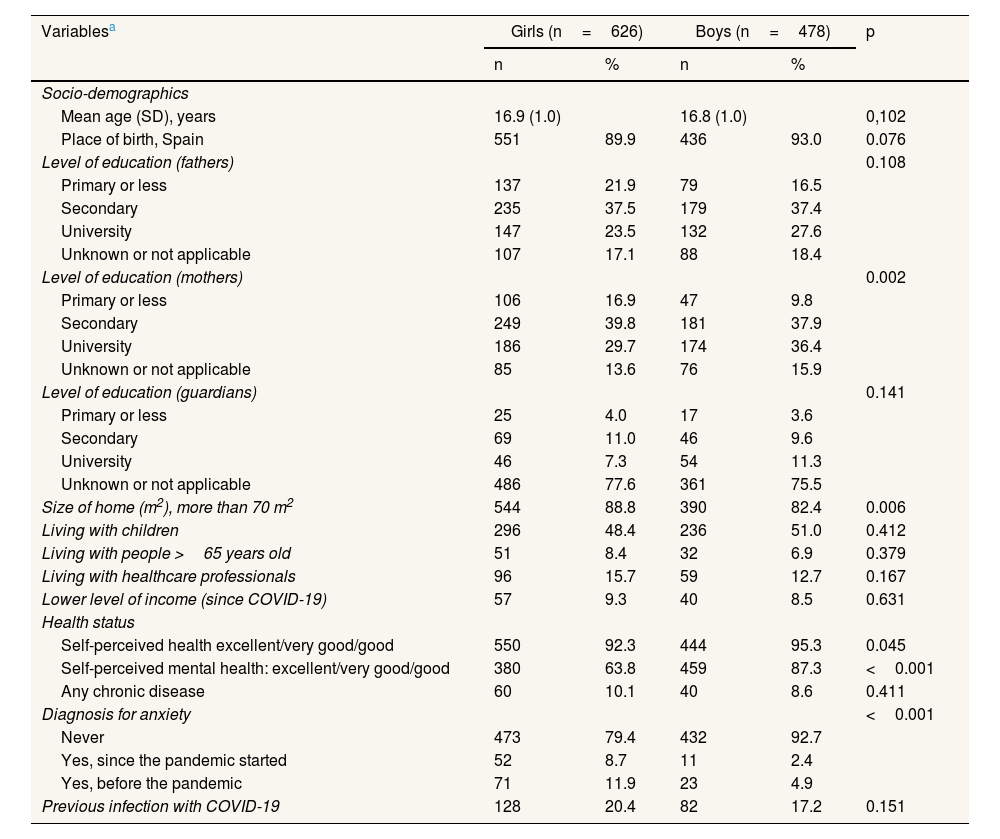

The mean age of participating boys and girls was 16.9 and 16.8 years old, respectively, most were born in Spain (89.9% girls and 93.0% boys), and 9.3% of girls and 8.5% of boys reported a lower level of family income since the start of the pandemic. A higher proportion of boys compared to girls reported a university level of education for their mothers (36.4% boys and 29.7% girls) (Table 2).

Socio-demographic and health status characteristics of the sample according to gender identity.

| Variablesa | Girls (n=626) | Boys (n=478) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Socio-demographics | |||||

| Mean age (SD), years | 16.9 (1.0) | 16.8 (1.0) | 0,102 | ||

| Place of birth, Spain | 551 | 89.9 | 436 | 93.0 | 0.076 |

| Level of education (fathers) | 0.108 | ||||

| Primary or less | 137 | 21.9 | 79 | 16.5 | |

| Secondary | 235 | 37.5 | 179 | 37.4 | |

| University | 147 | 23.5 | 132 | 27.6 | |

| Unknown or not applicable | 107 | 17.1 | 88 | 18.4 | |

| Level of education (mothers) | 0.002 | ||||

| Primary or less | 106 | 16.9 | 47 | 9.8 | |

| Secondary | 249 | 39.8 | 181 | 37.9 | |

| University | 186 | 29.7 | 174 | 36.4 | |

| Unknown or not applicable | 85 | 13.6 | 76 | 15.9 | |

| Level of education (guardians) | 0.141 | ||||

| Primary or less | 25 | 4.0 | 17 | 3.6 | |

| Secondary | 69 | 11.0 | 46 | 9.6 | |

| University | 46 | 7.3 | 54 | 11.3 | |

| Unknown or not applicable | 486 | 77.6 | 361 | 75.5 | |

| Size of home (m2), more than 70 m2 | 544 | 88.8 | 390 | 82.4 | 0.006 |

| Living with children | 296 | 48.4 | 236 | 51.0 | 0.412 |

| Living with people >65 years old | 51 | 8.4 | 32 | 6.9 | 0.379 |

| Living with healthcare professionals | 96 | 15.7 | 59 | 12.7 | 0.167 |

| Lower level of income (since COVID-19) | 57 | 9.3 | 40 | 8.5 | 0.631 |

| Health status | |||||

| Self-perceived health excellent/very good/good | 550 | 92.3 | 444 | 95.3 | 0.045 |

| Self-perceived mental health: excellent/very good/good | 380 | 63.8 | 459 | 87.3 | <0.001 |

| Any chronic disease | 60 | 10.1 | 40 | 8.6 | 0.411 |

| Diagnosis for anxiety | <0.001 | ||||

| Never | 473 | 79.4 | 432 | 92.7 | |

| Yes, since the pandemic started | 52 | 8.7 | 11 | 2.4 | |

| Yes, before the pandemic | 71 | 11.9 | 23 | 4.9 | |

| Previous infection with COVID-19 | 128 | 20.4 | 82 | 17.2 | 0.151 |

SD: standard deviation.

Boys presented a better self-perceived general health compared to girls (95.3% good, very good or excellent for boys, and 92.3% for girls) and better self-perceived mental health (87.3% good, very good or excellent for boys, and 63.8% for girls). Additionally, the percentage diagnosed with anxiety before or after the pandemic started was higher in girls (20.6% girls and 7.3% boys) (Table 2).

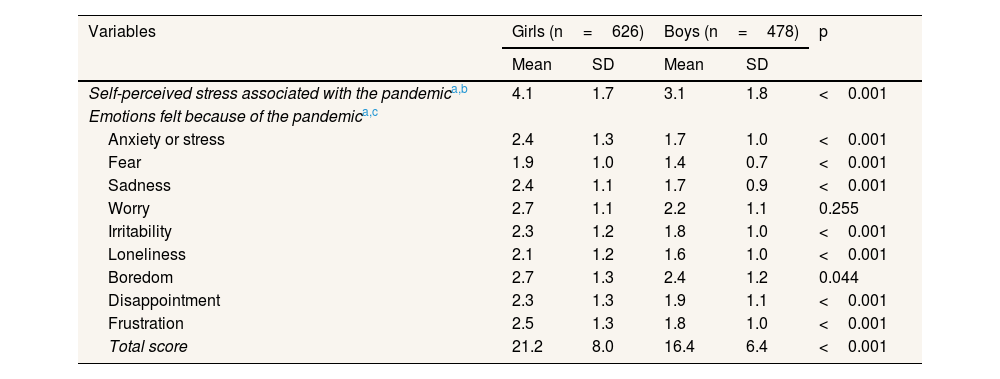

A greater proportion of girls perceived a worsening in mental health due to the COVID-19 compared to boys (36.9% and 17.8%, respectively), while 5.7% of girls and 15.0% of boys perceived their mental health as improved in this same period (p<0.001). Additionally, the level of stress caused by uncertainty about the future generated for COVID-19 was also greater in girls than in boys (M=4.1, standard deviation [SD]: 1.7, and M=3.1, SD: 1.8, respectively) (Table 3).

Level of stress caused by uncertainty about the future generated by COVID-19 and emotions felt by gender identity.

| Variables | Girls (n=626) | Boys (n=478) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Self-perceived stress associated with the pandemica,b | 4.1 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1.8 | <0.001 |

| Emotions felt because of the pandemica,c | |||||

| Anxiety or stress | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Fear | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | <0.001 |

| Sadness | 2.4 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 0.9 | <0.001 |

| Worry | 2.7 | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 0.255 |

| Irritability | 2.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Loneliness | 2.1 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Boredom | 2.7 | 1.3 | 2.4 | 1.2 | 0.044 |

| Disappointment | 2.3 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | <0.001 |

| Frustration | 2.5 | 1.3 | 1.8 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Total score | 21.2 | 8.0 | 16.4 | 6.4 | <0.001 |

SD: standard deviation.

For all the emotions that can generate emotional discomfort, girls had statistically significant higher mean scores than boys, except for worry (Table 3). The main emotions reported for both girls and boys, respectively, were worry (M=2.7, SD: 1.1, and M=2.2, SD: 1.1) and boredom (M=2.7, SD: 1.3, and M=2.4, SD: 1.2), followed by frustration in girls (M=2.5, SD: 1.3) and disappointment in boys (M=1.9, SD: 1.1).

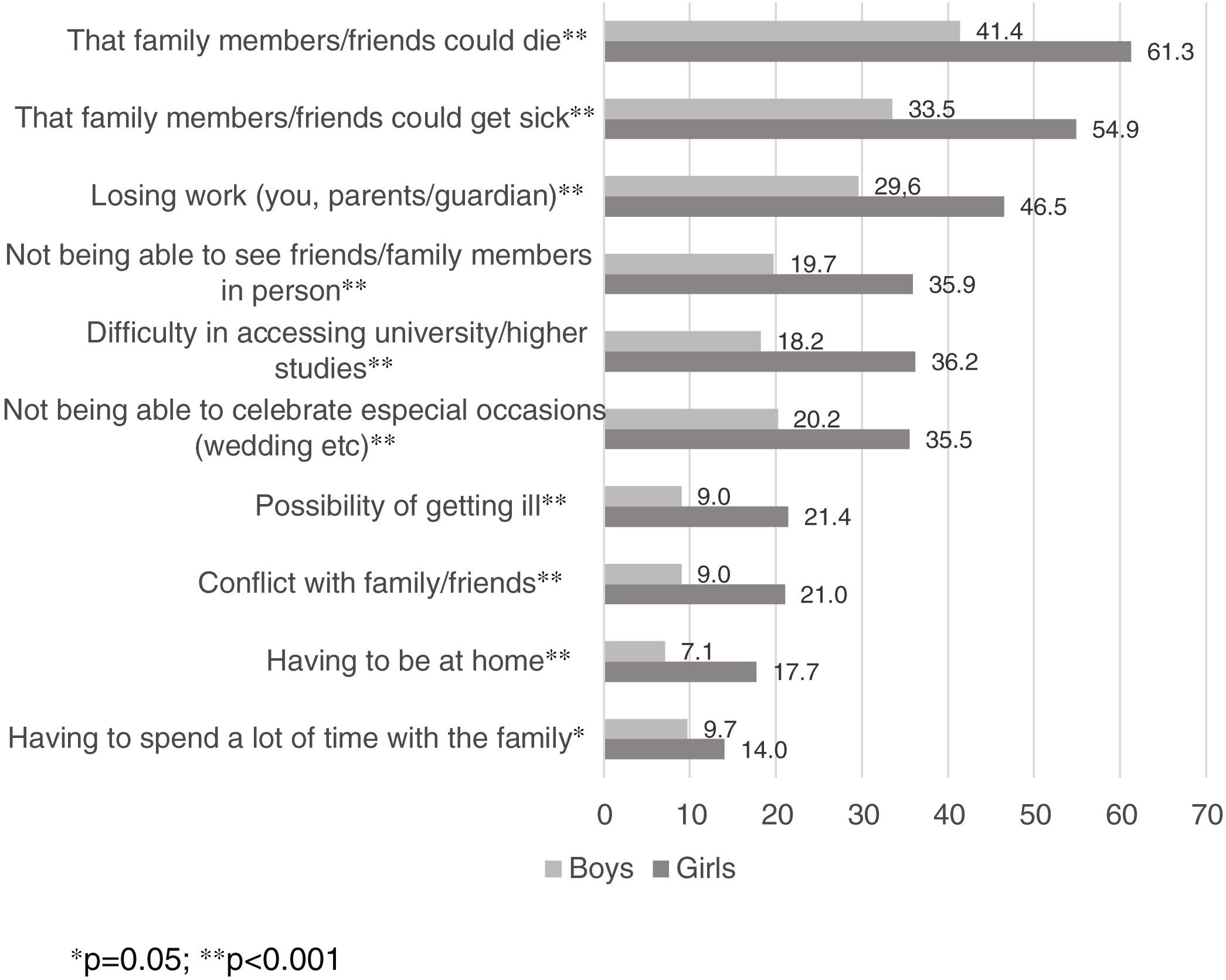

Most of the participants reported a high negative impact of the pandemic caused by the fact that friends or family could die (61.3% girls and 41.4% boys) and/or get sick (54.9% girls and 33.5% boys), together with the fear of losing jobs (themselves or family members) (46.5% girls and 29.6% boys) (Fig. 1).

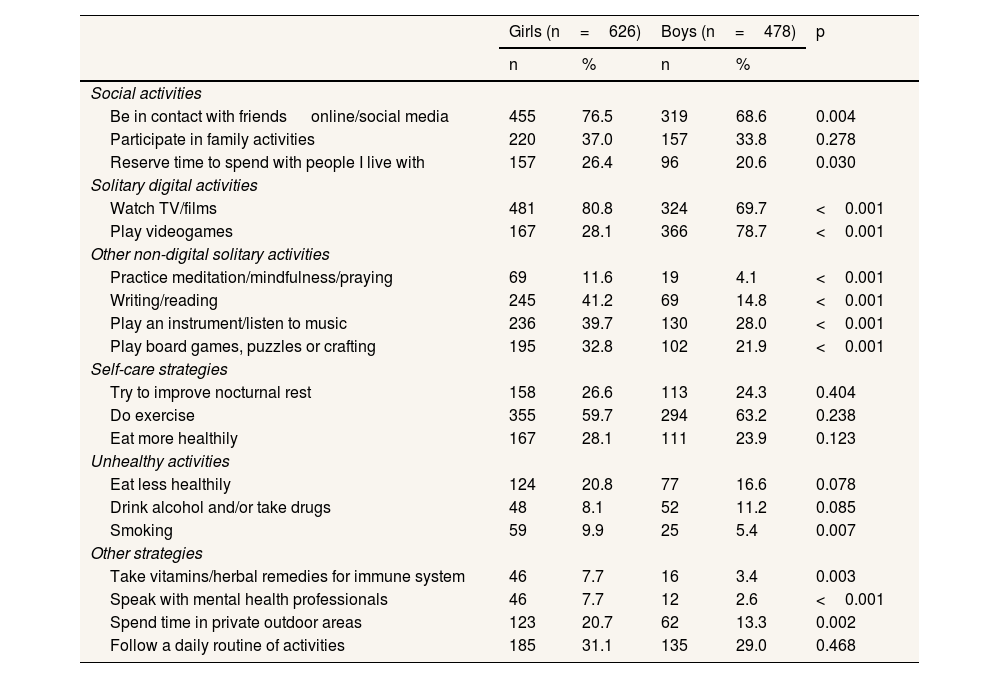

One of the most frequent coping strategies used by adolescents to deal with the pandemic (Table 4) was contact with friends online and/or social media (76.5% and 68.6% in boys and girls, respectively), and other solitary digital activities like watching TV and/or films (80.8% and 69.7% in girls and boys, respectively). On the other hand, playing videogames was an activity mainly reported by boys in comparison with girls (78.7% and 28.1%, respectively). In addition, other social activities related to family such as reserving time to spend with people they lived with were more frequently reported by girls in comparison with boys (26.4% and 20.6%, respectively). More than half the adolescents also referred to self-care strategies like taking exercise (59.7% and 63.2% in girls and boys, respectively), and/or other individual non-digital activities such as reading and/or writing, higher among girls (41.2% girls and 14.8% boys). Amongst unhealthy activities, girls reported smoking as a coping strategy more frequently than boys (9.9% girls and 5.4% boys), while eating less healthily (20.8% girls and 16.6% boys), and consumption of alcohol and/or drugs (11.2% boys and 8.1% girls) were reported similarly by gender. The percentage of girls who had spoken to a mental health professional was higher than boys (7.7% of girls and 2.6% of boys).

Strategies used to cope with the pandemic by gender identity.

| Girls (n=626) | Boys (n=478) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Social activities | |||||

| Be in contact with friends online/social media | 455 | 76.5 | 319 | 68.6 | 0.004 |

| Participate in family activities | 220 | 37.0 | 157 | 33.8 | 0.278 |

| Reserve time to spend with people I live with | 157 | 26.4 | 96 | 20.6 | 0.030 |

| Solitary digital activities | |||||

| Watch TV/films | 481 | 80.8 | 324 | 69.7 | <0.001 |

| Play videogames | 167 | 28.1 | 366 | 78.7 | <0.001 |

| Other non-digital solitary activities | |||||

| Practice meditation/mindfulness/praying | 69 | 11.6 | 19 | 4.1 | <0.001 |

| Writing/reading | 245 | 41.2 | 69 | 14.8 | <0.001 |

| Play an instrument/listen to music | 236 | 39.7 | 130 | 28.0 | <0.001 |

| Play board games, puzzles or crafting | 195 | 32.8 | 102 | 21.9 | <0.001 |

| Self-care strategies | |||||

| Try to improve nocturnal rest | 158 | 26.6 | 113 | 24.3 | 0.404 |

| Do exercise | 355 | 59.7 | 294 | 63.2 | 0.238 |

| Eat more healthily | 167 | 28.1 | 111 | 23.9 | 0.123 |

| Unhealthy activities | |||||

| Eat less healthily | 124 | 20.8 | 77 | 16.6 | 0.078 |

| Drink alcohol and/or take drugs | 48 | 8.1 | 52 | 11.2 | 0.085 |

| Smoking | 59 | 9.9 | 25 | 5.4 | 0.007 |

| Other strategies | |||||

| Take vitamins/herbal remedies for immune system | 46 | 7.7 | 16 | 3.4 | 0.003 |

| Speak with mental health professionals | 46 | 7.7 | 12 | 2.6 | <0.001 |

| Spend time in private outdoor areas | 123 | 20.7 | 62 | 13.3 | 0.002 |

| Follow a daily routine of activities | 185 | 31.1 | 135 | 29.0 | 0.468 |

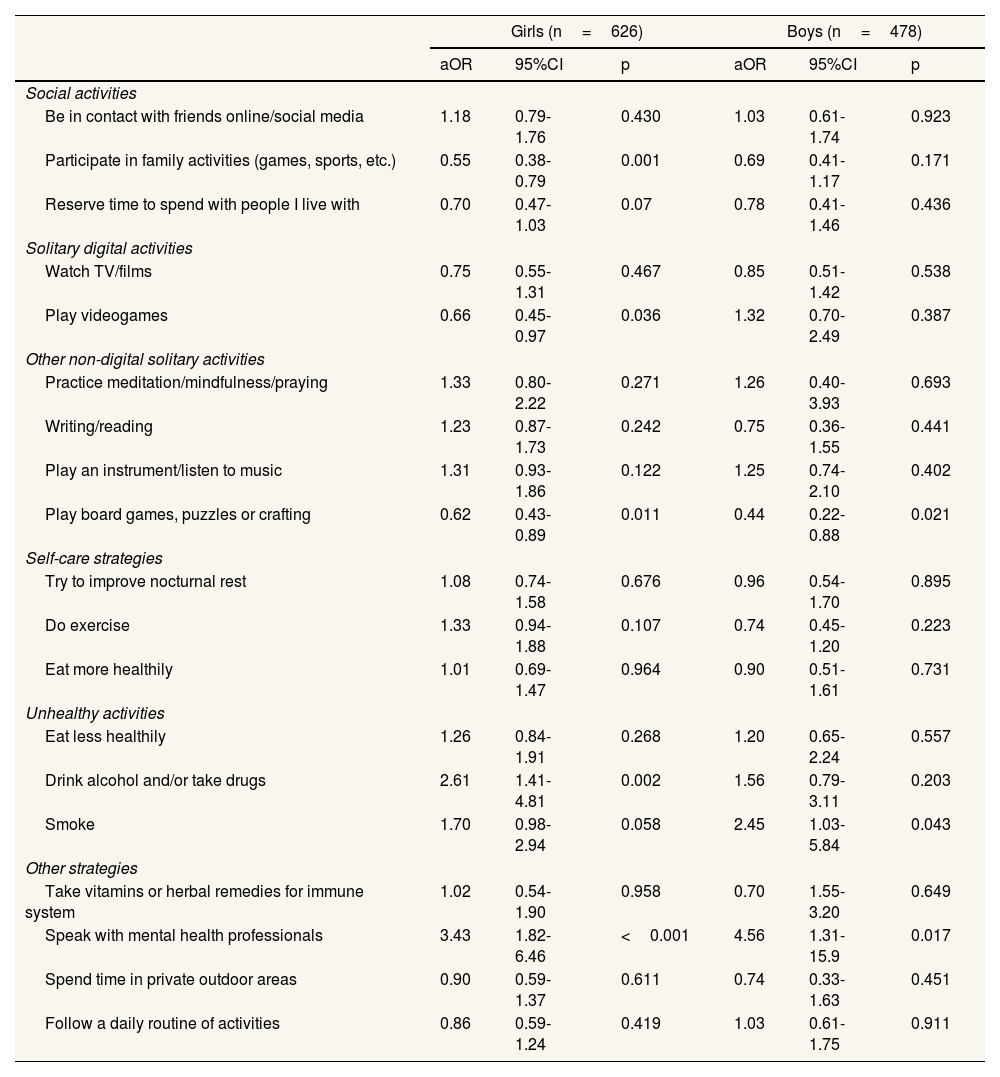

In the adjusted logistic regression analysis, we founded an association between the participation in family activities, such as playing games and/or sports, with a lower probability of declaring worsening of mental health due to the pandemic among girls (OR: 0.55; 95%CI: 0.38-0.79) (Table 5).

Association between strategies to cope with the pandemic and worsening of mental health adjusted by gender identity.

| Girls (n=626) | Boys (n=478) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR | 95%CI | p | aOR | 95%CI | p | |

| Social activities | ||||||

| Be in contact with friends online/social media | 1.18 | 0.79-1.76 | 0.430 | 1.03 | 0.61-1.74 | 0.923 |

| Participate in family activities (games, sports, etc.) | 0.55 | 0.38-0.79 | 0.001 | 0.69 | 0.41-1.17 | 0.171 |

| Reserve time to spend with people I live with | 0.70 | 0.47-1.03 | 0.07 | 0.78 | 0.41-1.46 | 0.436 |

| Solitary digital activities | ||||||

| Watch TV/films | 0.75 | 0.55-1.31 | 0.467 | 0.85 | 0.51-1.42 | 0.538 |

| Play videogames | 0.66 | 0.45-0.97 | 0.036 | 1.32 | 0.70-2.49 | 0.387 |

| Other non-digital solitary activities | ||||||

| Practice meditation/mindfulness/praying | 1.33 | 0.80-2.22 | 0.271 | 1.26 | 0.40-3.93 | 0.693 |

| Writing/reading | 1.23 | 0.87-1.73 | 0.242 | 0.75 | 0.36-1.55 | 0.441 |

| Play an instrument/listen to music | 1.31 | 0.93-1.86 | 0.122 | 1.25 | 0.74-2.10 | 0.402 |

| Play board games, puzzles or crafting | 0.62 | 0.43-0.89 | 0.011 | 0.44 | 0.22-0.88 | 0.021 |

| Self-care strategies | ||||||

| Try to improve nocturnal rest | 1.08 | 0.74-1.58 | 0.676 | 0.96 | 0.54-1.70 | 0.895 |

| Do exercise | 1.33 | 0.94-1.88 | 0.107 | 0.74 | 0.45-1.20 | 0.223 |

| Eat more healthily | 1.01 | 0.69-1.47 | 0.964 | 0.90 | 0.51-1.61 | 0.731 |

| Unhealthy activities | ||||||

| Eat less healthily | 1.26 | 0.84-1.91 | 0.268 | 1.20 | 0.65-2.24 | 0.557 |

| Drink alcohol and/or take drugs | 2.61 | 1.41-4.81 | 0.002 | 1.56 | 0.79-3.11 | 0.203 |

| Smoke | 1.70 | 0.98-2.94 | 0.058 | 2.45 | 1.03-5.84 | 0.043 |

| Other strategies | ||||||

| Take vitamins or herbal remedies for immune system | 1.02 | 0.54-1.90 | 0.958 | 0.70 | 1.55-3.20 | 0.649 |

| Speak with mental health professionals | 3.43 | 1.82-6.46 | <0.001 | 4.56 | 1.31-15.9 | 0.017 |

| Spend time in private outdoor areas | 0.90 | 0.59-1.37 | 0.611 | 0.74 | 0.33-1.63 | 0.451 |

| Follow a daily routine of activities | 0.86 | 0.59-1.24 | 0.419 | 1.03 | 0.61-1.75 | 0.911 |

aOR: odds ratio adjusted by house size and type of educational centre according to complexity; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

Playing board games, puzzles or crafting also showed a protective effect in relation to worsening of mental health among both girls and boys, respectively (OR: 0.62, 95%CI: 0.43-0.89 for girls and OR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.22-0.88 for boys). Playing videogames also showed a protective effect in relation to worsening of mental health among girls (OR: 0.66, 95%CI: 0.45-0.97).

Among girls, other strategies related to unhealthy habits, like consumption of alcohol or drugs, were associated with a higher probability of declaring worsening of mental health due to the pandemic (OR: 2.61, 95%CI: 1.41-4.81). An association between smoking and a higher probability of declaring worsening of mental health due to the pandemic was seen among boys (OR: 2.45, 95%CI: 1.03-5.84).

Finally, adolescents who had spoken to mental health professionals reported a higher proportion of worsening of mental health (OR: 3.43, 95%CI: 1.82-6.46 for girls and OR: 4.56, 95%CI: 1.31-15.9 for boys) (Table 5).

DiscussionThis study demonstrated the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being in adolescents and a clearly worse impact on girls. The use of social and digital media to keep in contact with friends and reduce social isolation was the most commonly reported coping strategy for both girls and boys, whereas gender differences were seen in the use of other strategies used such as the higher proportion of girls using social activities related to family and/or friends in comparison to boys. This study also shows an association between coping strategies and self-perceived mental health status in adolescents in Catalonia. In this sense, the use of unhealthy habits during the early pandemic period (e.g., substance use) was associated with a higher probability of declaring worsening mental health among both girls and boys, whereas the use of other positive coping strategies (e.g., spending time with family) was associated with less adverse mental health among girls.

The higher percentage of girls than boys that perceived a worsening of mental health due to the pandemic and the higher level of stress caused by general uncertainty it produced is consistent with others studies studies.4–10 Emerging evidence indicates that girls perceive the impact of COVID-19 on their psychological well-being differently from boys.24 However, a higher prevalence of diagnoses of anxiety since the start of the pandemic observed in the study (8.7% girls and 2.4% boys) suggests that objective data exists to confirm the worsening of mental well-being in girls. All adolescents experienced more intense emotions than usual linked to the pandemic such as: worry, boredom, frustration, and disappointment, with girls presenting higher mean scores on most of the emotions that negatively affected psychological well-being. Other studies with children and adolescents in Spain during the first months of the pandemic revealed feelings like fear, sadness and boredom, typical of the break with routine and loss of predictability the pandemic supposed.7 Although no difference was observed in type of concerns most reported according to gender, there were differences in intensity with girls showing the highest prevalence, as reported previously.25 The fact that family or friends could die if infected by SARS-CoV-2 was the commonest concern reported for both genders; a risk factor for poorer psychological well-being in young people observed in several studies.26 The second major stressor was fear of losing work, both for themselves and/or family members, consistent with a previous study in Catalonia where a decline in family income was associated with poorer overall well-being for girls and boys.27

Amongst the most common strategies found in our study to cope with the pandemic, for both girls and boys, were maintaining contact with friends online or through social media, together with other solitary digital activities. Although that coping strategies alleviate the effects of social distancing, social network use has also been associated with negative psychological consequences in this context.28

Girls reported in a higher proportion than boys the use of social activities related to family and/or friends as a coping strategy, as observed previously. In addition, among girls, spending time with family members was associated with less likelihood of declaring worsening mental health due to the pandemic.29 Other studies also show that better communication and emotional support from family members during the pandemic was a protection against developing symptoms of anxiety or depression in children and adolescents.30

As in other studies31 a large percentage of adolescents referred to self-care strategies like exercise to deal with the pandemic, which has shown mental health benefits for the young. However, other less healthy habits like smoking, and consumption of alcohol and/or drugs, were also used as coping strategies.17 Compared to boys, more girls in our sample reported engaging in tobacco use to cope with the pandemic. This finding is consistent with evidence that girls may be more likely to use substances as a coping strategy and responds to their learning and development, as well as their mental health and psychosocial well-being needs.32 Worry and fear due to COVID-19, together with consumption to relieve feelings of emotional discomfort caused by anxiety, stress or depressive feelings, have been identified as factors associated with coping strategies involving substance use.33

Finally, seeking professional help as a coping strategy was reported by a few number of adolescents, and more in girls, in line with previous studies showing young people will more often disclose their feelings to parents and friends than to professionals, this is in part due to mental health stigma and embarrassment, a lack of mental health knowledge and negative perceptions of help-seeking.34

Some limitations of this study include a lack of pre-pandemic data to confirm a real decrease in mental health in adolescents using internationally validated scales. However, the questionnaire used was created specifically to measure perception of impact of the pandemic on psychological well-being in adolescents and was never intended to diagnose the real state of mental health of participants. On the other hand, as it is a transversal study, we cannot establish causality between worsening mental health and coping strategies adopted. Additionally, we cannot rule out a significant degree of memory bias, as in any retrospective survey. Finally, considering the non-probabilistic sampling method, the results cannot be generalized to the school population of Catalonia. However, one of the most important strengths of this study was the formation of a network of schools that worked together to develop, adapt and implement health protocols, studies and scientific dissemination in the face of the pandemic, providing safe attendance of face-to-face activities for students and education professionals. Still, in relation to the methodology, the study design, carried out concomitantly with the participatory research model, revealed a strengthening of science teaching and the strengthened student involvement, seeking to mitigate as much as possible the impact of the pandemic on their mental health.

In conclusion, this study presents evidence on the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological well-being in adolescents in schools in Catalonia, especially in girls. Although the generalized use of social media technology as a coping strategy stands out, other activities and strategies have been employed, and differently by boys and girls. Some of these strategies have been related to better psychological well-being, but we must not forget that unhealthy strategies, such as consumption of alcohol and/or drugs and smoking, have also increased to deal with difficult situations. Due to the pandemic adolescents experienced much stronger negative emotions than usual such as worry, irritability or frustration; with girls presenting a higher proportion of them. More focus must be put on feelings generating emotional discomfort, especially if they are very intense and prolonged, because the absence of adequate tools to manage them can put those who experience them at risk. It is important to keep monitoring the medium- and long-term secondary impacts of the pandemic on mental health outcomes and consequent coping behaviours, especially considering gender perspective.

Finally, access for adolescents to emotional support services must be improved, both within schools and in specialized mental health centres, taking into account the need to support young people as they develop the necessary positive coping strategies required during health crises such as that of COVID-19.

Availability of databases and material for replicationAll anonymized databases and their corresponding codebooks are available in the public repository https://github.com/Escoles-Sentinella/Impact-on-psychological-wellbeing. Due to legal restrictions in relation to the “Personal Information Protection Act”, personal or spatial data that allow identified any participant, including the name of the school, which was used as an adjustment factor in the analysis, cannot be made publicly available. Requests for complementary data can be sent as a formal proposal to the CEEISCAT via email ceeiscat@iconcologia.net.

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the psychological well-being of adolescents who experienced high levels of stress and anxiety. In order to deal with the pandemic, adolescents used several coping strategies, such as physical activity and/or use of social networks to maintain contact with peers, among others.

What does this study add to the literature?The study highlights gender differences in how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected adolescent mental wellbeing, and, for the first time in Spain, demonstrates a relationship between coping strategies used and self-perceived impact of COVID-19 on mental health by gender.

What are the implications of the results?Findings highlights the need to monitor adolescent's mental health in schools considering a gender perspective. Support services for the development of healthy coping strategies during health crises like COVID-19 should be made.

María del Mar García-Calvente.

Transparency declarationThe corresponding author on behalf of the other authors guarantee the accuracy, transparency and honesty of the data and information contained in the study, that no relevant information has been omitted and that all discrepancies between authors have been adequately resolved and described.

Authorship contributionsC. Folch, A. Colom-Cadena and J. Casabona made substantial contributions in the study conception and design. F. Ganem, I. Martínez and C. Cabezas made substantial contributions in data gathering, data analysis and interpretation. C. Folch wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions in critical review with significant intellectual contributions. All authors approved the final version for publication.

The authors would like to thank the Health Department and Department of Education of the Government of the Catalonia (Spain), the former Direcció General de Recerca i Innovació en Salut (DGRIS) and Institut Català de la Salut (ICS) that made this project possible, and all the health care professionals acting as a COVID-19 pandemic health taskforce in Catalonia. Also, we would like to specially thank the effort and dedication all the sentinel schools’ staff, students and families who participated in the project.